Introduction

Acne vulgaris is the most widespread dermatological condition among adolescents, impacting nearly 9% of people worldwide [1]. Its persistent nature, along with the risk of permanent scarring, can profoundly affect individuals [2] not only in terms of physical appearance but also by contributing to psychological distress, diminished self-esteem, social withdrawal, and considerable financial burden due to ongoing treatment needs [3].

Scarring is a common and lasting complication of acne, affecting nearly half of patients, with severe scarring occurring in about 30% and often leading to significant cosmetic and psychological distress [4, 5]. Acne scars generally develop in two forms: those caused by excessive tissue growth such as keloids or hypertrophic scars, and those resulting from tissue loss, known as atrophic scars. Among all acne scar types, atrophic variants dominate (up to 90%), with ice-pick scars comprising the majority (60–70%), followed by boxcar and rolling forms [6].

There are several viable options for treatment of acne scars however no standardized therapeutic consensus has been reached yet [7]. Among those, chemical peeling is a widely established and commonly used treatment for atrophic acne scars, offering measurable improvements in skin texture and pigmentation [8]. In parallel, microneedling has emerged over the last decade as an effective and minimally invasive technique that stimulates dermal remodelling and has shown comparable efficacy in improving acne scarring [9, 10]. Both modalities are considered safe, cost-effective, and accessible.

A growing body of research has explored the use of combination therapies – particularly microneedling followed by chemical peeling – based on the rationale that chemical agents may better penetrate through microchannels induced by needling, potentially enhancing clinical outcomes [11]. Despite growing clinical interest, there remains a lack of focused, high-quality evidence directly comparing combination therapy to its individual components. Previous meta-analyses have tended to evaluate microneedling as a standalone intervention or in combination with various other techniques (e.g., PRP, lasers), often aggregating heterogeneous modalities under broad categories [10, 12, 13].

To date, no systematic review or quantitative synthesis has been conducted to specifically examine whether combining microneedling with chemical peeling offers a statistically and clinically significant advantage over either treatment alone. Furthermore, important patient-centred outcomes such as satisfaction, pain, tolerability, and quality of life are often underreported or inconsistently measured across trials. Similarly, the risk of bias in existing studies varies and has not been systematically evaluated in this context.

Aim

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to comprehensively assess and compare the efficacy and safety of combination therapy (microneedling + chemical peeling) versus microneedling or chemical peeling monotherapy in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.

Methods

This study adhered to the 2020 Prisma Guidelines and Cochrane Handbook for systematic review and meta-analysis guidelines. The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 checklist and was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251082268).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were based on the PICO format. The study population (P) included patients with acne scars. Interventions (I) involved treatment with chemical peeling combined with microneedling, compared to chemical peeling alone or microneedling alone (C). Studies were required to report at least one of the predefined outcomes (O), including grade of improvement, patient-reported satisfaction and side effects. Both randomised and non-randomised clinical trials were eligible for inclusion, with no restrictions on follow-up duration. Exclusion criteria included: non-English publications, case reports, reviews and non-comparative studies.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across PubMed (Medline), Cochrane Library, and Embase from inception to 25th June 2025. Search terms included: “Chemical peeling”, “Microneedling”, and “Acne scars”, combined using Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”. A full research strategy is available in supplementary material (Supplementary Material 1).

Extracted variables

Study identifiers (first author, publication year, country of origin, and design) were recorded for every eligible trial, together with participant characteristics (sample size, mean age, sex distribution, and any sex-stratified analyses). Comprehensive intervention details were captured for both regimens, including peeling agent and concentration, microneedling device type and needle parameters, the number of treatment sessions, and the inter-session interval. All reported measures of clinical efficacy were transcribed verbatim to maximise comparability across studies (Goodman and Baron grades, ECCA, Weighted Scar Severity, VAS, percentage-improvement scales, DLQI, and clinician- or patient-satisfaction ratings). Continuous outcomes (e.g., mean change in ECCA, Weighted Scar Severity, VAS, or DLQI) were extracted for narrative comparison. Morphology-specific results (rolling, boxcar, ice-pick), reported effect modifiers (age, scar duration, number of sessions), objective tissue or imaging findings, and all safety data (type and frequency of adverse events, withdrawals, downtime or healing period) were likewise collated.

