BACKGROUND

Everyone is fallible. This is an undeniable fact – an existential truth about being a human. As representatives of the most intelligent species, humans perceive the world, try to understand the external and internal reality, and construct theories about the world and themselves. However, even the smartest animal, as the homo sapiens is considered to be, makes mistakes in its reasoning and may be wrong about its own beliefs and theories. Yet, people differ in how willing they are to admit that their knowledge is limited. In fact, from the evolutionary perspective, being arrogant and overestimating the credibility of one’s own beliefs is assumed to be a natural inclination (Gregg & Mahadevan, 2014; Tangney, 2000). This phenomenon, captured as a dimension ranging from intellectual arrogance to recognising the limitations of own knowledge, has been recently conceptualised as intellectual humility (IH). Intellectually humble people are “those who are more concerned with getting at the truth than promoting themselves or protecting their own ideas” (Barrett, 2017, p. 1).

Intellectual humility seems to be a highly desirable trait. Intellectually humble politicians, journalists, religious leaders, teachers and scientists, as well as managers, parents, spouses and even friends, may help in dealing with current problems of social life (see e.g., “the social functioning” and “the societal peace” hypotheses by Worthington et al., 2017). This refers to academia as well, where the prototypical scientist is someone who enjoys and continuously looks for a “hole in the whole”, who perceives their individual development as a delve into what undermines their knowledge, and who tries to rethink problems. The other side of the coin is how much people are affected by the need to protect their ego and maintain – sometimes at all costs – high self-esteem.

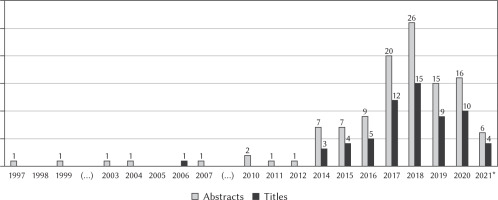

Given the importance of this topic, one may be surprised that it is only in the last few years that IH has become a subject of scientific psychology. The APA PsycInfo search (2021.05.08) showed that until 2014, the term “intellectual humility” was almost absent in the titles of journal papers and only occasionally appeared in their abstracts (see Figure 1). In the last six to seven years, the number of papers focused on IH has been growing, and they are published in influential mainstream psychology journals such as Personality and Individual Differences, Self and Identity, Journal of Research in Personality, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology and Journal of Personality, to name just a few. Still, the total number of papers devoted to IH is not very high, especially when compared to other relatively new constructs. As an example, we compared the APA PsycInfo searches for intellectual humility and self-compassion (Neff, 2003). When the key concept was entered in the title search, we found 67 records for intellectual humility and 1,221 for self-compassion. Abstract searches resulted in 118 and 2,129 records, respectively. Thus, intellectual humility seems to be an understudied issue, and much empirical work is yet to be done. The present paper aims to introduce the topic of intellectual humility to the broader public as well as to review and comment on the existing literature.

INTELLECTUAL HUMILITY AS A VIRTUE IN THE PHILOSOPHICAL APPROACH

Before the results of recent psychological research on intellectual humility are presented, it may be inspiring to take a look at other types of discourse in which the phenomenon of being intellectually humble is emphasised. In history, Socrates was the ideal example of a thinker who embodied intellectual humility. When the Oracle of Delphi named him as the wisest of men, for a long time he could not believe in such a judgment (Plato, ca. 399 B.C.E./2005). The problems that Socrates was particularly interested in concerned values such as the meaning of goodness, beauty, truth or justice. Socrates was convinced that he himself did not know what the values were, yet it was essential to find out. He also decided to show the Oracle that she was wrong about him and that he was not the wisest. To this purpose, he decided to ask those who were considered particularly wise or who seemed especially intelligent to him about the subject of values. When the interlocutor replied that he knew what the values were, Socrates asked further questions, and in every case, ultimately discouraged, he had to admit that he did not find a person wiser than himself. This confused him deeply because he did not consider himself wise, either. But, in the words of Plato (ca. 399 B.C.E./2005, p. 83), Socrates came to the conclusion, from his research, that “I am wiser than this man; for neither of us really knows anything fine and good, but this man thinks he knows something when he does not, whereas I, as I do not know anything, do not think I do either. I seem, then, in just this little thing, to be wiser than this man at any rate, as what I do not know I do not think I know either”.

