Introduction

Skin wound healing is a complex, dynamic, and highly regulated process. Normal wound healing is crucial to maintaining the skin’s barrier function. The wound healing process is affected by multiple factors, including systemic and local conditions. Different types of cells, extracellular matrix, cytokines, and signalling pathways are interrelated and participate in the wound healing process to achieve the restoration of skin integrity and basic functions. Even under the best conditions, wound healing cannot return to the state before the injury. If any obstacle occurs in any link, wound healing will be affected and the wound will not heal. The temporal definition of refractory body surface wounds has been reported inconsistently in the literature, and there is currently no unified definition. At present, the main cause of chronic wounds in our country/China has shifted from trauma to chronic diseases, and the incidence rate has been increasing year by year. Chronic wounds are often difficult to treat, require a long time, and are expensive. It is a chronic disease that seriously endangers the physical and mental health of people, reduces the quality of life, and even incapacitates work/causes incapacity to work. It increases the burden on families and society and takes up a lot of medical resources. It is the focus and difficulty of domestic and foreign research.

Chronic refractory wounds refer to wounds that cannot undergo normal repair procedures and cannot be restored to anatomical and functional integrity after repair by autologous repair functions. Clinically, it usually refers to a wound that has not healed and does not tend to heal after more than 1 month of formal treatment [1]. Wound repair is a complex and dynamic process in which a variety of cells participate and coordinate with each other to produce biochemical reactions to repair damaged tissue [2]. Wound repair mainly goes through four stages: coagulation stage, proliferation stage, inflammation stage, and remodelling stage [3]. When trauma occurs, cells and related factors involved in repair in the body are activated, platelets gather at the injured site under chemotaxis, and the formation of fibrin clots further promotes haemostasis. Due to the stimulation of trauma, capillary permeability increases, and inflammatory cells enter the wound area to regulate the inflammatory response and exert an anti-infective effect. During this process, keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and immune cells are activated, and under the stimulation of various growth factors, new blood vessels form in the wound, cell-matrix precipitates, fibrous tissue proliferates, and epithelializes. The collagen matrix is formed by the extracellular matrix secreted by activated fibroblasts, filling and remodelling the wound [4]. Currently, the methods commonly used in the clinical treatment of chronic difficult-to-heal wounds mainly include moist healing dressings, negative pressure sealing drainage, growth factors, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, traditional Chinese medicine treatment, infrared ray, surgical skin grafting or flap transplantation, and autologous platelet derivatives represented by PRF [5, 6]. Domestic research on treatment methods mainly focuses on tissue reconstruction and wound repair. The application of traditional Chinese medicine inherits Chinese traditional medical methods. It is combined with modern dressing technology and different combinations of traditional Chinese medicine. The fundamental treatment idea is to remove saprophytic muscle and regenerate muscle, remove the basal necrotic tissue in difficult-to-heal wounds, and establish a good foundation for wound healing. However, due to the impact of traditional Chinese medicine applications such as unsatisfactory infection control, it has not been used as the main treatment method [7]. In recent years, the role of autologous biomaterials in wound repair has been increasingly reported, especially platelet derivatives. The clinical application is represented by platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), which has become one of the most promising methods for the treatment of chronic difficult-to-heal wounds [8].

The concept of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) was first proposed by Choukroun in 2000 [9]. It is a gel rich in growth factors, platelets, and leukocytes, which is produced by centrifugation of venous blood. Its loose mesh-like three-dimensional structure is conducive to the storage and continued function of cells and factors, and due to the regulation of inflammatory cells, PRF exerts a better anti-infection effect, and activated platelets secrete a large number of growth factors to promote tissue repair. Therefore, PRF plays an important role in the repair of chronic refractory wounds [10]. In addition, the preparation process of PRF is simple and cheap, without anticoagulant, and the coagulation cascade reaction is initiated immediately after the blood comes into contact with the test tube [11]. After the start of the coagulation phase, thrombin in the circulation is converted from prothrombin to fibrinogen during centrifugation, and a fibrin clot is obtained in the middle of the test tube where the platelet concentrate is stored [12]. In the PRF obtained by centrifugation, platelets are compressed and can be naturally activated to slowly and continuously release various growth factors (GF), such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and insulin-like growth factor, etc. [13]. The three-dimensional structure of fibrin protects growth factors from proteolysis, allowing them to be slowly secreted and exert their long-term effects, with growth factor concentrations peaking on days 7 to 14 and continuing to remain high for approximately 28 days [14]. Current research on PRF for the treatment of chronic fire-resistant wounds is mainly focused on animal models and is currently used clinically in oral repair and fracture repair [15]. Therefore, PRF has gradually received attention in the process of chronic wound repair due to its high concentration of growth factors, autologous source, safety and effectiveness, and low cost.

