Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a worldwide pandemic. After the lockdown to limit SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus infection, education worldwide, including academic activity, abruptly transitioned to digital education [1]. Changes in psychosocial factors, changes in residency, and increased time demands from activities such as work and school all contributed to a decrease in physical activity (PA) levels and frequency across the university student life cycle [2,3].

Most studies report a significant decline in PA levels during the pandemic across all age groups and genders [4-7]. Both self-reported and device-based measurements indicate a reduction in PA, although not all age groups showed statistically significant changes [4]. Studies were reporting higher sedentary behavior levels during the pandemic [6]. The COVID-19 pandemic has also led to a significant decrease in PA levels and an increase in sedentary behavior among university students [8,9]. This trend was observed across various countries and was more pronounced in male students [9,10]. Students who were more physically active before the pandemic generally continued to meet minimum PA recommendations, although their PA levels still decreased [8,11]. However, other factors associated with physical inactivity, such as biological and psychological aspects [12,13], fear of injury, illness, and even death, have been identified as some of the most common barriers to PA [14,15].

The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) and its subsequent versions, PAR-Q+ and ePARmed-X+, are essential tools for pre-participation screening in physical activity [16,17]. PAR-Q is a commonly utilized tool intended to assess individuals for possible health risks before participating in PA. It seeks to guarantee that participants can engage in exercise programs safely. PAR-Q is reliable, evidence-based, and has been improved to remove physical activity barriers, as well as having high internal consistency and reproducibility, allowing for safe and beneficial physical activity in a diverse range of populations [14,16]. PA readiness is a multifaceted concept that encompasses both physical and psychological dimensions. PA readiness is composed of four dimensions: vitality, physical fatigue, discomfort, and health [18]. Age, gender, marital status, educational level, and health status all have an impact on PA readiness. Younger age, being male, being married, and having higher education levels are associated with higher PA readiness [19,20].

Many studies have examined the decline of PA during the pandemic, but not many have examined the intervariable relationships and motivational factors affecting Slovakian university students’ physical activity. University students in Slovakia reported a significant decline in PA levels during the pandemic, with 21% reporting minimal to no exercise [21]. Exercise frequency also correlated with improved health and well-being, suggesting that physical activity may be motivated by perceived health benefits. Male students participated in PA more often and more intensely than female students, according to a regional study [22]. According to the same study, male students reported an 80% higher weekly average of MET-minutes in moderate-intensity activities compared to female students.

Students in various academic programs face unique challenges in maintaining adequate levels of PA, which are heavily influenced by their specific field of study, lifestyle, and academic demands. Students in technical study programs frequently face high cardiovascular risks as a result of their sedentary behavior and academic workload [23]. According to the study, while the majority of participants engaged in moderate PA, a significant proportion of students exhibited sedentary tendencies and needed professional medical consultations before safely increasing their PA levels. Despite being more aware of healthy lifestyle practices, medical students frequently struggle to maintain regular PA due to the high academic pressures they face [24]. A cross-sectional study of medical students in India found that only 26.7% maintained a consistent physical exercise routine, with a large proportion of students engaging in sedentary behavior. This, combined with higher stress levels, increased medical students’ risk for conditions such as hypertension and cardiovascular disease despite their awareness of the risks. In contrast, students in social science programs have lower levels of PA but report better mental health outcomes [25]. A study in Croatia comparing physiotherapy and social science students discovered that while physiotherapy students had higher PA scores, they also reported higher rates of musculoskeletal pain, which was most likely due to their physically demanding academic requirements. Social science students, on the other hand, reported lower levels of PA but better mental health and less musculoskeletal pain, indicating the distinct physical and mental health challenges that students in these disciplines face.

Aim of the work

This study aims to examine the relationship between the prevalence of self-reported various health issues, which may indicate reduced PA readiness and contribute to a comprehensive understanding of PA barriers during and after pandemic restrictions while exploring the differences in these health conditions between students from different universities to identify if institutional factors may contribute to variations in health outcomes.

