Introduction

The prevalence rate for chronic wounds in developed countries is up to 4% of the general population [1]. In Poland, according to statistical data, chronic wounds occur in over 760,000 people every year [2]. Statistics show that the number of patients with chronic wounds will tend to increase, due to the increasingly common occurrence of lifestyle-related diseases such as obesity, atherosclerosis, hypertension and diabetes, which are main risk factors for their development [3, 4].

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs), accounting for approximately 80% of all leg ulcers, are chronic wounds resulting from chronic venous insufficiency caused by venous valve dysfunction, deep vein obstruction, and gastrocnemius muscle insufficiency, causing venous insufficiency and associated venous hypertension. Other, less common causes of leg ulcers include: chronic arterial ischemia, vascular complications of diabetes, vasculitis, connective tissue diseases and bacterial infections. In total, leg ulcers of arterial and mixed aetiology, i.e. arteriovenous, account for approximately 20% of cases. In the course of venous insufficiency in the lower legs, trophic changes, discolorations, pimples and cracks appear on the skin covering varicose veins, and are accompanied by annoying itching. As a result of deepening changes, a necrotic zone develops, and the end result is the formation of an open wound – an ulcer. Ulceration in the skin most often occurs as a result of minor trauma to the area or for no apparent reason. VLUs cause severe and chronic pain in patients, increase the risk of infection, emit an unpleasant odour, seriously impede movement and reduce the quality of life of patients [4, 5].

The incidence of VLUs in the adult population ranges from 1% to 3%. Although the risk of VLUs increases with age, 22% of patients develop the first symptoms of VLUs before the age of 40, and 13% before the age of 30. The healing of VLUs is an extremely slow process, with a recurrence rate within 3 months of approximately 70% [4, 6].

According to the literature of the subject, compression therapy (CT) is the basic standard of care in the conservative treatment of VLUs. CT activity consists of creating external pressure on superficial veins and tissues, thereby promoting the return of venous blood to the vascular bed. Improving venous return helps reduce peripheral oedema and promotes the healing of lower limb wounds. Specialized dressings, selected according to the stage of wound healing and the intensity of the exudate produced, are also extremely useful in accelerating the healing of ulcers [7].

In accordance with the modern concept of treatment of difficult-to-heal wounds, including venous leg ulcers, the therapy of chronic wounds should be focused on interdisciplinary actions (with the involvement of a multidisciplinary team – MDT). This means the need to provide combined therapy taking into account various treatment methods, including physical medicine treatment procedures [8, 9].

Over the last three decades, there has been an increasing interest in the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) to treat difficult-to-heal wounds, including topical treatment applied directly to the ulcer [10, 11].

Aim

The aim of the study was to compare the results of treatment of patients with venous leg ulcers by means of comprehensive therapy including topical hyperbaric oxygen therapy based on planimetric assessment of the ulcer surface area and analysis of selected inflammatory markers and blood coagulation parameters.

Material and methods

In the retrospective study reported here, the treatment results of 57 patients with chronic venous leg ulcers hospitalized in the Department of Internal Medicine, Agiology and Physical Medicine of Medical University of Silesia in Bytom in the period 2018–2022 and treated with the use a comprehensive therapy including topical HBOT were analysed. The patients were in age range between 41 and 88 years (mean age: 56 ±8.75 years). The VLUs were diagnosed on the basis of consultation with a specialist in angiology, USG Doppler image and the value of ABI index > 0.9, performed in each patient, and used in order to eliminate patients with ulcer aetiopathogenesis other than venous one.

