Introduction

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and bronchodilators are the mainstay of treatment for asthma. Regular use of ICS controls the underlying airway inflammation and consequently decreases the risks of asthma exacerbation and death [1, 2]. In contrast, bronchodilators, such as inhaled β2-agonists, quickly relieve asthma symptoms, but do not alleviate the underlying inflammation [3, 4]. Unfortunately, overreliance on bronchodilators without ICS can mask the progression of asthma, thereby increasing the risk of serious exacerbations [5, 6]. In particular, frequent use of short-acting β2-agonists (SABA) has been linked with poor outcomes in patients with asthma, including increased risks of hospital admission, disease exacerbation, and death [7–11].

Aim

Although current treatment guidelines warn against overreliance on SABA in asthma, large studies in North America and Europe have shown that SABA are still frequently overused [12–15]. However, there is little evidence, on the risk factors for SABA overuse in asthma [16]. Identifying these factors could help develop strategies to improve patient outcomes. Within a range of anylyses performed within SABINA project [12], we aimed to analyse a nationwide database of prescription purchase records to investigate the risk factors for SABA overuse and asthma exacerbations among patients with asthma in Poland.

Material and methods

Study design

We analysed prescription purchase records in the PEX PharmaSequence database that includes 5,172 pharmacies with a geographic distribution representative for Poland. Medication name, quantity, form, and dose; specialty of the prescriber; and patient’s sex and age were available from the purchase records. In the database, information on the prescriber’s specialty was missing at random in about 25% of records for blinding reasons in line with local law regulations. The records did not include the indications (diseases) for prescriptions. Patient allocation to the predefined cohort was based on a pattern of prescriptions for inhaled respiratory medications described below.

Patient selection

We selected patients aged 18–64 years with ≥ 1 prescription purchase for ICS (excluding nebulized ICS), SABA, leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA) or short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMA), or combinations thereof, in the two following periods: January to June 2018 and July to December 2018 (Figure 1) [15]. We excluded patients who only purchased long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) in any quarter of 2018 as these patients were likely undergoing treatment for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Thus, we selected subjects in whom asthma diagnosis was highly probable. Among the patients with asthma, we analysed those with ≥ 1 prescription purchase of SABA. Additionally, to confirm the applicability of our findings to asthma, we performed sensitivity analyses in a sub-group of patients aged 18–35 years in whom COPD was unlikely (reported in the Supplementary materials). As this study was a retrospective analysis of anonymised data, ethics approval was not needed.

Variables

Variables were obtained based on the data available from prescription records. Secondary care was defined as ≥ 1 prescription from a pulmonologist or allergist. The number of SABA puffs per year was calculated as the total number of individual SABA doses in all canisters purchased by a patient. One canister was defined as 200 inhalations [15]. To evaluate SABA prescriptions, we adopted two levels of SABA purchase per year: SABA overuse and excessive SABA use [15, 16]. Excessive SABA use was defined as ≥ 12 SABA canisters purchased over a year [17]. SABA overuse was defined as ≥ 3 SABA canisters purchased over a year. The number of prescriptions for oral corticosteroids (OCS) during the study period was taken as a proxy of asthma exacerbations. The dose of OCS was calculated in prednisone equivalents according to standard equations (http://www.medcalc.com/steroid.html).

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics in accordance with data distribution. Quasi-Poisson regression was used to study the association of age, sex, type of inhaled treatment (“SABA without steroids” as reference), secondary care (primary care as reference), and place of residence (< 100,000 inhabitants as reference) to excessive SABA use and SABA overuse. Patients with prescriptions for 1–2 SABA canisters were the reference group. Negative binomial regression was used to analyse the association of excessive SABA use and SABA overuse with the number of prescriptions for OCS. We analysed the risk of asthma exacerbation (OCS prescription) in two negative binomial regression models: among all patients and among patients with ≥ 1 exacerbation. A p < 0.05 was considered significant. All calculations were completed in the R software (version 3.5.5).