Data collection process

Two independent reviewers (J.W. and A.B.) conducted the selection process. After duplicate removal using Zotero (version 7), titles and abstracts were screened, followed by full-text screening. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, or by consultation with a third author (J.S.).

Risk of bias assessment

Two independent reviewers (J.W. and A.B.) assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias 2 tool (RoB 2) for randomised controlled trials. For non-randomised trials, Cochrane risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions tool (Robins-I) was used. Any disagreements were adjudicated by a third author (J.S.). Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots to identify potential asymmetry and outlier studies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in RevMan software v5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration). Dichotomous outcomes were analysed using odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the I² statistic and the Cochran Q test, with I² >50% and p < 0.10 considered indicative of substantial heterogeneity. All analyses were conducted with a conservative approach using a DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model, regardless of heterogeneity levels. The pooled outcome was clinical improvement evaluated by physicians, treated as dichotomous and defined a priori as either a rating of “Excellent”, “Very Good”, or “Good” on a studyspecific percentage-improvement scale or a ≥ 1-grade reduction on a Goodman and Baron scar-grading scale. If the study had more than two arms in terms of comparator used (chemical peeling or microneedling), control arms were studied separately and the intervention group was split in the analysis among the subgroups. For studies that used a split-face design, we analysed the treatments as separate study arms across participants (betweenarm comparison) rather than as paired, within-patient (side-to-side) outcomes, because side-specific data were not consistently reported. We performed leave-one-out sensitivity analyses (sequentially omitting one study at a time) to evaluate the robustness of the pooled estimates and to identify influential outliers.

Results

Search results across PubMed (Medline), Embase and Cochrane showed 208 records (Figure 1). After removal of duplicate results, 136 records remained. 102 records were further excluded after title and abstract screening, and 34 records assessed for eligibility. Finally 9 studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis (Table 1).

Table 1

Demographic characteristics

| Study | Country | Mean age (SD) | Women (%) | Type of scars analysed | Combination treatment therapy | Microneedling monotherapy | Chemical peeling monotherapy | Follow-ups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali 2019 [15] | Egypt | NA | NA | Atrophic acne scars | Dermapen + Jessner’s solution every 2 weeks | Dermapen 2.5 mm needle, till pinpoint bleeding every 2 weeks ≤ 8 sessions | Jessner peel: 14 % salicylic + 14 % resorcinol + 14 % lactic acid in ethanol, 4–7 layers. Peel left for 5–10 min until uniform erythema or frosting, then rinsed every 2 weeks | Baseline + assessments at 1, 2, and 3 months after the last session |

| El-Domyati 2018 [14] | Egypt | 27.3 (4.1) | 75% | Atrophic acne scars (mostly Fitzpatrick III–IV) | Dermaroller ADROLL-TD + 15% TCA peeling immediately after needling 6 sessions every 2 weeks | Dermaroller (600 steel needles, 1.5 mm length), 6 sessions every 2 weeks, 8 passes in 4 directions | – | Baseline, 1 month, and 3 months after the first of two sessions (3-month visit = final) |

| Leheta 2014 [19] | Egypt | 30.7 (5.6) | NA | Rolling, boxcar, ice-pick scars | Dermaroller MF8 + TCA 20% 4 sessions 6 weeks apart | – | Phenol 60% 1 session with a few drops of croton-oil per litre | Single end-point at 8 months from baseline (both groups assessed at month 8) |

| Memon 2022 [18] | Pakistan | 28.1 (7.3) | 59% | Atrophic acne scars | Dermapen 1.5 mm, four passes per direction, 35% GA | Dermapen, 6 sessions every 2 weeks | 35% glycolic-acid peel | Final assessment immediately after the 6th session (week 12) – no further follow-up |

| Pakla-Misiur 2021 [16] | Poland | 30.1 (3.6) | 78% | Atrophic acne scars (Goodman-Baron II-IV) | Dermapen 1.0–1.5 mm, four passes; PRX – T33 (33% TCA + H2O2 + kojic) | Dermapen | PRX-T33 applied in two coats, massaged until absorbed | Baseline and 30 days after the 4th session (~90 days from baseline) |