Material and methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study is part of the research task of VEGA project No. 1/0234/22, “The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on readiness and organism reaction of university students to physical load”. The research sample consisted of 1,135 students (19.51±1.74 years) of the University of Pavol Jozef Šafárik in Košice (UPJŠ) and Technical University in Košice (TUKE). UPJŠ is a comprehensive university with a strong emphasis on natural sciences, social sciences, humanities, and medical sciences. Its programs are oriented toward fields such as medicine, law, public administration, psychology, and natural sciences (including biology, chemistry, and physics). TUKE is a specialized institution with a primary focus on technical and engineering disciplines. Its study programs are oriented toward fields such as engineering, information technology, architecture, aviation, and applied sciences like materials science.

The sample of students included 586 males (19.29±1.88 years) and 549 females (19.74±1.55 years) who chose the elective course Physical Education (PE) as part of their studies. We have provided a more detailed description of the participants in Table 1.

Procedure

All students provided written consent to participate. In this study, we used a modified and translated version of the original PAR-Q [16]. This adapted version assessed the health status of the students. The questionnaire included items on specific health conditions and risks, covering the following areas: 1) Heart Problems, 2) Chest (Heart) Pain, 3) Occurrence of Dizziness, 4) High Blood Pressure, 5) Diabetes, 6) Asthma, 7) Joint Problems, 8) Recent Colds, 9) Prohibited High-Intensity Activity, and 10) Heart Problems in the Family. The questionnaire also included two questions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. We investigated the frequency of PA before the pandemic and the subjective assessment of the impact of the pandemic on the frequency of PA after the pandemic.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using R Studio (version 2024.04.2), with chi-squared tests and Fisher’s exact tests to assess the associations between various health issues and participant characteristics, such as gender and university affiliation. Chi-squared tests were used where all assumptions were met, while Fisher’s exact test was applied in cases where expected cell counts were too low. The primary analyses compared the prevalence of positive responses to the health-related questions in the PAR-Q questionnaire between universities (UPJŠ vs. TUKE) and genders (male vs. female). For each health condition, a contingency table was created to examine the frequency distributions. A logistic regression analysis was performed to predict the impact of the pandemic on PA (dependent variable: “Pandemic Effect on PA”), with health conditions (e.g. heart issues, dizziness), gender, and university affiliation as predictors. The logistic regression results were reported with odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values, highlighting significant predictors of reduced PA during the pandemic. Statistical significance was determined at p<0.05. All analyses were two-tailed, and p-values were rounded to three decimal places for reporting consistency.

Results

The analysis of PAR-Q responses revealed significant health differences between UPJŠ and TUKE students, as well as between genders. Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview. A significant difference was found in the responses to the question regarding chest pain among females, where 20.20% of TUKE females reported chest pain compared to 12.90% of UPJŠ females (p<0.001). Among males, the prevalence of chest pain was 5.40% at TUKE and 4.50% at UPJŠ, which was not statistically significant. Female students from both universities reported a significantly higher prevalence of dizziness compared to their male counterparts. At TUKE, 23.20% of females reported dizziness (p<0.001) versus 4.40% of males. Similarly, at UPJŠ, 22.00% of females reported dizziness (p<0.001), while only 4.00% of males did. Among the female UPJŠ students, 15.30% reported a family history of heart problems, which was significantly higher than that of the male UPJŠ students (14.00%; p=0.004). No significant differences were observed between male (7.50%) and female (15.20%) TUKE students.

Table 2

Prevalence of positive responses to the PAR-Q questions by university, gender, and question

Female students of TUKE reported significantly more recent colds (51.50%) compared to female students of UPJŠ (49.10%; p=0.015). In contrast, recent colds were reported by 40.90% of male students from TUKE and 44.50% of male students from UPJŠ, but these differences were not statistically significant. No statistically significant differences were observed between groups for high blood pressure, diabetes, asthma, or joint problems. Although some differences in frequencies were noted, none reached the statistical significance threshold.

