INTRODUCTION

PASH syndrome (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis) is a rare hereditary autoinflammatory disorder [1]. Classified as a neutrophilic dermatosis, it is characterized by the concurrent presence of three chronic inflammatory skin diseases – pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and hidradenitis suppurativa [2]. The syndrome primarily affects the skin with minimal involvement of joints or internal organs. It is more prevalent in young men with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2 : 1 [3]. PASH syndrome symptoms typically appear in the third or fourth decade of life with acne often emerging as the initial symptom. Lesions from hidradenitis suppurativa usually follow the development of severe acne with pyoderma gangrenosum occurring subsequently [4]. Patients with PASH syndrome often experience exacerbated forms of each of these three conditions. Notably, the full triad of symptoms may be absent at the time of diagnosis, suggesting that the true prevalence of PASH syndrome could be underestimated [5]. The nosological classification of PASH syndrome remains unresolved and its treatment is challenging due to the chronic and recurrent nature of its component diseases. The syndrome is thought to arise from an increased number of CCTG repeats in the promoter region of the PSTPIP1 gene [6]. Treatment typically involves systemic immunosuppression and biological agents, however the literature indicates that standard therapeutic approaches for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) show limited efficacy in managing PASH syndrome [7, 8].

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this work is to document a unique case of PASH syndrome successfully treated with the IL-36 receptor inhibitor, spesolimab, illustrating its therapeutic potential in achieving full remission of symptoms and to provide a comprehensive review of the current literature to highlight the significance of this novel treatment approach in managing refractory cases of PASH syndrome. Based on available data we consider this to be the first documented case worldwide in which an IL-36 receptor inhibitor was successfully employed in the treatment of PASH syndrome.

