INTRODUCTION

It is known that outdoor activities, tanning, sunbathing, water and non-water sports are associated with sunburn [1]. Sunburn is an acute inflammatory skin reaction occurring due to extended exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun or artificial sources [2]. Sunburns might appear inconsequential, but they promote photoaging, photoallergy, phototoxic reactions, and carcinogenesis, including life-threatening melanomas [3, 4]. Alongside with physical factors, male gender, white race, sun sensitive skin type, and use of some medications are associated with an increased risk of sunburn [1, 5].

Preventing sunburn is the cornerstone of this problem [6, 7]. Despite the accessibility of educational initiatives and the relative ease of implementing preventive strategies, a substantial number of individuals continue to seek medical attention for sunburn in emergency departments or manage the condition through self-medication at home [8]. Symptomatic management of sunburn includes the use of cold tap water compresses, oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and topical agents such as diclofenac sodium gel, aloe vera gel, water-based lotions, or petroleum jelly [2].

Although sunburn is usually not dangerous, its frequency among the population requires expanding the list of drugs for topical treatment of this pathology. Based on the participation of free radicals in the pathogenesis of UV radiation damaging effects on the skin, as well as taking into account the protective effect of antioxidants during photoaging and carcinogenesis [9], we drew attention to the heterocyclic antioxidant, ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate (EMHPS), which has high antiradical activity, regulates signaling pathways, provides cytoprotection, and has a low toxicity profile [10].

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of EMHPS gel in a model of acute UV-induced skin damage in laboratory animals.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Material

All reagents for biochemical analysis, gel-forming and auxiliary substances were manufactured by Merck KGaA (Germany). The EMHPS substance (an antioxidant, ATC code: N07XX) was obtained from Microchem LLC (Ukraine). 5% panthenol ointment (dexpanthenol, a wound healing agent, ATC code: D03AX03) was manufactured by Hemopharm AD (Serbia) and used as a reference drug.

The studied new EMHPS gel contained 5.0 g of the active substance, 0.5 g of sodium metabisulfite, 1.0 g of polyvinyl alcohol, 2.0 g of carbomer 940, 2.8 g of TRIS and distilled water to 100.0 g. It was prepared by laboratory technology.

Pathological model and experimental therapy

The 50 male Wistar rats weighing 185–215 g were kept in cages of 5 individuals on a standard laboratory diet and water ad libitum. They were housed in a temperature-controlled room with 12-hour light-dark cycles. The experiments were performed according to the principles of bioethics in accordance with the provisions of the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes (Strasbourg, 1986) and the European Union Directive 2010/10/63 EU. The research protocol was approved by the Commission on Ethical Issues and Bioethics of the Poltava State Medical University (No. 197, September 23, 2021).

A 5 cm2 area of the dorsal skin was depilated with a commercial cosmetic product based on potassium thioglycolate with the 3 min exposure [11] a day before UV irradiation. Rats were irradiated with a Cleo Compact Isolde UV lamp (Philips, Germany). A dose of UVA was 3.75 J/cm2 and a dose of UVB was 0.05 J/cm2. Immediately after irradiation and on every subsequent day, the skin of the test area was lubricated with 5% EMHPS gel at a dose of 125 mg/kg of body weight. 5% panthenol ointment, a reference preparation, was applied similarly at the same dose. The animals in the control group received an indifferent gel base as a vehicle. At 24, 48, and 72 hours post-irradiation, the animals were euthanized by terminal blood collection under general anesthesia, induced via intraperitoneal administration of sodium thiopental at a dose of 50 mg/kg (JSC Kyivmedpreparat, Ukraine) [12].

Morphological methods

Pieces of the skin of the test area from euthanized rats were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Inter-Syntez LLC, Ukraine), processed for standard histological examination and stained with hematoxylin and eosin [13]. Histological preparations were examined using an Olympus BX41 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Japan) equipped with a digital photomicrocamera and licensed software. Morphometric analysis included quantification of keratinocytes exhibiting dystrophic changes (per 100 cells), enumeration of inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils and macrophages) within a standard area of 0.01 mm², and measurement of epidermal thickness.

