Introduction

Connective tissue diseases (CTDs), which include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Sjogren’s syndrome (SS), and so on, represent a group of autoimmune disorders that predominantly affect the body’s connective tissues. The pathogenesis of CTDs is complex and not entirely understood, but these diseases are known to potentially affect various organs and systems. A notable and frequent complication of CTDs is thrombocytopenia, which is defined by a platelet count below 100 × 109/l. Thrombocytopenia, particularly in its severe form (platelet count below 30 × 109/l), poses significant health burdens, including the potential for life-threatening gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding. Consequently, the severity of thrombocytopenia is recognized as an independent risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality in patients with SLE [1].

A challenging aspect in the management of CTDs is the occurrence of refractory thrombocytopenia (RTP), which is characterized by an inadequate response to standard treatments such as glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive therapy. In such cases, alternative therapeutic strategies, including thrombopoietin and its receptor agonists, rituximab, and splenectomy, are often considered. Dysregulation in the balance of immune cells, including different subsets of T cells (Th1, Th17 and Tregs) and B cells is considered to be a driving factor in the development of RTP [2, 3]. This situation may be caused by a deficiency or dysfunction of Treg cells, which allow autoreactive T cells to become uncontrollable and mediate the production of autoantibodies against platelets [4]. The anti-platelet autoantibodies produced by B cells play a central role in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), both in the Fc-dependent pathway-mediated increase in platelet destruction and in the non-Fc-dependent pathway-mediated inhibition of platelet production by megakaryocytes and the induction of desialylation that interferes with platelet production and impairs their lifespan [5]. Compared to non-refractory thrombocytopenia, RTP has a higher proportion of T cells involved in inflammation and immune activation [6]. Semple et al. have suggested that the elevated levels of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-10 in the serum of RTP patients are due to the accumulation of serum cytokines caused by abnormal activation of T cells [2]. The main function of Tregs is to block the pathogenic immune responses mediated by autoreactive cells, to establish and maintain immune homeostasis. It is reported that the population of Tregs is reduced in SS patients’ blood and salivary glands [7]. Studies have confirmed that the decreased Tregs levels are closely associated with SLE progression [8, 9]. The increase of Tregs results in the suppression of inflammatory response and the relief on pathological injury in SLE mice [10].

Recently, sirolimus, a macrolide antifungal antibiotic known for its immunosuppressive properties, has emerged as a promising treatment option for CTD-RTP [11, 12]. Sirolimus exerts its therapeutic effects primarily through the inhibition of the mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, which plays a crucial role in the activation of immune cells involved in inflammation [13].

Currently, there is limited research on the effect of sirolimus in the immune mechanism of CTD-RTP.

Aim

The main purpose of this study is to further verify the clinical efficacy and safety of sirolimus in patients with CTD-RTP and to explore the impact on various immunological parameters, including T cell subsets, regulatory T cells (Tregs), B cells and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood.

Material and methods

Study design

A retrospective, open-label, single-arm study was performed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of sirolimus in patients with CTD-RTP. The study was conducted following approval from the Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval No. [2022]091). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Subjects diagnosed with CTD-RTP were recruited from Xuanwu Hospital between November 2020 and December 2023.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

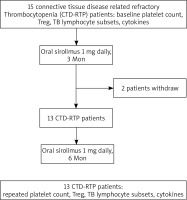

In this study, eligible participants were individuals 18 years of age or older who met the diagnostic criteria for connective tissue disease as outlined by either the American College of Rheumatology or the European League Against Rheumatism [14, 15]. All patients had thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 30 × 109/l at enrolment) and had previously not responded to at least one round of methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1 g/day for 3 consecutive days) and/or intravenous immunoglobulin G (20 g/day for 3–5 consecutive days) and/or had an inadequate response to glucocorticoids (prednisone 1 mg/kg/day or equivalent dose) or standard treatments, or had relapsed after glucocorticoid reduction. Patients in the study received treatments such as cyclophosphamide (1000 mg intravenous pulse monthly or 100 mg/day orally), mycophenolate mofetil (2–3 g/day), FK506 (tacrolimus; 2–3 mg/day), or MMF A (3–5 mg/kg/day). Oral prednisone was either continued or tapered to 5 mg in 8 weeks for maintenance. Previous immunosuppressants were maintained without introducing new ones during the study. Exclusion criteria comprised incomplete baseline data, secondary thrombocytopenia diseases, and severe infectious complications. The patient inclusion flow chart is detailed in Figure 1.

