Introduction

In the general population the prevalence of Hymenoptera sting ranges from 56.6% to 94.5% and varies on different continents. Insect (Vespula germanica, Vespula vulgaris, Vespa crabro, Apis mellifera, Bombus) stings may lead to a range of reactions from mild and local symptoms to a life-threatening anaphylaxis [1]. Most reactions such as transient pain, itching and swelling after a sting are normal responses. A large, local reaction (LLR) lasts longer than 24 h and the swelling exceeds a diameter of 10 cm [2]. Systemic sting reactions can be as follows: serious hypersensitivity events with symptoms from cutaneous, gastrointestinal, respiratory and cardiovascular systems. The generalized, allergic reaction to Hymenoptera stings affects 0.3% to 3.5% of adults and the mortality due to the insect sting ranges from 0.03% to 8.9% fatalities per 1 000 000 of the general population per year [3, 4].

Venom immunotherapy (VIT) can protect against severe anaphylactic reactions (SR) at re-sting 80–100% of allergic to Hymenoptera venom subjects [5, 6]. Several studies have shown that VIT improves the quality of life of patients with a history of systemic reactions after Hymenoptera stings [7–9]. The VIT protocols of the initial phase are as follows: ultra-rush (3.5 h), rush (2–3 days), modified rush (6–8 weeks) and slow (16–20 weeks). The main goal of the protocols is to reach the maintenance dose of 100 µg of the venom extract. After the initial treatment, the venoms are administered at scheduled intervals of 4 to 12 weeks [10, 11].

Rush protocols have been used since the 1980s and the side effects of the therapy are comparable with the conventional method. However, the honeybee venom administration in the build-up phase of VIT has been associated with a higher incidence of systemic reactions, which is five-fold more frequent than for wasp venom [12]. Rush VIT provides the advantage of early protection from systemic anaphylaxis after Hymenoptera re-stings [13–15]. The protocol is preferred in our hospitalized patients.

However, the mechanisms of induction of immunological tolerance produced by VIT are still little known. It has been shown that VIT modulates Treg and Breg cell activity. Recent reports have pointed to the role of dendritic cells and their modification of an allergic Th2-type of response to a Th1-type one. The changes in T-cell reactivity observed during VIT lead to increased production of IL-10 and TGF-β, and decreased secretion of IL-13 and IL-4. It has also been reported that the augmented level of inducible Treg cells stimulates naïve B cells to class-switching towards IgG4 that competes with IgE for allergen-binding receptors on mast cells and basophils [16, 17]. Finally, the specific immunotherapy contributes activity of effector cells such as basophils, mast cells and eosinophils. Previously, most reports discussed the final immunological effects of VIT after a long-term course of therapy [18, 19]. It was proven that eosinophils play an important role in IgE-mediated allergic reactions [20].

It is well documented that the cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and chemokines such as eotaxins are involved in eosinophils’ activation and migration. Apart from these factors, we also assessed the impact of venom immunotherapy on other cytokines that influence eosinophils such as IL-17E/IL-25 and the chemokine CCL5/RANTES.

Aim

In this respect, the present study was conducted to analyze the blood eosinophil count, CCL5/RANTES and IL-17E/IL-25 concentrations before and after the initial phases of the rush protocol of VIT. The additional goal of this study was to investigate the immunological differences between bee and wasp venom immunotherapy.

Material and methods

Participants

Forty individuals (14 males, 26 females) of mean age 41.03 ±12.43 years were included in the study. The patients were admitted to the Department of Allergology, Clinical Immunology and Internal Diseases between January 2011 and December 2015. All participants completed a medical examination with an allergist.

The diagnosis of a Hymenoptera venom allergic reaction was confirmed by a clinical history, positive specific IgE (sIgE) and intradermal tests. The patients had a history of severe grade 3 or 4 allergic reactions, according to the Mueller’s classification [21]. None of the subjects had received an allergen immunotherapy for Hymenoptera venom. The laboratory tests also excluded toxic reaction to the venoms during VIT. Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients qualified for VIT

Wasp venom sensitized patients

Twenty patients (4 men, 16 women; mean age: 41.17 ±9.52 years, range: 18–71 years) who had experienced systemic reactions to wasp stings were included in the study. The average time between the last sting and the hospitalization was 20.45 ±27.16 months.

Bee venom sensitized patients

Twenty patients (9 men, 11 women; mean age: 40.9±15.35 years, range: 16–68 years) who had experienced systemic reactions to honey bee, but no honey bee stings, were included in the study. The average time between the last sting and the hospitalization was 15.39 ±13.53 months.

Skin tests

The intradermal tests were performed with venom concentrations in the range of 0.001 to 1.0 µg/ml to find the minimum concentration giving a positive result. Positive test results were accepted at 5 mm diameter of wheal [22]. Positive (1% histamine hydrochloride) and negative (sodium-chloride 0.9%) control tests were performed. The diluent (HSA-saline) was negative and histamine was a positive control. The tests were performed after a minimum of 6 weeks after the last sting.