The distribution of positive responses from the PAR-Q indicated notable differences between universities and genders (Table 3). The comparison of health-related positive responses between universities UPJŠ and TUKE revealed a significant difference for students reporting one positive response. A Fisher’s exact test showed that TUKE students were significantly more likely to report one health-related issue compared to UPJŠ students (p=0.019). Specifically, 170 students from TUKE reported one positive response compared to 223 students from UPJŠ. This suggests that TUKE students may be more likely to experience or report a single health concern. For other numbers of positive responses (0, 2, 3, and higher), no significant differences were found between universities (all p>0.05). This indicates that the overall health profiles of students from UPJŠ and TUKE are generally similar, except at the level of reporting exactly one health concern.

Table 3

Total number of positive responses to the PAR-Q questions by university and gender

When comparing genders, Fisher’s exact test revealed statistically significant differences for 0, 1, and 2 positive responses. Male students were significantly more likely than female students to report no health-related issues (p=0.004). Male students were also significantly more likely than female students to report exactly one health issue (p=0.002). A similar trend was observed for two positive responses, where male students were more likely to report two health-related concerns (p=0.022). For higher numbers of positive responses (3 and above), no statistically significant differences were found between male and female students, suggesting that more severe health concerns (multiple issues) are similarly distributed across genders.

The frequency of PA before the pandemic showed significant differences between universities (Table 4). TUKE students were more active than UPJŠ students, with 44% of TUKE students engaging in PA at least three times a week, while UPJŠ students reported higher rates of participation in PA at least once a week. A chi-square test revealed a significant difference in the distribution of pre-pandemic PA levels between the two universities (X2(5, N=1135) = 12.356, p=0.030). Gender differences were even more pronounced, with 43% of females reporting higher levels of pre-pandemic PA compared to males. The gender differences were significant, as confirmed by the chi-square test (χ2(5) = 43.817, p<0.001).

Table 4

Self-reported frequency of pre-pandemic PA levels by gender and university

Students reported significant changes in their level of PA due to the pandemic (Table 5). Male students from TUKE maintained their pre-pandemic PA levels at a higher rate than male students from UPJŠ, with 42.49 % of TUKE males reporting no change in activity levels during the pandemic. In contrast, UPJŠ males showed higher levels of physical inactivity (25% became physically inactive). A chi-square test indicated significant differences in the pandemic impact on PA between the two universities (χ2(5) = 45.925, p<0.001). Similarly, gender differences in the pandemic impact on PA were significant (χ2(5) = 14.774, p=0.011), with a higher percentage of females reporting changes in their PA levels due to the pandemic.

Table 5

Self-reported impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the frequency of PA after the COVID-19 pandemic by gender and university

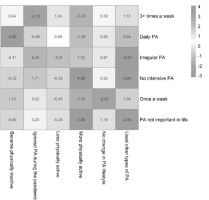

A chi-square test was performed to assess the association between pre-pandemic PA levels and changes in activity during the pandemic. The analysis showed a significant association (χ2(25) = 76.18, p<0.001), indicating that students’ pre-pandemic activity levels were related to how their activity changed due to the pandemic. There was a notable shift toward more passive activity patterns, with fewer participants reporting regular exercise.

A post-hoc analysis of standardized residuals revealed specific pre-pandemic and pandemic PA categories that contributed most to the chi-square result (Figure 1). The strongest positive residual was observed between “No intensive pre-pandemic PA” and “More physically active during the pandemic” (standardized residual = 4.09), indicating that participants who were previously inactive were more likely to become active during the pandemic. Conversely, “Irregular PA pre-pandemic” and “Used other types of PA during the pandemic” had the strongest negative residual (standardized residual = −3.15), indicating that those with irregular pre-pandemic activity were less likely to use alternative physical activities during the pandemic.

To better understand the factors influencing changes in PA during the pandemic, a logistic regression analysis was conducted (Table 6). The model included health conditions, gender, and university affiliation as predictors. The logistic regression model explained 8.5% of the variance in PA changes (McFadden’s pseudo R-squared = 0.085) with moderate classification accuracy (AUC=0.739).

