Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is considered a T cell-mediated autoimmune disease with an unknown aetiology. Cytotoxic T cells play a central role in the pathogenesis of LP and these cells are known to significantly induce apoptosis in basal keratinocytes via a number of mechanisms: (i) affecting the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), granzyme B (GrB) and perforin, (ii) binding CD95L (FasL) on the T cell surface to CD95 (Fas) on the keratinocyte receptor, and (iii) triggering the activation of caspase-2, -3, -8, and -12 [1, 2].

Pentraxins are critical proteins of innate immunity and are divided into two groups, including short pentraxins (C-reactive protein [CRP] and serum amyloid P-component [SAP]) and long pentraxins (pentraxin 3 [PTX3]) [3, 4]. Short pentraxins are released only from the liver and in systemic inflammatory conditions, while PTX3 is tissue-specific and is released locally by macrophages, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, dendritic cells, and adipocytes. Serum levels of PTX3 can occasionally increase up to 500 times its normal level due to the rapid increase in PTX3 in the blood, aggravation in local inflammation, and tissue damage. Due to these features, PTX3 is potentially a more specific marker in various diseases [5, 6]. A study measuring levels of PTX3 found that PTX3 levels peak at 7.5 h after admission and return to normal range at 12 ±4 days in most patients [7]. Additionally, its effectiveness has been shown in cardiovascular diseases, lung cancer, chronic kidney disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus. The most critical effect of PTX is on the complement system. Of note, by affecting the complement system, PTX3 enables the recognition of apoptotic cells by phagocytes and also opsonizes these cells. On the other hand, increased PTX3 expression in tissue damage and in some cancers is explained by its effect on apoptosis [8–11].

Aim

The aim of this study was to correlate PTX3 with apoptosis in basal cell keratinocytes in LP and to determine whether it is a marker in this disease.

Material and methods

The study included patients who had recently been diagnosed with LP. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) providing written consent for participation, (ii) presence of typical clinical findings (livid-red, violaceous, flat-topped polygonal papules and plaques, fern appearance in the oral mucosa, flexural involvement, and Wickham’s striae), (iii) histopathological confirmation of LP (demonstration of apoptosis and vacuolar degeneration of keratinocytes with marked individual keratinocyte necrosis in the basal layer of the epidermis, band-like lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis, and irregular epidermal hyperplasia), (iv) age of 18–70 years and (v) > 10% of the body surface area (BSA) and severe mucosal involvement.

Exclusion criteria included the use of anti-inflammatory drugs that could affect serum PTX3 level within the last 2 weeks and a history of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases including renal and hepatic diseases, cardiac insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, malignancies, pregnancy, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and LP patients under treatment or in remission. The control group included 30 healthy individuals with no family history of autoimmune and bullous diseases and no history of medical treatment.

Blood sampling and analysis

Venous blood samples were obtained for routine biochemical analyses in the Dermatology Department. The samples were placed in yellow-top tubes with no anticoagulant and then transferred to the Biochemistry Department. Following the coagulation process, serum was separated after centrifuging at 1,500 g for 10 min. Human PTX3 concentration was measured with a commercially available ELISA kit, Eastbiopharm (Eastbiopharm, Zhejiang, China), using a double antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The PTX3 results were expressed as ng/ml.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 15.0 (Chicago, SPSS Inc.). Normal distribution of data was assessed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with histograms and plots. Continuous variables were expressed as mean, standard deviation (SD), and median. Variables with non-normal distribution were compared using Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test. Correlations among continuous variables were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to assess the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of PTX3 in the prediction of LP. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 60 participants consisting of 40 women and 20 men were included in the study. There were 30 patients with LP in the study. Of these, 21 (70%) patients had skin involvement only, 2 (6.7%) patients had mucosal involvement only, and 7 (23.3%) patients had both skin and mucosal involvement of LP. Moreover, 53.3% of the patients had severe itching and 20% of them had moderate itching (Table 1). No significant difference was found between groups in terms of age and gender (Table 2). There was a significant difference in PTX3 levels between groups (Table 3).