A hallmark of canonical Wnt signalling is the accumulation and translocation of the adherent junction-associated protein β-catenin in the nucleus [16]. The β-catenin destruction complex is composed of Axin, Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) protein, Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 (GSK3), and Casein Kinase 1α (CK1α). CK1α and GSK3 in this complex can phosphorylate β-catenin, and the phosphorylated form of the involute is ubiquitinated by E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase and subsequently proteolyzed by the proteasome complex [17]. Wnt signalling is involved in every subsequent stage of the healing process, from controlling inflammation and programmed cell death to mobilizing the stem cell pool at the wound site [18]. In mammalian organs and tissues with limited regenerative capacity, Wnt signalling remains required for repair processes [19]. Inhibiting Wnt signalling during skin injury prevents the formation of epithelial appendages, including hair and sweat glands, which results in significant scarring of the epidermis [20].

Aim

This study aimed to explore the effect of PRF on the repair and healing of chronic refractory wounds in rats by regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway.

Material and methods

Main instruments and reagents

IL-6 (lot no.: P1042), IL-1β (lot no.: P1037), TNF-α (lot no.: P1003), SOD (lot no.: P1042), MDA (lot no.: P 1040) and VEGF (batch no.: P1012) Enzyme-Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA) kit was purchased from Shanghai Shanran Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; Wnt1, β-catenin, GSK-3β, and β-actin primers were designed and compounded by Shanghai Yingjie Biotechnology Co., Ltd. RT-PCR kit (lot no.: D7277S), Wnt1 (lot no.: AF8349), β-catenin (lot no.: AC106), GSK-3β (lot no.: AF1531) and GAPDH (batch no.: AF1186) were brought from Shanghai Biyuntian Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Real-time quantitative Agilent PCR instrument was purchased from Agilent Technologies, USA.

Experimental animals

50 SPF grade SD male rats, 6 to 7 weeks old, with body weight of 180 to 200 g, were adaptively fed for 1 week before the experiment, and fed freely. They were used in the experiment after they were in good health. The entire experiment was conducted in accordance with animal ethics standards.

Establishment of the rat model of chronic refractory wounds

Forty SPF rats were randomly selected. A rat chronic refractory wound model was prepared with the help of pressure device. Before the experiment, the rats were first anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (80 mg/kg), and the rats to be modelled were placed on their sides and fixed on the foam mattress. An animal-specific shaving instrument was used to apply pressure to the exposed location (the gracilis muscle on the right side of the thigh was selected). A rat model of chronic refractory wounds was prepared by simulating the physiological response of ischemia-reperfusion. The pressure device applied pressure to rats to simulate the “ischemia” process (lasting 2 h) and released the pressure to simulate the “reperfusion” process (lasting 0.5 h). The complete “ischemia-reperfusion” cycle to prepare the rat model of chronic refractory wounds took 2.5 h. The pressure parameter was set to 34.7 kPa. Six cycles were performed on all rats. The rat model of chronic refractory wounds is considered to have been successfully prepared if obvious pressure erythema with a diameter of about 1 cm appears in the prepared rats and does not fade after being pressed for 30 min. The remaining 10 rats served as the blank control group. Only the magnetic device was inserted into the same surgical site without applying pressure.

Experimental grouping

Rats that were successfully modelled were randomly divided into the model group, PRF group (platelet-rich fibrin external gel), positive control group (recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor external gel), PRF + XAV-939 (β-catenin inhibitor intraperitoneal injection) group, with 10 rats in each group; another 10 rats without modelling were chosen as the blank control group.

PRF preparation

The venous blood of 8 volunteers was extracted from vacuum blood collection tubes without anticoagulants, quickly placed in a centrifuge, and immediately centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 10 min. After centrifugation, the blood in the test tube was divided into three layers. PRF was located between the deep red blood cell fragments in the bottom layer and the light yellow platelet-poor plasma clarification liquid in the top layer, which was in the form of a light yellow gel. A sterile syringe needle was used to extract the gel strip from the blood collection tube. Then, the tail of the PRF was trimmed and a small amount of red blood cell component was retained, thus completing the preparation.

Observation of wound healing

Wound area and healing rate: photos of the wound were taken immediately after surgery and on days 3, 7, and 14. When taking photos, a scale was used to measure the length of the horizontal and vertical axes of the wound. The wound graphics were drawn along the edge of the wound with transparent grid paper, and the not-healed area of the wound was counted using Image J software after taking photos. The formula for calculating the healing rate is as follows: healing rate = (original wound area – unhealed area)/original wound area × 100%.