Efficacy evaluation

The efficacy of therapy was categorized as follows: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), and non-response (NR). CR was defined as a post-treatment platelet count of ≥ 100 × 109/l without bleeding. PR was indicated by a platelet count of ≥ 30 × 109/l, at least double the baseline count, without bleeding. NR was characterized by a post-treatment platelet count of < 30 × 109/l, less than double the baseline count or the presence of bleeding. Sustained effectiveness was defined as the maintenance of treatment efficacy for 6 months or longer. Early response was characterized by meeting the effectiveness criteria within 1 week of starting treatment. The initial response was identified when the effectiveness criteria were achieved 1 month after initiating treatment. Complete remission was indicated by a platelet count of ≥ 100 × 109/l, observed 12 months following the commencement of treatment. To determine CR or response (R), platelet counts were examined at least twice with a minimum interval of 7 days. Recurrence was determined based on at least two measurements with a minimum 1-day interval [16].

Laboratory measurements

(1) Cytokine detection: Cytokine levels were measured using flow cytometry. Peripheral blood samples were processed to obtain plasma, and the levels of cytokines (including interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12P70, IL-17A, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IFN-α) were quantified using a cytokine kit (Jiangxi Saiji Biotechnology) and the BD FACSAria II flow cytometer.

(2) T-cell and B-cell subset analysis: Immunophenotyping was performed on EDTA-anticoagulated peripheral blood samples. Monoclonal antibodies (including CD3-FITC, CD45-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD4-PE Cy7, CD56- PE, CD16-PE, CD19-APC, and CD8-APC-Cy) were used to characterize lymphocyte subpopulations. Percentages and absolute counts of each subset were determined using BD TrucountTM tubes (BD Biosciences).

Treg cell detection

Treg cells in peripheral blood were identified using 100 μl of EDTA anticoagulant blood, labelled with fluorescent antibodies including HLA-DR-FITC, CD4-PE-Cy7, CD45-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD25-PE, and CD127-PE-Cy7. The identification of CD3+CD4+CD25+CD127- cells as total Treg cells was performed, and their proportion in CD4+ T cells was quantified.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables following a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while non-normally distributed data were presented as median ± interquartile range (25th–75th percentile). The comparison of baseline characteristics was conducted using the independent samples t-test (for parameters with normal distribution) and Mann-Whitney test (for parameters that did not follow a normal distribution). The paired t-test was used to compare the two groups before and after treatment for numerical variables with a normal distribution, while the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for data not meeting the normal distribution assumption. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 26.0.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 13 patients (comprising 3 men and 10 women) diagnosed with CTD-RTP receiving sirolimus treatment were included in our study. Six patients met the diagnostic criteria for SLE, 7 patients met the criteria for primary Sjogren’s syndrome (pSS). The median age was 67 years old (ranging from 23 to 84 years). The median duration of CTD and thrombocytopenia was 3 years (range: 0.5 to 13 years) and 2 years (range: 0.5 to 7 years), respectively. All patients had platelet count below 30 × 109/l at the time of enrolment and had previously not responded to at least one round of methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1 g/day for 3 consecutive days) and/or intravenous immunoglobulin G (20 g/day for 3–5 consecutive days) and/or had an inadequate response to glucocorticoids (prednisone 1 mg/kg/day or equivalent dose) or standard treatments, or had relapsed after glucocorticoid reduction. Thus, they received the sirolimus therapy.