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of patients

| Parameter | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement | Skin | 21 | (70.0) |

| Mucosa | 2 | (6.7) | |

| Mucosa and skin | 7 | (23.3) | |

| Itching | None | 2 | (6.7) |

| Mild | 6 | (20.0) | |

| Moderate | 6 | (20.0) | |

| Severe | 16 | (53.3) | |

| Disease duration [months]* | 8.6 ±6.3 | 6.5 | |

Table 2

Comparison of mean age and gender distribution

| Parameter | Group | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LP | Control | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Gender | Female | 20 | (66.7) | 20 | (66.7) | > 0.9991 |

| Male | 10 | (33.3) | 10 | (33.3) | ||

| Age [years]* | 41.5 ±12.4 | 43.5 | 43.4 ±13.0 | 44.5 | 0.5642 | |

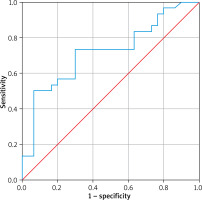

In the ROC analysis, the cut-off value for PTX3 level (ng/ml) in the prediction of LP was found to be 1.013. At this cut-off value, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.718 (range: 0.587–0.850) and was statistically significant (p = 0.004) (Table 4).

Table 4

ROC curve results for the prediction of LP by PTX3

| AUC | 95%CI | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| PTX3 | 0.718 | 0.587 | 0.850 | 0.004 |

In the ROC curve analysis, the cut-off value for PTX3 in the prediction of LP was found to be statistically significant. The results of the analysis are presented in Table 4 (p = 0.004) and Figure 1.

Discussion

Our study showed that the PTX3 level increases in LP. To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting on the relationship between PTX3 and LP.

It is known that PTX3 is absent in normal skin, while it accumulates in tissue and thus its serum levels increase in inflammatory conditions [12, 13]. Similarly, PTX3 serum levels were significantly higher in our LP patients compared to the control group.

The literature indicates that apoptosis in basal keratinocytes plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of LP and that PTX leads to phagocytic uptake of apoptotic cells in the presence of inflammation [9, 10]. In a previous study, Rovere et al. showed that PTX3 binds to apoptotic cells and thus has a critical role in apoptosis [14]. Likewise, Shiraki et al. suggested that PTX3 affects apoptosis in the early phase of inflammation [15]. On the other hand, a study conducted in PTX3-free rats showed that PTX reduced the clearance of apoptotic cells [11].

In our study, serum PTX3 levels were significantly higher in LP patients compared to control subjects. This finding implicates that PTX3 serum levels may be a useful parameter to be assessed in LP patients.

Numerous studies have shown that serum PTX3 levels increase in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and that this elevation may be associated with disease activation. The authors also noted that this phenomenon could be a result of apoptosis as well as the effect of systemic lupus erythematosus on the complement system [10]. Similarly, in our study, increased apoptosis in LP may contribute to elevated serum PTX3 levels, although there are other factors to be considered such as stress and other systemic causes [12].

A study by Sahar et al. showed that serum PTX3 is a potential indicator of cutaneous disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus [10, 16]. This finding was supported by the findings of our study.

Numerous studies have suggested that CRP, which is a short pentraxin, increases in LP and may indicate disease activation. It has also been reported that short pentraxins such as CRP and serum amyloid P component (SAP) are highly effective in binding to dead cells rather than apoptotic cells and are better markers of local inflammation, while PTX3, which is a long pentraxin, is a better marker of apoptotic events and systemic inflammation. Additionally, some other studies indicated that since LP shows extensive involvement (skin, mucosa, nail, hair), PTX3 may be a useful tool in the diagnosis of LP [17].

Several studies have also reported that PTX3 has a key role in diseases with a significant dermatological component such as leprosy, psoriasis, urticaria, Behçet’s disease and that it could be a novel marker for these diseases. Moreover, these studies also suggested that PTX3 could be responsible for the expression of inflammatory mediators [18–21]. Based on the findings of our study, we consider that PTX3 may be associated with apoptosis rather than the inflammatory mediators that are commonly used in the diagnosis of other dermatological diseases.

Our study had several limitations. First, it is a single-centre study and had a small number of patients. Second, PTX3 levels were not assessed at month 6 after treatment. Another limitation of our study is that, while other studies in the literature have focused mostly on systemic diseases, ours is conducted on a skin-limited disease. Also while our study focuses on measuring serum levels of PTX3, several factors may influence these levels. Therefore, a study measuring PTX3 levels directly in LP lesions is needed to further determine the role of PTX3 in LP patients.

There are several confounding factors in our study, such as stress, which can exacerbate LP and also increase serum levels of PTX3.