| Rana 2017 [20] | India | 22.8 (3.6) | NA | Rolling, boxcar, ice-pick and mixed scars | Dermaroller 1.5 mm, four passes; 70% Glycolic acid, neutralised after 1 min | Dermaroller 1.5 mm 3 sessions at week 0, 6, 12 | – | Baseline + interim visits; final follow-up at week 22 (~5.5 months from baseline) |

| Saadawi 2018 [17] | Egypt | 29.2 (7.1) | 67% | Boxcar, icepick and rolling scars | Dermapen, depth not specified, 35% GA peeling | Dermapen 6 sessions, every 2 weeks | 35% glycolic acid peel | Baseline; assessments at 2 and 4 weeks after the 6th session – final at ~14 weeks from baseline |

| Shahbano 2023 [21] | Pakistan | 32.9 (7.0) | 85% | Ice-pick, boxcar, rolling scars | Dermapen 1.5 mm, six passes; 35% GA | – | 35% glycolic acid peel | Baseline and 1 month after the 6th session (~14 weeks from baseline) |

| Sharad 2011 [22] | India | NA | NA | Boxcar and rolling scars | Dermaroller; 35% GA | Dermaroller 1.5 mm, four passes, 5 sessions every weeks | – | Baseline, after each treatment session; final follow-up 3 months after the last (5th) session – ~37 weeks from baseline |

Nine studies were assessed as eligible for systematic review (Ali, El-Domyati, Leheta, Memon, Pakla-Misiur, Rana, Saadawi, Shahbano, Sharad), whereas 6 studies (Ali, El-Domyati, Memon, Pakla-Misiur, Saadawi, Shahbano) were assessed as eligible for quantitative synthesis in meta-analysis.

Overall, 228 patients were in the combination treatment group, 186 patients in the microneedling monotherapy group, and 152 patients in the chemical peeling monotherapy group. One study was split-face one [14]. Four studies were 3-arm ones comparing combination treatment with either microneedling or chemical peeling monotherapy [15–18]. Every randomised controlled trial (RCT) compared a combination regimen – microneedling (MN) immediately followed by or alternated with a chemical peel – to at least one single-modality arm (MN alone or peel alone). Peels included Jessner’s solution, TCA 15–20%, phenol, glycolic acid 35–70%, and the H2O2-enhanced PRX-T33 formulation. Treatment courses varied from three to six sessions (interval 2–6 weeks) except for Leheta et al. one-off phenol peel [19].

Across trials, mean participant age ranged from the mid-20s to early 30s; the pooled female proportion was ~66%. Most cohorts comprised Fitzpatrick skin types III–V, and baseline scar severity spanned Goodman and Baron grades 2–4 or ECCA scores > 120.

Qualitative synthesis

Clinical improvement

Across eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and one non-randomised trial published between 2011 and 2023, every study documented a clinically meaningful reduction in acne-scar severity after microneedling combined with a chemical peel [14–22]. Eight of the nine trials showed that the combination outperformed at least one single-modality arm [14–18, 20–22]. Pooled responder data indicated that ≥ 75% improvement (“very significant/very good”) was achieved in 40–50% of combination recipients versus ≤ 13% with microneedling or peeling alone, while thresholds of ≥ 50% improvement were reached by 80–97% of patients on combination protocols compared with 19–43% and 5–31% on the respective monotherapies [15, 17, 18, 21]. The sole exception, Leheta et al. [19] reported similarly large gains for a single deep phenol peel and for four sessions of microneedling + 20% TCA, with no between-group difference; nevertheless, both arms exceeded 69% mean scar-score reduction. In the two studies reporting ECCA scores (Echelle d’Évaluation Clinique des Cicatrices d’Acné), combination therapy with microneedling plus a glycolic acid (GA) peel consistently produced larger mean reductions than microneedling alone. In the randomised trial by Rana et al. [20], baseline ECCA scores were 111.90 ±29.78 in the microneedling arm and 112.93 ±31.80 in the microneedling + 70% GA arm; by week 22 they declined to 82.32 ±29.60 and 73.28 ±29.30, corresponding to mean decreases of 29.58 versus 39.65 points, respectively (p < 0.001). In the prospective comparative study by Sharad [22], pre-treatment ECCA scores averaged 133.67 ±28.81 (microneedling) and 124.67 ±31.54 (microneedling + 35% GA); post-treatment means were 102.33 ±30.93 and 62.67 ±26.18, yielding mean improvements of 31.33 versus 62.00 points in favour of the combination (p = 0.001).