Biochemical assays

A 10% homogenate was prepared from the skin of the affected area in a 0.2 M Tris-HCl buffer solution (pH = 7.4). The content of malondialdehyde (MDA) in the skin homogenate was determined by a method based on the MDA ability to react with 1-methyl-2-phenyl-indole [14]. The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was measured by the kinetics of epinephrine autoxidation [15]. The activity of catalase was studied by the molybdate colorimetric assay [16]. The content of free hydroxyproline was determined by a colorimetric assay based on the reaction of pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid with paradimethylaminobenzaldehyde [17]. The concentration of glycosaminoglycans (GAG) total fraction was determined by the reaction of hexuronic acids with carbazole [18]. All optical density measurements were performed on a Ulab 101 spectrophotometer (China).

Statistical analysis

The obtained data were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (M ± SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. The Kruskal–Wallis H test was applied to assess differences between groups in the content of keratinocytes with dystrophic changes. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Histopathological changes in the skin

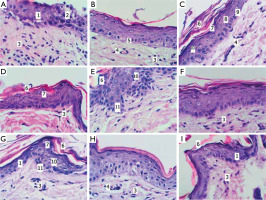

24 hours after UV irradiation in the control group, the boundaries between the epidermal layers were sometimes indistinct (fig. 1 A). The epidermis had an uneven thickness, there were areas of epidermal detachment. The granular layer was poorly expressed, mitoses were observed in the basal layer. A significant number of intraepithelial lymphocytes were observed. Epithelial cells frequently showed signs of hydropic degeneration. The papillary layer of the dermis contained a significant number of cellular elements, including fibroblasts (less often), lymphocytes and plasmocytes. Neutrophilic and eosinophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes were quite common. Blood vessels were mostly moderately engorged, with some showing leukostasis and congestion.

Figure 1

Structure of the rat skin 24 hours after remove UV irradiation in the controls (A), under the influence of EMHPS gel (B), and panthenol ointment (C); 48 hours after UV irradiation in the controls (D), under the influence of EMHPS gel (E), and panthenol ointment (F); 72 hours after the UV irradiation in the controls (G), under the influence of EMHPS gel (H), and panthenol ointment (I). Microscopical analysis at hematoxylin and eosin stain, 400×. 1 – areas of the epidermis with unclear boundaries between the layers of epithelial cells; 2 – partial desquamation of the epidermis; 3 – inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis; 4 – blood vessels in the dermis; 5 – mitoses in the basal layer of the epidermis; 6 – stratum corneum of the epidermis; 7 – granular layer of the epidermis; 8 – spinous layer of the epidermis; 9 – basal layer of the epidermis; 10 – epithelial cells with signs of hydropic degeneration; 11 – epidermal acanthosis

After 24 hours in the animals with topical application of EMHPS, the boundaries between the layers of the epidermis were clearly expressed (fig. 1 B). The epidermis had a relatively uniform thickness throughout. In the basal layer, there were single mitotic figures, a few intraepithelial lymphocytes. Epithelial proliferation with the formation of pseudopapillae was observed. The papillary layer of the dermis contained a moderate number of fibroblasts and hematogenous cells. The blood vessels predominantly demonstrated evidence of diminished vascular perfusion.

Under the influence of the reference preparation, 24 hours post-irradiation, the epidermal layers were distinctly delineated (fig. 1 C). The epidermis had a relatively uniform thickness throughout. A moderate number of epithelial cells in a state of hydropic dystrophy and a small number of intraepithelial lymphocytes were detected. In the papillary layer of the dermis there was a moderate number of cells with a predominance of fibroblasts. Blood vessels were present with moderate blood filling, some of them were full of blood.

At 48 hours after irradiation, in the control group, the boundaries between epidermal layers were largely well defined (fig. 1 D). In the epidermis, both areas of thinning and thickening due to the spinous and horny layers were found. Areas of acanthosis were evident. Mitoses and intraepidermal lymphocytes were found in the basal layer. Significant desquamation of the stratum corneum was noted. A moderate number of epithelial cells with signs of hydropic dystrophy were located mainly focally. The granular layer was well defined, parakeratosis and single intraepidermal cysts were found. In the epidermis, foci of cellular detritus with the presence of neutrophilic leukocytes were sometimes found. In the papillary layer of the dermis, a moderate number of cellular elements with a predominance of fibroblasts was found. Blood vessels were mainly moderately filled with blood.

