Introduction

Autoimmune bullous disorders (AIBD) affecting skin and mucous membranes are a heterogeneous group of diseases resulting from production of autoantibodies. An autoimmune reaction is predominantly directed against structural proteins (desmosomal proteins in pemphigus diseases and dermal-epidermal junction proteins in pemphigoid diseases, including epidermolysis bullosa acquisita) or enzymes (dermatitis herpetiformis – DH) [1, 2]. Early diagnosis of AIBD is crucial to initiate appropriate treatment, which is frequently intensive and may even have lethal side effects. It is worth mentioning that almost 30% of patients with pemphigus vulgaris went through more than 6 months of the diagnostic process and had visited more than four physicians [3]. Nowadays, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is still the main imaging diagnostic tool used to diagnose AIBD. DIF in our laboratory is based on detecting deposits composed of immunoglobulins (IgG, IgG1, IgG4, IgA, IgM) and complement component 3 (C3) when AIBD with autoimmunity to predominantly structural proteins are suspected clinically, or IgG, IgA, IgM and C3 when DH is considered clinically [4]. In routine laboratory workups, biochemical and molecular serum studies using ELISA or indirect immunofluorescence, preferably both based on multiplex approaches, should be used to precisely identify targets for autoimmunity.

Aim

The aim here was to assess the percentages of positive and negative DIF tests performed in individuals clinically suspected to suffer from AIBD in a single Central European referral laboratory department and to propose ways to improve the effectiveness of DIF in AIBD imaging diagnostics.

Material and methods

We assessed the positive and negative results of DIF over a 9-year period (2016–2024) in a single laboratory of the Central European referral department. Retrospective data based on all available records was analysed. Our study aimed to determine the number of positive tests and explore ways to enhance the effectiveness of DIF in AIBD diagnostics. The results were recorded as positive if the immunoreactants detected were compatible with AIBD. DIF was performed from non-lesional tissue biopsy with commercially available fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rabbit polyclonal antibodies against human IgA, IgM, IgG, and C3 (Dako, Denmark) and FITC-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibodies against human IgG subclasses namely IgG1 and IgG4 (Sigma, USA). In this study, we excluded from analysis patients who exhibited isolated IgM deposits in DIF, regardless of the pattern. However, recent German data provided the first evidence that IgM pemphigoid diseases exist [5]. Of note, we have not revealed/found any patients with isolated linear IgM deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction.

Two independent evaluators performed each assessment using a microscope with a short-arc mercury lamp (BX40, Olympus, Japan) or blue light-emitting diode technology-operated microscopy (EuroStar III Plus microscope, Euroimmun, Germany) [4, 6]. We analysed the total number of results, the numbers of positive and negative results year by year, and the distribution of results according to the unit that submitted the material for testing. Other units refer to medical facilities apart from the Dermatology Hospital Unit and the Dermatology Outpatient Clinic.

A total of 1985 consecutive tests (a full set of antibodies against all immunoreactants mentioned above) were included in the study. Each test was performed on one unique biopsy from patients suspected by clinicians of potentially having AIBD.

Statistical analysis

The Pearson correlation coefficient and χ2 tests were used for statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13 (StatSoft Polska, Krakow, Poland). A significance level of α = 0.05 was set, meaning that results were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Results

We found that approximately one-third of the DIF tests were positive with a total rate of 30.88% over 9 years and that the percentage of positive DIF results varied from year to year (from 26.22% in 2016 to 38.89% in 2023). The percentage of positive DIF results fluctuated slightly over the analysed years. However, the correlation between the particular year and the percentage of positive results in that year was not statistically significant (R = 0.7034; p = 0.0516; Pearson correlation coefficient). Table 1 presents the distribution of positive and negative DIF results for each year and in total, divided into the pemphigoid group (367 results, 60.56% of positive results), the pemphigus group (98 results, 16.17%) and dermatitis herpetiformis (141 results, 23.27%). Altogether, the pemphigoid group patients were the most frequent, followed by DH patients, whereas the pemphigus group patients were the least frequent (Table 1).