Table 6

Logistic regression analysis of predictors influencing physical activity maintenance or increase among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic

[i] Notes: β = regression coefficient; SE Coef = standard error of the coefficient; Z = Z-value (standard normal distribution); p = p-value; χ2 = Chi-Square statistic; Odds ratio = exponentiated β, representing the odds of maintaining or increasing physical activity during the pandemic; statistically significant in bold (p<0.05).

University affiliation was a significant predictor, with students from UPJŠ being significantly more likely to maintain or increase their PA during the pandemic compared to those from TUKE (β=1.465, p=0.005). The odds of maintaining or increasing PA were 4.33 times higher for students from UPJŠ compared to TUKE.

Gender was marginally significant, with female students showing a higher likelihood of maintaining or increasing their PA compared to males (β=0.691, p=0.078). None of the health-related variables from the PAR-Q (e.g. heart issues, dizziness, asthma) were statistically significant predictors of pandemic-related PA changes. This suggests that these health factors did not have a strong impact on student’s ability to maintain or increase PA during the pandemic.

Discussion

COVID-19 caused a decrease in PA among college students by upsetting their daily routines. During this time, our study looked at how changes in PA were influenced by gender, university affiliation, and health conditions.

Female students reported significantly higher rates of dizziness (p<0.001) and chest pain (p<0.001) compared to their male counterparts. The presence of health barriers, particularly dizziness and chest pain, most likely reduced female students’ PA readiness, making it more difficult for them to participate in regular PA. The physical discomfort caused by these conditions, combined with potential psychological barriers, such as fear of exacerbating symptoms, may have contributed to lower activity levels. Previous studies have also found that women are more likely to report dizziness and chest pain, which are frequently associated with both physical and mental health issues. A complex interplay of hormonal, psychological, and behavioral factors influences women’s increased reporting of symptoms such as dizziness and chest pain, with health-seeking behavior and awareness adding to these gender differences. A study found that women experiencing acute myocardial infarction (AMI) have higher rates of dizziness and nausea, as well as more frequent reports of non-cardiac chest pain than men. This finding suggests that dizziness in women may be linked to broader physiological or psychological processes, as well as cardiovascular events [26]. Another study discovered that anxiety was strongly associated with dizziness in menopausal women, emphasizing the intersection of hormonal changes and mental health as contributing to these symptoms [27]. Furthermore, psychological factors, such as stress and anxiety, have been shown to play an important role in the higher frequency of reported chest pain in women, even in the absence of coronary heart disease [28]. Female students, especially at UPJŠ, are more likely to experience dizziness and chest pain, suggesting a gender-specific vulnerability to health barriers that limit PA. UPJŠ students have significantly higher rates of family heart issues than TUKE students (p<0.01), likely due to socioeconomic and environmental factors. UPJŠ, with its focus on humanities and social sciences, may experience higher psychosocial stress, which is known to contribute to cardiovascular risk [29]. TUKE students in technical and engineering fields may benefit from more structured environments, potentially lowering stress and promoting healthier lifestyles [30].

Logistic regression results show that university affiliation was a significant predictor of PA changes during the pandemic. UPJŠ students were 4.33 times more likely to maintain or increase PA than TUKE students (p=0.005). This indicates that institutional differences, such as access to facilities, programs, or social support, may have influenced students’ ability to stay active. During the pandemic, UPJŠ implemented a structured online physical education program. They provided a variety of programs in the home, including aerobics, yoga, Pilates, SPS (Spinal Stabilization), strength and conditioning, with all classes being live online sessions led by instructors to ensure active participation and proper technique monitoring [31] . These online live classes were complemented by individual self-reporting classes via Strava or Geocaching. These sessions included interactive elements, such as real-time corrections and the ability to communicate directly with instructors, which helped students maintain PA despite the constraints imposed by COVID-19 restrictions [32] . TUKE’s approach to physical education during the pandemic differed from UPJŠ’s, with a more individualized and less interactive model. Students had to select from a list of activities such as walking, running, hiking, cycling, or inline skating and record their results using mobile apps such as Strava and SportsTracker. These recorded activities were then sent to instructors for verification, allowing for flexibility but little real-time engagement or instructor interaction [33]. While this method allowed students to maintain PA on their terms, it lacked the structured, guided sessions seen at UPJŠ, which included live online classes and instructor feedback during workouts. TUKE students reported that while 67.4% found the method motivating enough to start using sports apps, nearly 52% preferred in-person physical education [33]. This preference highlights the limitations of TUKE’s system in fostering long-term engagement, compared to UPJŠ’s more comprehensive and interactive model that provides flexibility and real-time support. As a result, differences in PA maintenance between the two institutions may reflect not only the activities offered but also the varying levels of institutional involvement and student support during the pandemic. This emphasizes the importance of direct engagement and institutional support in promoting PA, especially in remote learning environments where student motivation can be difficult to maintain in the absence of interactive elements.