From this originated the famous Socratic “I know that I know nothing”, a symbolic, model expression of an attitude revealing intellectual humility, contrasted with the arrogance of those “who know” when it turns out only that “they seem to know”.

In the history of philosophy, we can find many thinkers who have taken a particular interest in the limitations of human knowledge and have themselves presented an attitude of genuine humility towards their own knowledge. Based on epistemology, we would say that we are discussing the ability to recognise the limits of cognition and identify the range of agnosticism or scepticism. Regarding the ability to know about the world and the essence of things, those who perfectly understood the imperfections of their own knowledge included, for instance, Hume (Hume & Millican, 2007) and Kant (Langton, 1998).

It can be said that over the centuries, the perception of intellectual humility has established itself in two dimensions of the philosophical tradition. First, it is a virtue that defines an ideal scholar and a teacher, who not only likes to pass on knowledge but is also willing to question what they know and is open to reviewing their own views. In this case, the ethical dimension of intellectual humility is considered, treating IH as a specific attitude (Roberts & Wood, 2003; Tanesini, 2016). The second aspect of intellectual humility reveals itself in the approach to cognition and expresses an epistemological, or meta-epistemological, rather than an ethical standpoint. This stance would be associated with a particular sensitivity to the purity and clarity of reasoning, its logical correctness and the ability to recognise the limitations of knowledge resulting from an individual’s insufficient cognitive skills or competence (Whitcomb et al., 2015).

Thomas Kuhn (1962/1996) described perfectly how these two aspects were connected, following the development of scientific theories and the revolution in the way of thinking. In the examples he analysed, one of the factors that often impeded progress was the lack of intellectual humility in great scientists. This feature was particularly distinctive for those who broke the paradigm and carried out the revolution.

THE PHENOMENON OF INTELLECTUAL HUMILITY IN HUMANISTIC PSYCHOLOGY

Even if, as mentioned before, the term “intellectual humility” is relatively new in empirical psychological studies, the topic of a humble approach to one’s own knowledge is not a new issue in terms of psychology itself. A certain type of attitude characteristic for a person who desires knowledge and thus does not close oneself to information and is not easily prone to ready answers has been considered in classical personality theories. This issue was mostly present in inquiries of humanistic psychologists such as Maslow, Rogers or Allport.

A good example of this humanistic approach is Maslow’s (1954/1970) theory, as expressed in his famous book Motivation and personality. But before the results of Maslow’s research became known, considerations about some kind of humility appeared in Allport’s (1950) works. Intellectual humility that characterises the mature personality, according to Allport, is a sense of uncertainty in relation to the knowledge that one possesses. Allport developed this topic by analysing mature religiousness, where he concluded that, paradoxically, the agnostic attitude might be an important and essential part of maturity. In contrast, dogmatism can be seen in this context as a kind of arrogance of certainty.

Some traces of intellectual humility can also be found in Rogers’ (1959) famous postulate that it is the client who is a specialist, or an expert, in terms of his or her case. A psychologist, as an expert having general knowledge about the functioning of a human being, has no superiority in relation to knowledge about a particular individual’s life. In other words, this professional does not have a monopoly on the truth. It seems that the awareness of such a status of a psychotherapist or a counsellor should be considered as a crucial element for the development of an intellectually humble attitude, even regarding the so-called specialist knowledge.

The phenomenon of intellectual humility is, however, most fully present in Maslow’s (1954/1970) thought. In his theory of self-actualisation, Maslow had been searching for the distinctive features of self-actualising individuals. Although he did not explicitly point to intellectual humility, Maslow described this phenomenon as a part of “the democratic character structure”. In the description of this feature, he emphasised a general openness and kindness to otherness and to diversity among people, which can be found in the self-actualisers. This is clearly expressed in the following passage from Motivation and personality:

For instance they [subjects of Maslow’s study] find it possible to learn from anybody who has something to teach them – no matter what other characteristics he may have. In such a learning relationship they do not try to maintain any outward dignity or maintain status or age prestige or the like. It should even be said that my subjects share a quality that could be called humility of a certain type. They are all quite well aware of how little they know in comparison with what could be known and what is known by others. Because of this it is possible for them without pose to be honestly respectful and even humble before people who can teach them something that they do not know or who have a skill they do not possess. They give this honest respect to a carpenter who is a good carpenter; or for that matter to anybody who is a master of his own tools or his own craft (Maslow, 1954/1970, p. 168).