Table 1

Detailed characteristics of positive and negative results of DIF in each year and in total

Moreover, we analysed data based on the unit type responsible for the patient’s treatment, namely the outpatient clinic and the hospital ward. We found a statistically significant difference between unit types in terms of material submitted for analysis. The percentage of positive DIF results was higher in the outpatient clinic than in the hospital ward (33.7% vs. 22.9%; p < 0.0001; χ2 test) (Table 2).

Discussion

A similar study to ours was conducted in Boston (Massachusetts, USA) over an 8-year period (2012–2020) [7]. In the study cited, 2050 biopsies were tested with DIF and only 367 (17.9%) were positive. However, we must emphasise that a wide range of clinical suspicions were tested using DIF in that study (not only immunobullous diseases but also vasculitis, lupus erythematosus and other connective tissue diseases, lichen planus, porphyria). We also found some unexpectedly positive DIF results. A noteworthy patient with a positive DIF result that was compatible with a pemphigus disease but not SCLE or psoriasis vulgaris, suggested initially by a clinician, is shown in Figure 1. In this case, DIF was performed only after H + E histology revealed features compatible with pemphigus foliaceus. Using data presented in the American study, we calculated the percentage of positive results in the case of bullous disorder suspicion, which was 16.57%. In our study, the percentage of positive results was much higher (30.88%), which may be due to a more precise patient selection and lower availability of the method among physicians in Poland. In our department, every test was performed after a consultation with a dermatologist, significantly increasing the accuracy of patient selection. To the best of our knowledge, the study cited was the only one to assess statistical characteristics of DIF testing results in bullous disorders. Our study is the first to focus exclusively on AIBD.

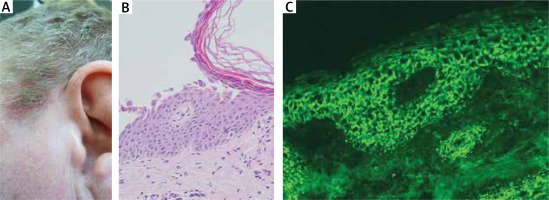

Figure 1

A noteworthy patient with a positive DIF result. A middle-aged male presented with scalp and truncal lesions, including a shallow erosion covered with greasy greenish crusts on the temporal area of the scalp at the border between hairy and glabrous skin (A). H + E histology showed a subgranular separation with numerous acantholytic cells (original objective magnification: 20×) (B). DIF, performed after the result of H + E histology was available and visualized with blue light-emitting diode technology-operated microscopy, exhibited IgG1(+), IgG4(+++) (C) and C3(+) pemphigus deposits (original objective magnification: 40×). Multiplex ELISA revealed an elevated level of IgG antibodies to DSG1 (level 4.79, cut-off level 1.00) but not DSG3. ANA testing revealed IgG antibodies having granular-cytoplasmic staining pattern at a titre 1 : 320. IgG antibodies against ENA (RNP/Sm, Sm, SS-A, SS-B, Scl-70, and Jo-1) were within the normal range with ELISA. Therefore, pemphigus foliaceus, but not psoriasis vulgaris suggested initially and SCLE suggested later by a dermatologist from the dermatology department of a non-university hospital, was eventually diagnosed

Furthermore, we found a slight, albeit statistically insignificant, improvement in the percentage of positive results over the years. This may be a result of continuous staff turnover due to the teaching nature of the centre. Still, every clinical staff member, whether a dermatologist or a dermatology trainee, should acquire the necessary professional skills to order DIF testing when AIBD is suspected. This may be challenging because AIBD is considered rare not only by the general medical community but also by dermatologists. In this respect, the supervision of an experienced dermatology specialist who is a willing teacher cannot be overestimated.

We also evaluated units that sent material for DIF testing. Surprisingly, a higher percentage of positive results was found in the outpatient clinic group compared to the hospital ward group. It can result from the wider diagnostic path followed in the hospital and more complicated cases of patients admitted to the ward in terms of diagnostic difficulty. Therefore, according to our data, outpatient clinics can be effective institutions in diagnosing AIBD, and their effectiveness is statistically higher than that of hospitals.