HE staining

On days 3, 7, and 14 after surgery, the wound edge tissue was removed and fixed in 4% aldehyde solution, embedded in routine paraffin, segmented, and dyed with hematoxylin and eosin after dewaxing and hydration. Five 200× fields of view were selected under a light microscope to observe the inflammatory response of the wound, and image analysis software was used to measure the thickness of the granulation tissue.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) detection

After treatment, the wound tissue was taken, and fixed in a 10% neutral formalin solution for 24 h, and paraffin sections were made for immunohistochemical staining and detection of CD34 expression in rat granulation tissue.

Enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) detection

The ELISA kit was used to detect the TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels of the serum of rats in each group. The kit was operated according to the instructions of the kit and detection was performed with the help of a microplate reader.

Western Blot detection

The protein expression levels of Wnt1, β-catenin, GSK-3β, and c-myc in the rat wound tissues of each group were found. The total protein of the rat wound tissues in each group was collected, and SDS buffer was added to inactivate it at high temperatures. After gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), the protein was placed on a PVDF membrane, and hatched for 60 min. Primary antibodies Wnt1 (1 : 1000), β-catenin (1 : 2000), GSK-3β (1 : 1000), and c-myc (1 : 1000) were added. It was let stand for 12 h at 4°C, the primary antibody was discarded, and the membrane was washed 3 times with TBST for 5 min each time. After color development, β-actin was used as the internal reference to calculate the gray-scale ratio of each protein.

Statistical analysis

The data in this research were analysed by SPSS 26.0 software, including counting data and measurement data. The former was delegated by “[n (%)]” and “χ2” was used for testing, and the latter was represented by mean ± standard deviation (x ± SD) and took “t” to carry out the test, if p < 0.05, it can be confirmed that the data difference was significant.

Results

Comparison of wound healing rates in rat models of chronic refractory wounds in each group

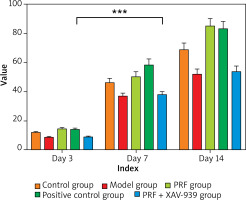

The wounds of rats in each group healed to a certain extent over time (Figure 1, Table 1). Compared with the normal control group, the wound healing rate of rats in the model group was lower at each time point (p < 0.05). Compared with the model group, the wound healing rate of rats in the PRF group and positive control group was higher at each time point (p < 0.05). Compared with the PRF group, the wound healing rate of rats in the PRF + XAV-939 group was reduced at each time point (p < 0.05). There was no difference in the wound healing rate between the PRF group and the positive control group. Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference in the wound healing rate between the model group and the PRF + XAV-939 group (p > 0.05).

Table 1

Statistical table of wound healing rates in each group (%, x ± SD)

| Group | Day 3 | Day 7 | Day 14 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 10) | 12.05 ±0.62a | 46.25 ±3.05a | 68.85 ±4.60a |

| Model group (n = 10) | 8.75 ±0.65b | 37.20 ±1.84b | 52.26 ±3.25b |

| PRF group (n = 10) | 14.56 ±0.88a | 60.25 ±3.55a | 85.25 ±5.02a |

| Positive control group (n = 10) | 14.15 ±0.86a | 58.52 ±4.05a | 83.22 ±5.05a |

| PRF + XAV-939 group (n = 10) | 9.02 ±0.50b | 38.01 ±2.05b | 53.86 ±3.80b |

Histopathological observation of wound granulation in each group

Compared with the normal control group, the granulation tissue of the rats in the model group was more seriously damaged, and infiltrated by a large number of inflammatory cells, and the collagen fibres were loosely arranged and unevenly distributed. Compared with the model group, the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the granulation tissue of rats in the PRF group and the positive control group was reduced, and the collagen fibres were tightly arranged. Compared with the PRF group, there was no significant difference in the degree of granulation tissue damage in rats in the PRF + XAV-939 group.