Therefore, intellectual humility seems to be a part of one of the more essential qualities that allow the identification of self-actualisation, alongside properties such as a more efficient perception of reality, acceptance (self, others, nature), spontaneity, autonomy, having peak experiences and more. It can be said that it gives nobility and underlines the specific maturity of self-actualising individuals’ personality. If one would search Maslow’s theory for a description of attitudes worth following, humility in terms of respect for other people’s knowledge is clearly honoured here. Contemporary research findings seem to support Maslow’s intuition on intellectual humility, identifying this attribute as something, first of all, desirable, associated with greater but not narcissistic confidence, healthier self-esteem and above all, an attitude of general openness to others and to diverse experiences.

The definitions that are used to operationalise intellectual humility in contemporary empirical research are consistent both with the ethical attitude outlined in philosophy and with those identified by humanistic psychologists as one of the expressions or one of the characteristics of a mature, self-actual-ising personality.

CONTEMPORARY UNDERSTANDING OF INTELLECTUAL HUMILITY IN EMPIRICAL PSYCHOLOGY

There is no single, universally accepted psychological definition of intellectual humility. However, the awareness of potential frailty of one’s beliefs may be considered the core of this theoretical construct. The aspect of awareness was explicitly included at least in some definitions as, e.g., in Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse’s conceptualisation (2016, p. 210), which additionally specified it “as a nonthreatening awareness of one’s intellectual fallibility”. This was to emphasise that IH requires a relative lack of overinvolvement of one’s ego in one’s intellectual activities and their products, which “should result in openness to revising one’s viewpoints, lack of overconfidence about one’s knowledge, respect for the viewpoints of others, and lack of threat in the face of intellectual disagreements” (Krumrei-Mancuso & Rouse, 2016, p. 210). The awareness aspect of IH was also emphasised by Leary et al. (2017, p. 793), who defined IH as “recognising that a particular personal belief may be fallible, accompanied by an appropriate attentiveness to limitations in the evidentiary basis of that belief and to one’s own limitations in obtaining and evaluating relevant information”. The focus on limitations was also highlighted by Haggard et al. (2018, pp. 184–185), whose conceptualisation of IH “involves one’s intellectual limitations, which lies on a spectrum between intellectual arrogance and intellectual servility”. They identified three factors of IH, called (a) owning one’s intellectual limitations, (b) love of learning and (c) appropriate discomfort with one’s intellectual limitations, i.e., being attentive to but not preoccupied by one’s own limitations (Haggard et al., 2018).

All the above definitions share the intrapersonal aspect of IH with the focus on the perception and awareness of one’s intellectual limitations. As such, they represent the first of three types of definitions distinguished by Barrett (2017). The other two types emphasise the interpersonal and epistemic aspects, respectively. The interpersonal approach highlights that being intellectually humble entails a lack of overconcern about one’s social status related to one’s intellect and its products such as ideas, beliefs and knowledge (Roberts & Wood, 2003). The self-perceived social standing of highly intellectually humble individuals is relatively independent of the ongoing intellectual achievements and is not easily threatened by the possibility of being wrong.

The third type of definition adds an epistemic dimension to the conceptualisation of IH. This draws heavily on the philosophical tradition of epistemic virtues (see Church & Samuelson, 2017). IH can be defined here as a “virtuous middle between two vices, intellectual arrogance and intellectual diffidence” and “a tendency to accurately track whether or not one should hold certain beliefs to be knowledge: not overconfident in one’s beliefs, but also not holding them too loosely when one should hold them firmly” (Barrett, 2017, p. 1). A good example of such a philosophically rooted conceptualisation is Tanesini’s (2016, p. 399) definition of IH as a “cluster of attitudes … directed toward one’s cognitive make-up and its components, together with the cognitive and affective states that constitute their contents or bases, which serve knowledge and value-expressive functions”. Tanesini (2016) argues that IH is a complex virtue composed of two related but distinct dimensions of modesty and intellectual self-acceptance. Modesty is related to a positive stance to one’s epistemic success, which is praised for its epistemic value per se (such as getting closer to the truth) rather than for social status or self-esteem raised by being the agent of this success. The second dimension of IH, i.e., intellectual self-acceptance, is related to open-mindedness to one’s intellectual shortcomings and limitations, resulting in the ability to accept them and not being resentful of a fair criticism from others. This aspect of humility is “a focus on one’s own limitations which is not driven by a concern for how their presence reflects on one’s reputation or self-esteem” but rather “caring that one has limitations because of their effects on the pursuit of various epistemic goods such as truth and understanding, rather than for their potential impact on one’s reputation or one’s sense of self-esteem” (Tanesini, 2016, p. 405).