Clinical efficacy of sirolimus

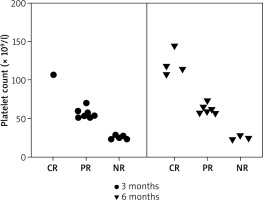

All 13 patients had baseline platelet counts below 30 × 109/l. Specifically, 2 (15.4%) patients had counts below 10 × 109/l, 4 (30.8%) patients had counts between 10 × 109/l and 20 × 109/l, and 7 (53.8%) patients had counts between 20 × 109/l and 30 × 109/l. After 3 months of sirolimus treatment (1 mg/day), 7 (53.8%) patients achieved PR, 5 (38.5%) patients showed NR, and 1 (7.69%) patient achieved CR, culminating in a total response rate of 61.5%. At the 6-month follow-up, 4 (30.8%) patients achieved CR, 6 (46.2%) patients maintained PR, and 3 (23.1%) patients continued to show NR. The overall effective rate (CR + PR) was 76.9% (Table 1, Figure 2). In 6 SLE patients, the CR rate, PR rate, and NR rate after 3 months of sirolimus treatment were 16.6%, 33.6%, and 50%, respectively. The CR rate, PR rate, and NR rate after 6 months of sirolimus treatment were 16.6%, 50%, and 33.3%, respectively. In 7 pSS patients, the CR rate, PR rate, and NR rate after 3 months of sirolimus treatment were 0%, 71.4%, and 28.6%, respectively. The CR rate, PR rate, and NR rate after 6 months of sirolimus treatment were 42.9%, 42.9%, and 14.3%, respectively.

Table 1

Clinical profile of 13 CTD-RTP patients treated with sirolimus

[i] t0 – age at diagnosis of connective tissue disease, t1 – duration of CTD. t2 – duration of thrombocytopenia. GCsmax – maximum dose of previous glucocorticoids, CTD – connective tissue disease, SLE – systemic lupus erythematosus, pSS – primary Sjogren’s syndrome, APS – antiphospholipid syndrome, CE – curative effect, CR – complete remission, PR – partial remission, NR – no response, Pred – prednisone, HCQ – hydroxychloroquine, MTX – methotrexate, MMF – mycophenolate mofetil, IVIG – intravenous immunoglobulin, CTX – cyclophosphamide, CsA – cyclosporine A, FK506 – tacrolimus, TII – tripterygium glycosides, MP – methylprednisolone, RTX – rituximab, HTN – hypertension, IPF – interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, AIHA – autoimmune haemolytic anemia, AF – atrial fibrillation, CHD – coronary heart disease, DVT – deep vein thrombosis, ADRs – adverse drug reactions

Safety

Regarding the safety of sirolimus treatment, no patients had experienced grade 2 or higher adverse events. Adverse reactions to sirolimus included oral ulcers (46.2%), hypercholesterolemia (38.5%), gastrointestinal reactions (7.7%), and fungal infections (7.7%). The adverse events observed after treatment with sirolimus are summarized in Table 1.

Immunological parameters

Flow cytometry analysis was performed to measure the lymphocyte subsets in patients before and after sirolimus treatment. We observed a notable alteration in the proportions of T subsets before and after sirolimus treatment. The results showed that, after sirolimus treatment, the ratio of Tregs (p < 0.05) was significantly increased. In contrast, after sirolimus treatment, the CD3+, CD8+, and CD4+ cell counts were significantly decreased (p < 0.05). However, the cell numbers of CD16+CD56+ NK cells and CD19+ B cells were not statistically significant before and after treatment (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2

Changes in platelet counts, Treg cell counts, and other lymphocyte subsets, before and after sirolimus treatment

| Parameter | Before treatment | After treatment | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treg cells (%) | 7.79 ±1.39 | 12.44 ±2.15 | 0.019* |

| Platelets (× 109/l) | 17.92 ±2.49 | 70.31 ±10.70 | < 0.001* |

| CD3+ T cells/μl | 1318.23 ±113.14 | 888.97 ±63.52 | 0.005** |

| CD8+ T cells/μl | 539.92 ±57.07 | 310.15 ±31.37 | 0.004** |

| CD4+ T cells/μl | 741.31 ±86.80 | 564.00 ±66.94 | 0.001** |

| CD16+CD56+ NK cells/μl | 213.01 ±34.05 | 184.69 ±26.86 | 0.270 |

| CD19+ B cells/μl | 279.00 (232.50, 340.00) | 234.00 (184.00, 269.50) | 0.687 |

Cytokine levels

The concentrations of cytokines in patients before and after treatment were detected. The results showed that, after sirolimus treatment, the levels of IL-8 and IL-17A were significantly reduced (p < 0.05). However, the levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-1B, IL-10, TNF-α, INF-α, IL-12 P70, and INF-γ were not statistically significant before and after treatment (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3

