Introduction

Leishmaniasis is an euglenozoan parasitic vector-borne infection endemic in 98 countries, with over 350 million people at risk globally [1]. The disease occurs in three main forms: (a) visceral leishmaniasis (VL), or kala-azar, the most severe form, fatal in 95% of untreated cases, characterized by recurring fever, wasting, anemia, and hepatosplenomegaly; (b) cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) which causes skin lesions such as ulcers on exposed parts of the body and may lead to scarring; and (c) mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL), or espundia, a form involving the mucous membranes of the nose, mouth and throat and leading to facial disfigurement [2].

Leishmania can be divided into Old World and New World species. Old World CL acquired in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Mediterranean/Southern Europe is transmitted by sandflies of the genus Phlebotomus. Major causative species include Leishmania major, L. tropica, L. infantum, L. donovani, and L. aethiopica. Old World CL is usually a benign cutaneous disease without spread to mucosal sites. L. infantum and L. donovani also cause visceral leishmaniasis, but it is seldom concomitant with the cutaneous form. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis is endemic throughout Latin America, ranging from Mexico to Argentina; it is transmitted by sandflies of the Lutzomyia genus. The disease caused by the members of the Vianna subgenus including Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis, L. (V.) guyanensis, L. (V.) panamensis, and L. (V.) peruviana may be locally aggressive and can progress to the destructive mucocutaneous infection. The species of the Leishmania subgenus present in the New World include L. mexicana, L. amazonensis, L. venezuelensis, and L. infantum (= L. chagasi); the disease caused by them almost never involves the naso- or oropharyngeal mucosa [1, 3]). Recently, some novel species causing the disease in humans have been identified both in the Old and the New World [4]. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is transmitted either in the anthroponotic (primarily L. tropica and L. donovani) or zoonotic cycle (all other species). Non-vector transmission (e.g. by accidental laboratory infection or intravenous drug use) is rare [3].

The disease is present mainly (but not exclusively) in the tropical and neotropical low-income countries, with malnutrition, population displacement, poor housing, impaired immunity and poverty constituting the most important factors facilitating its spread [2, 3]. Although the burden of CL is in some countries high [5, 6] and the disease often has serious long-lasting psychosocial consequences [7], it is rarely fatal, which is why the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared it one of the 17 neglected tropical diseases [2].

Although it has been estimated that 1.5–2 million new cases of CL occur every year [8], the real global incidence of CL is probably higher because of asymptomatic or misdiagnosed cases [3, 9]. The trends in numbers of new cases of CL vary depending on location: the numbers are increasing significantly in the high-burden countries of the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region but they are stable in the high-burden countries elsewhere [2, 6]. The numbers of imported cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis are also increasing according to reports from other non-endemic European countries, making CL the most common clinical form of imported leishmaniasis [10].

Poland has been a country with no autochthonous cases of leishmaniasis detected [10]. The disease is not notifiable according to the national law [11], and the incidence of CL importation is unknown, similar to many other non-endemic countries [10].

Aim

The aim of this study was to investigate and present the clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of the cases of CL treated at the University Center for Maritime and Tropical Medicine, Gdynia, Medical University of Gdansk, one of the two tertiary reference centers for tropical medicine in Poland, in the years 2005–2017.

Material and methods

A list of all patients diagnosed with cutaneous leishmaniasis at the Department of Tropical and Parasitic Diseases, University Center for Maritime and Tropical Medicine, Gdynia, Medical University of Gdansk, was obtained by an automated query in the electronic database of patients’ medical files.

All patients, in whom CL was suspected, were clinically evaluated and Giemsa-stained impression smears from the ulcerative lesion or from fresh tissue bioptates were examined for the presence of the amastigotes. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was also used to detect the DNA of Leishmania spp. in tissue bioptates from 2009 onwards, as described in our earlier studies [12, 13].

The study was conducted in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Gdansk. For this type of the study, no formal consent is required.

Results

Altogether, 14 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis were identified among the patients treated at the Department in the years 2005-2017. Their demographic and clinical data are summarized in chronologic order in Table 1, including age, sex, areas visited, purpose of travel, time from onset of symptoms to correct diagnosis, appearance of lesions, results of impression smears and PCR, and superinfection if detected.