Morphology-specific analyses in five trials confirmed that rolling and boxcar scars respond best, whereas ice-pick scars show limited change [15, 17, 19–21]. One RCT found treatment effect correlated positively with the number of sessions and negatively with patient age and scar duration [15], while another demonstrated significant benefit in women but not in men [16]. Notably, the alternating microneedling + 35% glycolic-acid arm in a paper by Memon et al. [18] still outperformed both monotherapies despite harbouring the highest baseline proportion of severe scars, underscoring a robust combination effect.

Patient-reported outcomes/Satisfaction

Patient-centred outcomes were reported in five of the nine trials and each favoured the combined microneedling + peel approach. In Leheta et al., 90% of participants – irrespective of the treatment arm – judged their scars 50–75% better, confirming the large objective gains seen in that study [19]. Pakla-Misiur et al. recorded the only formal quality-of-life data: Dermatology Life-Quality Index scores fell by -5.8 points with MN + PRX-T33 versus –3.0 with MN alone and –2.0 with peel alone, and the combination was the sole regimen to achieve a clinically meaningful DLQI improvement in men; DLQI change correlated strongly with residual scar severity (R ≈ 0.58–0.80) [16]. Rana et al. observed comparable drops in scar-VAS across arms but the addition of 70% glycolic acid yielded significantly higher skin-texture VAS at weeks 12 and 18 (mean 7.0 versus 6.0; p ≤ 0.003) [20]. In Saadawi et al., “very good” satisfaction was reported by 40% of patients in the MN + GA group versus 20% with MN and 10% with GA alone (p = 0.04) [17]. Finally, Sharad documented marked patient-perceived improvements in texture, pore size and post-acne pigmentation exclusively with the sequential MN + GA protocol [22].

Safety and adverse events

Across all nine studies, microneedling with peel protocols were well-tolerated, with no permanent or serious complications reported. The commonest reactions were transient procedural pain and erythema, seen chiefly in MN-containing arms (50–60% of cases) and resolving within 48–72 h [15, 17, 20]. Superficial desquamation occurred in one fifth of patients treated with Jessner’s solution [15], while brief burning sensations were typical of glycolic-acid monotherapy [17, 18].

Pigmentary changes were infrequent and self-limited: two Fitzpatrick IV volunteers developed short-lived post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation after MN + 15% TCA [14], 2 cases followed MN + 35% GA [21], and three arose after MN alone in a work by Sharad [22] all resolving with topical bleaching. A single episode of pustular folliculitis was noted in the MN + 70% GA arm [20]. The only withdrawals occurred in the study by Pakla-Misiur et al., where two participants experienced transient facial discoloration after sun exposure during the MN + PRX-T33 course; the remaining 95% completed treatment uneventfully [16].

One study highlighted peel-specific downtime: deep phenol produced prolonged erythema (3–4 months), universal transient hyperpigmentation (≤ 6 months) and acneiform eruptions, contrasting with the much milder PCI + 20% TCA regimen in the same trial [19]. Otherwise, adverse events were confined to short-lived oedema, bruising or discomfort, and no relapses or late sequelae were detected during follow-up periods of up to 3 months [15] or, in the phenol study, 8 months [19].

