Introduction

The EAACI Guidelines define anaphylaxis as “a severe, life-threatening generalized or systemic hypersensitivity reaction” [1]. It represents the most extreme clinical presentation of an allergic reaction, often triggered by factors such as food, insect venom, medications or immunotherapy, with food being the most common cause in children under 2 years old. Recent studies indicate that cow’s milk and hen’s egg proteins are frequently responsible for anaphylaxis in young children, followed by wheat, cashew nuts, hazelnuts, and peanuts [2]. However, allergen frequency varies across countries due to cultural differences in food preparation and consumption practices. Over recent decades, an increase in allergies and anaphylaxis cases has been observed [2]; however, it is evident that many cases go unreported and untreated.

Epinephrine is currently considered the most effective first-aid treatment for anaphylaxis, yet few children receive it [3]. Alarmingly, not only do many children fail to receive epinephrine during their first anaphylactic episode, but patients often do not receive a prescription for future use. Even when prescribed, epinephrine is rarely administered by patients or their guardians [3]. This trend is particularly concerning as anaphylaxis can be severe in certain cases, especially in patients with a history of asthma, rapid symptom onset, or who present with signs such as poor general appearance, tachycardia, or hypotension upon arrival at the Emergency Department [4]. Accurate diagnosis of anaphylaxis in infants can be challenging for physicians due to differences in clinical presentation, coexisting conditions, and the difficulty of assessing subjective symptoms in very young children [5].

Anaphylaxis is a recognized cause of death across all age groups, though the fatality rate is less than 1 per million in most developed countries [6]. This statistic, however, is likely underestimated due to underreporting and underdiagnosis. Additionally, data from middle- and low-income countries are limited. This discrepancy may be partly due to misclassification of anaphylaxis within the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD), though the future implementation of ICD-11 – featuring a pioneering chapter dedicated to allergic and hypersensitivity reactions – may improve reporting accuracy [7]. Currently, there is a lack of consensus on the definition of anaphylaxis among healthcare providers. Studies have shown that practitioners often assess anaphylaxis cases differently, leading to instances where one clinician may classify a case as anaphylaxis, while another may not [6, 8, 9].

A rise in hospital admissions due to anaphylaxis has been reported in Western countries, including Australia and the United States [10]. The most substantial increase has been noted among children under 1 year of age, with a concurrent rise in the severity of allergic reactions [10]. Similar trends have been observed in countries such as South Korea [11], Canada [12], and Poland [13, 14]. Conversely, a decrease in anaphylaxis cases has been reported in some Asian countries, such as Thailand, in recent years [15]. Emerging research also points to a rising prevalence of anaphylaxis in European countries like Finland, Sweden, Spain, and the United Kingdom [16], as well as in Hong Kong [17].

Aim

The primary aim of our study was to gather data on patients aged 0–2 years who experienced food-induced anaphylaxis, analysing the causative agents, clinical manifestations, age at reaction onset, treatment approaches, and disease regression to build a comprehensive profile of these cases. We also sought to assess the frequency of various treatment methods, including epinephrine administration, and to present our recommendations for healthcare providers to improve future anaphylaxis management. It is important to note the limited number of scientific studies focusing on anaphylaxis in the youngest age group.

Material and methods

Data collection

The Department where study was conducted admits approximately 1,400 inpatients each year. For this study, we used cases admitted to inpatient care between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2023. Diagnoses were recorded by attending physicians in the hospital’s system. We retrospectively reviewed diagnoses under “anaphylaxis", “anaphylactic shock", “food allergy”, “shock”, and “allergic reaction”, identifying 87 patients. Additional data, including elicitors, clinical manifestations, age of reaction, treatment, disease severity, and regression, were extracted from the databases of our department, as well as the Emergency Department. Ethics committee approval was obtained for this study (122.6120.250.2015).