Table 1

Demographic and clinical data of the studied group, in chronological order

| Patient | Age | Sex | Travel destination | Purpose of travel | Appearance of lesions | Time from onset to diagnosis | Microscopic examination | PCR | Species | Superin-fection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | M | Nepal | Tourism | Blisters with erythematous background on the face and limbs | Unknown | Positive | Not performed | Unknown | S. pyogenes S. aureus mssa |

| 2 | 26 | M | Belize | Military | Inflammatory infiltration and ulcerations of the fifth finger and wrist of the left hand | 4 months | Positive | Not performed | Unknown | None |

| 3 | 61 | M | Madagascar | Tourism | Ulcerations of upper and lower limbs | 1 month | Negative | Not performed | Unknown | S. pyogenes |

| 4 | 49 | M | Burkina Faso | Professional | Ulceration of the umbilical area with small satellite nodules | 5 months | Positive | Positive | L. major | None |

| 5 | 26 | M | Chad | Military | Ulceration of the left hand | 1 month | Negative | Positive | L. major | None |

| 6 | 60 | M | Turkme-nistan | Professional | Upper left limb ulceration | Several months | Positive | Positive | L. major | S. haemolyticus S. marcescens |

| 7 | 27 | F | Cuba | Tourism | Hard, exudative lesions on the crus, finger, later disseminated papules | 5 months | Negative | Positive | Unknown | None |

| 8 | 27 | M | French Guyana | Tourism | Round erythematous foci on the trunk and upper limbs | Unknown | Positive | Positive | Unknown | Fungal |

| 9 | 23 | M | Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, Turkey, Iran | Tourism | Right crus ulceration | 4 months | Negative | Positive | Unknown | None |

| 10 | 30 | M | Thailand, Myanmar, Southern France | Tourism | Ulceration of the left axilla | Several months | Positive | Not performed | Unknown | None |

| 11 | 27 | M | Bolivia | Tourism | Papular lesions on the trunk and limbs | 2 months | Negative | Positive | Unknown | None |

| 12 | 29 | M | Bolivia | Tourism | Ulcerations of the dorsum and the second toe of the right foot | Unknown | Negative | Positive | Unknown | None |

| 13 | 28 | M | Peru | Tourism | Ulceration of the left forearm | 0 months* | Positive | Positive | Unknown | None |

| 14 | 25 | M | Bolivia | Tourism | Ulceration of the right lower limb (Fig. 2) | 3 months | Negative | Positive | Unknown | None |

General characteristics of the studied group

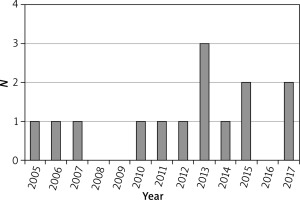

The majority of patients (n = 13; 93%) were male. The median age was 28.5 years (23–61 years). None of the patients was known to have any immunosuppression. The number of cases per year is presented in Figure 1.

Probable geographic origin of the infection and the purpose of travel

The patients travelled mainly to Central or South America (n = 7; 50%), Central or South East Asia (n = 4; 28.6%) and Africa (n = 3; 21.5%). The purpose of travel was mainly tourism (n = 10; 71.4%), followed by professional activities (n = 2; 14.3%) and military service (n = 2; 14.3%).

Clinical picture

The majority of cases presented themselves as a classical single ulceration (n = 7; 50%); in further 4 (28.6%) cases, the ulcers were multiple. Three (21.4%) cases had an unusual appearance: blisters with erythematous background (n = 1), hard exudative lesions with subsequent papular dissemination (n = 1), and papular lesions (n = 1). The eruptions were located mainly on limbs (n = 8; 57%), but also on the face and limbs (n = 1), trunk and limbs (n = 3; 21.5%) and the trunk only (n = 2; 14.3%).

Time from the onset of symptoms to correct diagnosis

The time from the onset of symptoms to correct diagnosis was known in 11 (78.6%) cases. It was up to 1 month in 3 (21.4%) cases, 2 or 3 months in 2 (14.3%) cases, 4 months in 2 (14.3%) cases and 5 or ‘several’ months in 3 (21.4%) cases.

