Introduction

Complete mesocolic excision (CME) was first described by Hohenberger et al. [1] to standardize colon cancer surgery for better oncological outcomes. The essentials of CME for right sided colon cancer are central vascular ligation, sharp dissection of the mesocolon between proper planes and harvesting sufficient lymph nodes with minimally 10 cm proximal-distal resection margins [2]. Hohenberger’s CME was originally described for open surgery, but laparoscopic CME and various techniques have been reported in recent years [3–5].

Laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery has been shown to provide short-term oncological results similar to open surgery [6, 7]. Laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection is a safer, faster and a less traumatic alternative to traditional laparotomy. It has various advantages such as reduced trauma, stress, and pain. Although a uniform standard procedure is not yet available, many approaches have been proposed to address this complex surgery. “Medial-to-lateral”, “lateral-to-medial”, “top down no touch” and the “cranial-to-caudal” [8, 9] techniques are some of these approaches for right sided colon cancers.

Aim

The aim of this study was to provide an overview of the laparoscopic transmesocolic approach for right sided colon cancers.

Material and methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Date 2022-01/No. 13).

Between 2010 and 2020, 26 patients with right sided colon cancer who had undergone laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with this technique were included in this study. All operations were performed by the same surgical team. Operational and demographic data, pathologic results, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), tumor location, tumor depth, TNM, number of harvested lymph nodes, operation time, transfusion amount and hospital stay length were recorded.

Patient position

The patient was placed in a supine position with the legs apart. The position was then changed to Trendelenburg tilt with the left side down. Surgeons stood between the legs, whereas the assistant stood at the left side of the patient.

Trocar position

Four trocars (two 10 mm ports for the camera and the working port and two 5 mm ports for the other working and assistant ports) were used in the surgery. We sometimes use a fifth trocar (12 mm) for intracorporeal side-to-side stapled anastomosis, but we usually prefer changing one 10 mm trocar to a 12 mm trocar for the anastomosis.

Surgical technique

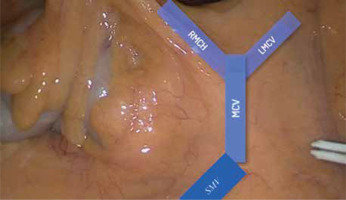

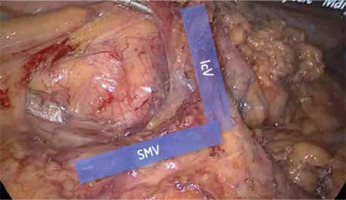

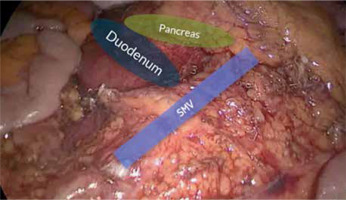

Surgery started with dissection of the transverse mesocolon directly above the middle colic artery (MCA) (Photo 1). The right branch of the middle colic artery (rMCA) was exposed and ligated at its origin. Secondly, the omental bursa was opened through the mesocolon. Then, the gastrocolic trunk of Henle was exposed and the right colic vein (RCV) and the right gastroepiploic vein (rGEV) were identified and ligated. Dissection was continued caudally using the cranial-caudal approach above the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) (Photo 2). In the meantime, the pancreatic head and the duodenum were separated from the mesocolon. Thirdly, the ileocolic artery and vein were identified and ligated at their origins. The descending and the transverse mesocolons were separated from the retroperitoneum, duodenum, and the pancreatic head (Photo 3). Following the dissection of the mesocolon, the lateral attachments and the hepatic flexure of the right colon were dissected and separated. Finally, the proximal and the distal margins of resection were determined, and the resections were fully completed. Intracorporeal side-to-side anastomosis was made using endoscopic staples.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee (Date 2022-01/No. 13).

Statistical analysis

The descriptive data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or number and percentage. For distribution of data the Shapiro-Wilk test was used. The continuous variables were tested using the independent sample t test. For categorical variables the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used where applicable. A p-value 0.05 was considered as being statistically significant.

Results

The demographics of 26 patients are presented in Table I. The mean age was 59.3 ±16.1. There were 15 female and 11 male patients with a mean BMI of 25.9 ±16.1 kg/m2. In 4 patients, the cancer occurred in the appendix (15.4%), 11 (42.3%) patients had tumors of the caecum, 10 (38.4%) patients had ascending colon tumors, 1 (3.8%) patient had the tumor at the proximal hepatic flexure.

Table I

Demographics of patients

The operative data and the postoperative findings are presented in Table II. The mean operative time was 137.6 ±19.4 min. The mean length of hospital stay and time to first flatus were 7.5 ±4.6 days and 2.3 ±1.5 days, respectively. None of the patients were re-admitted to the hospital in 30 days. There was no 30-day mortality in the patients. There were no major complications. Four patients had wound infection at the extraction site and 1 patient had postoperative ileus, which was managed with nasogastric tube decompression and no need for further interventions.