Patients were included in the study according to the following inclusion criteria: patients in age range of 18–90 years, of both sexes, with venous leg ulcers localized on the right or left lower limb in whom ulcers have not healed for at least 3 months or recurred, and who have not undergone vascular intervention for medical reasons, with no contraindications for the application of topical HBOT, who voluntary signed informed consent to participate in the study and complete the study procedures.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: patients’ age of < 18 and > 90 years, arterial and mixed ulcer type, previous surgical interventions, suffering from autoimmune diseases and malignant tumours, acute deep vein thrombosis, acute ischemia of the lower limbs, generalized infection requiring systemic antibiotic therapy, participating in another clinical trial, with incomplete clinical data, incapable of providing informed consent due to mental or behavioural disorders.

During hospitalization, all patients received identical conventional pharmacological treatment (sulodexide, micronized purified flavonoid fraction, pentoxifylline and acetylsalicylic acid in standard doses), procedures of cleansing wounds of necrotic tissue, daily wound inspection; specialized medical dressings (sterile hydrogel dressing Aqua-Gel (KIKGEL, Poland) and subsequent compression bandaging with the use of Codoban bandage (Tricomed, Łódź, Poland) (compression class 3) were applied for 17 h daily on patients’ affected legs in between the physical therapy procedures.

All analysed patients were divided into 2 groups with regard to the method of treatment.

In group 1 including 29 patients (16 females and 13 males), regardless of the routine local therapeutic procedure discussed above, the patients additionally underwent topical HBOT procedures using the Oxybaria-S device [12]. During the procedures, the patient’s lower limb, after being placed in a cylindrical therapeutic capsule closed with a flexible sealing cuff, was exposed to oxygen applied at the pressure of 1 mbar (2 kPa) and flow of approx. 6 l/min, the concentration of which inside the chamber was 90%, the procedures were performed once a day for 5 days a week, with a break for weekends (Saturday-Sunday). The procedures were performed in two series consisting of 15 treatment procedures each, and lasting 30 min each (for a total of 10 weeks including the intermission of 4 weeks between the two series of treatments).

In group 2 including 28 patients (16 females and 12 males) only the routine local therapeutic procedure was applied. Demographic characteristics of the patients were presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the study groups (number of patients: 57)

| Parameter | Total N = 57 (%) | Group 1 N = 29 (%) | Group 2 N = 28 (%) | *P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 28 (49.12) | 14 (48.28) | 14 (50) | 0.869 |

| Female | 29 (50.88) | 15 (51.72) | 14 (50) | |

| Age [years] | ||||

| < 60 | 26 (45.61) | 13 (44.83) | 13 (46.43) | 0.804 |

| ≥ 60 | 31 (54.39) | 16 (55.17) | 15 (53.57) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) [kg/m2] | ||||

| 18.5–24.99 | 26 (45.61) | 14 (48.28) | 12 (42.86) | 0.641 |

| 25.0–29.99 | 31 (54.39) | 15 (51.72) | 16 (57.14) | |

| Ulcer duration [years] | ||||

| < 2 | 24 (42.11) | 11 (37.93) | 13 (46.43) | 0.549 |

| ≥ 2 | 33 (57.89) | 18 (62.07) | 15 (53.57) | |

| Ulcer location | ||||

| Left leg | 25 (43.86) | 13 (44.83) | 12 (42.86) | 0.691 |

| Right leg | 32 (56.14) | 16 (55.17) | 16 (57.14) | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | ||||

| Yes | 31 (54.39) | 16 (55.17) | 15 (53.57) | 0.507 |

| No | 26 (45.61) | 13 (44.83) | 13 (46.43) | |

| Arterial hypertension | ||||

| Yes | 33 (57.89) | 17 (58.62) | 16 (57.14) | 0.052 |

| No | 24 (42.11) | 12 (41.38) | 12 (42.86) | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 14 (24.56) | 7 (24.14) | 7 (25) | 0.081 |

| No | 43 (75.44) | 22 (75.86) | 21 (75) | |

In all patients from both study groups, before the start of the therapeutic cycle and immediately after its completion, a panel of diagnostic tests was performed to assess the therapeutic effectiveness of standard treatment compared to treatment that additionally included topical HBO procedures, which tests included:

determination of selected coagulation parameters (serum concentration of fibrinogen and D-dimer),

determination of the concentration of selected inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein – CRP, white blood cell count – WBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate – ESR) in serum and blood,

planimetric assessment of the surface area of treated ulcers.