During this time, under treatment with EMHPS gel, similar epidermal changes were noted as in controls, including focal thinning and thickening related to acanthosis and pseudopapillae formation (fig. 1 E). The stratum corneum exhibited localized hyperkeratosis with areas of significant desquamation. A moderate number of epithelial cells with signs of hydropic dystrophy were characterized by a focal location; intraepithelial lymphocytes were found in small numbers. Blood vessels typically contained a moderate volume of blood.

After 48 hours of panthenol ointment application, histological features closely resembled those of the control group (fig. 1 F). In the papillary layer of the dermis, cellular elements were represented by fibroblasts, lymphocytes with plasmocytes frequently forming small clusters at the epidermal-dermal junction. Blood vessels showed predominantly moderate blood filling.

At 72 hours post-irradiation, animals in the control group exhibited mainly well-defined epidermal layers, although some areas appeared indistinct (fig. 1 G). The epidermis displayed variable thickness with focal basal cell hyperplasia. Well-formed papillae and pseudopapillae were commonly observed. The granular layer was clearly visualized and, in some regions, markedly thickened. A moderate number of intraepithelial lymphocytes was observed. Epithelial cells with hydropic degeneration were infrequent and predominantly focal. In the papillary layer of the dermis, there was a moderate number of cells with a predominance of fibroblasts. Blood vessels were with moderate plethora.

At this time point, under the influence of EMHPS gel, the boundaries between the epidermal layers were clearly defined, and the epidermal thickness was approximately preserved (fig. 1 H). In the papillary layer of the dermis, a moderate number of cellular elements was found, including fibroblasts, lymphocytes, plasma cells and a few focally located neutrophils. Blood vessels were mainly moderately engorged with blood.

After 72 hours of topical panthenol treatment, the epidermal layer boundaries in the irradiated skin were not uniformly well defined; some areas exhibited disrupted stratification (fig. 1 I). The stratum corneum was partially desquamated, focally thickened. In the papillary dermis, a moderate number of cells was found, including fibroblasts, lymphocytes and plasma cells (the latter with a small focal arrangement). Blood vessels were predominantly moderately engorged with blood.

Thus, UV irradiation induced significant histological alterations in the skin, while treatment with therapeutic agents partially mitigated these histopathological changes, warranting further quantitative evaluation via morphometric analysis.

Histomorphometric investigation

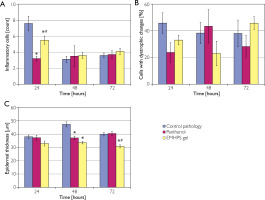

The inflammatory cell infiltrate in the control group reached its maximum density at 24 hours post-UV irradiation and demonstrated a significant spontaneous reduction by approximately 50% at both 48 hours (p < 0.001) and 72 hours (p < 0.001) (fig. 2 A). Administration of EMHPS gel during the acute phase post-irradiation resulted in a 1.4-fold reduction in inflammatory cell count compared to untreated controls (p < 0.001). In contrast, treatment with panthenol ointment elicited a more substantial anti-inflammatory effect, reducing inflammatory cell infiltration by 2.4-fold relative to controls (p < 0.001), which was statistically superior to the effect of EMHPS gel (p < 0.001). At subsequent time points, differences in inflammatory cell counts between treatment groups were no longer statistically significant.