Cytokine levels before and after sirolimus treatment

| Cytokine | Before treatment [pg/ml] | After treatment [pg/ml] | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | 1.20 (0.15, 1.99) | 1.11 (0.84, 1.78) | 0.349 |

| IL-4 | 0.60 (0.04, 2.36) | 1.24 (0.35, 1.91) | 0.863 |

| IL-5 | 0.13 (0, 1.41) | 1.20 (0, 6.74) | 0.278 |

| IL-6 | 7.98 (2.39, 17.95) | 6.98 (3.75, 11.79) | 0.228 |

| IL-8 | 7.80 (6.80, 9.75) | 6.90 (6.00, 8.65) | 0.049* |

| IL-1B | 0.44 (0, 2.15) | 1.00 (0.61, 2.40) | 0.136 |

| IL-17A | 11.52 ±5.21 | 8.92 ±4.94 | 0.039* |

| IL-10 | 1.61 (0.93, 3.34) | 1.88 (1.43, 4.60) | 0.337 |

| TNF-α | 0.39 (0.93, 3.34) | 0.23 (0, 0.84) | 0.129 |

| INF-α | 0.38 (0, 0.95) | 0.30 (0, 0.89) | 0.943 |

| IL-12 P70 | 0 (0, 0.87) | 0.60 (0, 1.22) | 0.590 |

| INF-γ | 0.43 (0, 1.67) | 0.11 (0, 0.53) | 0.063 |

Discussion

CTD-RTP is characterized by an inadequate response to standard treatments such as glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive therapy. The current treatment methods include thrombopoietin and its receptor agonists, rituximab, and splenectomy. Our study concentrated on evaluating the efficacy of sirolimus in treating patients with CTD-RTP. We discovered that sirolimus treatment resulted in overall response rate of 61.5% at the 3 months after treatment and 76.9% at 6 months following treatment. These findings demonstrate that sirolimus may be effective for CTD-RTP treatment.

Sirolimus (an mTOR inhibitor), known for its low toxicity, has emerged as a potent treatment for refractory thrombocytopenia, particularly in patients with CTDs such as SLE [17] and primary Sjogren’s syndrome (pSS) [18]. A pilot study by Du et al. demonstrated that 50% of patients achieved CR and 16.7% achieved PR when sirolimus was administered in patients with CTD-RTP [12]. Our present clinical trial demonstrated that sirolimus was effective for CTD-RTP as evidenced by the significant increase of platelet count. After 3 months of sirolimus treatment, the total overall effective rate (CR + PR) was 61.5%. At the 6-month follow-up, 4 (30.8%) patients achieved CR, 6 (46.2%) patients maintained PR, and 3 (23.1%) patients continued to show NR. The overall effective rate was 76.9%, surpassing the rates reported in previous literature. The higher efficacy rate of sirolimus in our study, compared to previous reports, could be attributed to the inclusion of more patients with pSS. This study highlights sirolimus’s potential as an alternative regimen for refractory CTD-RTP, including in SLE and pSS patients. Importantly, the overall incidence of adverse reactions in our study was mild, primarily involving self-healing oral ulcers and mild hypercholesterolemia, which normalized following statin therapy. This safety profile is similar to findings from a study on high-dose sirolimus in kidney transplant rejection patients [19]. These results suggest that sirolimus, unlike other immunosuppressants such as rituximab or cyclosporine, which can have severe drug side effects leading to significant immune deficiency and infections, is suitable as a second-line option for treating immune-mediated thrombocytopenia. However, caution is advised when combining sirolimus with other immunosuppressants as there have been reports of fungal infections and alveolar haemorrhage in kidney transplant patients treated with sirolimus and mycophenolate mofetil [20]. In our study, 1 patient who received sirolimus and mycophenolate mofetil displayed a pulmonary fungal infection and subsequently experienced a temporary reduction in platelet count, which normalized after antifungal treatment. This underscores the importance of vigilance regarding potential fungal infections when using sirolimus in combination with other immunosuppressive agents. Altogether, sirolimus may be a safe and effective therapeutic option for CTD-RTP patients.