Procedure for performing laboratory tests

In case of all patients, in the mornings (between 7:00 a.m. and 9:00 a.m.), on an empty stomach, 10 ml samples of venous blood were collected from the antecubital vein in a sterile manner, using disposable equipment. Blood samples for determination of the concentration of CRP and D-dimer were collected into a clot tube, and then the determination was performed in the serum obtained after centrifugation of the blood. In turn, blood was collected into a test tube with an anticoagulant to determine the blood count parameters (WBC, ESR and fibrinogen concentration). All laboratory measurements were performed in the Central Laboratory of Specialist Hospital No. 2 in Bytom using the Cobas IT 3000 automatic diagnostic device.

Planimetric assessment of the ulcer surface area

Planimetric assessment of lesions via computer author’s program was performed in manually. In the first stage, a doctor loaded the analysed picture from a digital photo of a venous ulcer with a subsequent selection of lesion contours. The program allows for selection of areas of lesions in two modes. In the first mode, the analyst moves a mouse cursor continuously along the contour of the target area. After double-clicking the mouse cursor, the drawn contour is automatically closed, creating a closed curve. In the second mode, a selected contour is defined by indicating a set of points along a lesion contour. In this mode, the program automatically connects the new points with previously indicated points and as a result one gets a closed contour.

When the selection stage was done, the program automatically calculated the surface area within the previously defined contour. The surface area was represented in pixels or, after an adequate calculation, in square centimetres. In order to represent the surface area in square centimetres, it was necessary to calibrate the distance of the analysed body part from camera lens. To do this, during shooting, a given body part has been marked with a green square of 1 × 1 cm2. Thanks to this, the program could localize the aforementioned green square and calculate its size, and therefore, by performing scaling process assess the size of the ulcer [13].

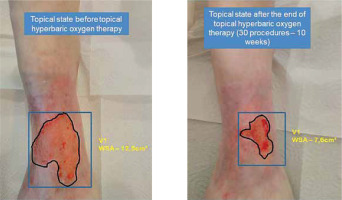

An example of the analysis of the change in the ulcer surface area before and after the completion of therapeutic procedures is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The topical state before and after 30 procedures of combined treatment including topical HBOT in a 78-female patient with venous leg ulcer (WSA – wound surface area)

All the therapeutic procedures with the use of HBOT were performed by an experienced physiotherapist, while the assessment of the ulcer surface area, also the determination of selected inflammatory markers and selected parameters of coagulation were conducted by an experienced doctor and professor of medicine performing scientific research.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the use of Statistica 13 package (StatSoft, Poland). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test the normality of data. There were non-normal distributions of data, except for that of the age of patients. The results of examined parameters were presented as median as well as lower and upper quartile (Q1–Q3), and the age was presented as mean and standard deviation. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two unmatched groups of non-parametric data. The Student t-test was used to compare the age between groups. Qualitative variables were assessed using the χ2 test. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The effect size was also calculated, with r = 0.1 indicating a small effect, r = 0.3 indicating a medium effect, and r = 0.5 indicating a large effect.

Results

The mean age of patients in group 1 was 68.9 ±8.9 years and did not differ statistically significantly (p = 0.989) from the mean age of patients in group 2, which was 69.0 ±11.1 years. The percentage of men and women did not show a statistically significant difference between both groups (p = 0.881).

Before the start of treatment, the mean value of the ulcer surface area did not differ statistically significantly between both groups. After the end of the therapeutic cycle, the average value of the ulcer surface area in group 1, which was 7.12 cm² (4.65–8.56), was statistically significantly (p = 0.019; effect size – 0.45) lower as compared to group 2, in which it was 8.98 cm² (6.48–10.18) (Table 2).