When defining IH, four additional issues should be raised. First, regardless of the different dimensions listed above, IH is basically a cognitive phenomenon in the sense that it pertains to what and how people think about themselves and their social world (Leary, 2017). This is why IH is characterised by Church and Barrett (2017) as “doxastic”, which means relating to beliefs. Second, although most definitions suggest the conceptualisation in terms of a relatively stable personality trait, this general dispositional aspect does not exhaust the concept of IH. Using Leary’s words (2017, p. 3), “there is no contradiction or conflict in viewing IH both as a state (how intellectually humble a person is in a particular situation at a particular time) and a trait (how intellectually humble a person is in general, across situations)”. The state aspect of IH refers to momentary, context-specific recognition of the fallibility of a particular belief or view. In contrast, the trait aspect of IH refers to individual differences in the disposition to recognise one’s potential cognitive fallibility across situations. This distinction is in line with the classical state-trait distinction as applied to many personality constructs (Cattell & Scheier, 1960; Nezlek, 2007; Steyer et al., 2015). Third, similarly to other personality variables, especially cognitive ones, IH can be conceptualised in terms of both general, context-free cognitions and specific beliefs. The former is implicitly suggested by most of the above definitions. The latter was explicitly proposed by Hoyle et al. (2016). Drawing on Leary et al.’s definition (2017) of general IH (as cited above), they defined specific intellectual humility as “the recognition that a particular personal view may be fallible, accompanied by an appropriate attentiveness to limitations in the evidentiary basis of that view and to one’s own limitations in obtaining and evaluating information relevant to it” (Hoyle et al., 2016, p. 165). In contrast to general, context-free IH, specific IH refers to one’s beliefs referring to a relatively broad domain (e.g., politics, religion or health) as well as lower-level specificity of one’s views relating to a topic within a domain (e.g., government surveillance as a topic within the political domain) or even issues within a topic (e.g., tracking of phone records as an issue within the topic of government surveillance; see Hoyle et al., 2016, p. 166).

Fourth, to sum up the definitional considerations, intellectual humility should be placed in the broader context of general humility. According to Davis et al. (2016), who advocate distinguishing the two constructs, general humility involves two related aspects: “(a) an accurate view of one’s strengths and weaknesses (including acknowledging one’s limitations) and (b) an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented rather than self-focused, marked by the ability to restrain egotism (i.e., self-oriented emotions such as pride or shame)” (Davis et al., 2016, p. 215). Intellectual humility is conceptualised as a subdomain of general humility and thus shares its two basic aspects by applying them to the domain of intellect and its products, such as one’s knowledge, views and beliefs. Consequently, IH involves “(a) having an accurate view of one’s intellectual strengths and limitations and (b) the ability to negotiate ideas in a fair and inoffensive manner” (Davis et al., 2016, p. 215).

RESEARCH ON INTELLECTUAL HUMILITY

Having discussed basic definitions of IH in contemporary psychology, we shall review selected results of empirical studies that employed those conceptualisations. To give an idea of the breadth of IH-related empirical explorations, we shall focus on four strands of research that address the issues of personality traits, cognitive functioning, social relations, and religiosity.

PERSONALITY TRAITS

Among various approaches to defining IH, those closest to personality psychology suggest that IH is a relatively stable disposition that identifies the differences between individuals. It is thus essential to look at the relationships between IH and other stable personality dispositions. The researchers who compare IH with different personality traits consider them, on the one hand, as a point of reference and, on the other hand, as domains that make it possible to distinguish IH as an independent phenomenon.

Certain elements of IH’s semantic meaning are found to be similar to various characteristics of the traits from the five-factor model of personality (Costa et al., 1991; Costa & McCrae, 1992). The most obvious is the conceptual relationship between IH and openness to experience. However, Church and Samuelson (2017, p. 163) reasonably stress being careful with excessive simplification:

Despite these helpful leads in the personality literature, it seems important to avoid an oversimplified association of intellectual humility with certain personality traits. Even traits that seem to track with intellectual humility could have their own special hazards. For example, a trait like Openness could easily be an impediment to intellectual virtue if it leads to a kind of non-committal intellectual paralysis.

In fact, the research carried out in recent years has made it much clearer and allowed IH to be placed in the trait theory context.

