Introduction

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), originally termed “dysmorphophobia”, is a psychiatric condition in which body image concerns become excessive and quite devastating. People with the disorder display a constant preoccupation with an imagined physical defect (ICD-10) [1]. Therefore patients seeking help for aesthetic reasons should be screened for psychiatric conditions such as BDD so that they can be identified timely and referred for psychiatric consultation and management [1]. Common examples of these habits are constant mirror checking, comparing with others, extensive grooming (e.g., applying makeup and hairstyling), frequent clothes change, reassurance seeking, and eating a limited diet [2]. It has been seen that the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in general patients ranges from around 2% [3] of those seeking a dermatological cure from 8.5% to 15.0% [4], and among patients who seek cosmetic treatments from 2.9% to 53.6% [5, 6].

A study done in Saudi Arabia showed that in the population under study, the prevalence of BDD was 9.5% [1]. Nonetheless, it was discovered that the prevalence of BDD has no significant association with any factors [7]. A study was conducted on 497 patients from the dermatological outpatient clinic at the King Khalid University Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and 14.1% of them tested positive for BDD [8]. According to the study by Conrado et al., the cosmetic group had a greater current prevalence (14.0%) than the general (6.7%) and control (2.0%) groups. No prior diagnosis was made for any patient. The majority of BDD patients in the cosmetic group were not delighted with how dermatological treatments turned out [9]. According to another study conducted in the USA, 6.1% of people had BDD in comparison to the non-BDD group. The BDD group’s mean age was 25.88 ±7.140 years, which was lower than in the non-BDD group and the majority of BDD patients were female (62.5%). All of them were worried about facial deformities [10]. Research on female patients from Sweden revealed that among female Swedish dermatology patients, the prevalence of BDD was 4.9% (95% CI: 3.2–7.4). Patients with positive BDD screening reported anxiety (HADS A ≥ 11) four times more frequently (48% vs. 11%), and depression (HADS D ≥ 11) more frequently (almost ten times) than those with negative BDD screening [11]. Significant morbidity, such as suicidal thoughts and attempts, is commonly linked to BDD. They with BDD will probably contact multiple doctors, ask for thorough workups, and put dermatologists under a lot of pressure to recommend inappropriate and inefficient therapies [12].

Material and methods

All male and female patients of any age who present for dermatological and cosmetic indications in the Dermatology OPD of the Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital for 6 months were included in our study. Individual evaluation was done at the hospital Department of Dermatology and the Department of Psychiatry. The patients were divided into 2 groups and were compared according to study variables.

The first group was the general dermatology group. These were patients seeking consultation at the Dermatology OPD of the hospital for the most common general conditions in dermatology, e.g., acne, melasma, birthmarks, nevus, vitiligo and others that dermatologists frequently observe in general practice.

The next group was the cosmetic dermatology group. These were patients seeking consultation at the Dermatology OPD of the same hospital for cosmetic procedures involving conditions such as scars, aging, dyschromia, wrinkles, and skin lightening where they can receive both clinical treatments and minimally invasive procedures such as chemical peels, microdermabrasion, cutaneous augmentation, botulinum toxin injections, and non-ablative laser treatment for hair removal, photoaging, and skin tightening.

The ethical approval was obtained for the study from the Research Board of the hospital. Patients who were previously diagnosed with other forms of psychiatric conditions or recorded in OPD reports were excluded. Considering the prevalence of 11.9% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 8.0–15.8%) of patients screened positive for BDD as seen sample size of 161 was calculated.

The study uses the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire as one of its three primary measurements, together with sociodemographic data, and dermatological and previous psychological histories.

BDD questionnaire

A brief, self-reported questionnaire was employed to screen for BDD, based on the diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-IV [13]. To screen positive for BDD, respondents were required to meet the DSM-IV criteria, including a preoccupation with a perceived defect in physical appearance and the presence of at least moderate distress or functional impairment. In a dermatologic cosmetic surgery setting, this instrument has demonstrated a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 92.3% [14].

The questionnaire was translated into Nepali by Mr Prem Adhikari (M.A.), and subsequently back-translated into English by Mr Dambar Bahadur Thapa (M.A. in English Literature). The accuracy and cultural relevance of the translation were verified by Assistant Prof. Prateek Yonjan Lama from the Department of Psychiatry.

All completed proformas were meticulously reviewed to ensure data completeness. Data entry was conducted using Microsoft Excel (version 2021), followed by comprehensive data cleaning procedures. Subsequent data analysis was performed on the cleaned dataset.

Results

Among 161 patients of mean age 28.02 ±5.89 years seeking dermatological consultations, 25 patients, including 20 females and 5 males (15.5%), had met the criteria for BDD. Among patients with BDD, 15 (9.3%) patients had cosmetic problems while 10 (6.2%) patients had other dermatological problems.

Defect rating

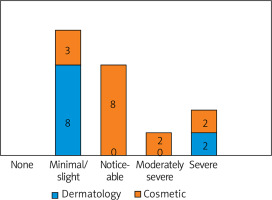

According to the defect rating scale that is applied for the clinician administered diagnostic module of the BDD Questionnaire, the majority of patients (n = 11, 44%) exhibited minimal to slight limitations. A statistically significant association was found between higher defect scores among cosmetic concern groups using the c2 test (p < 0.05) (Figure 1).