Table 2

Results regarding the analysis of the concentrations of selected inflammatory markers and parameters of blood coagulation in the studied groups of patients before and after therapy, with respect to the ulcer surface area along with statistical analysis

Before the start of treatment, the mean value of individual laboratory parameters did not differ statistically significantly between both groups. After the end of the therapeutic cycle, the average value of CRP concentration in group 1, which was 5.8 mg/l (2.27–12.0), was statistically significantly (p = 0.036; effect size – 0.27) lower compared to group 2, in which it was 8.53 mg/l (6.30–20.86). As regards the remaining analysed laboratory parameters, after the end of treatment, no statistically significant differences were noted between both groups of patients (Table 2).

No patient experienced any complications or side effects of the therapy during the therapeutic cycle, all patients tolerated the treatment well.

Discussion

With the dynamic development of science in recent decades, which has especially accelerated in the 21st century, hopes and expectations regarding the use of new therapies in treatment have been constantly increasing. New methods, including physical treatments, should ensure precision, repeatability, safety and, above all, effectiveness [14, 15].

The presented study assessed the effectiveness of comprehensive treatment of patients with VLUs, which included the use of a modern method of physical medicine – topical HBOT, including planimetric measurements of the ulcer surface area, and the determination of selected inflammatory markers and blood coagulation parameters. In the group of patients who, in addition to standard comprehensive treatment (pharmacotherapy, compression therapy, and specialized dressings), were also treated with topical HBOT, after the end of the therapeutic cycle we obtained statistically significantly lower mean values of the ulcer surface area, as compared to the group of patients who received standard treatment only. Moreover, in the group of patients treated with topical HBOT, statistically significantly lower values of CRP concentration, which is a sensitive inflammatory marker, were observed. However, no statistically significant differences were found in the remaining assessed inflammatory markers and parameters of blood coagulation.

Oxygen, as a key component of many metabolic processes, is necessary for proper wound healing. Chronic wounds are usually characterized by hypoxia because the partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) in the central part of the wound is often below the critical threshold necessary to fully support the enzymatic processes necessary for tissue “repair”. The delivery of additional oxygen, which is possible with topical HBOT, effectively increases pO2 levels, allowing for the optimization of the functioning of these essential enzymes. Although hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been well researched in this respect, comparative clinical trials continue to provide new evidence to support this therapeutic mechanism in the treatment of VLUs [16, 17].

One of the most advanced methods in difficult-to-heal wound treatment is HBOT. This method uses air at pressure, which is 1.5 to 3 times higher than, that consists of 100% oxygen on the whole human body in a special compartment called a hyperbaric chamber. During the therapy, patients sit inside the chamber with the higher-than-normal air pressure, simultaneously breathing pure oxygen through a mask. During HBOT, the patient is subjected to an oxygen pressure between 1.5 and 3 ATA (atmosphere absolute). HBOT is widely applied to chronic wounds in which high oxygen pressure accelerates neovascularization, reducing swelling and inflammation. That leads to improved tissue perfusion, reduced oedema and improved blood circulation. As a result, the above-mentioned mechanisms of this method support the healing processes. Moreover, the partial pressure of oxygen in tissues as well as the vesiculo-capillary gradient in the lungs increases and, most importantly in HBOT, the solubility of oxygen in blood plasma increases [18, 19].