Other outcomes

Beyond the core clinical, satisfaction and safety endpoints, several trials reported additional, less-frequently captured measures that further illuminate the value of combining chemical peeling with microneedling. The study by Pakla-Misiur et al. showed that the microneedling + PRX-T33 arm produced the largest fall in Dermatology Life-Quality Index scores (–5.8 points overall) and was the only regimen to yield a clinically meaningful HRQoL gain in men; DLQI improvement tracked closely with the residual Goodman and Baron grade. The same study also documented excellent inter-rater reliability for scar scoring (Cohen’s κ ≈ 0.9) and a high completion rate – 95% of participants finished the combination protocol, with only two withdrawals after transient post-sun discoloration [16]. The study by El-Domyati et al. provided objective tissue evidence of benefit: histometry revealed significant epidermal thickening (up to ~65 µm) and biopsy specimens demonstrated denser, more orderly collagen bundles after six sessions of microneedling + 15% TCA or microneedling + PRP, changes that exceeded those seen with microneedling alone [14]. The study by Ali et al. identified prognostic factors, reporting that greater improvement correlated positively with the number of treatment sessions and negatively with patient age and scar duration [15]. Patient-centred cosmetic effects were highlighted by the study by Rana et al., in which the addition of a high-strength glycolic-acid peel led to superior gains in texture-VAS scores at weeks 12 and 18 [20], and by Sharad and Ali et al., which noted concurrent fading of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in combination arms [15, 22].

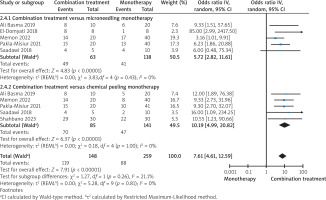

Quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis)

Compared to microneedling monotherapy, combination treatment resulted in a statistically significant improvement in acne scar outcomes (Figure 2; p = 0.006; OR = 5.72; 95% CI: 2.82–11.61; I² = 0%). Similarly, compared to chemical peeling alone, combination therapy also demonstrated significantly greater efficacy (Figure 2; p < 0.00001; OR = 8.94; 95% CI: 4.72–16.95; I² = 0%). In the pooled analysis, combination treatment yielded significantly greater clinical improvement than monotherapies (Figure 2; p < 0.00001, OR = 7.61; 95% CI: 4.61–12.59; I² = 0%). Sensitivity analysis showed that exclusion of any single study did not affect the results in either subgroup or the overall analysis.

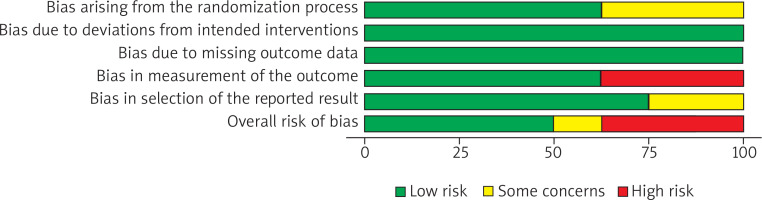

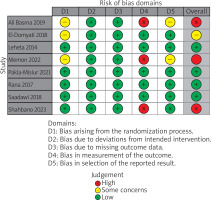

Risk of bias assessment

Out of 8 RCTs, 3 were evaluated as high risk of bias, 1 as some concerns and 5 as low risk of bias (Figures 3, 4). Across the three trials rated High risk of bias in Domain 4 (measurement of the outcome) a common pattern was heavy reliance on subjective clinical grading without adequately blinded, independent outcome assessment, a situation the RoB 2 guidance flags as high risk when knowledge of treatment could influence judgment [15, 18, 21]. In the study by Ali et al., percentage improvement categories were scored from post-treatment photographs on a quartile scale, but blinding of dermatologic assessors was not described, raising concern that expectations could shape ratings [15]. In the study conducted by Memon et al., outcomes were reported using an imprecisely specified “standard global scar grading system” with no description of who performed the assessments or whether they were blinded, and internally inconsistent result tables further undermined confidence in standardized measurement [18]. In the study conducted by Shahbano et al., change in Goodman grade (Excellent/Good/Poor) at followup was determined by the same consultant who delivered the interventions, with no blinding reported, creating clear potential for expectancy bias favouring the combination arm [21].

The study conducted by Sharad judged serious risk of bias as shown in Table 2, because participants were enrolled sequentially without randomisation or adjustment, creating serious potential confounding and selection bias [22]. All efficacy outcomes were assessed by the treating, unblinded dermatologist and several prespecified secondary outcomes were reported only narratively, raising serious measurement and selective-reporting concerns.