Figure 2

The EMHPS gel action on morphometric parameters in the skin micropreparations after UV exposure: count of inflammatory cells (A), percentage of cells with dystrophic changes (B), and epidermal thickness (C). *p < 0.05 as compared to controls; #p < 0.05 as compared to panthenol ointment

The proportion of keratinocytes with dystrophic changes in the epidermis of animals of the control group ranged between 46–38% (fig. 2 B). The EMHPS gel caused a tendency to decrease this indicator by 1.4 times (p < 0.25) 24 hours after the UV exposure as compared to control. At this time point, topically applied panthenol exhibited a comparable effect, with a trend toward significance (p < 0.1). Forty-eight hours post-UV irradiation, treatment with EMHPS gel resulted in a 1.7-fold reduction in the number of keratinocytes exhibiting hydrophic degeneration compared to controls (p < 0.1). By 72 hours following UV exposure, differences between the experimental and reference groups were no longer statistically significant.

Epidermal thickness with UV exposure without pharmacological agents averaged 38 μm at 24 hours, increased to 47.3 μm at 48 hours, and decreased to 39.9 μm at 72 hours (fig. 2 C). The EMHPS gel caused a tendency to decrease the thickness of the epidermis in the early period of observation (p < 0.1) and significantly reduced it after 48 and 72 hours by 1.4 and 1.3 times (p < 0.001), respectively, compared to controls. Panthenol ointment acted similarly only 48 hours after irradiation.

Therefore, 5% EMHPS gel applied topically after a single UV exposure prevented thickening of the epidermis, infiltration of inflammatory cells and exhibited a trend toward a reduction in the prevalence of cells displaying dystrophic alterations.

Biochemical changes in the skin

24 hours after UV irradiation, the MDA content in the skin of control animals increased by 1.5 times (p < 0.001) as compared to intact rats (table 1). It stayed at this level 48 and 72 hours after the exposure to UV rays (p < 0.001). 24 hours after UV exposure, the SOD activity in the skin of control rats decreased by 1.3 times (p < 0.01) as compared to intact animals, but catalase activity did not change. 48 hours after, in this group, the SOD activity was decreased to the same degree (p < 0.05) that was accompanied by 1.4-fold elevation (p < 0.01) of the catalase activity as compared to intact rats. After 72 hours, in the control group, a decrease in the SOD activity by 1.5 times (p < 0.001) was recorded. In this period, the catalase activity decreased by 1.6 times (p < 0.01) in comparison with controls.

Table 1

The effect of EMHPS gel on the content of malondialdehyde and the activity of antioxidant enzymes in the skin after the UV irradiation (M ± SEM)

| Period | Groups of animals | MDA [µmol/g] | SOD [activity units] | Catalase [µcat/g] | Hydroxy-proline [µmol/g] | GAG [µmol/l] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact | 5.08 ±0.44 | 8.65 ±0.23 | 0.264 ±0.004 | 0.662 ±0.021 | 1.067 ±0.017 | |

| After 24 hours | Control | 7.42 ±0.34* | 6.88 ±0.30* | 0.307 ±0.049 | 0.934 ±0.059* | 1.403 ±0.039* |

| Panthenol ointment | 7.53 ±0.33* | 7.83 ±0.44 | 0.346 ±0.034 | 0.857 ±0.060* | 1.389 ±0.044* | |

| EMHPS gel | 6.26 ±0.34*#^ | 8.47 ±0.34# | 0.291 ±0.046 | 0.904 ±0.090* | 1.332 ±0.066* | |

| After 48 hours | Control | 7.72 ±0.34* | 6.72 ±0.35* | 0.381 ±0.016* | 0.855 ±0.134* | 1.740 ±0.049* |

| Panthenol ointment | 7.34 ±0.36* | 8.25 ±0.60 | 0.307 ±0.031 | 0.506 ±0.108# | 1.370 ±0.071* | |

| EMHPS gel | 6.69 ±0.19*# | 8.36 ±0.33# | 0.234 ±0.024# | 0.506 ±0.069# | 1.314 ±0.067*# | |

| After 72 hours | Control | 7.60 ±0.59* | 5.77 ±0.34* | 0.163 ±0.011* | 1.296 ±0.058* | 1.852 ±0.018* |

| Panthenol ointment | 6.94 ±0.17* | 7.11 ±0.38 | 0.211 ±0.022 | 0.669 ±0.050# | 1.674 ±0.102* | |

| EMHPS gel | 6.77 ±0.22*# | 8.53 ±0.55# | 0.244 ±0.028# | 0.608 ±0.084# | 1.584 ±0.042*# |

