Introduction

Compared to other areas of medicine, there is great potential for the use of modern technologies, such as online distance consultations, initial diagnostics via telephone and computer applications, and artificial intelligence (AI)-based support for doctors in dermatology [1]. AI systems can be integrated in highly-specialized software dedicated to specific fields of medicine [2] as well as easy-to-use applications for mobile devices.

The use of technologies that facilitate remote consultations, or even replace a real doctor, offers great hope for improving the functioning of the healthcare system. In critical situations, these technologies can relieve medical personnel and release reserves for urgent tasks.

However, the effective implementation of these modern technologies requires acceptance of both patients and medical staff. Such acceptance is influenced by the perceived importance of these technologies and the degree of trust in them by their users.

Aim

The present study surveys the opinions on the use of modern technologies, such as telemedicine and artificial intelligence in medicine, and the level of trust in them, among medical personnel specializing in dermatology and venereology.

Material and methods

A paper questionnaire comprising 16 questions was used for the study. The questionnaire was developed specifically for this purpose. The first three questions concerned the sex, age and specialization of the doctor. The next two concerned their knowledge of concepts such as telemedicine and the ability to use medical applications. The remaining questions concerned opinions on issues related to telemedicine and artificial intelligence in medicine. The questionnaires were distributed to qualified specialists in dermatology, or individuals undergoing training in dermatology and venereology.

The study was performed mainly during a dermatological conference in May 2019, i.e. before the pandemic time. Recruitment took place by snowball sampling: the respondents passed the questionnaires to other people who met the criteria for participating in the study. In total, 140 questionnaires were obtained. Of these, incorrectly completed forms (n = 19) were excluded, and so were surveys completed by persons not involved in dermatology (n = 8), and those filled in by people unfamiliar with telemedicine, indicated by a negative answer to question 4 (n = 23). In the disqualified group of 23 participants, no statistical correlation was found between age, professional status and negative answer to question 4.

Eventually, 90 dermatologists and dermatology trainees were subjected to statistical analysis. The collected data were analysed using non-parametric tests. The Pearson’s χ2 test was used to confirm independence. Hypotheses that the test statistic did not allow to be considered statistically significant were omitted.

Results

The detailed results of the questionnaire performed are presented in Table 1. The majority of participants (n = 78/90) were women. Due to the low number of men, no comparison was possible between sex of the respondent and particular answer.

Table 1

Opinion on modern technologies in medicine

Almost half of the examined group (n = 43/90) were people aged between 25–34 years. The rest were aged over 34 years. The mean age of the study participants was 41 years. In total, 47 respondents were qualified specialists in dermatology and venereology, while the remaining 43 were still undergoing training in this field. Eighteen respondents have given medical consultations in the form of video conferencing or online chats, now or in the past. 23 doctors answered they had never had any contact with such solutions and never heard about them (Question 4 – Q.4). As previously mentioned, they were not included in the final study group of 90 participants. In addition, 75 respondents reported having contact with mobile medical applications on smartphones or tablets, mainly for educational purposes (Q5).

Some of the respondents (18 people) agreed that online medical consultations, in the form of videoconferences or chats, could replace a visit to the doctor’s office, but only three of them claimed “definitely yes”. Most respondents were sceptical: 70 gave negative responses, with 26 indicating “definitely not” (Q6).

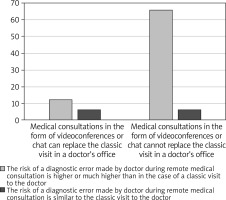

Thirty-one participants believed that the risk of a mistake by a doctor was definitely higher during a medical consultation given in the form of a video conference or chat than in the case of a classic doctor’s visit. In addition, 49 participants rated this risk as “higher” and 10 considered it to be similar (Q7).

Concerning the issue of the role of the modern information systems in the future (Q8), seven respondents agreed that they would become the most important tool in diagnosis and treatment. Six respondents think that they will prove to be useless but seventy-six believed they would perform an auxiliary function in diagnosis and treatment.

The next question (Q9) addressed what the respondents believed to be the greatest threat associated with the use of such technologies in medicine. A maximum of two answers to this question were allowed. The most frequently indicated response was the risk of excessive trust in such technologies by doctors and patients (49 respondents). This was followed by the risk of life-threatening errors made by these systems and devices (46 respondents), the risk of leakage and unauthorized use of sensitive patient data, and the risk of more difficult access to traditional medical advice due to the reduction in the number of consulting specialists.

Regarding whether the implementation of artificial intelligence and other modern medical technologies would improve medical standards (Q10), 64 affirmative answers were given, including 13 “definitely yes” and 28 negative answers, including three “definitely no”.

