A 14-year-old boy, a refugee from Ukraine, was examined at an outpatient clinic for a relapse of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). He had a history of CSU for 2 years, with three severe relapses requiring hospital treatment, including administration of systemic corticosteroids. He was also treated with antihistamines – fexofenadine, levocetirizine, and antileukotrienes with moderate effect as well as oral steroids with good effect. Additionally, he was treated also with mebendazole due to suspicion of intestinal parasites. Despite a report of allergies to pollen, house dust mites, and dogs, he did not have positive skin prick tests for these allergens and did not exhibit typical clinical symptoms.

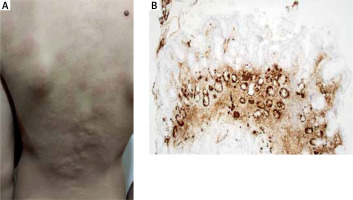

He displayed typical clinical symptoms of rapidly changing urticaria with severe itching (Figure 1). Blood samples were taken for biochemistry, complete blood count, autoimmune markers, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus serology, and parasitology. The results revealed a very low haemoglobin level of 95 g/l, iron deficiency with ferritin at 3.9 mg/l, and a moderate deficiency of vitamin B12 at 163 pmol/l. Allergy was ruled out by specific IgE to basic aero- and food allergens, extract-based and component-resolved diagnosis.

Figure 1

A – Urticaria with severe itching. B – Atrophic mucosa of the gastric body with focal intestinal metaplasia, and linear hyperplasia of ECL cells (chromogranin, 100×)

He showed moderate positivity for ANA (immunofluorescence method, titre 640) without positivity for other systemic autoantibodies. Antibodies for thyroid, liver, and coeliac disease were negative, but positivity for anti-parietal cell autoantibodies and elevated stool calprotectin (669 mg/kg) suggested a gastrointestinal autoimmune disease. Stool antigen test for Helicobacter pylori was negative. All other results were normal.

The abnormal test results (anemia, high calprotectin) and the progression of the rash despite the extensive antihistamine therapy necessitated admission to the paediatric department. Gastroduodenoscopy and coloscopy were performed, revealing diffuse erythema of the stomach body with numerous foci of atrophy and aphthae in the antrum, while other endoscopic findings were normal. Histological examination of biopsy samples confirmed a diagnosis of autoimmune atrophic gastritis (AAG), presenting atrophic chronic gastritis and hyperplasia of neuroendocrine enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells (Figure 1), indicating hypergastrinemia in achlorhydria. Our differential diagnostic assumption of elevated gastrin levels was serologically confirmed with a significantly high level of 93.7 ng/l (reference range: 1.7–7.6 ng/l).

Since a daily dose of 20 mg of levocetirizine [1, 2] was ineffective, we initiated treatment with bilastine 40 mg daily, which had a good clinical effect. The iron deficiency was addressed with oral ferrous sulfate and folic acid, normalizing the haemoglobin level in the blood count in 4 months of therapy. Vitamin B12 was supplemented parenterally. After discharge, the patient returned to Ukraine for follow-up.

CSU is characterized by the occurrence of wheals and/or angioedema daily or intermittently for more than 6 weeks without a specific trigger [1]. It can be associated with autoimmune diseases, such as thyroid disorders, celiac disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, and autoimmune gastritis [3, 4]. The prevalence of CSU in children is 0.5% [5].

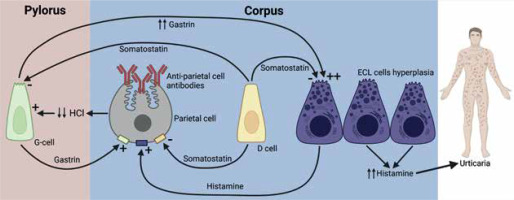

AAG is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease characterized by the destruction of oxyntic gastric mucosa, mucosal atrophy, metaplastic changes, and the presence of circulating autoantibodies against parietal cells and intrinsic factor [6]. The immune-mediated destruction of parietal cells leads to achlorhydria, stimulating excessive gastrin production by G cells in the duodenal antrum. Over time, this ineffective stimulation of ECL cells leads to hyperplasia and potentially their transformation into neuroendocrine tumours [7]. These findings suggest that CSU development could be caused by ECL hyperplasia and subsequent excessive histamine production (Figure 2), independent of Helicobacter pylori.

Figure 2

Pathophysiological connection between autoimmune gastritis and urticaria. Changes in acid secretion and enterochromaffin-like hyperplasia are part of the pathogenesis. This leads to an excess of histamine leaking into the circulation, which can cause chronic urticaria

AAG is exceedingly rare in children, with a prevalence of 0.15%, and more than half of children with AAG have another autoimmune disease [8], such as autoimmune thyroiditis (30–40%) [9]. In our patient’s case, we followed international guidelines for diagnosing CSU, including screening for possible autoimmunity [1]. If a paediatric patient presents with symptoms such as anemia, reduced vitamin B12 levels, recurrent CSU with no other plausible aetiology, positive anti-parietal cell antibodies, and elevated gastrin levels, AAG should be suspected, especially in patients with a history of CSU and/or autoimmune disorders.

We described a disorder with a very low incidence in the paediatric population. This condition should be considered in the differential diagnosis of CSU.