Diagnostic criteria

We employed the WAO diagnostic criteria for anaphylaxis, updated in 2024 [18]. The study included only infants and children aged 0 to 2 years. After the retrospective review, 87 qualifying patient cases were included based on the detailed medical history and subsequent diagnostics confirming the diagnosis of food allergy. In all children included in the study (87) the further diagnostic process was meticulously analysed. In all these 87 patients in a period of 4–16 weeks after the anaphylactic episode, diagnostics confirming the diagnosis of food allergy was performed, based on measurement of allergen-specific IgE to the suspected allergen or skin prick tests (in case of lack of contraindications to conducting such tests and/or lack of possibility of measuring specific IgE). The ImmunoCAP® Specific IgE test (Pharmacia Diagnostics) was used for specific IgE antibodies detection. Results of sIgE > 0.35 kU/l were considered as positive. We evaluated patient gender, age, pre-existing conditions, allergies, reaction elicitors, reaction time, and symptoms. Additionally, we analysed the treatment patients received both from guardians and medical professionals. The severity of anaphylaxis was graded using the five-grade Sampson classification for food-induced anaphylaxis, which also indicates severity levels requiring epinephrine administration [19]. We used Sampson’s severity score because it is routinely used in our Allergy Centre for evaluation of children with food-induced anaphylaxis. This severity grading system was originally developed for food allergic reactions and with its use it is possible to grade the reaction also if only single symptoms, such as hypotension, are registered.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc software (Jagiellonian University, version 22.021). Descriptive statistics were presented as counts and percentages for qualitative data and as means and medians for quantitative data. Multiple regression analysis was used to explore associations between symptom severity, comorbidities, and clinical history. Comparisons of quantitative variables were made using Fisher’s exact test, with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

General information

The 87 cases covered in this study represented approximately 1% of all patients admitted annually to our department. Population characteristics, including gender, age, time from consumption to symptom onset, concomitant diseases and family history of atopy are presented in Table 1. Reactions occurred after the first exposure to the allergen in 68 (78.2%) children, whereas 19 (21.8%) children had previously been diagnosed with sensitization to the trigger and were therefore on elimination diets.

Table 1

Characteristics of the examined group of patients

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 87 |

| Age [months] mean ± SD; age range | 13.3 ±5.7; 4–24 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 54 (62) |

| Female | 33 (38) |

| Reaction causing allergen, n (%) | |

| Cow’s milk protein | 42 (48.3) |

| Hen’s egg protein | 27 (31) |

| Peanuts and tree nuts (walnut, cashew, hazelnut) | 10 (11.5) |

| Peanuts | 2 (2.3) |

| Walnuts | 4 (4.6) |

| Cashew nuts | 3 (3.4) |

| Hazelnuts | 1 (1.1) |

| Other (wheat, sesame, kiwi, linseed) | 8 (9.2) |

| Wheat | 4 (4.6) |

| Sesame | 2 (2.3) |

| Kiwi | 1 (1.1) |

| Linseed | 1 (1.1) |

| Time from food consumption to reaction occurrence [min] | 16.9 ±1.3; 1–120 |

| Accompanying atopic diseases, n (%) | |

| Atopic dermatitis | |

| Early childhood asthma* | |

| Multi-food allergy** | |

| Family history of atopy*** |

* Early childhood asthma was diagnosed based on the Asthma Predictive Index developed by Castro-Rodriguez [56].

Triggers

The most common trigger of anaphylaxis in our study was cow’s milk protein, followed by hen’s egg protein. Further elicitors included tree nuts and peanuts (10 patients). Other triggers (8 patients) were wheat, sesame, kiwi and linseed. The prevalence of each trigger is shown in Table 1. Among children after anaphylaxis to hen’s egg protein or cow’s milk protein, double sensitization to both these allergens was observed in 13 (18.6 %) children. Median specific IgE serum levels for hen’s egg and cow’s milk are presented in Table 2. Based on the medical documentation prior to the anaphylactic episode and diagnostic tests after anaphylaxis, cow’s milk protein (CMP) sensitization was assessed in 49 children (7 had no anaphylaxis to CMP, but had positive sIgE found prior to anaphylaxis episodes to other food than milk) and hen’s egg protein (HEP)sensitization – in 33 children (6 had no anaphylaxis to HEP, but had positive sIgE found prior to anaphylaxis episodes to other food than egg).

Table 2

Values of specific IgE for cow’s milk and hen’s egg protein (kU/l)

| Parameter | sIgE CMP | sIgE HEP |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size* | 34 | 25 |

| Lowest value [kU/l] | 0.020 | 0.040 |

| Highest value [kU/l] | 100.000 | 100.000 |

| Arithmetic mean | 25.898 | 23.824 |

| 95% CI for the arithmetic mean | 13.265 to 38.531 | 11.587 to 36.062 |

| Median | 5.025 | 12.300 |

| 95% CI for the median | 2.182 to 23.262 | 3.834 to 29.966 |

| Variance | 1310.900 | 878.928 |

| Standard deviation | 36.206 | 29.646 |

Symptoms

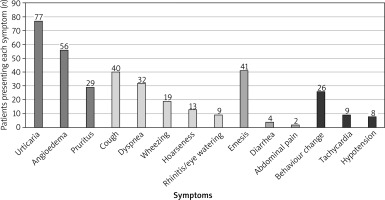

In this study, the most common cutaneous and mucocutaneous reactions were urticaria, angioedema, and pruritus. Respiratory symptoms included dyspnoea, cough, wheezing, hoarseness, rhinitis, and eye watering. Cardiovascular and neurological symptoms included tachycardia, hypotension, and behavioural changes, while gastrointestinal symptoms included emesis, abdominal pain (obtained based on sudden, intense crying and parents’ observation of pulling legs up toward the belly) and diarrhoea.