Establishment of the diagnosis of leishmaniasis

The diagnosis was confirmed by the PCR alone in 6 (42.7%) cases, by the Giemsa stain alone in 4 (28.6%) cases and by both the PCR and Giemsa stain in 3 (21.5%) cases. In 1 case, the Giemsa stain was negative and the PCR was not yet available at the institution at that time, and therefore, the diagnosis was established solely based on the clinical picture and the response to treatment. The causative species was identified with gene sequencing as L. major in 3 (21.5%) cases, but the identification was not performed in the remaining 11 patients because of lack or failure of equipment at the time of diagnosis.

Treatment and outcomes

The majority of the patients (n = 10; 71.5%) were treated systemically: 7 (50%) patients with pentavalent antimonials, 2 (14.3%) with ketoconazole and 1 (7.1%) with miltefosine and ketoconazole. Among this group, 7 (50%) patients additionally received allopurinol, 1 patient underwent a prior surgical excision which resulted in the diagnosis, and 1 patient was treated with hyperbaric oxygen. Three (21.4%) patients were treated with local treatment alone: 2 (14.3%) with cryotherapy and wound care, and 1 case with simple wound care alone because of the shortage of pentavalent antimonials at that time. One patient was treated with cryotherapy and systemic allopurinol. The response was good in the majority of cases (n = 12; 85.7%), while it was unsatisfactory in 1 (7.1%) case. The ultimate outcome was unknown in 1 (7.1%) case. Summary of the treatment methods applied and the achieved outcomes is presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Treatment and outcomes in the studied group

Discussion

Leishmaniasis is not a notifiable disease in Poland despite the WHO recommendations [6, 10] and the suggestions of the European Centre for Diseases Prevention and Control experts [14], and therefore, the overall national incidence of the disease is unknown. Only few earlier case-reports of human CL at our center [15] or at other Polish centers [16–30] have ever been published. Thus, it may cautiously be assumed to our best knowledge that this series of 14 cases constitutes the great majority of CL cases diagnosed and treated in Poland in the recent 13 years.

The lack of epidemiological surveillance of leishmaniasis in Poland is disturbing, considering the recent influx of immigrants from CL-endemic high-burden countries such as Syria into the European Union [31–33], as well as the continuous expansion of the range of phlebotomine sandflies northwards in Europe as they are already established in Austria, Germany and Hungary – countries located along with Poland in Central Europe [34, 35].

The analyzed population, although small, is similar in sex and age to the other ones studied in Europe. The study also demonstrates a significant increase in the number of cases of imported CL, mainly in tourists, treated per year at our center over the last 5 years (Figure 1), which is consistent with the reports from the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Austria [36–40]. Poland is one of the top performers in Europe in terms of outbound tourism growth (+7% annually) [41], nevertheless, very little is known about the non-European destinations trending among Poles [42, 43]. Four (28.6%) patients were infected during work or military service abroad, which confirms the importance of CL as an occupational disease [44]. On the other hand, not a single case was diagnosed in immigrants or in people visiting friends or relatives (VFRs), which stands in contrast to countries such as Germany or Australia, where immigrants constitute a significant share in the total incidence of CL importation [33, 45].

Our earlier study demonstrated that the awareness of malaria and of the prophylaxis methods against it remains unsatisfactory among Polish travelers, and that some of them, especially those committed to ‘ecologic’ or ‘natural’ lifestyle, despise the prophylaxis methods as unnecessary or even noxious [46]; it may possibly be even more accurate in regard to the relatively lesser known leishmaniasis. The absence of any reimbursement by the national health insurance in Poland for the travel medicine services and for travel-related vaccinations or prophylactic drugs (with the exception of some antibiotics) further deters travelers, often young students interested in low-cost tourism, from seeking them.