Number of peripheral blood eosinophils

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes the day before and the day after the initial phase of VIT was performed. An automated analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL) was used to determine the eosinophil counts.

Serum samples

The blood for the examination was collected from the ulnar vein into the test tube using the closed Vacutainer system. Basic morphological blood parameters were additionally determined in all patients.

Measurement of allergen-specific and total IgE

The blood from patients sensitized to Hymenoptera venom was analyzed a minimum of 6 weeks after the last sting. The serum concentrations of total IgE and specific IgE were measured using the fluoro-immuno-enzymatic method (FEIA) on the UNICAP100 apparatus using the kits of Phadia AB according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The levels of specific IgE less than 0.35 kU/l were considered negative.

Cytokine analysis

The concentrations of serum interleukin IL-17E/IL-25 and RANTES were determined by the ELISA enzymatic method using a kit from Abnova and for RANTES the kit from eBioscence was used. The tests were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The readout and calculation of the concentrations were performed using the apparatus and the software of BIO-TECH INSTRUMENTS INC ELX 800. All determinations were performed the day before and the next day after VIT was performed.

Baseline serum tryptase

Tryptase levels were determined by means of Immuno CAP. Patients with the serum level of the enzyme > 11.4 ng/ml were excluded [23].

VIT protocol

The rush VIT protocol was used in this study [24]. During the therapy, the patients were monitored for blood pressure, pulse, electrocardiography, and peak flow in the intensive care unit. Ten incremental doses of venom were administered subcutaneously every 30 min. The initial dose was 0.01 µg of venom, and the subsequent doses were increased until a cumulative dose of 68.5 µg was administered on day 1. The maximum dose (100 µg) was reached on day 2, and the cumulative induction dose was approximately 180 µg of venom. The venom immunotherapy was performed with Venomenhal (Allergen extracts – Hymenoptera venom allergens, Hal Allergy).

Ethics

This study was approved by the Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz Research Ethics Committee, and each participant provided written informed consent prior to the study enrolment.

Statistical analysis

The results were then analyzed statistically using SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons of quantitative and qualitative data were checked with the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 40 patients were included in the VIT according to the EAACI guidelines [23]. All subjects had a history of systemic anaphylaxis (Table 1) and positive skin tests with bee or wasp venom; specific IgEs for the venoms were recognized as positive at the concentration of > 0.36 U/l.

We measured the number of blood eosinophils, concentrations of CCL5/RANTES and IL-17E/IL-25 before and after the patients underwent the subcutaneous venom immunotherapy.

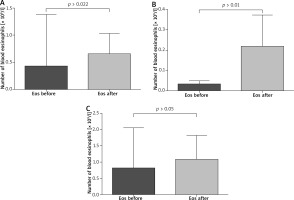

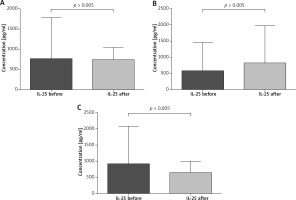

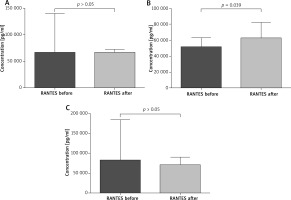

The paired sample t-test revealed that all patients after VIT had significantly higher eosinophil levels compared to the baseline (mean: 0.42 vs. 0.64, p < 0.05) (Figure 1). Moreover, in subjects treated with bee venom, CCL5/RANTES levels rose significantly (51 × 103 vs. 62 × 103, p < 0.05) while 17E/IL-25 dropped although not significantly (916 vs. 650, p = 0.069). The patients treated with wasp VIT did not show significant changes in those 2 markers (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 1

Effects of rush VIT on the number of peripheral blood eosinophils. A – All patients treated with bee and wasp venom. Eosinophils (Eos) before and 1 day after the initial phase of VIT. B – Patients treated with wasp venom. Eosinophils (Eos) before and 1 day after the initial phase of VIT. C – Patients treated with bee venom. Eosinophils (Eos) before and 1 day after the initial phase of VIT

Figure 2

Effect of the initial phase of Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy on serum IL-17E/IL-25 concentration. A – All patients treated with bee and wasp venom. 17E/IL-25 concentration before and 1 day after VIT. B – Patients treated with wasp venom. 17E/IL-25 concentration before and 1 day after VIT. C – Patients treated with bee venom. 17E/IL-25 concentration before and 1 day after VIT

