Introduction

Colorectal dehiscence affects almost 14% of patients undergoing anterior resection for rectal cancer, and the complication proves fatal in 7% of them [1, 2]. Bowel leakage is a result of dehiscence with subsequent diffuse peritonitis or pelvic abscess, which requires reoperation in 50% of all patients undergoing rectal resection [1].

Dehiscence on the one hand is a life-threatening complication, which extends hospital stay and increases the costs of treatment, whereas on the other hand it is an independent prognostic factor decreasing the overall as well as the cancer-specific survival rate [3]. Diverting colo- or ileostomy with drainage of the surgical site infection and, in extremely difficult conditions, disassembling of the ineffective anastomosis are currently available solutions [4, 5]. The choice of treatment depends on the patient’s general condition, localization and size of the defect.

Anastomotic leakage was classified into three grades by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer to make that choice easier and clearer. Thus, the postoperative course is not affected by grade A leakage, whereas grade C is an absolute indication for surgery. Grade B in turn calls for active intervention in the form of minimally invasive procedures including endoscopic procedures, e.g. endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT) [6]. That procedure is used primarily for patients with partial dehiscence in whom protective stomy as a complement to anterior rectal resection was performed [1, 7]. Drainage of the bowel leakage and/or pelvic abscesses and protection against further contamination of the peri-rectal space are the major ways of action of EVT [7, 8]. There are other endoscopic methods currently available for treatment of dehiscence such as hemostatic clips, stents, tissue adhesives, or local application of cellular growth stimulants, and laser pulses [9–12].

However, standard management for dehiscence of colorectal anastomosis has not yet been established [1].

Aim

The aim of the article was to present the management with minimally invasive and endoscopic procedures with an overview of the significance of the size, localization and duration of the leakage.

Material and methods

Medical records of 25 patients with dehiscence of colorectal anastomosis treated with minimally invasive and endoscopic procedures between 2015 and 2020 were retrospectively evaluated for the study. The investigated group consisted of 17 males and 8 females aged 24 to 79. Anterior resection for rectal cancer was performed in 16 patients, with prior neoadjuvant radiotherapy in 11 of them. Open surgery procedures were completed in 15 patients, and laparoscopy in 10. Protective stomy as a complement to colorectal resection was constructed in 17 cases. A group of 15 patients with leakage was admitted from other county hospitals with the resulting median treatment delay of 12 days (Table I).

Table I

Noninvasive approach depending on the size of the leak

| Leak or fistula < 7 mm | Leak or fistula > 7 mm |

|---|---|

| Hemostatic clips, tissue adhesives, cellular growth stimulants | Endoluminal vacuum therapy (EVT) |

| Intraluminal EVT: technical problems, leak or fistula < 7 mm | |

All the symptomatic patients were examined with endoscopic measures within 3–5 days after surgery with the exception of the patients from other hospitals, who were examined on admission. Gastrofiberoscopes and carbon dioxide insufflation were provided for the examination. The diameter of the dehiscence was assessed either as a circular segment assuming fractional values, e.g. 1/4 to 1/2 of the circumference of the circle, or with open biopsy forceps measuring 5 mm in exceptional cases. Additional studies such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and laboratory tests indicating systemic inflammation were used for detection of septic complications, e.g. abscess, gangrene, or for monitoring the therapy.

Minimally invasive procedures were applied for dehiscence not exceeding half the circumference of the circle with no extensive septic complications requiring urgent relaparotomy. In the case of larger dehiscence the application of endoscopic treatment depended on the local as well as the general condition of a patient. Routinely, a handmade EVT dressing consisting of a catheter wrapped with polyurethane open-pored foam was introduced into the defect. Due to the limited effectiveness of drainage, fistulas smaller than 7 mm were not suitable for treatment with direct EVT. In these situations or in the case of technical problems an intraluminal EVT was inserted as an alternative. At the beginning of the treatment, usually within 3–4 days, during which the dressing was changed twice, a stable negative pressure of 100–120 mm Hg was maintained. Afterwards, at the time of the last dressing change, the pressure was reduced to the value of 50–70 mm Hg, and the dressing was left intact for 4–5 days. In order to fully heal persistent narrow (1–3 mm) leaks, an attempt was made to close them with hemostatic clips, fibrin sealant (Tisseal, Baxter AG, Vienna, Austria), or platelet rich plasma (Xerthra PRP Kit, Biovico, Poland) with the possibility to increase the number of applications if it was clinically justified (Table II).