However, half of the respondents believed that technologies such as AI could reduce the number of medical errors, while the other half did not (Q11). In addition, most respondents indicated that new technologies such as AI will not replace health providers in the nearest 20 years but will increase the skills of medical staff (59 doctors) (Q12). Twenty-seven respondents agreed that doctors of any specialization could be replaced by IT systems such as AI, with six indicating “definitely yes”. In contrast, 63 returned negative answers, including 24 as “definitely not” (Q13).

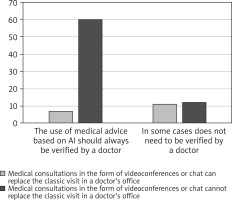

Regarding the verification of advice provided on the basis of AI, 67 respondents believed that such advice should always be verified by a physician, while the remaining 23 believed that it is necessary only in selected cases. None of the 90 participants decided that such advice can replace medical advice in all cases without any verification (Q14).

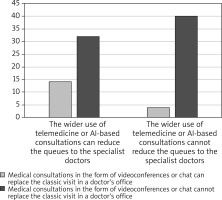

Regarding the areas of medicine where the implementation of AI technologies would be the most profitable, the most frequently-chosen answers were disease prevention and promotion of a healthy lifestyle (n = 68), followed by education (n = 56), diagnosis (n = 42) and management of the healthcare system (n = 32). Finally, while roughly half the respondents (n = 46) indicated that the wider use of telemedicine and consultations based on AI may contribute to reducing queues to specialists, half (n = 44) believed that it was not the case.

Respondents who tended to indicate that AI could not reduce queues to doctors also tended to indicate that telemedicine could not replace a classic visit to a doctor. Those who claimed they can reduce the queues were more divided in opinions concerning question 6, but majority of them also indicated that telemedicine consultations mentioned could not replace the classic visit to a doctor’s office (Figure 1).

The majority of those who claimed classic visits could not be replaced by remote consultations believed that all diagnoses made by AI should be verified by doctors (Figure 2).

Both the respondents claiming telemedicine could replace classic visits and those do not indicated that remote consultations are associated with a higher risk of medical error than a classic visit (Figure 3).

Most respondents who did not believe that technologies such as AI could replace medical workers or even increase their skills in the next 20 years also doubt they could replace doctors of any specialization in the future (Figure 4).

The respondents who agreed that the implementation of AI and other modern technologies in medicine may reduce the number of medical errors also tend to claim such technology would also raise medical standards. Those who do not tended also to claim that their implementation would not help reduce medical errors.

Surprisingly, of the five respondents did not believe that AI could replace doctors, one had never used a mobile medical application. In addition, two respondents who had never used such applications believed that doctors of some specialties could be replaced by AI.

Discussion

Over the last 20 years, there has been a tremendous progress in the field of medical science, particularly concerning in the way diseases are diagnosed and treated. Such progress is linked to the emergence of new technologies as part of the data revolution. Many researchers have hailed “the coming of age of artificial intelligence in medicine” [3].

The use of large digital data sets and the growth in computing power has allowed the widespread application of AI: a type of machine learning that can process large amounts of data, solve problems, make decisions, and has the ability to learn independently [4]. Recent years have seen the growth of AI in medicine. Recent developments in computer science have raised expectations that automated diagnostic systems will become available to help physicians in the diagnostic process. The body of medical data is constantly increasing; however, it needs to be properly structured to train AI algorithms [5]. Big data is well supported by practically endless storage in the cloud, and learning algorithms are becoming more accurate and perfect as they interact with training data, allowing novel insights into diagnostic, treatment options, and patient outcomes.

Dermatology is a visual specialty and clinical imaging is now considered to be an essential part of documentation and follow up. Nowadays more than 800 mobile dermatology applications are used by patients, medical students and sometimes physicians [6].

However, some scientific publications suggest that AI could be equal or even better at diagnosing skin cancers, mainly melanoma, than qualified dermatologists. However, the value of popular smartphone applications for diagnosing popular skin diseases is poorly understood [7]. Moreover, teledermatology services such as remote patient visits are of considerable significance when medical visits are not possible. However, it remains a point of contention whether such systems work, whether it helps and most of all, whether such systems are understood and generally accepted among health providers, such as dermatologists.

An important factor in the popularization of AI and remote medical advice in medicine, and their level of safety, is the opinion of the medical community regarding their possible benefits. However, little is known of the opinion of Polish dermatologists in this regard: only about 80% (90/113) of dermatologists in the present study were at least slightly familiar with the issue of remote consultations, while 92% of the Polish population have heard about AI, and a quarter have had direct contact with it [8].

The study group were quite acquainted with the use of modern technologies in their everyday practice. Approximately 16%, i.e. 18 out of 113 respondents, had personal contact with telemedicine (Q4), and the vast majority used different mobile medical applications (Apps) on a daily basis (Q5; 75 out of 90 participants). Interestingly, most of the listed Apps were connected with educational purposes. Although health-related Apps play a growing role in the management of illnesses in the field of internal medicine [9], medical personnel must be aware of their benefits and limitations and their medical studies should prepare them in this regard. More importantly, most of the medical Apps dedicated to physicians and patients are not validated and their usefulness has been never assessed. Studies have indicated the need for improvements in mobile dermatology Apps intended for education [10].

