INTRODUCTION

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a rare angioproliferative neoplasm originating from the endothelial cell lineage associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8, also known as KS-associated herpesvirus) [1]. Over 95% of lesions, regardless of clinical subtype, have been found to be associated with HHV-8 [1]. There are four wellestablished clinical variants of KS: classic, endemic (African), iatrogenic (transplant-associated), and epidemic (AIDS-associated) [2]. A fifth variant has been described in men who have sex with men (MSM) without human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [3].

OBJECTIVE

We present a rare case of a patient with classic Kaposi sarcoma (CKS) who experienced spontaneous remission of the lesions. The clinical course of the disease makes it challenging to determine whether it represents the classic or an iatrogenic variant potentially triggered by glucocorticosteroid use.

CASE REPORT

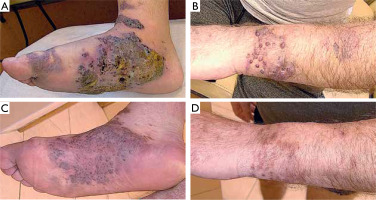

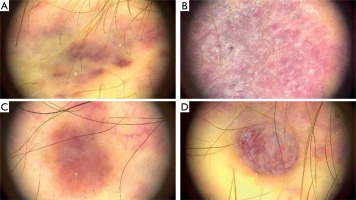

A 63-year-old Polish male, non-MSM, presented with macular, plaque, and nodular lesions with a vascular-like appearance on the forearms, feet, thighs, and hands, present for 6 months (figs. 1 A, B). The initial lesions appeared on the feet and gradually increased in size and intensity. Subsequently, lesions developed on his left forearm. Dermatoscopic examination revealed blue-red areas, white shiny lines, white clods, and polychromatic zones (fig. 2).

Figure 2

Morphological changes of the skin revealed by dermoscopic examination: A – blue-red area, B – white shiny lines, C – white clods, D – polychromatic color areas

The patient’s medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), and a history of acute pancreatitis. He had not received immunosuppressive therapy prior to disease onset; however, he began taking dexamethasone 3 months after the appearance of the skin lesions, starting at a dose of 12 mg/day with gradual tapering due to ITP. Glucocorticosteroid therapy therefore may have contributed to disease progression.

Physical examination revealed edema of the lower legs and feet, as well as enlarged inguinal lymph nodes on the left side. Laboratory tests showed elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, along with thrombocytopenia and leukopenia. Two separate HIV tests were negative. Skin biopsy revealed proliferating spindleshaped tumor cells forming vascular slits filled with erythrocytes. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for ERG, CD31, HHV-8, and Ki-67 (25% of cells).

To assess the stage of the disease, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed revealing renal infiltrative changes and alterations associated with a history of acute pancreatitis, including occlusion of the splenic vein, splenomegaly and developed venous collateral circulation. A chest CT scan revealed mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy, scattered fibroatelectatic bands with micronodules causing traction bronchiectasis in both lungs, and discrete areas of ground-glass opacity.

Due to disseminated skin lesions with rapid progression and accompanying inguinal and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as renal infiltration, the patient was referred to an oncology center for further systemic therapy. The patient discontinued dermatological follow-up and returned after 9 months. Physical examination revealed significant remission of the skin lesions (figs. 1 C, D). According to the patient, the oncologist disqualified him from systemic treatment. He denied using any topical or systemic medications that might have influenced the course of the disease. However, he had discontinued steroid therapy 3 months earlier, which may have contributed to lesion regression.

A follow-up chest CT was ordered to assess whether internal organ involvement had also regressed. Unfortunately, further evaluation was not possible, as the patient died from sepsis 2 months later.

DISCUSSION

CKS is an indolent disease that most frequently occurs on the lower extremities of men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, or Middle Eastern descent, and less commonly occurs in Northern Europe and North America [4]. It predominantly affects elderly males, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 10 : 1 [5]. Presented patient was not of Mediterranean descent.