Table II

Patient characteristics and history of previous treatment

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Age* | 51 years (24–79) |

| Sex | Female: 8 Men: 17 |

| Type of procedure | Laparotomy: 15 Laparoscopy: 10 |

| Indication for surgery | Colorectal cancer: 16 Diverticulosis: 6 IPAA (colitis ulcerosa): 3 |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 11 patients |

| Size of dehiscence | < 1/4 of circuit: 12 1/4–1/2 of circuit: 13 |

Results

The time of diagnosis of the dehiscence ranged from 4 to 17 days with average time of 8 days. The diagnosis was delayed in the group of patients with protective stomy, and those admitted to the clinic from other hospitals. In addition, the leakage occurred following protective ileostomy closure in 3 patients within 3–6 months after anterior resection of the rectum. The average time of active leakage between the diagnosis and the endoscopic treatment was 5 days, with the range of 1–7 days.

The treatment was successful in 23 patients with leakage limitation and evacuation of abscesses. The size of a defect was reduced by at least one third after changing the dressing on average 5 times, ranging from 3 to 8.

Finally, the defect was completely healed with EVT in 14 patients, whereas it was partially closed to a narrow orifice with a diameter less than 4 mm in 9 patients. Next, the smallest orifices were treated with tissue adhesives, platelet rich plasma, or hemostatic clips. As a result, the dehiscence was healed in the next group of 7 patients, whereas it was limited to a slit sinus in another 2 patients. Ultimately, continuity of the digestive tract was restored in 12 patients and another 6 are waiting for surgery. In 5 cases, eligibility for continuity restoration was suspended due to strictured colorectal anastomosis treated with endoscopic balloon dilatation. Total treatment time involving both EVT and other endoscopic methods of therapy ranged between 12 and 85 days. Abdomino-perineal resection of the rectum was performed in 1 case due to recurrent perirectal abscesses. For the same reasons, another patient underwent Hartmann’s resection with conversion of loop ileostomy to terminal colostomy.

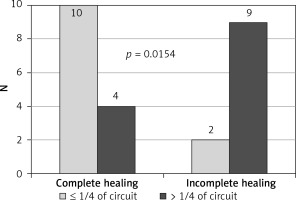

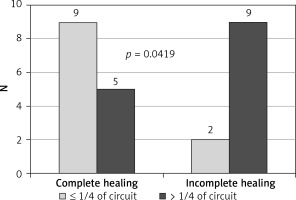

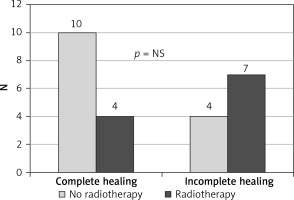

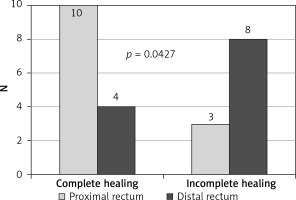

The study showed that the endoscopic treatment attempted within 7 days from leakage formation, as well as the size of the dehiscence less than 1/4 of the circumference of the circle, were factors influencing healing preferably (Figures 1, 2). In contrast, ultra low resection and neoadjuvant radiotherapy impaired the healing process, limiting the effectiveness of minimally invasive techniques, especially EVT (Figures 3, 4).

Discussion

Diverting colo- or ileostomy with drainage of the surgical site infection is currently a commonly used method of treatment of colorectal anastomosis dehiscence [13]. However, patients with circumscribed leakage with no organ failure are candidates for treatment with minimally invasive procedures, primarily EVT. The use of these methods is always determined by the patient’s general condition and technical possibilities related to the degree of anastomotic destruction [14, 15]. The time between appearance of the dehiscence and beginning of treatment can also largely determine its effectiveness [16]. Prolonged leakage is responsible for septic complications of the dehiscence in the form of perirectal abscess with the following, possible chronic phase of the infection such as sinus or fistula [17]. Anastomosis dehiscence is defined as separation of sutures within 30 postoperative days [18].

In most cases, the symptoms of leakage appear a few days after the procedure. However, some studies indicate that anastomotic dehiscence may occur later; therefore endoscopic assessment performed even between the 7th and 10th day after surgery may not show any abnormalities [19]. Another challenge is presented by asymptomatic patients without or with mild clinical markers of anastomotic failure. One of the factors determining the absence of morbid signs is a protective stoma, so patients with low rectal tumors, higher staging and after chemoradiotherapy are vulnerable to insufficient diagnosis and prolonged treatment [19–21]. Therefore, some authors suggest the term “delayed leakage” when dehiscence is diagnosed after hospital discharge or more than 30 days after surgery [22].