The majority of the examined population – 81 (93.1%) patients exhibited cutaneous and mucocutaneous symptoms. Respiratory symptoms were observed in 54 (62.1%) cases, gastrointestinal symptoms in 43 (49.4%) cases, and cardiovascular/neurological symptoms in 32 (36.8%) cases. In 8 (9.2%) cases, blood pressure was not measured during transport or upon arrival at the Emergency Department and our Allergic Centre. Symptom distribution across different systems with numbers of patients presenting each symptom is detailed in Figure 1. In cases where hypotension was recorded, the blood pressure was taken on admission to our Department. The mean systolic blood pressure in these cases was 69 mm Hg (±2 SD, median 68, range: 67–72 mm Hg).

Disease progression and treatment

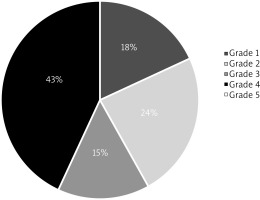

Anaphylaxis severity was graded according to Sampson’s classification for food-induced anaphylaxis [19]. Most patients were classified as having grade 4 anaphylaxis, with the percentage grade distribution shown in Figure 2. It is worth mentioning that grade 5 being the most severe one was not recorded in our patients’ population. Based on the Sampson’s classification, grade 4 anaphylaxis can already be categorized as anaphylactic shock, which signifies that anaphylactic shock was diagnosed in 38 (43%) children of our study population.

Moreover, asthma and hen’s egg protein allergy were identified as risk factors for more severe reactions as presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Influence of various factors on the severity of anaphylaxis based on multiple regression analysis (Sample size: 87)

Initial treatment was provided by guardians in 53 (60.9%) cases and was based on first (dimetindene) or second (cetirizine) generation of antihistamines. During transportation and in the Emergency Department, the medical team administered medications, including fluid support, to 75 (86.2%) patients. In 4 (4.6%) cases, symptoms resolved spontaneously without medical intervention.

Treatments administered included H1 antagonists, glucocorticosteroids, bronchodilators, epinephrine, and fluid support. Medication types and their correlation with anaphylaxis severity are shown in Table 4. H1 antagonists were the most frequently administered drug, mainly by guardians, while glucocorticosteroids were commonly used by the emergency medical team.

Table 4

Medication types and their correlation with anaphylaxis severity

| Treatment | Total (n = 87) | Mild/moderate anaphylaxis* (n = 49) | Severe anaphylaxis** (n = 38) | P-value# |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epinephrine, n (%) | 8 (9) | 4 (8) | 4 (11) | 0.706 |

| Corticosteroid, n (%) | 69 (79) | 34 (69) | 35 (92) | 0.014 |

| Anti-H1, n (%) | 70 (80) | 40 (82) | 30 (79) | 0.790 |

| Salbutamol nebulisation, n (%) | 6 (7) | 1 (2) | 5 (13) | 0.08 |

| Fluids, n (%) | 18 (21) | 9 (18) | 9 (24) | 0.791 |

Discussion

Food is the leading known trigger of anaphylaxis in children presenting to emergency departments in Europe and the United States, though the prevalence varies by local culture and dietary habits [20]. Our study provided insight into food-induced anaphylaxis in infants, highlighting the current prevalence of this condition in the youngest population. We specifically focused on young children rather than adolescents as older children show a distinct clinical presentation due to additional factors such as insect venom or medications.

As observed in other paediatric studies, our research found a predominance of male patients [21–26], with 54 (over 62%) cases occurring in boys, who also showed a higher likelihood of hospitalization after anaphylactic shock [27]. The study indicates that male infants often exhibit a stronger Th2 immune response, which predisposes them to allergic sensitization.

In contrast, females generally develop a more balanced Th1/Th2 immune response over time, which may account for the observed sex differences in allergy prevalence [28].