There is a lack of reliable data on the epidemiology of KS in Poland. Available reports do not differentiate between the subtypes of KS. According to information from the Polish National Cancer Registry, in 2021, 20 men and 8 women were diagnosed with KS, accounting for 0.02% and 0.01% of all cancers, respectively. Incidence increases with age and peaks in the sixth and seventh decades of life for both sexes. The annual incidence rate is 0.07 per 100,000 people [6].

Patients with KS are at increased risk for solid organ malignancies, Hodgkin lymphoma and acute lymphocytic lymphoma. Additionally, KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman disease, plasmablastic lymphoma, and primary effusion lymphoma occur more frequently in individuals with KS [4].

CKS is characterized by the occurrence of papules and purple nodules predominantly on the lower limbs, often associated with lymphoedema [5]. In the presented case, lesions initially appeared on the lower extremities, which remained the most severely affected areas throughout the observation period. KSHV is necessary but not sufficient for the development of all forms of KS. Seroconversion usually occurs via salivary transmission but may also result from blood exposure or sexual contact. Factors influencing tumorigenesis include hypoxia, oxidative stress, viral coinfection, epigenetic modification, immune suppression, and hyperglycemia [4].

The histopathological appearance of the disease is consistent across all subtypes. Histologically, KS is characterized by neoangiogenesis, proliferating spindle-shaped tumor cells, lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltration, incomplete vascular slit formation, and extravascular hemorrhage. These features are most prominent in nodular and plaque lesions, whereas macular lesions may resemble inflammatory dermatoses. Rare histopathological variants of KS have also been described [2].

CKS typically has a favorable prognosis, with a low mortality rate directly attributable to the disease [7]. It is generally slow-growing and often does not require specific treatment. Therapeutic options include chemotherapy, immunomodulatory agents, and immune stimulation [5]. In many cases, close observation is the most appropriate management strategy. Cases of spontaneous remission have been reported in iatrogenic KS following discontinuation of corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents, and in AIDS-associated KS after the initiation of antiretroviral therapy. The literature also includes isolated cases of spontaneous remission in the classic form [8, 9].

In more disseminated forms of the disease, singleagent chemotherapy may be considered, with vinblastine or bleomycin as preferred options. In cases of treatment failure or when KS brings a functional or life-threatening risk, liposomal anthracyclines or taxanes may be used. Interferon, administered at doses of 3 to 5 million units, is generally well tolerated and may be an alternative to chemotherapy [5].

Treatment methods of CKS also include laser therapy, radiation therapy, brachytherapy, doxorubicin, interferon-a, vinblastine, vincristine, diphencyprone, imiquimod, rapamycin, silver nitrate, timolol, valganciclovir, IM immunoglobulin, pazopanib, pembrolizumab, pomalidomide, and thalidomide [4].

In the presented case, no other treatment was identified that could explain the observed remission. The role of glucocorticosteroids in influencing the clinical course remains uncertain. The patient received steroid therapy for 8 months, starting 3 months after the initial appearance of lesions and ending 3 months prior to the follow-up visit.

Although the iatrogenic variant of KS is typically associated with immunosuppressive drugs, it is also known that glucocorticosteroids increase the risk of developing CKS [10] and worsen outcomes in HIV-associated KS [11]. The remission observed in this case may have been due to an initial exacerbation of the disease under steroid therapy, followed by improvement after its discontinuation, or it may represent a true spontaneous remission of CKS, which is extremely rare [8, 9].

A limitation of this report is the lack of histopathological confirmation of mediastinal lymph node involvement, which prevents exclusion of a coexisting systemic disease. Additionally, no follow-up CT scan was available to determine whether internal organ involvement had resolved. The relationship between the patient’s death and KS remains unclear.

CONCLUSIONS

Among the five known variants of KS, it is usually possible to identify the subtype responsible for the disease in a given patient. In the case described, the patient experienced spontaneous remission of skin lesions without treatment. We believe the patient suffered from CKS, which was exacerbated by glucocorticosteroid therapy administered during the course of the disease. The observed remission was likely related to the discontinuation of steroid therapy. It is significant to emphasize that glucocorticosteroids can worsen the clinical course of KS.