Gender was found to be a marginally significant predictor of PA changes, with female students being more likely to maintain or increase PA than males (p=0.078). While the gender results were marginal, they suggest that female students were more resilient in maintaining PA during the pandemic, possibly due to stronger coping strategies or adherence to structured routines [34]. However, more research into the specific strategies used by women to stay active is needed, especially given the conflicting evidence about the impact of stress on women’s PA levels.

Surprisingly, none of the PAR-Q’s health-related variables (such as heart problems, dizziness, and asthma) were significant predictors of changes in PA during the pandemic. This finding implies that, despite the presence of these health conditions, they had no significant effect on students’ ability to maintain or increase their PA levels. The lack of a significant predictive value for health-related variables from the PAR-Q (e.g. heart problems, dizziness, asthma) in predicting PA changes during the pandemic is consistent with findings from other studies. While such health conditions are generally associated with activity readiness, research suggests that they may not always predict changes in PA behavior during acute crises such as the pandemic. Instead, access to resources, psychological resilience, and motivation appear to be more important. Previous research discovered that during the pandemic, the psychological and motivational benefits of staying active outweighed physical limitations for many people, as structured exercise programs and mental health support were critical in maintaining activity levels [35]. Similarly, a different study emphasizes that long-term compliance with PA recommendations often depends more on psychological resilience and access to fitness opportunities rather than pre-existing health conditions [36].

Our findings emphasize the importance of institutional support for PA, especially in emergencies. Dizziness and asthma did not predict PA changes, but university support systems, gender differences in coping strategies, and structured programs did. These findings suggest that future interventions should focus on psychological resilience and resource availability to help students maintain healthy lifestyles during unprecedented disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

This study examines how the COVID-19 pandemic affected health factors influencing PA readiness among Eastern Slovakia university students from Košice. We expected to reveal detailed insights into how the pandemic affected certain demographic groups. Dizziness and chest pain were common self-reported health issues, but they did not predict pandemic PA levels. This suggests that institutional support, psychological resilience, and resource access may have been more important in determining PA readiness. Significant differences in PA maintenance between UPJŠ and TUKE students suggest institutional factors may be involved. UPJŠ students, with structured online fitness programs and institutional support, were more likely to maintain or increase PA than TUKE students, who used more individualized methods. These findings highlight the importance of institutional involvement in crisis health and well-being, especially when routines are disrupted. Female students reported more health issues but were more resilient in maintaining PA, possibly due to stronger coping mechanisms or structured routines. This study shows how health, institutional support, and psychological factors affect a worldwide crisis of PA patterns. Universities should consider how structured support systems can improve student health and resilience to such challenges.

This study has a few limitations that should be noted. First, the use of self-reported data from the PAR-Q may have introduced bias or inaccuracies, as participants may not have accurately remembered or reported their health conditions or PA levels. Furthermore, the use of cross-sectional data limits the ability to assess changes over time, making causal inference difficult. A longitudinal study design would provide more robust evidence of how health conditions and PA behaviors change over time. Another limitation is the small sample size for certain health conditions, such as diabetes, which necessitates the use of Fisher’s exact test. This may limit the generalizability of findings for these specific conditions, as the results may be less robust in a larger population.