Half of the patients at our institution were infected in the New World, which is similar to the British study [36] and significantly more than in the Dutch study [37]; this is probably due to the fact that the majority of our patients travelled for tourism, whereas roughly half of the patients in the Dutch series were military personnel (compared to 14.3% in our study and to 17% in the British study), and the majority of them served in Afghanistan [37, 47]. In the recent two decades, Polish military personnel have also served in high numbers in the Middle Eastern and Asian countries endemic for CL (Iraq, Afghanistan); however, in contrast to the British, the Dutch or the American servicemen deployed to the region, none of their Polish counterparts was diagnosed with CL [48, 49], and the only 2 soldiers included in our study served elsewhere: one in Belize, the site of a jungle training facility where soldiers of other nations have also been known to contract the disease [50, 51], and one in Chad on a peacekeeping mission. Such a discrepancy might raise doubts as to whether it was caused indeed by the lower rate of infection compared to soldiers of other nations serving in Iraq or Afghanistan or it was a result of underdiagnosing of Polish troops.

The time from the onset of symptoms to the correct diagnosis was relatively long in spite of the fact that the lesions among the vast majority of the analyzed patients had an appearance typical for CL (Figure 2); this reflects the problems highlighted in other studies, such as the popular misconception that leishmaniasis is a strictly tropical disease, in spite of the numerous cases acquired in Southern and South-Eastern Europe [52–65], the lack of awareness among clinicians (including dermatologists) in Poland, similar to other non-endemic-countries [37], as well as among travelers [66]. One could only speculate how many cases of the imported CL remain undiagnosed in Poland, particularly in cases with atypical appearance of lesions.

Figure 2

Ulceration of the right lower limb typical of CL in a 25-year-old male tourist who returned from Bolivia

The microscopic examination of the Giemsa stain was the mainstay of diagnosis up to 2009 at our institution, and the PCR was also used in the patients from that year onwards. The introduction of the PCR at our institution dramatically improved, like elsewhere [67–69], the sensitivity of diagnosis because as many as 6 (42.8%) of the presented cases had a positive PCR result for Leishmania spp. in spite of the negative Giemsa stain and, consequently, would have been prone to misdiagnosis in the situation of absence of the molecular test, especially in cases of atypical or longer-lasting lesions, as the sensitivity of the Giemsa stain paradoxically decreases with longer duration of the infection [1].

The percentage of patients in whom the causative species was identified was unsatisfactory in this study, considering the utmost importance of species determination for the choice of appropriate management, which has been emphasized in all the recent recommendations [8, 70, 71]. Unfortunately, the gene sequencer required for the species identification failed with time, and no new apparatus was obtained due to underfinancing of the laboratory. This reflects the broader problem in the healthcare system across Poland of inadequate financing of the laboratory services which tend to be targeted as one of the first by the austerity measures of the medical institutions; the expenses for laboratory diagnostics per capita are in Poland among the lowest in the European Union [72, 73].

The treatment methods used reflect partially the difficulties in obtaining appropriate medication to our institution at various times: numerous pivotal antileishmanial drugs (pentavalent antimonials, miltefosine, pentamidine, topical paromomycin or benzethonium chloride) neither are registered in Poland nor do they hold an European Union-wide approval, thus being available exclusively through a complicated official procedure of individual import authorization; moreover, a general shortage in pentavalent antimonials supply throughout the world has repeatedly occurred in the recent years. Of note, treatment of many cases in our study did not conform to the recommendations of the LeishMan European Working Group because the majority of the patients were treated before the recommendations were issued [70]. As the recommendations favor local management such as cryotherapy in many clinical situations, cooperation with an experienced dermatologist is crucial in the treatment process.

One of the more important shortcomings of this study is the inadequate follow-up, similar to other studies [8]. It is particularly true in regard to the patients infected in the New World, as people with the New World CL should be actively monitored by clinical appearance, including by performing a careful nasal and oropharyngeal examination periodically up to 1 year, or at least 2 years if at increased risk for mucosal involvement [40, 71, 74], and this kind of surveillance was not maintained for the patients at our institution.

Conclusions

We present the largest series of CL cases diagnosed and treated in Poland. Our study suggests that much remains to be undertaken in our country in terms of educating physicians, travelers, as well as of improving the access to travel medicine services and to the diagnosis and treatment methods appropriate for CL. No epidemiological data for leishmaniasis exist for Poland because of lack of epidemiological surveillance for the disease in the country; in our opinion, this situation needs to be altered, taking into account the geographic expansion of sandflies in Europe, the increasing influx of immigrants into the European Union, as well as the increasing popularity of tourism among Poles.