After 24 hours, the EMHPS gel inhibited the accumulation of MDA in the skin. At this moment of observation, it decreased the MDA level by 1.2 times (p < 0.05) as compared to controls. 48 hours after UV irradiation, topical EMHPS reduced the MDA concentration to the same degree (p < 0.05). Similar changes of this lipid peroxidation biomarker took place 72 hours after UV exposure (p < 0.02). In all the periods, the EMHPS gel restored the SOD activity in the skin of the test area. It increased this parameter by 1.2 times 24–48 hours (p < 0.02 and p < 0.05, respectively) and by 1.5 times (p < 0.002) 72 hours as compared to controls. The investigated gel did not affect the catalase activity 24 hours after UV exposure and normalized it at two other moments of observation (p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively). Panthenol, a reference preparation, did not influence the MDA level and antioxidant enzyme activity as compared to controls during the entire experiment.

The results of the determination of hydroxyproline and GAG in the skin of the test area are shown in table 1. The content of free hydroxyproline in the dorsal skin of control rats was increased during the entire period of observation. After 24 hours, the growth of this indicator was 1.4 times (p < 0.01), after 48 hours – 1.3 times (p < 0.05), and after 72 hours – 2 times (p < 0.001) as compared to intact rats. Daily treatment of UV irradiated skin with the EMHPS gel reduced the hydroxyproline concentration by 1.7 times (p < 0.001) after 48 hours and by 2.1 times (p < 0.001) after 72 hours as compared to controls. The reference preparation also decreased the hydroxyproline level at two last moments of observation (p < 0.001), which was similar to the EMHPS effect.

24 hours after UV irradiation, in the control group, the GAG concentration in the skin of the test area increased by 1.3 times (p < 0.001) compared to intact rats. It remained elevated by 1.6 times (p < 0.001) after 48 hours and by 1.7 times (p < 0.001) after 72 hours. The new gel decreased the content of the total GAG fraction in the skin by 1.3 times (p < 0.05) after 48 hours and by 1.2 times (p < 0.05) after 72 hours against controls. Contrary to the studied gel, panthenol did not change the GAG concentration at any moment after the UV exposure.

Therefore, the EMHPS gel was able to inhibit the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products, diminished changes in the SOD and catalase activity as well as decreased the concentration of free hydroxyproline and total GAG fraction that was more active against the effect of the reference preparation.

DISCUSSION

Sunlight comprises both UVA and UVB radiation; therefore, in selecting an experimental model of acute UV-induced skin damage, we employed an erythema lamp designed for mini-solarium, which accurately simulates sunlight across both spectral ranges. A dose was slightly below the dose range for phototoxicity studies (for UVA) and fell within the dose range that caused mild erythema in rats (for UVB) [19]. When studying histological preparations of animals’ skin, characteristic histopathological changes (hydropic degeneration, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and increased epidermal thickness) were identified. Ultraviolet irradiation caused inflammation of the skin, which persisted for at least 72 hours with increased proliferative phenomena by the end of this period. This confirmed the data that acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and inflammation are observed at low doses of UVB even in the absence of erythema and edema [20].

Application of EMHPS gel resulted in a more uniform epidermal thickness, distinctly defined epidermal layers boundaries, and reduced presence of neutrophilic leukocytes and vascular congestion. The positive effect of the EMHPS gel on the structural elements of the skin exposed to UV radiation in morphometric analysis was characterized by a decrease in the count of inflammatory cells and a tendency towards a decrease in the percentage of keratinocytes with dystrophic changes after 24 hours (i.e. after a single application of the gel), as well as a significant decrease in the epidermal thickness after 48 and 72 hours (i.e. after 2–3 times application of EMHPS gel to the skin). This effect is comparable to the therapeutic impact of polyphenols, the heterocyclic antioxidants derived from plants, on the murine skin following UVB irradiation [21, 22]. Although there is ongoing debate among researchers concerning the role of antioxidants in the prevention and treatment of sunburn, ranging from skepticism about their efficacy to evidence supporting their substantial effectiveness, our findings align more closely with the latter perspective [23, 24].