Results

Patient characteristics and SABA use

In total, 91,763 patients met the inclusion criteria for asthma (Figure 1). Of them, 42,189 (46%) had concomitant prescriptions for SABA (SABA users). These patients had a mean age of 47 years, and were mostly female (58%). Of the SABA users, 20% did not use ICS, 11% used SABA and ICS, and 69% used SABA, ICS, and LABA (Figure 1, Table 1).

Table 1

Patient characteristics

Of the 42,189 SABA users, 14,145 (34%) purchased ≥ 3 SABA canisters (SABA overuse), and 2,359 (6%) purchased ≥ 12 SABA canisters (excessive SABA use). SABA use was most frequent among patients who did not use ICS, including the largest number of purchased SABA canisters and the percentages of excessive SABA use and SABA overuse (Table 1).

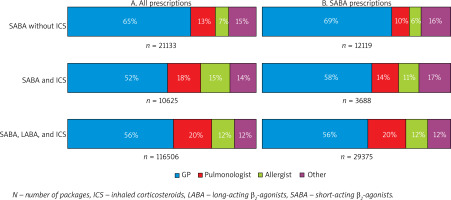

In all study groups, most prescriptions for all medications, including SABA, were issued by general practitioners (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Prescriptions by specialty for all medications (A) and SABA (B) for patients with different types of inhaled treatment

The percentage of patients with prescriptions for OCS was the greatest among patients who used SABA, ICS, and LABA, but the number of prescriptions and the total dose of OCS were highest among those who did not have prescriptions for ICS (Table 1).

Predictors of excessive SABA use and SABA overuse

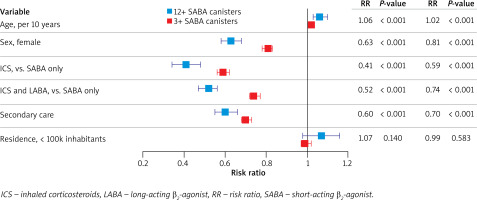

Older age was associated with a higher risk of excessive SABA use (risk ratio (RR) = 1.06, p < 0.001), whereas the risk was lower in women (RR = 0.63, p < 0.001), patients treated by specialists within secondary care (RR = 0.60, p < 0.001), and patients who used ICS without LABA (RR = 0.41, p < 0.001) or with LABA (RR = 0.52, p < 0.001). Place of residence was not significantly related to excessive SABA use or SABA overuse. The predictors of SABA overuse were similar to those for excessive SABA use (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Predictors of excessive SABA use (≥ 12 canisters) and SABA overuse (≥ 3 canisters) by quasi-Poisson regression. Patients with prescriptions for < 12 or < 3 SABA canisters were respective reference groups. Predictors: age (per 10 years); male sex (vs. female); ICS (vs. SABA only); ICS and LABA (vs. SABA only); secondary care (vs. otherwise); place of residence with > 100,000 inhabitants (vs. ≤100,000 inhabitants). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals

Predictors of asthma exacerbations

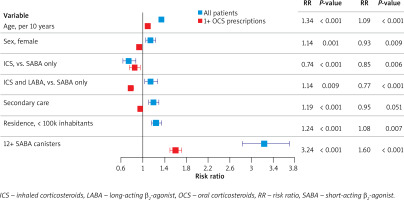

Excessive SABA use was the strongest predictor of asthma exacerbations both in the model that included all patients (RR = 3.24, p < 0.001) or patients with ≥ 1 OCS prescription (RR = 1.60, p < 0.001; Figure 4). In the entire cohort, the risk of exacerbation was increased in older patients (RR = 1.34, p < 0.001), women (RR = 1.14, p = 0.001), patients in secondary care (RR = 1.19, p < 0.001), patients who used ICS with LABA (RR = 1.14, p = 0.009), and patients who lived in places with < 100,000 inhabitants (RR = 1.24, p < 0.001); the risk of exacerbation was lower in patients who used ICS without LABA (RR = 0.74, p < 0.001; Figure 4).

