Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic pruritic inflammatory skin disease characterized by barrier dysfunction and immune dysregulation, which can occur at any age. It is estimated that approximately 20% of children and 10% of adults worldwide suffer from AD [1–3]. Typical clinical symptoms of AD include severe itching and recurrent eczematous lesions, which can significantly affect patients’ sleep and quality of life [4]. The clinical treatment goals for AD are to alleviate skin itching, burning sensations, and changes in skin lesions, prevent disease exacerbation, and minimize treatment risks. Currently, the conventional systemic treatments for AD include corticosteroids and systemic immunomodulators; however, due to varying efficacy and safety concerns, their therapeutic effects may be limited. AD is a complex disease, and thus its treatment remains a challenge [5, 6].

JAK inhibitors (Janus kinase inhibitors) inhibit the JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signalling pathway by suppressing tyrosine kinases, playing a key role in coordinating immune responses. Several key cytokines utilize the JAK-STAT signalling pathway to transduce intracellular signals, which are involved in the pathogenesis of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, thereby achieving an anti-inflammatory effect [7, 8]. JAK inhibitors are effective potential drugs for treating AD as they may target several cytokine axes in the AD phenotype, making JAK inhibitors a promising treatment option for AD [8, 9]. Baricitinib is an oral selective JAK1/2 inhibitor that has been approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and alopecia areata [10–12]. Compared to traditional treatments, baricitinib can significantly improve treatment outcomes in patients with AD who have inadequate responses to conventional therapies. Several foreign randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [13–17] have studied the efficacy and safety of baricitinib in treating AD, and the results show that baricitinib has good efficacy and safety in treating AD.

This study aims to summarize relevant RCTs and use meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of baricitinib versus placebo for AD, with the goal of providing evidence-based guidance for clinical use.

Methods

Study type

The literature included in this study consists of publicly published RCTs, with the language limited to English.

Study subjects

Patients included in this study were all diagnosed with AD; age ≥ 18 years; no restrictions on race or nationality.

Interventions

Patients in the experimental group received baricitinib, while patients in the control group received a placebo; there were no restrictions on the dosage for both groups, with a treatment duration of 16 weeks.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures of this study include the proportion of patients with at least a 50% or 75% improvement from baseline in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score at week 16; secondary outcome indicators included: Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD), the proportion of patients with α ≥ 90% improvement from baseline in the EASI at week 16, SCORAD 75, and an improvement of ≥ 4 points in the Itch NRS score; safety indicators include: the incidence of adverse drug events, serious adverse events, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhoea, and others.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria for this study include: (1) reviews, systematic evaluations, case reports; (2) duplicate publications; (3) literature for which abstracts and detailed data cannot be obtained.

Literature search strategy

Computer searches of PubMed and Cochrane Library databases were performed. The English search terms included ‘baricitinib’, ‘atopic dermatitis’, and others. A combination of subject headings and free-text terms was used for the search, employing logical operators to formulate the search strategy and manually screening the included literature. The search timeframe was from the inception of each database until December 2024. Relevant randomized controlled trials were manually screened.

Literature screening and data extraction

Two researchers independently screened the literature according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion or with the assistance of a third party. The following data were extracted: the first author, publication year, number of patients, intervention measures, treatment duration, outcome indicators, etc.

Quality assessment of included literature

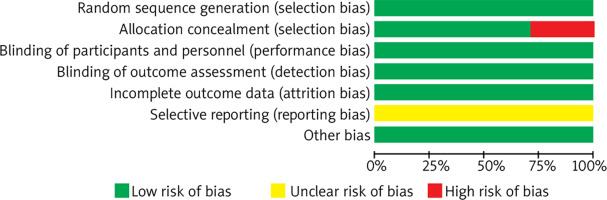

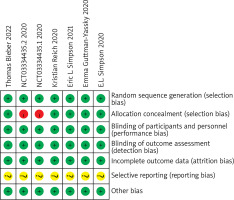

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the bias risk assessment tool recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0, which specifically includes: random allocation methods, whether allocation concealment was implemented, whether blinding was applied to study subjects, intervention implementers, and outcome assessors, whether outcome data were complete, whether selective reporting of outcomes occurred, and whether other biases were present. Each item was categorized as “low risk of bias”, “high risk of bias”, or “unclear”.

Statistical analysis

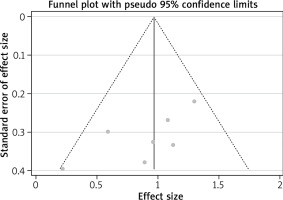

Meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.4 software. Binary variables are represented by odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). The heterogeneity among studies was assessed using χ2 test; if p < 0.1 and I2 > 50%, it indicates statistical heterogeneity among studies. After determining the source of heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used for analysis; otherwise, a fixed-effect model was employed. Sensitivity analysis was performed using the leave-one-out method; publication bias analysis was conducted using funnel plots and Egger’s test. The significance level was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Literature search results

A total of 6 relevant articles were obtained during the initial screening; after reviewing the titles, abstracts, and full texts, 6 articles and 7 RCTs were finally included. A total of 2966 patients were included, with cases in the experimental group and cases in the control group; the basic information of the included studies is shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Basic information of included studies