Intellectual humility has been compared with personality traits, mainly during the development and validation of new measures of IH. In Porter and Schumann’s (2018) research, the general score of IH, understood as being aware of the limitations of one’s own knowledge and the ability to appreciate others’ intellectual strengths, was compared with the Big Five in two independent studies. In the first one, IH showed weak, though statistically significant, relationships with agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness to experience and emotional stability but no significant relationship with extraversion. In the second study, the effects were generally replicated, with similar strengths of correlations, but in this case, also the relationship with extraversion was significant (though very weak). In research by McElroy et al. (2014), where IH was again measured as a general feature, positive and high correlations with agreeableness, openness to experience, and conscientiousness, and also a high but negative correlation with neuroticism were found. In Leary et al.’s study (2017), significant but weak relationships were found only in the case of agreeableness and openness. To allow a finer description of those relatively small effects, the authors decided to draw out from the NEO-PI-R those subscales that seem to be closest to IH. As predicted, IH clearly correlated with the ideas, values and actions facets of openness to experience.

Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse (2016) focused only on openness to experience and found a moderate relationship between openness and IH (r = .40). IH also proved to be a significant independent predictor of openness to experience. After including social desirability and individualism in the model, IH explained 15% of the variance of openness. Haggard et al. (2018) combined three measures of IH in one study, which allowed for a comparison between different operation-alisations of the focal construct. When IH was defined in terms of a limitation-owning perspective (Haggard et al., 2018), it correlated with all five basic traits. The highest correlations were found between IH and conscientiousness (r = .49) and neuroticism (r = −.49). For a more general operationalisation of IH as “the degree to which people recognise that their beliefs might be wrong” (Leary et al., 2017, p. 1), the relationships between IH and personality traits were weaker and concerned only openness, conscientiousness and agreeableness (Haggard et al., 2018). Finally, when IH was defined as “a nonthreatening awareness of one’s intellectual fallibility” (Krumrei-Mancuso & Rouse, 2016, p. 210) and measured accordingly, the relationships with personality traits were identified only in the case of conscientiousness, agreeableness and neuroticism. The strength of those relationships was also lower compared to the measure employing the limitation-owning perspective (Haggard et al., 2018).

To summarise, for every study that compared IH with the Big Five traits, clear relationships with at least one trait were observed. Most often, it was agreeableness, which may be regarded as theoretically less obvious and thus clearly emphasises the importance of the social dimension of IH. This is followed by the relationships with openness to experience and conscientiousness, which in turn are closer to the epistemic aspect of IH. The relationship between IH and extraversion was the least frequently observed. At the same time, it should be emphasised that the strength of the relationships between personality traits and IH was usually not very high, which points to the need of distinguishing intellectual humility as an independent construct. Still, future research should address the issue of diversity of the Big Five measures and resulting potential differences with regard to relationships between personality traits and IH.

COGNITIVE FUNCTIONING

The definitions of IH clearly indicate that the first core aspect of IH – the awareness of one’s intellectual limitations – concerns cognitive processes. Thus, it is reasonable to inquire whether and how IH relates to intelligence, cognitive styles, decisions and judgement-making.

As for intelligence, Danovitch et al. (2019) observed that IQ level correlates with indicators of IH. This study’s procedure contained a quiz-game, which showed an intriguing effect – the higher the participants’ IQ was, the more frequently they asked for help and reported lower confidence in their own answers. Another study confirmed this effect and showed a significant interaction of IQ and cognitive flexibility. The highest scores of IH were observed when either IQ level or flexibility was high (Zmigrod et al., 2019). What is more, the perceived intelligence of a discussion partner positively predicted participants’ cognitive openness, which was strongly associated with IH (Jarvinen & Paulus, 2017). This seems to be consistent with other research regarding learning processes. Porter et al. (2020) focused on mastery behaviours, e.g., seeking challenges or persistence after setbacks, considered to advance learning effectiveness. In a series of five studies, they revealed the role of IH as a positive predictor of mastery behaviours when learning.