Table 2

Robins-I

| Study | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharad 2011 [21] | Serious | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

Publication bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed a symmetrical distribution of studies, suggesting a low risk of publication bias (Supplementary Figure S1). Given that fewer than ten studies were included in the meta-analysis, statistical tests for funnel plot asymmetry (such as Egger’s test) were not performed, in accordance with Cochrane recommendations.

Discussion

This review analyses findings from eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and one non-randomised trial, demonstrating that adding a chemical peel to microneedling offers several benefits in treating atrophic acne scars. Eight studies reported superiority over at least one monotherapy comparator, and pooled responder rates suggest that combination protocols approximately double the odds of achieving ≥ 50% and ≥ 75% clinical improvement.

This synergistic effect is supported by clinical and histological findings: microneedling stimulates neocollagenesis and epidermal renewal, while the addition of chemical peeling further enhances epidermal thickening and collagen remodelling [14]. In the study by El-Domyati et al. a combination of microneedling and 15% TCA peeling resulted in the greatest epidermal thickening (up to 67.4 µm) and more organised collagen structure compared to either treatment alone [14]. While certain scar types, especially rolling and boxcar scars, are known to respond better than ice-pick lesions [23], this analysis suggests that even these more treatment-resistant morphologies benefit significantly from combined therapy [15, 20, 21]. The observed advantage held across studies with varied treatment sequences [18] and peel types – from superficial Jessner’s solution to medium-depth TCA and deep phenol peels [19] – suggests that the synergy arises not from specific protocols but from the complementary biological effects of controlled epidermal disruption and dermal remodelling.

Patient-reported outcomes support the effectiveness of combination therapies, with studies showing greater improvements in DLQI scores and higher satisfaction compared to monotherapies [16, 17]. Notably, improvements in DLQI closely aligned with the extent of residual scarring, underscoring the clinical relevance of even modest reductions in scar severity.

Side effects like post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) were usually mild and temporary with moderate peels, but deeper peels such as phenol caused longer-lasting redness and PIH. This highlights the need to tailor acne scar treatments and peel choice carefully, especially for patients with darker skin tones [19]. Overall, the safety of combination therapy was reassuring. The most common side effects: redness, pain, and skin peeling, were mild and temporary, with no cases of lasting scarring, pigment changes, or serious complications. Only one study [16] reported two patients who stopped treatment due to temporary skin discoloration, pointing to the importance of good sun protection. However, many studies did not clearly report side effects, only one study evaluated how treatment affected patients’ quality of life with a validated tool.

Microneedling can be combined with various treatments such as platelet-rich plasma, hyaluronic acid, botulinum toxin A, chemical peels, and laser therapy to enhance acne scar outcomes but among these, the combination of microneedling with chemical peels showed the highest efficacy [24]. The exact mechanisms behind acne scar formation are not fully understood, but research suggests that scars are formed due to an atypical healing response triggered by epidermal inflammation, resulting in an imbalance between matrix breakdown and collagen biosynthesis [6, 25].

Male sex, a positive family history of acne, greater acne severity, delayed treatment initiation, and recurrent or prolonged inflammation have been identified as key risk factors contributing to the development of acne scars [6].

Acne scars significantly affect patients’ quality of life by causing embarrassment, low self-esteem, and social withdrawal [26]. Even mild scarring can lead to emotional distress, with the impact worsening as scar severity increases [5]. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating psychological assessment and support into the clinical management of acne scarring.

Laser and light-based therapies remain among the most effective options for treating acne scars, particularly atrophic ones [27–31]. Fractional CO2 laser resurfacing has demonstrated consistent clinical benefits [31]. However, their high cost, limited accessibility, and potential adverse effects, such as inflammation, infection, or post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, may limit broader use, especially in resource-limited settings [32, 33]. Although a range of other techniques, including microneedling, chemical peels, subcision, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and radiofrequency microneedling (RFM), have shown promising results and are often used in combination [30, 34, 35], therapeutic strategies remain heterogeneous. There is no standardized treatment protocol, and outcome assessment varies widely, often relying on subjective or non-validated scales [30]. These limitations highlight the importance of individualized, multimodal approaches and the need for more consistent, objective methods to evaluate treatment efficacy.