Table II

Operative data and postoperative findings

The pathological findings are presented in Table III. The mean proximal, distal, and radial margins were 17.6 ±6.9 cm, 21.4 ±7.6 cm, and 4.2 ±1.7 cm, respectively. The mean total lymph node number was 39.3 ±15.3 with a range between 13 and 74. Twenty-two patients had a resection in the mesocolic plane, and in 3 cases, the resection was in the intramesocolic plane. One of the patients with the resection in the intramesocolic plane underwent emergency surgery due to subileus.

Table III

Pathological findings

Discussion

Although mesenteric excision has long been practiced in colorectal cancer surgery, it has never been standardized for this type of procedure. CME is a technique based on the embryological concept of the enveloping layers of the visceral fascia covering the mesentery and lymphatic drainage. Recently, Hohenberger et al. [1] changed this concept for the first for open surgery. Compared to conventional right colon cancer surgery, CME focuses on maximizing the removal of regional lymph nodes and surgical margins based on embryological planes.

Several studies have suggested central vascular ligation (CVL) for a proper CME in patients with colon cancer for better oncological outcomes [1, 10]. Although CME was first described for the conventional open approach, laparoscopic CME has begun to be carried out since, approaching the same oncologic results compared to open surgery [4, 11]. Due to complex variations [12], laparoscopic surgery of the right colon is considered one of the most difficult procedures in colorectal cancer surgery. These anatomical variations are always challenging the surgeons to search for better laparoscopic techniques for an appropriate CME. Thus far, there is no current consensus on the optimal technique for right sided colon cancer patients [8, 9, 13–18]. Concerns have been raised about the technical demands of CME and the potential for complications during the procedure. Right hemicolectomy can be considered as one of the most challenging procedures due to the vascular anatomy. It is therefore suggested that strategies related to the division of the middle vessels be utilized in standard laparoscopy.

Due to the rapid development of CME and laparoscopic surgery, the 5-year overall survival rate for right colon cancer has increased from 82.1% to 89.1% [1]. Since Hohenberger’s pioneer study for CME, many studies have suggested and indicated the benefits of CME compared to non-CME resections for right sided colon cancer [19–21]. With a lateral approach, embryological fusion of the transverse colon to the adjacent organs can be completely reversed without damaging the mesocolon before separation of the vessels of the central colon. Therefore, a lateral approach, CME with CVL in right hemicolectomy, makes sense. However, use of the lateral approach in laparoscopic surgery is extremely challenging as the operating room and forceps maneuverability are significantly more limited in the laparoscopic setting.

In laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, CVL is used before folding of the transverse mesocolon and embryological fusion [22]. In contrast, open surgery involves the use of a lateral approach. In this technique, the transverse mesocolon can be reversed from the adjacent organs without causing any injuries to the mesocolon. The skills and experience of the surgeon are among the most important factors that determine the prognosis of patients after cancer surgery [23].

In the transmesocolic technique, we directly begin dissection above the duodenum through the transverse mesocolon. Recent studies showed that the incidence of right colic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery was just 33% [12]. In our experience, we believe that it is one of the safest ways to start dissecting due to the presence of fewer variations compared to the gastrocolic trunk of Henle (GTH). Our transmesocolic technique indicates some similar specialties to Benz et al.’s “uncinate process first” approach [24]. However, after creating the space above the duodenum, we directly dissect and ligate the right branch of the middle colic artery and enter the bursa omentalis. Dissection continues along the SMV and the ileocolic vessels are ligated. The dissection between the mesocolon and Gerota’s fascia continues to the abdominal wall.

Of course, for every surgical technique, safety must be one of the first considerations that should not be ignored. Perioperative complications are important indicators for showing whether the technique is safe or not. Dai et al. [21] analyzed the subgroup between CME and non-CME groups in their meta-analysis. They stated that there was no difference between laparoscopic CME and the non-CME group in terms of postoperative complications such as wound infection, anastomotic leakage, ileus, and postoperative hemorrhage. In our study, we also had low complication rates and had no mortality with this technique.

In our experience, the most important disadvantage of the transmesocolic technique is directly dissecting the mesocolon and reaching the right branch of the middle colic, which may sometimes be quite difficult, especially in obese patients. There are also some difficulties with this approach due to variations in the branching of the middle colic artery [25]. Another disadvantage of this technique is the difficulty of dissecting the mesocolon directly with locally advanced hepatic flexure and proximal transvers colon tumors. When we encounter these patients, we mostly prefer the lateral approach. When compared with the cases in which we performed the classic lateral approach in our clinic, it was seen that the only comparison with a statistically significant difference was the tumor location. We think that this difference occurs due to the patient selection because of disadvantages we have explained above. For this reason, it is important to use the transmesocolic approach in highly selected patients. This situation also explains the number of patients in our article. For all these reasons, the lateral approach may be more feasible with locally advanced and mesocolon invaded tumors. However, experienced hands and a high level of knowledge of anatomy facilitate dissection of the mesocolon and the MCA.

This study has limitations. Due to the retrospective design and the relatively small number of patients, the data should be considered tentative, in particular with regard to safety. In addition, the lack of long-term follow-up results of the patients is another disadvantage of the study.

Conclusions

The transmesocolic approach with CME seems technically feasible and a safe treatment for right colon cancer. More data from randomized trials are needed, not only on cancer endpoints, but also on more detailed short-term outcomes, to confirm the benefits of the transmesocolic approach and to summarize the advantages for the population.