Intellectually humble people also differed in other indicators of cognitive functioning from non-humble ones. Those high in IH showed higher competencies in dealing with conflicting arguments, i.e., they focused more attention on the evidentiary basis and presented increased awareness of one’s own knowledge (Deffler et al., 2016; Leary et al., 2017). What is more, when given the possibility to read articles promoting or undermining one’s beliefs, people high in IH spent more time, compared to those low in IH, with articles that contradict their viewpoint (Deffler et al., 2016; Porter & Schumann, 2018). This effect can be interpreted as a function of curiosity or critical thinking. A significant role of IH in predicting lower certainty of one’s beliefs was also observed by Leary et al. (2017). Interestingly, a similar effect was found in another study that employed EEG methodology (in contrast to self-report as a dominant approach in this field of research). Danovitch et al. (2019) observed that IH correlated positively with brain potential Pe (200-400 ms), which relates to the conscious process of error detection. This suggests that intellectually humble people may present increased sensitivity to errors and, in turn, lower certainty of their own beliefs.

Wise reasoning is another relevant aspect of cognitive functioning when considering the significance of intellectual humility. Kross and Grossmann (2012) conceptualise wise reasoning as consisting of dialectical thinking and intellectual humility. Psychological distance turned out to have an important role in wise reasoning because it significantly affected the quality of judgements. Participants presented a higher level of wise reasoning when the issues discussed concerned other social groups in contrast to one’s own social group (Huynh et al., 2017; Kross & Grossmann, 2012). It suggests that psychological distance may increase manifested IH due to the potential mechanism of decreasing emotional involvement and increasing objectivism.

The research summarised above provides empirical arguments for conceptualising IH as a special epistemic virtue (e.g., Church & Samuelson, 2017), which inclines people to be aware of their knowledge and its limitations. However, it is not only the matter of a cognitive attitude or specific mind-set, since IH may also lead to behaviours characterised by open-mindedness, curiosity and constructive critique. Interpersonal and social domains are among those where this effect is most evidently seen.

SOCIAL AND INTERPERSONAL DOMAIN

The second core aspect of IH concerns interpersonal functioning. It seems likely that people with different levels of dispositional IH will present different social characteristics. This hypothesis has been confirmed across many studies. An evolutionary-epistemological account of IH assumes that people are naturally inclined to be intellectually arrogant, which is an evolved adaptation to the demands of a social world (Gregg & Mahadevan, 2014). Similarly to other domains of their lives, people experience their personal beliefs as important possessions (mental materialism) and are motivated to fight for their protection (ideological territorialism). Intellectual humility, as a less natural tendency, correlates negatively with tendencies to prefer and protect one’s own beliefs (Gregg et al., 2017).

Conversely, positive correlations were found between IH and measures of empathy, benevolence and altruism (Krumrei-Mancuso, 2017). IH was also found to moderate the affective polarisation between opposing social groups (e.g., liberals-conservatives, Democrats-Republicans). The affective polarisation refers to differences in affect toward one’s own and an opposing group. Typically, the affect toward one’s own group is warmer than to an opposing group; however, Krumrei-Mancuso and Newman (2020) found that this tendency is decreased when the IH is high. Intellectually humble individuals were less susceptible to affective polarisation. Similar effects were found, e.g., by Bowes et al. (2020) and Stanley et al. (2020) – they found that IH weakened the devaluation of political opponents’ moral character and competences.

While self-report measures of IH were used in the studies mentioned above, other studies focused on the perceived level of IH in others. Firstly, it should be highlighted that the correlations between self-report and other-report measures of IH are at most low. To gain a higher similarity between the two measures, people should know the persons being described very well (Meagher et al., 2015). Notwithstanding these methodological issues, interesting results of studies using other-report measures were found. Studies that focused on the perception of IH in others found that those perceived as intellectually humble were liked more than non-humbles. This general tendency was observed both for children and adults (Hagá & Olson, 2017; McElroy et al., 2014). Interestingly, this effect was stronger when describing a discussion opponent, because humility soothes a conflict and opens an opponent’s mind to one’s own view. On the other hand, IH across one’s own group is appreciated less because it raises the probability of acceptance of the others’ beliefs, which disrupts the default tendency to defend one’s own view (attitude justification hypothesis, see Wilson et al., 2017). Interesting effects regarding styles of leadership have also been revealed. Krumrei-Mancuso (2018b) found that both self-reported and perceived higher levels of IH predicted a leadership characterised by a motivation to serve rather than to lead.

The studies described above showed that IH is associated with a wide range of interpersonal functioning characteristics usually regarded as positive. Some exemplary characteristics are empathy, open-mindedness or more complex phenomena, such as willingness to forgive (Hook et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). Still, humble attitudes sometimes impede self-presentation and highly competitive task performance and increase the risk of being dominated or exploited (see Dik et al., 2017; Van Tongeren & Myers, 2017). This points to potentially negative, interpersonally related aspects of IH as well.