Additionally, studies have shown that boys tend to have higher total and allergen-specific IgE levels compared to girls. This elevation in IgE is associated with more frequent and severe allergic reactions in male children [29].

It is common knowledge that a positive family history of atopy is a risk factor for atopic disease in offspring [30, 31]. Nevertheless, it is not efficient for early screening for food allergy in offspring. However, a combination of a positive parental atopic history and occurrence of atopic dermatitis in offspring could be a reason for such early screening [32] as atopic dermatitis was the most prevalent concomitant disease in our study population.

In line with findings from other studies, cow’s milk protein was the most frequent cause of anaphylactic reactions in our cohort, followed by hen’s egg (HE) protein [2, 11]. While peanuts or other tree nuts are common triggers in other populations [13, 33], Ko et al. identified a correlation between age and common anaphylaxis triggers, with HE protein being most prevalent in infants and peanuts being more common in toddlers and preschoolers [22]. This discrepancy reflects regional dietary patterns; in Poland, infants are less likely to consume peanut-based products than in some Western countries, which correlates with a lower frequency of peanut-induced anaphylaxis among children under two. Current guidelines, however, recommend introducing peanuts into infants’ diets before 6 months to reduce the risk of peanut allergies [34, 35].

The mean concentration of specific IgE for cow’s milk was more than twice as low as for hen’s egg protein. The occurrence of an anaphylactic reaction after consuming cow’s milk protein allergen, even at low specific IgE levels, can be explained by the degree of milk allergen processing. Reactions in our children were most commonly observed after the consumption of modified milk formula, yogurt, or cottage cheese. In the case of hen’s egg protein, the reactions were triggered by hard-boiled eggs or scrambled eggs. It is known that heating of food changes protein conformation and lowers allergenicity [36].

Our study found that cutaneous and respiratory symptoms occurred more frequently than gastrointestinal and cardiovascular symptoms, aligning with other research findings [14, 23, 34]. Gawryjołek and Krogulska found cutaneous, respiratory and oropharyngeal symptoms to be common in the examined population of children aged 0–3 years [37]. Kahveci et al., however, reported higher rates of skin, neurologic, and nausea-vomiting symptoms in infants compared to toddlers and preschoolers [38]. In our cohort, gastrointestinal symptoms like emesis and diarrhoea were common, though abdominal pain was rarely noted, likely due to infants’ limited ability to verbalize pain. This underreporting could hinder accurate assessment and diagnosis. Pistiner et al. highlighted the similarities and differences in anaphylaxis presentation in infants and toddlers, suggesting that modifying the current diagnostic terminology might improve recognition in nonverbal populations [39]. Similarly, Handorf et al. developed modified criteria tailored to infants and young children, enhancing anaphylaxis identification in these age groups [40]. The onset of symptoms in our study varied from 1 to 120 min post-exposure, with an average onset time of 17 min, underscoring the importance of close monitoring after introducing new dietary items.

Severity assessment in our study was based on H.A. Sampson’s grading system for food-induced anaphylaxis [19], with most cases presenting at grade IV, indicating life-threatening symptoms. We observed a correlation between HE protein allergy or asthma and more severe anaphylactic responses, corroborating findings from Cichocka-Jarosz et al., who also found these factors associated with reaction severity [14]. Prosty et al. noted that only 39.4% of patients with egg-induced anaphylaxis had a prior diagnosis of egg allergy, suggesting the need for vigilance in cases of suspected egg-induced anaphylaxis, particularly in younger children who may lack a formal allergy diagnosis [41]. While asthma may increase the risk of severe anaphylaxis, this requires further investigation as some studies have not confirmed this correlation [42]. In our study, over 90% of patients had blood pressure monitored either during transportation or upon arrival at the Emergency Department or on admission to the Allergy Centre. As majority of patients had blood pressure measured in our Department, hypotension was recorded in less than 10% of children. Blood pressure and heart rate should both be monitored as tachycardia can also indicate shock [43].