Microneedling has emerged as a widely used, minimally invasive technique in dermatology for skin rejuvenation and scar remodelling. Microneedles are tiny, minimally invasive needles that are made to create microchannels over a subcutaneous layer of the skin [36]. Studies demonstrate that repeated microneedling sessions lead to improvement in atrophic post-acne scars. This is associated with increased levels of collagen types I, III, and VII, as well as newly synthesized collagen, while total elastin levels tend to decrease following treatment [14]. Also it increases levels of key signalling molecules involved in collagen synthesis and neovascularization, such as glycosaminoglycans, VEGF, FGF-7, EGF, and TGF-β [37]. It is particularly favoured for patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V, as it carries a low risk of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation compared to laser treatments [7].

Another commonly employed strategy for treating acne scars is the use of chemical peels. These play a therapeutic role in acne scarring by inducing a controlled chemical injury that initiates exfoliation and stimulates skin regeneration [8]. This induces dermal remodelling by activating fibroblasts, enhancing collagen formation, and restructuring the extracellular matrix, all of which contribute to the softening and elevation of atrophic scars [38]. The extent of dermal remodelling depends on the depth of penetration, which varies with the type and concentration of the peeling agent.

In the treatment of acne scarring, the choice of chemical peel depends on the depth and type of lesions. Superficial scars are often addressed using glycolic acid (20–70%), lactic acid (92%), salicylic acid (30%), Jessner’s solution, or low concentrations of trichloroacetic acid (10–25%), which promote epidermal turnover and improve skin texture [39, 40]. For more pronounced lesions, medium-depth peels such as pyruvic acid (40–60%) and trichloroacetic acid (25–50%) are commonly used [8, 41]. Combining agents – like Jessner’s solution or salicylic acid with trichloroacetic acid – can enhance penetration and clinical efficacy. In cases of deep atrophic scarring, high-concentration trichloroacetic acid and phenol peels have demonstrated effectiveness, though they carry a higher risk of adverse effects and require careful patient selection [42]. The treatment of acne scars remains a controversial topic, with an increasing demand from patients for a less invasive approach with consistent efficacy and fewer side effects [33]. Both microneedling and chemical peels align with these expectations, as they are minimally invasive, cost-effective, and have demonstrated clinical benefit in improving atrophic acne scars.

The key strength of this body of evidence is the uniform direction of effect across heterogeneous settings, peel formulations and session schedules, lending confidence to the external validity of the findings. Split-face designs in two trials minimise inter-subject variability, and histological corroboration strengthens biological plausibility. However, several limitations temper the certainty of conclusions: (i) short follow-up (≤ 3 months in most studies) precludes assessment of durability and delayed PIH; (ii) risk of bias – few trials detailed allocation concealment or blinded outcome assessment; (iii) heterogeneous outcome measures hamper quantitative pooling; and (iv) under-representation of male patients and Fitzpatrick I–II skin types limits generalizability, and outcome assessment was further limited by minimal use of validated or objective tools.

For clinicians, the evidence supports microneedling plus a superficial-to-medium peel as first-line therapy for rolling and boxcar scars, reserving deeper phenol peels for selected patients willing to accept longer downtime. Given the sex-specific signal observed in one trial [16], future studies should stratify outcomes by gender and hormonal status. Research priorities include head-to-head comparisons with fractional laser resurfacing, optimisation of session number and interval, and the incorporation of longer follow-up with core outcome sets – encompassing scar morphology, texture, patient-reported impact and standardized adverse-event reporting – to allow meta-analysis. Exploration of adjuvants such as topical retinoids, growth factors or energy-based modalities delivered through microneedling channels may further enhance outcomes.

Conclusions

The aggregate RCT evidence positions the combination of microneedling and chemical peeling as the most consistently effective, safe and patient-valued intervention for atrophic acne scarring currently supported by randomised data. While methodological improvements are needed, the existing literature justifies adoption of dual protocols in routine practice and paves the way for nuanced optimisation guided by future high-quality trials.