RELIGIOSITY

Humility is an important moral virtue emphasised in various religious systems (Heft et al., 2011; Hill, 2019; Porter et al., 2017). That is why many researchers have been interested in the relationships between IH and different aspects of religiosity. Some effects are relatively easy to predict, knowing the empirical results pertaining to the cognitive and social domain; however, there have been studies that drew counterintuitive conclusions as well.

Primarily, IH was found to be associated with religious exploration, religious tolerance and lower fundamentalism (Hodge et al., 2019, 2020; Hook et al., 2017; Jankowski et al., 2019). These characteristics can be generally understood as a manifestation of open-mindedness. Moreover, intellectually humble people were questioning their own faith and tended to verify it by searching for the truth (Hodge et al., 2019). Intellectually humble individuals demonstrated a higher ability to deal with arguments in a relatively objective way as well. In line with this, IH decreased the tendency to assign higher ratings for the religious articles and authors who favoured one’s own religious beliefs, compared to those who contradicted them (Hopkin et al., 2014). What is more, as mentioned above, when both self-measured and perceived in others, IH correlated positively with a willingness to forgive a religious group’s leaders their moral offenses. This tendency was observed across victim-offender relations when someone was hurt in the domain of religion-related emotions or beliefs (Zhang et al., 2015) as well as when the leader of one’s own religious group radically broke their group’s moral standards (Hook et al., 2017).

Hodge et al.’s research (2019, 2020) showed that religious IH – a domain-specific IH pertaining to religious beliefs – correlates negatively with conservatism and, in turn, might be associated with a liberal stance. Moreover, the current level of IH was found to negatively predict past (recalled) reasons for abandoning religious faith (Marriott et al., 2019). It means that humble people’s faith may be independent of childhood-related factors, such as the parents’ faith. Interestingly, intellectually humble religious leaders were more open-minded to integrating psychological knowledge with their church ministry (Hodge et al., 2020). They trusted psychiatrists and psychologists more, and in turn, recommended mental health therapy for their parishioners more often. Another study showed that a high level of perceived IH of religious discussion partners promoted belief change and significantly predicted feelings of closeness and trust during a discussion (Rodriguez et al., 2019).

Generally, IH was found to be associated with adaptive psychological characteristics. But as was mentioned, there are studies suggesting a more complex nature of IH, including less intuitive or even contradictory results. Jankowski et al. (2019) observed a surprising indirect relationship between IH and well-being. They found that religion-specific IH correlated positively with an insecure God attachment, which, in turn, correlated negatively with mental health. Importantly, this indirect effect was significant only when general humility was low. This result refuted the authors’ hypothesis. What is more, there is no consensus about a general relationship between IH and level of religiosity. Despite current studies that suggest an U-shaped relationship, the obtained results showed different effects. According to Hopkin et al.’s study (2014), moderate believers presented higher IH than radicals and non-believers. However, Krumrei-Mancuso (2018a) observed an inverse pattern, in which non-believers and radical believers were characterised by higher IH, compared to moderate believers. Thus, it seems that more research is needed to draw clear conclusions regarding this issue. Moreover, some researchers suggest that a theistic IH, i.e., “the way intellectual humility is experienced by theists”, should be conceptualised and measured as a separate construct (Hill et al., 2021, p. 155).

THE PROSPECTS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL RESEARCH ON INTELLECTUAL HUMILITY

The concept of intellectual humility is relatively new in psychological research, although the phenomenon of being intellectually humble has been present in philosophical and theological thought since antiquity (see Heft et al., 2011; Macaskill, 2018; Snow, 2021). It is not completely new in psychology either, since similar or related concepts have been emphasised and explored in some classical personality theories. Though the most recent studies point to the need to explicitly distinguish intellectual humility as a theoretical concept in its own right, much work still has to be done to define the relationships of IH with such concepts as wisdom (Grossmann, 2017), dogmatism (Altemeyer, 1996; Duckitt, 2009), need for cognition (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982; Petty et al., 2009), need for closure (Kruglanski & Webster, 1996), openness to experience (McCrae & Sutin, 2009) or the HEXACO honesty-humility dimension (Lee & Ashton, 2004). The empirical studies from the last six to seven years that focused explicitly on IH have produced quite a few promising results. They point to the potential role that intellectual humility plays in many domains of human life, including cognitive functioning and the processing of information, interpersonal relationships, religion, politics, etc. The studies reviewed above do not exhaust all relevant topics. As an example, let us point to the very current, pandemic-related issue. Two interesting recent studies showed a negative relationship between intellectual humility and anti-vaccination attitudes related to both flu (Senger & Huynh, 2020) and COVID-19 (Huynth & Senger, 2021). The number of published studies is constantly growing but, so far, most of them have utilised a cross-sectional design for which self-report was the predominant approach to measuring IH (Hoyle & Krumrei-Mancuso, 2021). This points to the limitations of existing research and potential directions for future studies.

