Introduction

A collision tumour (collision skin lesion – CSL) is a rather rare clinical and pathological diagnosis, which may cause a therapeutic difficulty, complicating or impairing physicians’ management with patients. It is defined as a lesion composed of at least two various cell populations – Independent benign and/or malignant neoplasms located in the immediate vicinity, but distinctly demarcated from each other [1, 2]. In 2020, Bulte et al. [1] presented a review in which researchers attempted to structure the classification and terminology of those tumours. They distinguished three possible collision tumour types, depending on malignancy of individual lesions. Within the first group, the tumour comprises of two benign lesions (e.g. melanocytic naevus and seborrheic keratosis). One benign and one malignant lesion constitute another type of collision tumour. This is the most common case and the most extensive group of all described ones. What is more, concomitance of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and melanocytic naevus is the most frequently diagnosed collision tumour in general. The last group is represented by tumours combined of two malignant lesions, and the most commonly reported example of this group is a BCC and melanoma composition [1–3].

Aim

In this study we aimed to analyse and present cases of collision skin lesions found among patients treated surgically in our Dermatosurgical Unit.

Material and methods

We performed a retrospective review of all patients treated in our Dermatosurgical Unit in the years 2021–2022. Lesions were composed of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) developing from actinic keratosis or BCC arising in port wine stains or within rhinophyma, scar or ulceration were excluded from the study, as well as cases in which two lesions were located in the same anatomical site but may clearly be separated during physical examination.

Results

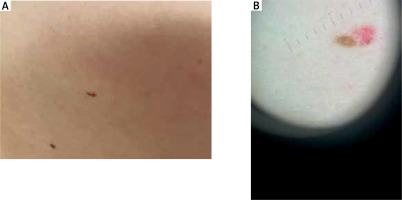

Among 838 treated patients we revealed 4 cases of collision tumours – 1 of ‘two benign lesions’ group and 3 of ‘one benign and one malignant lesion’ group. In all patients, diagnoses were confirmed histologically. The collision tumours were grouped with the patients’ demographic and clinical data in Table 1 and presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 1

Demographic and clinical details of patients with collision skin lesions (BCC – basal cell carcinoma)

Discussion

Pathogenesis of collision tumours is still intensively discussed. In cases of two malignancies such as BCC and melanoma it is considered an exposure to UV-radiation to be the major factor responsible for development of both neoplasms [4]. A role of an advancing patients’ age or skin type is described as well [5]. Additionally, some studies indicate that a presence of one tumour may provoke local epithelial or stromal alterations which increase a risk of another tumour’s development [3, 6]. There is also a hypothesis describing a relationship between two colluding tumours which origin from the similar cell type [7]. More studies need to be conducted to investigate this phenomenon.

Another entity that need to be differentiated from collision tumours is mixed tumours. Mixed tumours are characterized by the presence of different neoplastic components within the same tumour mass, which are believed to originate from a common progenitor cell that undergoes divergent differentiation [8]. Mixed Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) and SCC are characterized by intermingling of MCC and SCC components within a single tumour mass, with transitions between neuroendocrine and squamous differentiation [9]. These mixed tumours are predominantly Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) negative and exhibit a more aggressive behaviour compared to pure MCC. Conversely, a possible appearance of collision tumours consisting of two distinct neoplasms, MCC and SCC, that coexist in the same tissue area but remain separate at the histological level, indicate independent origins. Both mixed and collision tumours frequently occur in sun-damaged skin and are typically MCPyV-negative. Recent studies suggest that these tumours, despite their distinct appearances, may arise from a common keratinocytic precursor driven by UV radiation, sharing a high mutational burden and UV signature mutations. This points to a spectrum of UV-induced, MCPyV-negative MCC that includes both mixed and collision tumours, all exhibiting similar aggressive behaviour [9–11].

Not only the pathogenesis, but also the diagnostic process of such complex lesions may be challenging in everyday practice. They can easily be missed both clinically and histologically, especially when composed of one benign and one malignant lesion. Each patient described in our study caused diagnostic difficulties and was referred to our Unit with a diagnosis different than the one obtained after histopathological examination. None of the referring medical doctors suspected collision tumour.

Dermoscopy – as a non-invasive examination technique – is believed to improve clinician’s diagnostic and decision-making process. It allows to visualize live and directly pigmented and non-pigmented structures in the epidermis and superficial dermis (e.g. pigment network, vessels) [5, 12]. During CSL dermoscopy, it is considered to divide the examined lesion into 4 quadrants and inspect all of them for any presence of malignancy. Using both polarized and non-polarized light is also recommended [5].

Dermoscopy is commonly used to diagnose BCC. A pigmented reticular pattern is characteristic for melanocytic lesions such as naevi or solar lentigos. It is believed to be a negative diagnostic feature for pigmented BCC [13]. Nevertheless, it may rarely be observed in BCC lesions. Gulia et al. [14] published a study presenting 412 cases of BCC. Within 14 out of 412 (3.4%) lesions a typical pigment network was observed. In 9 tumours it was a result of collision with naevus, solar lentigo or actinic keratosis [14]. Such a collision (naevus and BCC) occurred also in one of analysed patients (Case 2).

In 2021 Fikrle et al. [15] collected and analysed 41 cases of collision skin tumours from a single department to assess correlations between a clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic picture of such lesions. In their study most frequently excised tumours comprised of one benign and one malignant lesion (25 out of 41 cases), which stays in line with results of other studies. In all investigated patients, researchers found corresponding dermoscopic structures and features that correlated with histopathological findings confirming the diagnoses. In some cases, second microscopic examination of samples was required due to inconsistent dermoscopic picture. In all these samples the description of the benign part of the colliding lesions was missing [15].

On the other hand, the dermoscopic picture can sometimes also be deceiving and lead to fixation errors, especially when the benign lesion prevails over the malignant tumour within a seemingly single structure or partially covers it [5]. Such an awareness may decrease the rate of underdiagnosed malignancies.

Moreover, the presence of collision tumour may lead to unnecessary biopsies, especially when the collision involves two benign lesions – because of its differed/different clinical and dermatoscopic morphology. If present, excisional biopsy seems to be a more favourable option [1, 6, 16].

Prognosis and success of the treatment in cases of collision tumours depends on the more malignant component (in one benign-one malignant and two malignant lesions) [6]. Interestingly, some studies indicate the role of a less aggressive neoplasm acting as a barrier protecting against more aggressive one’s invasion. Collision tumours are also reported to be less biologically aggressive [1, 7]. However, the role of an early, proper diagnosis and treatment is worth emphasizing. Further management should depend on guidelines for the more aggressive or malignant of all CSL compounds. Excision with the recommended margins brings satisfying results, especially when diagnosed early [6].