Distress, torrent, or pain

Most patients had mild (8, 32%) and moderate (7, 28%) severity in distress, torrent or pain (Table 1).

Table 1

Distress, torrent or pain severity

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| No distress | 3 | 12% |

| Mild, and not too disturbing | 8 | 32% |

| Moderate and disturbing but still manageable | 7 | 28% |

| Severe, and very disturbing | 3 | 12% |

| Extreme and disabling | 4 | 16% |

In terms of impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning, most participants reported some degree of limitation. Specifically, 8 (32%) individuals experienced mild interference without impairment of overall performance, while 7 (28%) reported moderate, but manageable, interference. Severe impairment was noted in 4 (16%) participants, and 3 (12%) reported extreme, incapacitating effects. Only 3 (12%) participants reported no limitations in functioning (Table 2).

Table 2

Impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning

The mean age of participants was comparable between the two groups, with the general dermatology group averaging 27.5 ±6.65 years and the cosmetic dermatology group 29.3 ±6.59 years (p = 0.504), indicating no statistically significant age difference (Table 3).

Table 3

Comparison of BDD patients seeking dermatological and cosmetic services

In terms of functional impact

A majority in both groups reported significant interference in social life due to their defect (9/10) in the general dermatology group and (12/15) in the cosmetic dermatology group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.626).

Regarding interference with school, work, or role functioning, again, the majority of participants from both groups (8/10 general dermatology and 13/15 cosmetic dermatology) answered “Yes.” However, this difference also did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.554).

When asked whether they avoid certain things because of their defect, fewer participants responded affirmatively (3/10 general dermatology and 5/15 cosmetic dermatology), with no significant group difference observed (p = 1.000).

Discussion

In our study, 25 (15.5%) patients met the diagnostic criteria for BDD. Among these, 15 (9.3%) patients presented with cosmetic concerns, while 10 (6.2%) patients sought treatment for other dermatological issues. These findings are in line with previous studies reporting BDD prevalence ranging from approximately 2% in the general population [3], to 8.5–15.0% among dermatology patients, and 2.9–53.6% among those seeking cosmetic interventions [5, 6].

Comparable studies conducted in Saudi Arabia have reported BDD prevalence rates of 9.5% and 14.1% [7, 8], while studies from the United States and Sweden found prevalence rates of 6.1% and 4.9%, respectively [10, 11]. In the United States, one study reported that 11.9% (95% CI: 8.0–15.8%) of dermatology patients screened positive for BDD. Subgroup analyses from university cosmetic surgery settings and community dermatology practices reported BDD prevalence rates of 10.0% (95% CI: 6.1–13.9%) and 14.4% (95% CI: 8.5–20.3%), respectively [13].

In our cohort, most patients exhibited mild to moderate limitations on the defect rating scale, with associated distress, discomfort, and impairments in social, occupational, or other important domains of functioning. Prior research involving 250 individuals with BDD found that 75% had sought non-psychiatric medical treatments, of which 16% worsened BDD symptoms, and 72% yielded no benefit [12]. These findings emphasize the need to consider socioeconomic and ethnic factors, which may influence the presentation and outcomes of BDD across populations.

Significant associations were found in our study between age < 50 years (p = 0.039) and higher BDD scores, as well as between anxiety/depression (p < 0.001) and elevated BDD symptomatology. Moreover, an education level below high school was significantly associated with higher anxiety/depression scores (p = 0.031). A binary logistic regression analysis revealed that anxiety/depression symptoms were strongly associated with BDD (OR = 10.0; 95% CI: 4.1–28.2; p < 0.001) [14, 15].

A related study conducted in Turkey with 318 participants (151 in the cosmetic dermatology group and 167 in the general dermatology group) diagnosed 20 individuals with BDD, with a higher (but not statistically significant) prevalence in the cosmetic dermatology group (8.6% vs. 4.2%; p = 0.082) [16]. The most frequently reported concerns were physique and weight (40.0%), followed by acne (25.0%).

Taken together, these findings underscore that BDD is prevalent, often underdiagnosed, and potentially debilitating. Routine screening for BDD is recommended, particularly in dermatology, cosmetic surgery, mental health, and other aesthetic-related practices. Clinical attention is especially warranted when patients exhibit hallmark behaviours, such as excessive camouflage, ritualistic checking, or social avoidance, suggestive of underlying dysmorphic concerns.

Conclusions

BDD is a psychiatric condition that is relatively common and can lead to significant psychological distress and functional impairment. A substantial number of individuals with BDD misinterpret their concerns as purely cosmetic in nature and therefore seek help from cosmetic professionals, including dermatologists, rather than consulting mental health practitioners – often due to feelings of shame or embarrassment. Given that dermatological and aesthetic treatments typically offer little to no relief and may even exacerbate symptoms, it is crucial for dermatologists to recognize the signs of BDD. Optimal management requires referral to a clinician experienced in the treatment of BDD – ideally, a mental health professional or a dermatologist with training in psychodermatology.