Glucocorticosteroids were the most frequently administered treatment in our study by the emergency medical team, though epinephrine – considered the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis [44] – was administered to only 4 patients with grade IV reactions. Spontaneous resolution of anaphylaxis in infants and small children is a possible phenomenon, though not fully understood. It likely involves a combination of physiological, immune, and compensatory mechanisms [45, 46]. Infants often have a more adaptable cardiovascular system. Their small size and high heart rate might allow them to maintain circulation better in some cases, preventing full cardiovascular collapse [47]. Moreover, infants have more reactive vagal responses, which can sometimes lead to transient low blood pressure or bradycardia, but also allow rapid recovery [48]. However, spontaneous resolution is unpredictable and should never be relied upon as a delay in epinephrine administration. The underuse of epinephrine aligns with findings from other studies, highlighting its underutilization, under-prescription, and suboptimal dosing [2, 9, 22, 23, 49]. This is in accordance with the results of other studies, where authors also found epinephrine to be underused in anaphylaxis management in infants and toddlers. The mean percentage epinephrine administration in European countries was 6.9% [10, 11, 32, 49]. A much greater level of awareness was reported in a study from Japan, where epinephrine use was very high at 69.1%. According to the World Allergy Organization, epinephrine is currently underused, and patients with a pre-established anaphylaxis action plan are more likely to receive it than those without one [50]. This suggests a need for enhanced training for both patients and healthcare professionals. Proper use of epinephrine can delay severe symptoms, providing valuable time for further medical intervention. Although glucocorticosteroids were commonly used in initial management, recent studies suggest they may increase the risk of biphasic reactions as they lack a clear mechanism for systemic relief of anaphylaxis symptoms [51].

Effective anaphylaxis management is crucial as anaphylactic reactions are highly stressful for both children and their parents, potentially impacting long-term mental health. Şengül Emeksiz et al. found that children who experienced anaphylaxis are more prone to have concentration issues, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) [52]. Epinephrine administration remains less common in infants compared to older children or those with known food allergies, though studies confirm its efficacy as the most effective treatment for anaphylaxis [50]. Concerns about adverse reactions to epinephrine may contribute to its underuse, yet serious adverse effects are extremely rare and should not discourage timely administration when indicated. Intramuscular epinephrine is generally safe and provides rapid symptom relief, making it a critical emergency medication. Additionally, adverse food reactions may lead to overly restrictive diets, which can cause nutritional deficiencies and an increased anxiety around accidental allergen exposure [53].

Clinical implications

The study underscores key clinical implications for healthcare providers, especially in paediatric and emergency settings. For instance, the results suggest a need for systematic training in epinephrine use for first responders and general practitioners and for implementing standardized protocols to ensure prompt and effective treatment. Greater awareness among clinicians regarding high-risk factors, such as a history of asthma or hen’s egg allergy, may also improve rapid response in severe cases.

A brief comparison of our findings with international guidelines (e.g., EAACI, WAO) [1, 18] highlights how current practices align with or diverge from established standards in anaphylaxis management. Given the observed underuse of epinephrine in our cohort, adapting protocols and emphasizing its timely administration in clinical settings could improve outcomes in severe paediatric anaphylaxis cases. Clinicians should routinely review the proper storage, carriage, and use of epinephrine autoinjectors (EAIs), and regular EAI training for caregivers and patients has shown to significantly improve their use [54]. Patients should be encouraged to always carry EAIs, understand when and how to use them, and learn proper allergen avoidance strategies to ensure full preparedness for emergencies [55]. Given the complexity and severity of anaphylaxis in young children, education for families and caregivers on how to recognize and respond to anaphylaxis is crucial. Practical training on epinephrine autoinjector usage as well as increased awareness about common dietary allergens would likely empower caregivers to respond swiftly and confidently in emergencies [56].

A focus on preventive measures, such as introducing allergenic foods at an early age as per current recommendations, could reduce the risk of developing food allergies. Additionally, systematic early allergy screenings might be helpful, especially in children with a family history of allergic conditions, to pre-empt severe reactions and ensure prompt intervention where needed.

Study limitations

This study’s retrospective design may present certain limitations, such as potential inaccuracies in medical record documentation, which may be a result of difficulties in proper interpretation and accurate assessment of subjective symptoms in the age group of the youngest children or the relatively small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the reliance on hospital-recorded data may miss cases of anaphylaxis that were either not recognized as such or managed outside the hospital setting.

Conclusions

Our study found that the most common cause of food-induced anaphylaxis was cow’s milk, despite relatively low levels of specific IgE for milk proteins. Therefore, low IgE results should not be interpreted as an absence of risk when introducing this allergen into diet.

In young children, anaphylaxis most frequently manifests with skin and mucosal symptoms. However, it is important to emphasize that neurological symptoms, such as mood/behavioural changes, are not uncommon.

Physicians should be aware that early childhood asthma is a significant risk factor for severe anaphylaxis. Furthermore, raising awareness about the critical role of epinephrine as the primary treatment for anaphylaxis is crucial, especially among general practitioners and emergency personnel.