Figure 4

Predictors of asthma exacerbations by negative binomial regression among all patients and patients with ≥ 1 prescriptions for oral corticosteroids. Model with ≥ 12 SABA canisters. Predictors: age (per 10 years); male sex (vs. female); ICS (vs. SABA only); ICS and LABA (vs. SABA only); secondary care (vs. otherwise); place of residence with > 100,000 inhabitants (vs. ≤ 100,000 inhabitants); ≥ 12 SABA canisters (vs. < 12 canisters). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals

Among patients with ≥ 1 exacerbation, the risk of exacerbation was lower in women (RR = 0.93, p = 0.009), patients in secondary care (RR = 0.95, p = 0.051), and patients who used ICS without LABA (RR = 0.85, p = 0.006) or with LABA (RR = 0.77, p < 0.001; Figure 4); the risk of exacerbation was higher among older patients (RR = 1.09, p < 0.001) and in patients who lived in places with < 100,000 inhabitants (RR = 1.08, p = 0.007; Figure 4).

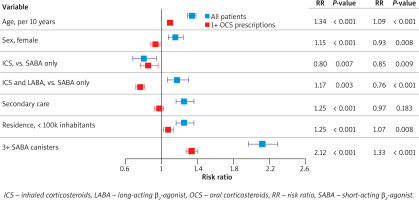

Similar results were found in the models that included SABA overuse (i.e., ≥ 3 SABA canisters; Figure 5). Sensitivity analyses among patients aged 18–35 years (Supplementary materials) showed essentially the same findings as the main analysis.

Figure 5

Predictors of asthma exacerbations by negative binomial regression among all patients and patients with ≥ 1 or more prescriptions for oral corticosteroids. Model with ≥ 3 SABA canisters. Predictors: age (per 10 years); male sex (vs. female); ICS (vs. SABA only); ICS and LABA (vs. SABA only); secondary care (vs. otherwise); place of residence with > 100,000 inhabitants (vs. ≤ 100,000 inhabitants); ≥ 3 SABA canisters (vs. < 3 canisters). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals

Discussion

We found that 46% of patients with asthma in Poland used SABA, of whom 20% used SABA without concomitant ICS or ICS/LABA prescriptions. Moreover, 6% of patients used SABA excessively, and 34% overused SABA. The risk of excessive SABA use was twice as high in patients who did not use ICS. Excessive SABA use was the strongest predictor of asthma exacerbation, tripling the risk.

In the study period (i.e., 2018), the use of SABA without ICS could be expected in selected patients with very mild disease in line with the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) recommendations at that time (GINA 1). However, we found that patients who did not use ICS had the poorest asthma control, as indicated by the greatest consumption of SABA and OCS (which we used as a proxy of asthma exacerbations). Thus, we hypothesize that this group of patients included those with severe disease, who did not receive adequate maintenance treatment.

Our results also showed there is a substantial proportion of patients with asthma who use SABA excessively. The percentage of excessive SABAs users in our study (6%) was similar to that observed in France (~5%), lower than in the United Kingdom (~10%), but higher than in Canada (~1%) [13, 16]. Moreover, in our study, about one-third of patients could be defined as SABA overusers (≥ 3 canisters), which is similar to a recent study from Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom [15]. In Poland, SABAs are available on prescription only; thus, SABA overuse is most likely related to overprescription. Importantly, a survey in a primary care setting in Poland showed that physicians tend to prescribe SABA on patients’ request (“physician acceptance”, data not published).

Although it is well accepted that ICS are currently the most effective medications for controlling asthma-related inflammation in the airways, data on the association between ICS treatment and the risk of excessive SABA use are scarce. Indeed, to our knowledge, only one previous study showed that “appropriate use of ICS” substantially decreased the risk of excessive SABA use [16]. Similarly in our cohort, a lack of prescription for ICS was the strongest predictor of excessive SABA use, with the risk doubled compared to patients who used ICS. These findings strongly support the new GINA recommendations to use ICS whenever SABAs are used [1]. This recommendation should reduce the prevalence of excessive SABA use and its consequences such as a lack of asthma control, asthma exacerbations, and asthma-related deaths [18, 19].

