Introduction

Cardiovascular medicine at its beginning was dominated by surgical treatment options. The trend of the last decades is heading towards catheterization procedures. Alcohol septal ablation (ASA) was published by Sigwart in 1995 [1] whereas transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) was performed in 2002 for the first time [2]. Both methods have become efficient therapeutic options not only for patients not suitable for surgery but also for low-risk patients [3–5]. Although the procedures are widely performed, certain challenges remain [6, 7]. Moreover, as patients get older, new difficulties emerge.

We present a case of a patient with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) that was treated by ASA. Fifteen years later the patient developed severe aortic stenosis and was treated by TAVI that became severely stenotic 5 years later and required TAVI-in-TAVI implantation.

Case series

A 72-year-old woman presented to our outpatient clinic with shortness of breath as a main manifestation, heart failure New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III and nocturnal dyspnea. On the physical examination, the patient had rales heard over both lung bases, blood pressure was 130/70 mm Hg, heart rate was 70 beats/min with atrioventricular dual paced rhythm. The patient has an apple shape body habitus and short stature.

The patient has a history of HOCM, had a pacemaker implantation 30 years earlier and underwent ASA for left ventricular outflow tract obstruction 8 years afterwards. Moreover, she had symptomatic severe aortic stenosis 5 years ago. Based on the patient’s preference and high surgical risk TAVI was performed using a LOTUS 23 mm (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, USA). The patient was prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for 6 months followed by aspirin alone. On top of that, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation was detected and treated with amiodarone and rivaroxaban in addition to the treatment of heart failure.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35%, Lotus aortic valve gradients were 53/29 mm Hg, iAVA 0.55, the motion of the right coronary cusp was restricted, there was no aortic regurgitation, moderate mitral regurgitation and high probability of pulmonary hypertension with PASP above 50 mm Hg. Computed tomography (CT) of the heart showed calcification of the Lotus aortic valve, but there was no thrombosis or vegetation of the aortic valve.

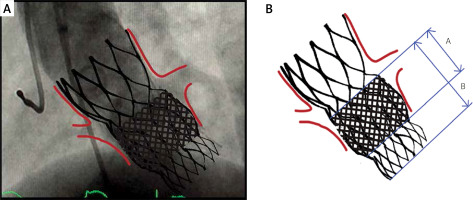

Due to comorbidities and high surgical risk, the heart team recommended a TAVI-in-TAVI procedure. Estimated EUROSCORE II and STS score were 8.4% and 8.8% respectively. TAVI-in-TAVI under general anesthesia with transfemoral access was performed. First, a 23-mm Portico valve [8] was inserted into the degenerated 23-mm Lotus valve. Then, post-dilatation with a 20 mm balloon was carried out. The whole procedure was thoroughly prepared as shown in Figures 1 A and B. The patient was able to walk on the evening after the procedure. Postprocedure transthoracic echocardiography showed a reduction of transaortic gradients to 16/8 mm Hg. After a 3-month follow-up the transaortic gradient stayed low and the patient’s functional NYHA class improved to II.

Figure 1

The stent frame of original Lotus valve was overlapping the coronary ostia. Therefore, the new valve had to be chosen very cautiously with regard to the index stent frame height. Since the height of 23-mm Lotus stent was 19 mm (A), the 23-mm Portico with nonflared anulus section height of 26 mm (B) was chosen

Discussion

This case shows a unique set of catheterization therapies performed over two decades. The patient underwent ASA. Years later she developed severe aortic stenosis and had TAVI which degenerated early and required TAVI-in-TAVI. Furthermore, we present a favorable early outcome of TAVI-in-TAVI 23-mm Portico into a 23-mm Lotus valve. On one hand, the TAVI-in-TAVI procedure provides an important way to avoid high-risk surgery once the TAVI valve becomes degenerated [9]. On the other hand, it brings brand new challenges that we will need to cope with in the future. As patients with TAVI are younger and have a longer estimated lifespan, the need for safe coronary access becomes more pressing as the manifestation of coronary artery disease is more expectable. Also, occlusion of coronary ostia becomes a serious issue in redo TAVI procedures. The complexity of the procedure is a consequence of the anatomical and device related factors [6]. The preparation and implantation have to be done with great accuracy and precision. The stent frame of the original Lotus valve was overlapping the coronary ostia. The free flow to coronary arteries was ensured by side access outside the prosthetic stent owing to the high and wide sino-tubular junction. Therefore, the new valve had to be chosen very cautiously with regard to the index stent frame height. Since the height of the 23-mm Lotus stent was 19 mm, the 23-mm Portico with nonflared anulus section height of 26 mm was chosen. Moreover, caution had to be taken regarding the depth of implantation, as the restriction of anterior mitral valve movement was feared.

Conclusions

This case is an evident example of an ongoing paradigm shift towards catheterization procedures in cardiovascular medicine. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, we describe the first case of TAVI-in-TAVI 23-mm Portico into 23-mm Lotus valve implantation. We have proven the clinical utility and technical feasibility of this procedure. We would like to stress the importance of exact and precise preprocedural preparation.