We noted an increase in the MDA concentration in the skin of control animals starting from 24 hours after UV irradiation. This finding indicates an elevation of oxidative stress and consequent damage to macromolecules, particularly through lipid peroxidation, as previously described [25]. The observed decrease in the SOD activity may apparently be a result of this enzyme inhibition by the excessive concentration of the reaction product. The accompanying changes in catalase activity obviously reflected its role in the detoxification of hydrogen peroxide formed in the superoxide dismutase reaction and the dependence of such activity on the substrate concentration. Our results are consistent with those of other researchers, who have demonstrated that a single exposure to UVA radiation significantly reduces catalase activity, whereas UVB exposure leads to a decrease in SOD activity along with other alterations in antioxidant defense mechanisms [26]. This phenomenon is thought to be associated with the depletion of antioxidant reserves and an elevated level of lipid peroxidation products [27].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by UV irradiation in the skin are able to activate NF-κBdependent proinflammatory signaling pathways, which increase the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines [28]. Evidently, the consequence observed in our experiment is the initiation of inflammatory responses within the irradiated skin. The inflammation together with oxidative stress may explain an increase in the free hydroxyproline and GAG concentration in the skin of animals of the control group because one of the main effects of UV radiation on the skin is an increase in expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are responsible for the degradation of extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen and proteoglycans [29].

It was shown that EMHPS promoted up-regulation of antioxidant protection by increasing the SOD activity at all observation moments and by normalizing the catalase activity 48 and 72 hours after UV irradiation. Consequently, reduction in UVinduced lipid peroxidation, assessed as MDA, was observed. These results may be due to the EMHPS direct interaction with the lipophilic and hydrophilic radicals present in the cell membranes as well as its ability to increase the activity of SOD, catalase and glutathione peroxidase [10]. The EMHPS chelation of bivalent metal ions, especially iron ions, obviously plays a role in limiting of oxidative stress initiated in the skin of animals by UV exposure [10, 30].

It should be assumed that topical EMHPS interrupts the cascade of events induced by UV radiation, improves the natural antioxidant defense of the skin, prevents lipid peroxidation, and regulates signaling pathways that modulate inflammatory and dystrophy reactions. One apparent manifestation of this effect is the reduction in hydroxyproline and GAG concentrations in the treated skin area, suggesting a mitigation of dermal extracellular matrix degradation through ROS scavenging and modulation of the MAPK/MMP/collagen signaling pathway, as similarly observed in skin cell cultures exposed to antioxidant agents [31].

The abovementioned processes occurring in the animals’ skin under the influence of EMHPS naturally caused morphological changes in the form of reduced infiltration by inflammatory cells and prevention of epidermal thickening. They confirmed a reduction in inflammation and proliferation in the skin, i.e. the therapeutic effect of EMHPS gel under the damaging effect of UV radiation. In this experiment, the effect of topical EMHPS was more consistent than the effect of panthenol, a reference preparation. Only in 1 case, when it came to the count of inflammatory cells in the skin, EMHPS was inferior to panthenol in the severity of changes. This suggests that the pronounced antioxidant activity of EMHPS confers significant therapeutic benefits in mitigating skin reactions induced by UV irradiation.

CONCLUSIONS

Excessive skin exposure to solar radiation or UV light can result in sunburn, which in certain cases necessitates topical pharmacological intervention. The experiments show that the use of the synthetic antioxidant EMHPS in the form of a gel in animals with UV skin damage has a therapeutic effect, limiting oxidative stress, normalizing the state of the extracellular matrix in the skin, reducing the inflammatory response and epidermal thickening. In the majority of tests, the effect of the antioxidant gel was not inferior to the effect of panthenol ointment, a standard medicine recommended for the sunburn treatment. The data obtained show the prospects for further studies of EMHPS for photoprotection, since the preventive effect as well as the treatment of adverse effects of chronic UV exposure, such as photoaging or cancerogenesis, seem to be even more important than the local therapeutic effect in the acute skin reaction to UV irradiation.