AI is most commonly used in everyday life by people aged 18–24, and this age group is the most likely to predict the continuing development of AI in the coming years [8]. However, in the present study, no statistical correlation was found between specific answers and age group (i.e. 25–34 and 35 and above) and the level of education (specialisation). This might be connected with the specific group of responders, these being dermatologists with a high level of education. It is important to note that the study participants were mainly recruited during a scientific conference, where most of the population are open to new things; as such, despite the age group, only 15 out of 90 people (Q5) had never used any mobile medical application. Most of them do. The medical Apps used by most of the dermatologists were connected with education (Q5).

Teledermatology has become an increasingly used medium for delivering dermatology services. Our findings (Q16) confirm those of previous studies that providing remote consultations to health care systems can reduce general costs and improve patient access by shortening waiting times [11]. Since the completion of our study, telemedicine has progressed rapidly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The present study included only dermatologists who have given telemedicine consultations in the past or have heard about them, regardless of their knowledge of new technologies in medicine. About 20% (23 among 113 dermatologists) had never heard about such technologies, compared to 56.5% of the general Polish population in 2017, as indicated by BIOSTAT [12]. Among dermatologists who had acquaintance with teledermatology, almost half of them were sceptical and claimed that such visit cannot replace the classic visit (Q6; 44/90) and is connected with a higher or much higher risk of diagnostic error (Q7; 80/90). In our opinion remote visits are useful only in chronic skin disorders, mainly in previously known patients. Very few dermatological diseases can be easily diagnosed based only on clinical photographs and medical interview, such as contact dermatitis, urticaria, impetigo contagiosa or insect bites.

Literature data indicated that modern technologies in medicine do not replace physicians but rather improve their knowledge and skills and facilitate their work [13], as confirmed by 59 out of 90 participants in Q12 of the present study. In addition, 63/90 believed it to be impossible to replace doctors of any specialization, even in the future (Q13). The majority of our respondents indicated that AI will play an auxiliary role in diagnosis and treatment (Q8; 76/90), while one third of the Polish population believe that AI will positively contribute to the development of medicine [8].

Many authors recommend that physicians should learn how modern technologies work in healthcare, but at the same time companies such as IBM should increase awareness in the general public about the advantages and risks of using AI in medicine [14]. Our respondents believed there to be a high risk of life-threatening mistakes by AI systems (Q9; 46/90) and that all diagnoses should be verified by a doctor (Q14). Nevertheless, they believe that the implementation of AI in medicine may contribute to the improvement of medical standards (“definitely yes” and “rather yes” indicated by 64 out of 90 in Q10).

The fears regarding the errors associated with AI are reasonable ones. Therefore, there is a need to raise awareness of this technology among medical specialists.

The prevailing view among the surveyed Polish dermatologists was that new information technologies appear to be most useful in disease prevention, promotion of a healthy lifestyle and education, but less so in the diagnostic process and disease management (Q15). Respondents who were enthusiastic about replacing conventional visits to the doctor’s office with remote advice (telemedicine) appear to see the potential benefits of implementing AI but remain sceptical about the accuracy of AI diagnoses. This may be due to the human supervision that still exists in telemedicine, but which is absent when the patient entrusts his/her health to the machine.

In our opinion, patients and physicians would prefer a healthcare system with human workers performing duties such as medical interview and examination, and who are supported by computers that can collect, filter, and analyse large amounts of complex data. These two sets of duties are usually complementary.

It should be noted that the study was conducted shortly prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is possible that the views of both doctors and patients on the legitimacy of telemedicine may have changed. However, the pandemic has been accompanied by the rise of a COVID “infodemic”, i.e. an excessive amount of information and misinformation on the subject, which can undermine trust in new technology.

Conclusions

Nowadays there are many uses of artificial intelligence in medicine. These methods excel at automatically recognizing complex patterns in imaging data and can be useful in many areas such as dermatology, radiology, pathomorphology and many others. For example it can assist in technically challenging tasks like screening mammography interpretation, diagnosing skin lesions etc. where it can detect characteristics well beyond those considered by humans. In pathology, AI is able to perform mitosis detection, segment histologic primitives (such as nuclei, tubules and epithelium), and characterize and classify tissue [15]. In dermatology, AI shows high efficiency in the classification of skin lesions and distinguishing the malignant ones from others [16]. The number of applications dedicated to patients themselves is also constantly growing. Among the huge number of dermatological applications that differ in advancement, there are those that allow patients to monitor the appearance of skin changes and even pre-diagnose them, but still there is little reliable data on their effectiveness.

Although the coming years will bring the strong cooperation between physicians and digital systems, it is unlikely that automation, either a robot or an algorithm, will take the place of a doctor.