Most of the studies to date have used self-report measures of IH. Several questionnaires have been proposed so far, such as the Limitation-Owning Intellectual Humility Scale (Haggard et al., 2018), Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale (Krumrei-Mancuso & Rouse, 2016), General Intellectual Humility Scale (Leary et al., 2017) and Specific Intellectual Humility Scale (Hoyle et al., 2016), to list just the most often used. Notwithstanding the utility of self-report measures in general, as well as their contribution to intellectual humility research in particular, there is a paradox in self-reporting about humility. A high level of this trait predisposes to being modest in perceiving and subsequent reporting one’s own humility. Thus, those who are humble may, in fact, score lower on self-report questionnaires designed to measure IH (Hoyle & Krumrei-Mancuso, 2021; Leary, 2017). Humble individuals may underestimate the level of their humility because they “sense that claiming to be very humble would be immodest, akin to bragging about one’s humility” (Davis et al., 2010, p. 245). However, this is not to suggest that self-report measurement of IH should be entirely abandoned, but rather that it should be supplemented with other types of measurements.

An alternative to a self-report is a peer-report (observer-report) approach, where a participant of a study reports on the perceived IH of someone else. Implementing this approach in psychological research has led to interesting results regarding the impact of a perceived actor’s IH on social bonds (McElroy et al., 2014) and related willingness to forgive an actor’s transgression of important norms (Hook et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). The peer-rating format of the assessment of humility has been employed, e.g., in the Intellectual Humility Scale (IHS) by McElroy et al. (2014) and the Expressed Humility Scale by Owens et al. (2013).

Besides the verbal reporting of IH, regardless of whether it is a self- or peer report, there is a need for measures that are based on behavioural indicators. A promising attempt here is the Implicit Association Test of Humility by Rowatt et al. (2006), based on a standard implicit association test (Greenwald & Farnham, 2000). Still, it seems that this is just the beginning of developing behaviour-based measures of IH, and much work is yet to be done here. The need to go beyond verbal reports of IH is especially relevant if the research is to go further than just describing the pattern of relationships between IH and other variables. A significant challenge for the researchers in the field is to develop effective manipulation procedures that allow for experimental designs with IH serving as an independent variable. To do so, valid measures are needed that are capable of capturing the situational variability of IH at a state level in contrast to a trait level (see Leary, 2017). Some promising work has already been done here (Davis et al., 2017; Kruse et al., 2017; Weidman et al., 2018), though effective manipulation techniques are still lacking.

Apart from the measurement and procedural issues, new thematic areas of IH research are arising. Besides those briefly reviewed above, a particularly interesting topic is the relationship between intellectual humility and the self. Since IH refers to the awareness and assessment of one’s own intellectual abilities, it seems to be strongly entangled with self-related phenomena. The studies performed to date have addressed some important issues, such as the strength of self-serving biases (Reis et al., 2018) or the relationship between IH and self-esteem vs. narcissism (Alfano et al., 2017; Bąk & Kutnik, 2021; Krumrei-Mancuso & Rouse, 2016). However, many interesting questions still await empirical examination. For instance, does the level of IH affect the content and structure of one’s self-concept and identity? We would expect a positive relationship with self-concept clarity (Campbell et al., 1996), i.e., that self-knowledge of intellectually humble individuals is more clearly and confidently defined as well as more stable temporarily. Given the above described relationships with personality traits we would also postulate that IH promotes the effectiveness of self-regulation with regard to one’s own goals and standards (see, e.g., McCrae & Lockenhoff, 2010).

The list of compelling questions and important research problems is much longer. Successive improvement of research methods and the accumulation of empirical results published in top psychological journals over the last few years allow us to predict that the subject of IH will attract the attention of more and more researchers. Thus, after hundreds of years of being discussed within philosophical and theological thought, intellectual humility is going to become one of the intriguing issues examined by scientific psychology.