Moreover, we would like to discuss the negative results and their significance. Sometimes, blisters do not provide any basis for clinically suspecting bullous pemphigoid, as we know nonbullous bullous pemphigoid exists. On the other hand, what is even more frequent is that blisters can be the result of infectious skin disorders, while AIBD should be excluded as it crucially impacts the treatment we choose. Good examples of such situations are bullous drug eruptions, erythema multiforme, bullous lichen planus, bullous mastocytosis, epidermolysis bullosa, impetigo, and even bullous variety of/bullous scabies [8]. Moreover, DIF should be performed properly. Notably, some clinicians initiate treatment for patients suspected of having AIBD before performing any laboratory test. Some undiagnosed patients even receive repeated courses of parenteral glucocorticosteroids, leading to fluctuations in disease activity. Only when the response to therapy is unsatisfactory are such individuals referred for appropriate imaging and biochemical and molecular diagnostics. This practice is problematic because it increases the risk of false negative results, especially when the clinical activity of the disease is mild [9].

From a procedural standpoint, biopsy material should not be divided into two parts, one for H + E histology and the other for DIF as this can damage tissue architecture, rendering the material non-diagnostic for both examinations. Therefore, it ought to be stressed that two separate biopsies should be taken. The biopsy for DIF should be taken from perilesional uninvolved tissue from all AIBD, whereas the biopsy for H + E histology should be taken from lesional tissue.

There were certain limitations to our study that should be mentioned. It was a single-centre study conducted in one laboratory. On top of that, each DIF was assessed by the same two experienced evaluators performing mutual checking. Still, potential human biases cannot be excluded. In addition, DIF has its limitations. It highly depends on the site where the biopsy was taken. However, the site was always chosen by a specialised dermatologist or an experienced dermatology resident. Despite this, it should be kept in mind that the evaluation of the severity of immunoreactants deposition is done using the grading scale only. Also, the DIF reading does not provide information about autoimmunity to specific targets.

Relating clinical images and DIF results would be valuable for teaching purposes. Unfortunately, this was a retrospective study, and as we do not routinely take photographic documentation of patients or store DIF ordering forms, this aspect had to be excluded from our study design. Nonetheless, we noted that among patients with negative DIF readings, a chronic, itchy, and unspecified disseminated rash (ICD-11 Coding Tool code EA8Z) was a common clinical diagnosis entered on printed DIF ordering forms. Of note, pruritus can be a feature of AIBD [10]. Conversely, we also recall patients with positive DIF readings inconsistent with initial clinical suspicions. Such a patient is depicted in Figure 1. Also, a patient had a clinical diagnosis of oral lichen planus written on the DIF ordering form, in whom positive DIF readings were compatible with the oral mucous membrane pemphigoid. In yet another patient, positive DIF readings in connection with the clinical data and results of serum immunological tests enabled the diagnosis of drug (indapamide)-triggered pemphigus foliaceus, but not SCLE suggested by a referring dermatologist.

It has been claimed that immunohistochemistry on paraffin sections for detecting tissue deposits of not only IgG but also IgG4 may be an alternative to DIF in diagnosing AIBD [11, 12]. Moreover, there were efforts to perform DIF on paraffin sections after proteinase digestion instead of frozen ones [13]. However, we believe that DIF performed on perilesional frozen tissue obtained from untreated individuals, in laboratories with appropriate equipment and by skilled personnel, is an unsurpassed imaging technique for diagnosing AIBD mediated by IgG- and IgA-driven autoimmunity. H + E histology of lesional tissue cannot reveal the autoimmune nature of AIBD; nevertheless, it can provide helpful hints for the clinician that performing DIF is necessary to diagnose the patient in question, as in our case depicted in Figure 1 [14].

Conclusions

DIF should be performed rationally, and almost one-third of positive results should be regarded as a good value compared to other studies on this subject. To improve this percentage, specialised units ought to be maintained to keep up with the constant development of knowledge and experience in AIBD [15, 16]. On the other hand, we would like to emphasise the significant value of negative results where laboratory data exclude some diagnoses. Thus, negative results cannot be perceived as mistakes. To illustrate this issue, practising dermatologists send the biopsies for DIF obtained predominantly from elderly individuals complaining of pruritus accompanied by a disseminated non-blistering rash to exclude pemphigoid diseases. The negative DIF reading, together with negative biochemical-molecular tests for identification of target antigens, excludes AIBD and, as such, provides clinically relevant data. For laboratory effectiveness, a perfect command/understanding of clinical dermatology by practising dermatologists is crucial when considering DIF.