Quality assessment results of included studies

A total of 6 articles and 7 RCTs were included. All studies employed random methods, of which five studies reported allocation concealment methods. All studies provided detailed explanations of loss to follow-up and dropout situations or conducted intention-to-treat analyses. One study did not employ allocation concealment. All study data were complete, with no selective reporting of results, and it was unclear whether there were other sources of bias. Results are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Meta-analysis results

Primary endpoints

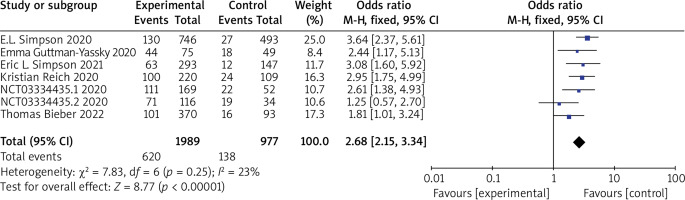

Seven RCTs reported EASI 50 or EASI 75, with no statistical heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.25, I 2 = 23%), and a fixed-effect model was used for the meta-analysis. The results showed that the patients in the experimental group had significantly higher EASI 50 or EASI 75 compared to the control group (OR = 2.68, 95% CI (2.15, 3.34), p < 0.00001). The results are shown in Figure 3.

Secondary endpoints

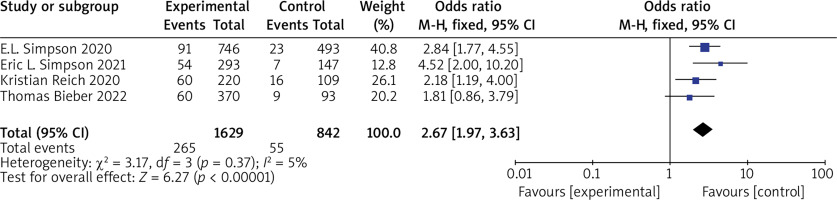

(1) vIGA-AD Five RCTs reported vIGA-AD, with no statistical heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.37, I 2 = 5%), and a fixed-effect model was used for the meta-analysis. The results show that vIGA-AD of patients in the experimental group was significantly higher than that of the control group (OR = 2.67, 95% CI (1.97, 3.63), p < 0.00001). The results are shown in Figure 4.

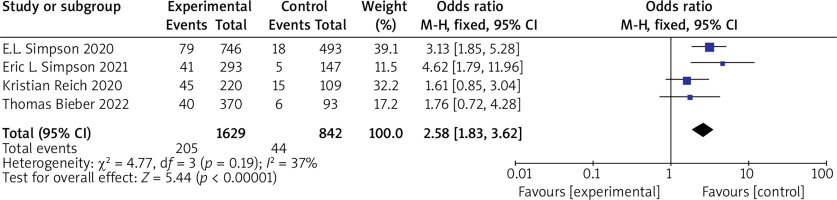

(2) EASI 90 Five RCTs reported EASI 90, with no statistical heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.19, I 2 = 37%), and a fixed-effect model was used for the meta-analysis. The results show that EASI 90 of patients in the experimental group was significantly higher than that of the control group (OR = 2.58, 95% CI (1.83, 3.62), p < 0.00001). The results are shown in Figure 5.

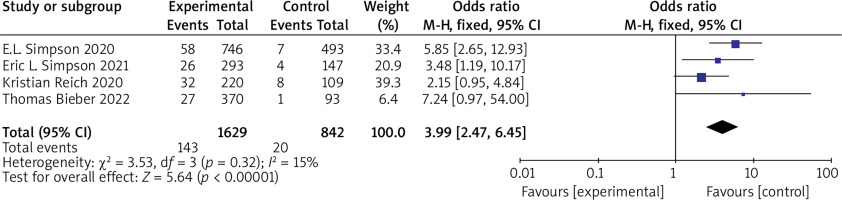

(3) SCORAD 75 Six RCTs reported SCORAD 75 with no statistical heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.32, I 2 = 15%), and a fixed-effect model was used for the meta-analysis. The results showed that SCORAD 75 in the experimental group was significantly higher than that in the control group (OR = 3.99, 95% CI (2.47, 6.45), p < 0.00001). The results are shown in Figure 6.

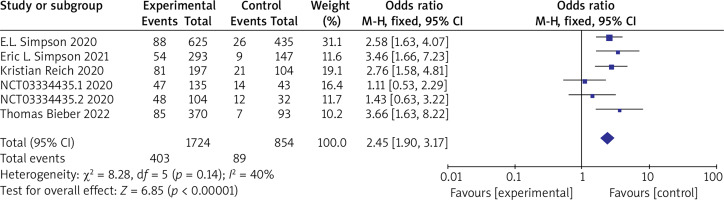

(4) NRS ≥ 4 Six RCTs reported NRS ≥ 4 with no statistical heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.14, I 2 = 40%), and a fixed-effect model was used for the meta-analysis. The results show that NRS ≥ 4 in the experimental group is significantly higher than that in the control group (OR = 2.45, 95% CI (1.90, 3.17), p < 0.00001). The results are shown in Figure 7.