Figure 3

Effect of initial phase of Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy on serum RANTES concentration. A – All patients treated with bee and wasp venom. CCL5/RANTES concentration before and 1 day after VIT. B – Patients treated with bee venom. CCL5/RANTES concentration before and 1 day after VIT. C – Patients treated with wasp venom. CCL5/RANTES concentration before and 1 day after VIT

Discussion

The results presented in this paper show some immunological changes after the initial phase of venom immunotherapy. A number of studies have documented an initial increase of specific IgE levels to Vespidae venom. More recently Subramaniam et al. [25] documented the induction of CD1a-reactive T cells producing IFN-γ and IL-γ 13 during the first days of immunotherapy. Increased IL-13 production plays an important role in switching IgE class gene expression. Here we have shown that VIT is associated with induction of eosinophils, particularly in the group of wasp venom treatment patients. Cytokines such as IL-5, IL-3, GM-CSF have been recognized as inducers for eosinophils’ development and differentiation factors [26]. The most specific is IL-5. The cytokine stimulates pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells’ differentiation into eosinophils, and release of these cells into the circulation [27]. In considering the increase of eosinophils in the circulation observed in our study among the motioned cytokines, we have paid attention to the chemokine RANTES (Regulated upon Activation, Normally T Expressed, and presumably secreted), also termed CCL5 [28]. RANTES has been demonstrated as a potent chemotactic factor for dendritic cells (DCs), T cells, eosinophils, macrophages, monocytes, natural killer (NK) cells and leukocytes. The endothelial and epithelial cells, fibroblasts, activated T lymphocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils can produce RANTES. The chemokine also possesses various functions other than chemotaxis, such as mediating IL-2 secretion by T cells and IL-12 secretion by macrophages, and acts as an antiapoptotic factor for macrophages [29]. It has been shown that RANTES stimulates maturation of DCs. Dendritic cells play a crucial role in tolerance induction by production of Tregs and secretion of cytokines [30, 31]. In considering the increase of eosinophils in the circulation during the initial phase of VIT we assume that CCL5/RANTES and DCs’ cytokines may result in the eosinophil response. It has been reported by Gawlik et al. [32] that the chemokine level was significantly reduced after 6 days of rush venom immunotherapy. Our observations have shown that in patients treated with bee venom the CCL5/RANTES concentration increased after venom administration (p = 0.39). However, the level of CCL5/RANTES in the wasp group and in the combined group of wasps and bees did not change significantly. Our results could suggest that RANTES is involved in immunological responsiveness during venom immunotherapy.

Recently, the family of IL-17 has been extensively studied. This interleukin family consists of IL-17, IL-17B, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17E (also called IL-25) and IL-17F. IL-17E/IL-25 is produced by mast cells, Th2 cells, eosinophils, basophils, alveolar macrophages, microglia, epithelial and endothelial cells [33, 34]. There are many studies indicating that IL-17E/IL-25 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of allergic diseases [35, 36]. Our data have indicated different levels of IL-17E/IL-25 in patients treated with bee and wasp venom. Interestingly, in the wasp group we observed a higher concentration of IL-17E/IL-25 and in the case of the bee group a lower concentration of this cytokine. Differences in the wasp and bee groups might be due to different venom composition and allergenicity [37, 38]. The major allergens of honeybee (Apis mellifera) are phospholipase A2 (Api m 1), hyaluronidase, (Api m 2) and melittin (Api m 4). Wasp venom (Vespula germanica, Vespula vulgaris) contains prominent allergens such as phospholipase A1 (Ves v 1), hyaluronidase (Ves v 2.0101), hyaluronidase (Ves v 2.0201) and antigen 5 (Ves v 5) [39–41]. Recently, studies on phospholipase A2 have shown that the enzyme induced Treg and showed strong capability of immunosuppressive effects [42]. Accordingly, we have hypothesized that Api m 2 and other components of bee venom can contribute to the differences in IL-17E/IL-25 activity observed in our study [43–45].

We have reported here some immunological changes during the first phase of venom immunotherapy. Our analysis shows the eosinophils’ response and the possibility of CCL5/RANTES and IL-17E/IL-25 participation in this immunological modulation.

We have undertaken to continue studies to explain extensively the influence of VIT on eosinophils and their modulators.

Conclusions

We believe that in the early phase of venom immunotherapy above and beyond the specific IgE antibody induction, the immunological cells such as eosinophils, cytokines such as RANTES and IL-17E/IL-25 can contribute to the immunological response. The present studies show that the initial VIT raises the number of peripheral eosinophils, and increases the production of CCL5/RANTES in bee-treated patients. The expression of IL-17E/IL-25 was slightly reduced in the bee patient group and was not significantly increased in the wasp group during the therapy. Based on these results, and other elegant reports, we suggest that the immunological response during VIT might occur in two stages. The first stage is the immunological mobilization and the second one is the decrease of allergic responsiveness to Hymenoptera venom.