We also found that secondary care provided by an asthma specialist was associated with a 40% reduction in the risk of excessive SABA use, in line with the published work [20]. This indicates that non-specialists, primarily general practitioners, may under-prescribe ICS to people with asthma. Thus, excessive SABA use could be reduced through education of general practitioners or by increasing the availability of secondary care. In line with reported data, excessive SABA use was also associated with older age and male sex, which could be due to more severe disease in older people and to better adherence to controller medications among women [16, 21].

In our study, excessive SABA use best predicted asthma exacerbations, tripling the risk in the entire cohort, and increasing it by 60% among the patients with ≥ 1 exacerbation. Similarly, SABA overuse doubled the risk of asthma exacerbation in the entire cohort, and increased it by one-third among patients with exacerbations. Our results agree with previous studies in which the overuse of SABA was the single most important predictor of asthma exacerbations [8, 22]. Importantly, the use of ICS was associated with a decreased risk of asthma exacerbations independently of excessive SABA use (by about 20%). In the entire cohort, the exacerbation risk was increased among patients who used ICS and LABA, which likely reflects a more severe disease course in this group. Indeed, the analysis among patients with ≥ 1 exacerbation (indicating similar disease severity) showed that concomitant ICS and LABA use was associated with an even lower risk than the use of ICS alone. This is in line with recent findings of four prospective, randomized, controlled trials, in which ICS/LABA combination was associated with a lower risk of asthma exacerbation (by ~20%) [23]. Similarly, secondary care seemed to be an indicator of more severe disease in the entire cohort [24], with an increased risk of exacerbations. In contrast, secondary care was associated with a reduced exacerbation risk among patients with similar disease severity (≥ 1 exacerbation).

Our results confirm previous findings that the risk of asthma exacerbation seems to be greater among older people and in women, who tend to have more severe disease [22, 25]. Interestingly, among patients with similar disease severity (≥ 1 exacerbation), women had a lower risk of exacerbation, which could be due to better adherence to controller medications [21]. We also found that living in a place with < 100,000 inhabitants was related to a higher risk of exacerbation, which could reflect reduced access to secondary care outside large cites.

The limitations of our study need to be mentioned. First, we analysed data from individual prescriptions that did not include information on the diagnosis (e.g., asthma, COPD), and defined “asthma” based on a typical pattern of prescriptions. Second, we did not have access to the clinical characteristics of patients, such as asthma severity or comorbidities. Third, the selection of older patients (45–64 years) might be associated with the risk of including patients with COPD or the asthma-COPD syndrome; however, sensitivity analyses among patients aged 18–35 years (Supplementary materials) showed essentially the same findings as the main analysis. Fourth, because the data were obtained from pharmacy records, our analysis was limited to out-patient events. Fifth, the asthma exacerbation was defined as a prescription for an OCS, which could underestimate the number of exacerbations. On the other hand, OCS can be prescribed for other reasons than an asthma exacerbation. Finally, in contrast to previous studies, we could not analyse other outcomes such as hospitalizations or deaths [11].

A large cohort of patients is an important strength of our study. We also used a database of purchased medications, which is a more reliable approach than considering issued prescriptions only that may or may not be filled. Therefore, estimates of SABA consumption from our study seem to accurately reflect the real use of these medications. Moreover, our database allowed for multivariate analyses of study predictors of SABA overuse and its relationship to asthma exacerbations.

Conclusions

The frequency of SABA overuse was high in Poland, as observed previously in other European countries [15]. SABA overuse is an important predictor of unfavourable asthma outcomes and, therefore, efforts should be made to decrease its frequency. SABA overuse should be flagged in electronic quality control systems to identify patients at risk and physicians who overprescribe SABA. Our data add important evidence that ICS-based controller treatment is essential to reduce SABA overuse. Thus, our results support the new GINA recommendations to use ICS-based controller treatment in all patients with asthma [1]. Other ways of reducing excessive SABA use should also be considered, such as educating physicians on the treatment guidelines, expanding access to secondary care for patients with asthma, and educating patients on the risks of SABA overreliance.