Endoscopy is crucial for the diagnosis and treatment of complications of rectal surgery. The examination protocol should indicate the size of the dehiscence, its relation to the anus, and the depth of the concurrent sinus or abscess, and describe other pathologies such as ulcerations, ischemic foci, or inflammatory polyps [19]. The dimensions of the lesion may be difficult to define; therefore the defect is most often presented as a part of the anastomotic circumference or, alternatively, other objective criteria can be used to describe the lesion, such as endoscope diameter or biopsy forceps. A comparison of the above parameters in a larger group of patients allows one to create a universal classification crucial for treatment and follow-up [19, 21].

Time to start the endoscopic treatment is crucial for effectiveness of the therapy. There are studies which show that the rate of dehiscence closure reaches 75% if EVT was applied up to 6 weeks after resection [8, 23]. Although the history of negative pressure wound therapy goes back to the early 1990s, application of the method for the treatment of anastomosis dehiscence appeared in the mid 2000s [24, 25]. EVT may be applied for dehiscence of various localizations regardless of the size in certain cases. The endoscopic method is more effective compared to stents. After installation of the former, the defect within the anastomosis is not blocked; also, outflow of discharge, migration and iatrogenic perforation are avoided, which may happen after introduction of the latter [26, 27]. EVT is not only a kind of continuous drainage but it also reduces inflammatory edema, increases blood flow, shrinks the defect, and finally it accelerates formation of fresh granulation tissue with subsequent closure of the dehiscence. Stents used in other gastrointestinal leaks are of less use in these cases [28, 29].

However, in some cases, complete healing of the defect is less likely even with extended EVT. As a continuation of the therapy other minimally invasive methods are applied such as hemostatic clips, tissue adhesives, or local application of cellular growth stimulants [16, 30]. Mainly chronic dehiscence in the form of a sinus or fistula, and the defect after radiotherapy appear refractory to treatment with endoscopic measures [16, 31]. Proper healing of the aforementioned chronic dehiscence is prevented by fibrosis within the affected tissues in connection with poor shrinkage, among other possible factors. This relationship is supported by the experience obtained in the treatment of recurrent anal fistulas [32]. Therefore, tissue remodeling with the use of cellular growth factors may be beneficial in the treatment of persistent anastomotic leak. The local supply of PRP reflects the natural healing process and leads to the production of granulation tissue and a network of blood vessels. The authors’ experience in the healing of leaks by endoscopic application of autogenous PRP and platelet rich fibrin (PRF) is optimistic, the more so as the method produced satisfactory results in the treatment of recurrent anal fistulas [29, 33].

The present results suggest that EVT is most effective for the treatment of defects with a diameter greater than 7 mm. It is due to the limitation of the minimal diameter of a catheter as well as foam compression limitations [34]. Hemostatic clips, tissue adhesives, and cellular growth stimulant are in turn most suitable for the healing of a small, persistent fissure such as a perirectal sinus remaining after EVT treatment [35, 36]. An intra-luminal EVT inserted at the level of the anastomosis is the only solution either in the case of a dehiscence smaller than the diameter of a catheter, i.e. 7 mm, or if the longitudinal axis of a defect is located perpendicularly to the line of sutures [16, 35]. That way of EVT application is also recommended for primary prophylaxis of the dehiscence after high risk, ultra low anterior resections [37].

The functional efficiency of a complicated anastomosis after minimally invasive treatment is also an important issue. There is no doubt that an early detected and controlled leak enables effective passage of the intestinal contents without secondary disturbances at the anastomotic site [38]. Delayed and prolonged endoscopic treatment of an extensive dehiscence result in poor function of an anastomosis due to fibrosis of the adjacent tissue [7, 16]. The stricture, in most cases, is refractory to the endoscopic balloon dilatation, while stenting or resection of the anastomosis is usually impossible or risky for anatomical reasons [5, 27, 39].

Our experiences show that in the case of low rectal ruptures, especially those preceded by radiotherapy, the inflammatory reaction affects not only the anastomotic area but also adjacent tissues. The stiff scar formed as a result of healing narrows the rectal stump and the anal canal and limits the efficiency of the sphincters. Therefore, Hartmann’s resection of the defunctioning colorectal anastomosis with terminal colostomy and abdomino-perineal resection are the only available methods [40, 41].

Conclusions

The presented results of treatment of colorectal anastomosis with endoscopic methods are encouraging. Time to diagnose and start the endoscopic treatment of the colorectal anastomosis dehiscence is crucial for effectiveness of the therapy due to shortened exposure of the tissues to bowel content with proper healing and a smaller scar. Endoscopic methods are indicated for patients with the dehiscence identified up to 7 days after surgery, located in the upper or middle part of the rectum, with small defects not exceeding 1/4 of the circumference of the circle. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the late functional results of anastomosis dehiscence treated with endoscopic methods.