Over the last few years, devices for the treatment of difficult-to-heal wounds, called topical hyperbaric oxygen therapy (THBOT), have appeared in the medical practice. These devices provide treatment for difficult-to-heal wounds at a pressure exceeding 1 ATA, applied in small chambers intended especially for single-limb therapies applied to open wounds. The processes occurring in topical hyperbaric oxygen therapy are similar to those in the whole-body treatment. It should be emphasized that so far the clinical data are not sufficient to estimate unequivocally the therapeutic efficacy of THBOT in contrast to HBOT. The mechanisms of THBOT’s actions are not yet fully known. Even though the oxygen pressure is much lower in THBOT than in HBOT, the main goal of the THBOT impact on tissues seem to be the improvement of healing processes and consequently, the decrease in the wound surface area and reduction of pain ailments. Studies have shown that topical pressurized oxygen therapy raises tissue O2 levels to a depth of 2 mm within the wound bed, stimulates new blood vessel formation, supports synthesis and maturation of collagen deposition, leading to increased tensile strength and decreased recurrence of the wound. Increased oxygen levels at the wound site have shown to lead to the timely closure of wounds. Increased wound oxygenation, through the application of topical pressurized oxygen, results in increased collagen deposition and tensile strength. Topically applied pressurized oxygen increases angiogenesis. That may be consistent with revascularisation and renewed healing. A lower recurrence rate may be expected in venous leg ulcers following topical pressurized oxygen therapy [20, 21].

THBOT is much cheaper, easier to use, easier available to patients, and based on the same physical phenomenon. Additionally, in many cases, these treatments can be used for patients who, due to medical reasons and identified contraindications, are disqualified from treatment in HBOT chambers. This method of delivery achieves tissue penetration and increased oxygen levels in the open wound without any risk of systemic oxygen toxicity [19, 21].

Bitterman and Muth indicated that adequate tissue oxygenation is crucial for activating and maintaining processes related to the repair of damaged tissue, healing, and preventing the growth of anaerobic bacteria within the wound. However, not all patients (especially those who cannot move on their own) are able, very often due to health and organizational limitations, to get to a centre providing systemic hyperbaric oxygen treatment (in hyperbaric chambers) every day. An alternative solution may be provided by the use of non-reimbursed portable devices for topical HBOT, which can be used at the patient’s home [22].

Pietrzak et al. assessed the therapeutic effectiveness of comprehensive therapy using topical HBOT in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. The material consisted of 36 patients (14 women and 22 men) aged from 18 to 80 years. Before the beginning and after the end of the therapeutic cycle (15 treatments), all patients had their ulcer surface area measured using the planimetric method and blood laboratory parameters were analysed. After completing the therapeutic cycle, a statistically significant reduction in the ulcer surface area was achieved. Moreover, laboratory tests showed a statistically significant decrease in the concentration of fibrinogen (a parameter of the coagulation system) and the concentration of the CRP inflammatory marker, as compared to the baseline values before the start of treatment [23].

In another study, Sinan et al. assessed the effect of HBOT on hemorheological and haematological parameters regarding red blood cell (RBC) deformability and aggregation, blood and plasma viscosity, and superoxide dismutase activity. After 20 HBOT sessions, a statistically significant decrease in the haematocrit level and red blood cell count was observed, as compared to the baseline values, yet there were no statistically significant changes in the values of hemorheological parameters [24].

Another study, published in 2023, assessed the impact of treatment with the application of HBOT upon oxidative stress, with the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by myeloperoxidase (MPO), and on the deformability of red blood cells in patients with acute or chronic inflammation (n = 10), in patients with acute carbon monoxide poisoning (n = 10), and in healthy volunteers (n = 10). The obtained results confirmed the occurrence of altered deformability of red blood cells in patients with acute and chronic diseases in reference to the basic inflammatory process after 10 treatments [25].

In a systematic review by De Wolde et al., the studies analysed concerned the impact of HBOT on oxidative stress, inflammation, and angiogenesis in humans. Analysis of the included studies showed that oxidative stress induced by HBOT reduces the concentration of pro-inflammatory acute phase proteins, interleukins and cytokines, and increases the amount of growth factors and other pro-angiogenetic cytokines, with several articles reporting these beneficial effects only after the first HBOT session or for a short time after each session [26].