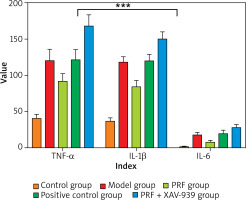

Comparison of serum inflammatory factor levels in various groups of chronic refractory wound rat models

Compared with the normal control group, the serum TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels of rats in the model group were significantly increased (p < 0.05). Compared with the model group, the serum TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels of rats in the PRF group and positive control group were significantly reduced (p < 0.05). Compared with the PRF group, the serum TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels of rats in the PRF + XAV-939 group were higher (p < 0.05). The serum factor levels between the rats in the PRF group and the positive control group were relatively close, but there was no statistical significance difference in the comparison between the serum factors between the model group and the PRF + XAV-939 group (p > 0.05) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2

Comparison of serum inflammatory factors among rats in each group x ± SD [ng/ml]

| Group | TNF-α | IL-1β | IL-6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 10) | 40.56 ±5.50a,b | 37.15 ±4.12a,b | 2.15 ±0.35a,b |

| Model group (n = 10) | 120.08 ±15.66b | 118.25 ±7.55b | 18.22 ±3.20b |

| PRF group (n = 10) | 92.25 ±10.15a | 84.32 ±8.55a | 8.25 ±2.05a |

| Positive control group (n = 10) | 121.60 ±13.58b | 120.25 ±8.52b | 20.05 ±4.08b |

| PRF + XAV-939 group (n = 10) | 168.25 ±15.05a,b | 150.40 ±9.55a,b | 28.22 ±3.80a,b |

Detection of CD34 expression in wounds by IHC

Compared with the normal control group, the ratio of CD34-positive cells in rats in the model group was reduced (p < 0.05). Compared with the model group, the ratio of CD34-positive cells in the PRF group and positive control group was increased (p < 0.05). Compared with the PRF group, the ratio of CD34-positive cells in the PRF + XAV-939 group was decreased (p < 0.05). There was no statistical significance difference in the comparison of the above indicators between the rats in the PRF group and the positive control group, and there was no statistical significance difference in the comparison between the above indicators in the model group and the PRF + XAV-939 group (p > 0.05) (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3

Statistical table of CD43 positive cell count (x ± SD)

| Group | Day 3 | Day 7 | Day 14 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 10) | 118.52 ±8.85b | 110.59 ±6.58b | 149.53 ±9.82b |

| Model group (n = 10) | 102.75 ±8.25b | 108.25 ±6.55b | 132.28 ±12.28b |

| PRF group (n = 10) | 278.80 ±15.43a | 268.37 ±10.55a | 295.67 ±16.53a |

| Positive control group (n = 10) | 266.90 ±14.15a | 276.22 ±12.58a | 305.59 ±13.56a |

| PRF + XAV-939 group (n = 10) | 176.58 ±12.15a,b | 210.55 ±15.10a,b | 233.58 ±15.59a,b |

Protein and mRNA expression of Wnt1, β-catenin, GSK-3β, and c-myc in wound tissue of chronic refractory wound rat models in each group

Compared with the normal control group, the protein expression levels of Wnt1, β-catenin, and c-myc in rats in the model group were significantly reduced, and the expression level of GSK-3β protein was significantly increased (p < 0.05). Compared with the model group, the protein expression levels of Wnt1, β-catenin, and c-myc in rats in the PRF group and positive control group were significantly increased, and the expression level of GSK-3β protein was significantly decreased (p < 0.05). Compared with the PRF group, the protein expression levels of Wnt1, β-catenin, and c-myc in rats in the PRF + XAV-939 group were significantly reduced, and the expression level of GSK-3β protein was significantly increased (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the PRF group and the positive control group, and there was no significant difference between the model group and the PRF + XAV-939 group (p > 0.05) (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Table 4

Expression of Wnt1, β-catenin, GSK-3β, and c-myc proteins in wound tissues of rats in each group (/β-actin, x ± SD)

| Group | Wnt1 | β-catenin | c-myc | GSK-3β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 10) | 1.25 ±0.16b | 1.34 ±0.21b | 1.86 ±0.26a,b | 0.51 ±0.09a,b |

| Model group (n = 10) | 1.15 ±0.16b | 1.25 ±0.18b | 1.05 ±0.12b | 1.66 ±0.28b |

| PRF group (n = 10) | 2.05 ±0.32a | 1.89 ±0.33a | 2.20 ±0.32a | 0.94 ±0.15a |

| Positive control group (n = 10) | 2.01 ±0.14a | 1.91 ±0.28a | 2.16 ±0.33a | 0.96 ±0.13a |

| PRF + XAV-939 group (n = 10) | 1.13 ±0.15b | 1.22 ±0.16b | 1.07 ±0.13b | 0.53 ±0.10a,b |

Discussion

Chronic refractory wounds refer to wounds that cannot undergo normal repair procedures and cannot be restored to anatomical and functional integrity after autologous repair. Clinically, it usually refers to a wound that has not healed and has no tendency to heal after more than 1 month of formal treatment. Wound repair is a complex and dynamic process in which a variety of cells participate and coordinate with each other to produce biochemical reactions to repair damaged tissue [21]. When trauma occurs, cells and related factors involved in repair in the body are activated, platelets gather at the injured site under chemotaxis, and the formation of fibrin clots further promotes haemostasis. Due to the stimulation of trauma, capillary permeability increases, and inflammatory cells enter the wound area to regulate the inflammatory response and play an anti-infective role. In the process, keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and immune cells are activated. Under the stimulation of various growth factors, new blood vessels form in the wound, cell-matrix precipitates, fibrous tissue proliferates, and epithelializes; the collagen matrix is formed by the extracellular matrix secreted by activated fibroblasts, filling and remodelling the wound [22].