Subgroup analysis of 1 mg and 2 mg

Five RCTs reported the trial results of baricitinib 1 mg and 2 mg, with no statistical heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.20, I 2 = 21%), and a fixed-effect model was used for the meta-analysis. The results show that the treatment effect in the 2 mg group is significantly higher than that in the 1 mg group (OR = 1.39, 95% CI (1.21, 1.60), p < 0.00001). The results are shown in Figure 8.

Subgroup analysis of 2 mg and 4 mg

Five RCTs reported the trial results of baricitinib 2 mg and 4 mg, with no statistical heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.99, I 2 = 0%), and a fixed-effect model was used for the meta-analysis. The results showed that the treatment effect in the 4 mg group was significantly higher than that in the 2 mg group (OR = 1.39, 95% CI (1.21, 1.61), p < 0.00001). The results are shown in Figure 9.

Safety indicators

The incidence rates of drug adverse reactions, serious adverse events, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, and diarrhoea were compared between the two groups, and the differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Meta-analysis of safety indicators in the two groups

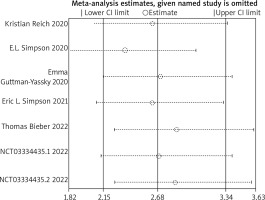

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted using the primary endpoint as an indicator. The results showed that the overall efficacy after sequentially excluding each study was not statistically significant compared to before exclusion. (p > 0.05), indicating that the results of this study are robust. The results are shown in Figure 10.

Publication bias analysis

Using the primary endpoint as an indicator, the p-value of Egger’s test was 0.066, and the scatter plots of each study were all within the inverted funnel range, with a basically symmetrical distribution, indicating that the possibility of publication bias in this study is relatively low. Results are shown in Table 3 and Figure 11.

Discussion

AD is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with the highest global disease burden, requiring active treatment and long-term management. Previous treatment options for AD included topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral antihistamines, systemic immunosuppressants, and corticosteroids [18]. In recent years, biologics and various small molecule drugs have been successively approved for the treatment of AD, providing more options for clinical practice while also presenting greater challenges for individualized patient management. JAK inhibitors are a class of small molecule drugs that can inhibit one or more JAK activities, thereby blocking the corresponding JAK-STAT signalling pathways. They are classified into non-selective and selective JAK inhibitors based on their target action [19]. The characteristics of JAK inhibitors include: oral small molecules, rapid onset of action, and response time of 1 to 2 weeks [20]. Therefore, the following situations may prioritize the selection of JAK inhibitors: (1) the need for rapid improvement of itching; (2) preference for oral administration and dosage flexibility; (3) the presence of diseases known to respond to JAK inhibitors, such as alopecia areata, vitiligo, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, etc. If adequate response is not achieved with low-dose JAK inhibitor monotherapy, consideration may be given to increasing the dose to promote rapid induction of remission. If there is no significant relief in skin lesions and itching after increasing to the maximum effective dose for 16 weeks, other systemic treatment options (such as biologics, immunosuppressants, etc.) may be considered [21]. Baricitinib is a non-selective inhibitor that primarily inhibits JAK1 and JAK2, with a Tmax of approximately 1 h after oral administration [22]. Baricitinib has been approved in the European Union and Japan for adults with moderate to severe AD requiring systemic treatment [23, 24], with a recommended dose of 4 mg once daily, orally, which may be reduced to 2 mg once daily based on the patient’s condition; however, it has not yet been approved for the treatment of AD in China, thus limiting clinical treatment options. The results of this study indicate that the efficacy of the experimental group patients is significantly higher than that of the control group. The subgroup analysis shows a significant difference in efficacy between the 1 mg and 2 mg doses, suggesting that the 2 mg dose is more effective than the 1 mg dose; therefore, the use of 1 mg baricitinib for treating AD is not recommended. In comparison between the 2 mg and 4 mg doses, there is a significant difference in overall efficacy; however, some efficacy assessment indicators show statistical differences while others do not. This indicates that when treating AD with baricitinib, a starting dose of 2 mg can be administered, and if the treatment response is insufficient, the dosage may be increased to 4 mg once daily. According to the condition, the dose can be reduced from 4 mg to 2 mg for maintenance, which can lower treatment costs while ensuring therapeutic efficacy, providing patients with a better treatment plan. In addition, the remission rate of patients in the experimental group was significantly higher than that of the control group, while the incidence rates of adverse drug events, serious adverse events, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, and diarrhoea were not statistically significant between the two groups. This indicates that baricitinib is more effective in alleviating symptoms compared to other traditional treatment medications, and it does not compromise treatment safety. In summary, baricitinib demonstrates good efficacy and safety in the treatment of AD. This study has the following limitations: (1) the sample size of the included studies is relatively small, which may lead to bias in the results; (2) some of the included studies have a short follow-up period, lacking large-sample long-term clinical studies on efficacy and safety; (3) this study may have certain statistical heterogeneity; (4) there are relatively few studies included in the subgroup analysis. Therefore, the conclusions drawn from this study require further validation through more large-sample, high-quality RCTs.