In another review, Madero et al. analysed the pathophysiology of filler-induced vascular occlusion in an attempt to explain the multifaceted role of HBOT in rescuing ischemic tissue through the physical and biochemical mechanisms of HBOT, including its vasodilatory, antispasmodic and anti-inflammatory effects. The results confirmed that HBOT increases tissue oxygenation, modulates the formation of reactive oxygen species and affects angiogenesis, reducing hypoxia of the examined tissues [27].

Tölle et al. investigated the effect of hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) on the gene expression profile of gingival mesenchymal stem cells (G-MSC) isolated from five healthy individuals, activation of intracellular pathways, pluripotency, and differentiation potential in an experimental inflammatory model. Single (24 h) or double (72 h) stimulation with HBO (100% O2, 3 bar, 90 min) was performed under conditions of experimental inflammation. A beneficial, short-term effect improving their differentiation of single HBO stimulation on G-MSCs associated with anti-inflammatory and regenerative effects improving their differentiation has been demonstrated. The second stimulation did not produce such a positive effect [28].

In turn, Zhang et al. used an experimental wound ischemia model to test the hypothesis that HBOT accelerates wound healing by modulating hypoxia-inducible factor 1a (HIF-1a) signalling. In that study, rats with experimentally created skin wounds were divided into 3 groups. Animals from the first group were exposed to HBO every day (90 min, 2.4 atm), animals from the second group were systemically administered a free radical scavenger – N-acetylcysteine, while animals from the control group were neither exposed to HBO nor received N-acetylcysteine. The authors showed that HBOT improves the healing of ischemic wounds by reducing the level of HIF-1a and, consequently, the expression of the target gene with attenuation of cell apoptosis and reduced inflammation [29].

The authors of the study reported here are convinced that the use of comprehensive physical treatments using hyperbaric oxygen, demonstrating high therapeutic effectiveness and safety of therapy, is a promising treatment option for VLUs, which could effectively improve the quality of life of millions of patients and their families. Clear confirmation of the effectiveness and safety of topical HBO based on good-quality multicentre randomized clinical trials on large groups of patients will probably allow this method to be introduced into the standard treatment of VLUs in the future.

VLUs remain a significant clinical challenge. Numerous guidelines show that there is still no consensus among various specialists from various fields of medicine who deal with the treatment of difficult-to-heal wounds in their daily medical practice. Despite this, attempts are still made to analyse the quality and consistency of scientific publications. These results also show that in the entire treatment process it is important not only to fully engage interdisciplinary teams, which play a fundamental role, but also that more and more attention is paid to supportive treatment methods, which include physical medicine treatments and primary prevention, in which clinicians should actively participate. Patients with severe vascular disease, including complicated severe infections should be admitted to hospital for effective treatment. Mild to moderate cases can be treated on an outpatient basis. Physiotherapists should also be involved in the entire treatment program as they can offer patients many options for physical treatment, thus improving their quality of life. The results of the presented research confirm that one of such methods is topical HBOT used in the treatment of venous leg ulcers as a complementary therapy.

The study had some potential limitations, which include a limited number of participants and absence of a long-term follow-up. The sample size in the analysed group of patients was not calculated. The study also did not include the analysis of previous standards of care. It is possible that errors in measuring the contribution of risk factors occurred due to memory disorders of a given patient. Because information on ulcer duration is based on patient reports, this risk factor may also be subject to error. Therefore, the potential for generalizing the obtained results is limited.

The authors believe that supportive treatment using topical hyperbaric oxygen therapy application, after confirming the presented results in randomized trials on larger patient populations, will in the future constitute an element of comprehensive therapeutic treatment for patients with venous leg ulcers.

Conclusions

Comprehensive treatment of VLUs, additionally comprising topical HBOT, shows a greater therapeutic effectiveness compared to standard therapy, and the therapeutic effect of topical HBOT is associated with, among others, anti-inflammatory effect observed, without a significant impact on the parameters of coagulation. In order to clearly verify the mechanisms of the achieved therapeutic effect, it is advisable to conduct randomized clinical trials on a larger number of patients.