As a second-generation platelet concentrate product after high-concentration platelet plasma (PRP), PRF has more outstanding advantages than PRP. First of all, the preparation of PRF does not require the addition of any additives, which avoids the risk of immune rejection reactions induced by foreign substances in the body, and its safety is more guaranteed than PRP [23]. Secondly, PRF has a loose grid three-dimensional structure, and the fibrin matrix is arranged in a grid-like three-dimensional staggered manner, which is conducive to the storage and sustained release of cytokines and can provide a place for the biochemical activities of cells. Since anticoagulants and allogeneic thrombin are added to PRP during the preparation process, it accelerates the polymerization of fibrinogen and forms a fibrin network with a rigid structure and lack of elasticity, which is not conducive to the storage of cytokines and cell activities [24]. Finally, the mode of cytokine release by PRF is better than that of PRP. Since anticoagulants and allogeneic thrombin are added to PRP, the platelets in PRP are instantly activated. After platelets are activated, the released cytokines further promote the release of cytokines in platelet stimulation. Therefore, PRP has a higher concentration of cytokines in the early stage, but less release in the later stage, and the release of cytokines is not lasting. PRF has the advantage of a loose grid three-dimensional structure, which allows relatively sustained release of cytokines and growth factors and maintains a higher concentration of cytokines and growth factors during the wound repair process, which is more conducive to promoting wound healing [25].

Studies have found that the α granules of platelets in PRF can release a variety of growth factors, including PDGF, VEGF, FGF, TGF, IGF, etc. [26], which play an important role in wound repair and make up for the lack of growth factors in chronic wounds. In the process of chronic wound repair, growth factors play a role in activating inflammatory cells, promoting the formation of new blood vessels, accelerating cell proliferation, differentiation, and promoting the growth of granulation tissue, which enhances the repair function of chronic wounds and promotes wound healing [27]. After platelets in PRF are activated, the duration of growth factor release varies, with the release of TGF-β1 peaking on day 7 and the main release of VEGF occurring between days 3 and 7. The main release of IL-1β occurs between days 1 and 7. Sustained release of IGF-1 and PDGF-AB during the first 3 days after activation [28, 29]. In this experimental study, the PRF group drew blood to prepare PRF gel and covered the wounds of rats to maintain a higher concentration of growth factors on the wounds. Inflammation is a reaction caused by the body’s injury and is an important factor affecting wound healing. Early inflammatory response is the body’s means of fighting infection and trauma. It can remove harmful factors and damaged tissue and promote tissue repair. However long-term inflammation can hinder tissue repair. PRF can release a variety of cytokines involved in inflammatory regulation, which jointly regulate immune responses. A dynamic balance between the concentrations is maintained, the inflammatory response of the wound is controlled, and wound repair is accelerated [29].

Wound healing involves a variety of regulatory factors and cell signalling pathways, among which the Wnt signalling pathway is closely related to wound repair. Research shows that during skin development, the Wnt signalling pathway appears earliest and is also the most important signalling pathway in skin damage repair. The Wnt signalling pathway is also essential in the regulation of hair growth. It can promote hair growth, among which Wnt1 is the key protein that activates and regulates the Wnt signalling pathway. It can enter the nucleus, leading to the expression of target genes such as CDK4 and changing the cell cycle [29]. When skin is damaged, the Wnt signal released by surrounding cells initiates the nuclear translocation of β-catenin, causing it to form a transcription complex with DNA-binding proteins such as Lef1/TCF. It also initiates the transcription of Wnt target genes and the process of cell proliferation and differentiation to promote skin repair. The decrease in β-catenin protein expression will increase the expression of downstream GSK-3β protein, which will reduce the skin’s self-repair ability and is not conducive to wound healing [30].

This study revealed the effect of PRF on wound healing in rats and the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. This experiment recorded and calculated the wound area at different times. Through analysis, it was found that the wound healing rate of rats in the 7 to 14-day PRF group was higher than that of the control group. It was initially shown that PRF can effectively promote wound healing in diabetic rats, and can promote the reduction of inflammatory cell infiltration and make collagen fibres densely arranged.