The efficacy of sirolimus in treating immune-mediated thrombocytopenia is attributed to its role as an mTOR inhibitor, which modulates lymphocyte activity, a key factor in the pathogenesis of ITP [21]. Importantly, sirolimus has been shown to restore the balance of various immune cell types, including Tregs, Th2, and Th17 cells, which are often disrupted in autoimmune conditions like ITP [22]. In an open-label, prospective clinical trial involving 86 patients with RTP [23], 40% achieved CR by the third month of treatment. After 6 months, 41% of patients maintained CR, and the overall response rate remained at 65% at the 12-month follow-up. The study also observed a decrease in the proportion of Th2 and active Th17 cells, while the percentage of Treg cells increased. These findings suggest that sirolimus may help reestablish peripheral immune tolerance in ITP patients. Common occurrences in SLE include both numerical and functional deficiencies of Tregs [24] as well as the activation of the mTOR pathway. It is reported that T cells in SLE patients exhibit mitochondrial hyperpolarization (MHP) and adenosine triphosphatase (ATP) depletion, leading to a propensity for pro-inflammatory death [25]. The mTOR pathway, acting as a sensor for MHP, plays a crucial role in T cell activation in SLE. In our study, the increase in Tregs and platelet counts observed aligns with the known role of the mTOR pathway in immune thrombocytopenia [26], especially in SLE patients [27]. Additionally, our study observed a reduction in CD3+, CD8+, and CD4+ cells, as well as a decrease in cytokine levels of IL-17A and IL-8 following sirolimus treatment. This aligns with previous reports indicating that sirolimus can reduce the levels of IL-17 and other inflammatory factors in SLE patients, which is consistent with its known immunomodulatory effects [28]. In addition, levels of activated Th17 cells were reported to be elevated in ITP patients, and produce large amounts of IL-17, IL-21, and IL-22 [29]. These studies support our findings. However, in this study, we found no significant change in the number of B cells before and after treatment of sirolimus. Research indicates that sirolimus can stimulate B-cell activating factor (BAFF)-induced B-cell proliferation and reduce the production of autoantibodies [30]. In vitro studies have shown that sirolimus can block the proliferation of anti-Sjogren’s syndrome B antibodies (anti-SSB antibodies) and inhibit immunoglobulin production [18]. This suggests that sirolimus may have a broader application in various CTDs, where conventional therapies might not be as effective.

Interestingly, in our study, there was a case considered to be thrombocytopenia secondary to antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) associated with SLE, where sirolimus treatment was also effective. This aligns with reports suggesting that the mTOR pathway plays a role in the development of vasculopathy in APS [31]. In kidney transplant recipients with APS, treatment with sirolimus has been associated with a lack of recurrence of vascular lesions and decreased vascular proliferation, as compared to patients not receiving sirolimus [32]. These findings suggest that combining sirolimus with anticoagulants may not only improve the prognosis of APS but also prevent new thrombosis.

Limitations

Some limitations should deserve our attention. First, the single-centre, retrospective nature, small sample size, and short observation period may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should focus on multi-centre, large-scale clinical trials to validate or refute these findings. In addition, the lack of assessment of bleeding scores and health-related quality of life during follow-up was also a limitation of this study. Additionally, exploring the long-term effects of sirolimus and its combination with other immunosuppressants in a broader range of CTDs would be valuable. Investigating the specific mechanisms through which sirolimus affects different immune cell types could also provide deeper insights into its therapeutic potential and help tailor treatment strategies for individual patients.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the field of CTD and immunotherapy by demonstrating the effectiveness of sirolimus in a specific subset of CTD-RTP patients. It highlights the potential of sirolimus not only in reducing thrombocytopenia but also in modulating the immune system. This study finds that sirolimus increases Treg cells and platelet counts, but decreases CD3+, CD8+, and CD4+ cells, as well as suppresses the levels of cytokines IL-8 and IL-17A. These findings may provide a basis for the use of sirolimus in clinical practice, making it a promising another agent for refractory or relapsed CTD-RTP.