CASE REPORT

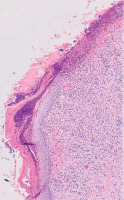

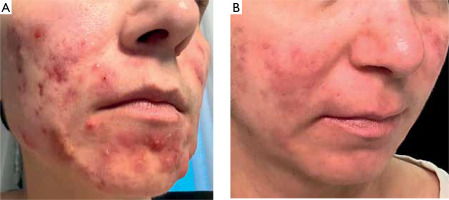

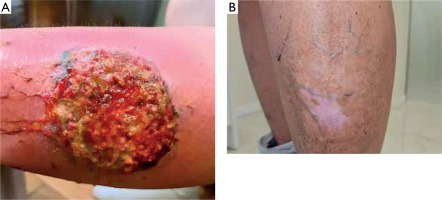

A 38-year-old woman with a history of insulin resistance, obesity (body mass index (BMI) 33.7 kg/m2), severe facial acne (fig. 1) and presenting with axillary hidradenitis suppurativa lesions for 20 years, was admitted to the dermatology department for the diagnosis and treatment of a newly developed ulcer on the left lower leg, which had appeared in the previous month. On admission, physical examination revealed a painful ulcer on the extensor surface of the left lower leg characterized by an irregular, raised edge with significant surrounding erythema (fig. 2). The patient reported rapid ulcer progression. Laboratory tests revealed significantly elevated inflammatory markers with the results presented in the accompanying table (table 1). The clinical presentation of the ulcer suggested a diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum. To confirm, a biopsy was taken for histopathological examination, though the report noted ambiguous microscopic findings (fig. 3). Further diagnostic evaluations were conducted to determine the underlying pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum. Tumour markers (CEA, CA 125, CA 19-9, CA 15-3) remained within normal ranges. Hematologic diagnostics, chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasound showed no notable pathology, except for early-stage nephrocalcinosis. The patient was referred to a gastroenterology department where endoscopic examinations revealed ulcerative colitis (UC), which activity was classified as moderate on the Mayo Clinic score. The clinical triad of pyoderma gangrenosum, hidradenitis suppurativa and acne enabled the diagnosis of the autoinflammatory PASH syndrome in the patient. During hospitalization, intensive immunosuppression was initiated, including intravenous dexamethasone at 4 mg twice daily, oral cyclosporine A at 2.5 mg/kg of body weight, supplemented with magnesium. Additionally, cefuroxime was administered intravenously at 1.5 g twice daily, enoxaparin subcutaneously at 60 mg once daily and metformin at 750 mg in the evening. This regimen resulted in a positive clinical response, reducing C-reactive protein (CRP) levels to 20 mg/l. Upon discharge, maintenance therapy for HS included clindamycin and rifampicin at 300 mg twice daily along with supportive metformin at 850 mg once daily. Treatment for pyoderma gangrenosum continued with cyclosporine at 150 mg in the morning and 100 mg in the evening and oral methylprednisolone at 16 mg daily. Additionally, the patient was instructed to apply a formulation containing adapalene and benzoyl peroxide to the facial skin, combined with daily moisturizing and strict daily photoprotection. Three weeks later the patient returned to the hospital showing signs of reduced efficacy of this therapy. There was worsening of pyoderma gangrenosum and HS lesions in the axillary regions accompanied by intense pain and pruritus significantly impairing daily functioning. Due to limited availability of surgical options and the high risk of pathergy associated with pyoderma gangrenosum, surgical intervention for axillary HS was not recommended. Additionally, coexisting ulcerative colitis contraindicated the treatment with secukinumab for HS. The patient was instead enrolled in a clinical trial evaluating spesolimab’s efficacy for HS. The patient received the drug at a dose of 600 mg administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks. The IL-36 receptor inhibitor proved highly effective not only in reducing HS lesions (fig. 4) in the axillae but also achieving complete remission of pyoderma gangrenosum and significantly reducing facial acne. The clinical activity of UC was reduced to a mild level according to the Mayo Clinic score following therapy. However, the patient declined consent for a repeat colonoscopy, which would have allowed a visual assessment of disease progression. The patient has been on spesolimab therapy for 1.5 years, maintaining remission without exacerbations of PASH syndrome’s components. The treatment was deemed highly effective.

Figure 1

Acne lesions on the face in the course of PASH syndrome before (A) and after (B) therapy with spesolimab. The patient provided consent for the publication of anonymized photographs

Figure 2

Lesions of pyoderma gangrenosum on the left lower leg before (A) and after (B) therapy with spesolimab. The patient provided consent for the publication of anonymized photographs

Table 1

Summary presentation of the patient’s laboratory results

DISCUSSION

A literature review of therapeutic interventions in PASH syndrome is provided in table 2 to highlight the importance of modern therapeutic approaches in the management of refractory cases of this condition. The table includes patient details such as age, gender, BMI, areas affected and types of therapies used, including both pharmacological and surgical approaches. Particular attention is paid to the efficacy of the new therapeutic approach, indicating its potential use in the future.

Table 2

Literature review of therapeutic interventions for PASH syndrome

| No. | Author | Year of publication | Sex and age | BMI | Hidradenitis suppurativa affected regions | Pyoderma gangrenosum affected regions | Severe acne | Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kruczek et al. | This article | Woman 38-year-old | 33.7 | Axillas | Lower left leg | Yes | Spesolimab | Complete remission, over a year without disease recurrence |

| 2 | Feola et al. [37] | 2024 | Man 21-year-old | N/A | Intragluteal fold | Back, lower legs | Yes | Adalimumab | Complete response after 6 weeks of treatment |

| 3 | Marietta et al. [28] | 2023 | Woman 64-year-old | N/A | Inguinal, pubic and vulvar area | In stage of remission after prior Infliximab treatment | Yes | Guselkumab | Treatment did not induce a complete remission but provided clinical stability for a year |

| 4 | Cawen et al. [24] | 2022 | Man 45-year-old | N/A | Axillas, inguinal region | Left leg | Yes | Wide surgical excision, intravenous penicillin, clindamycin and ciprofloxacin, clobetasol ointment | Good response, with cribriform scarring |

| 5 | Sonbol et al. [1] | 2018 | Man 42-year-old | N/A | Axillas | Lower limbs, shoulders and abdominal region | Face, occipitocervical region and scapular region | Cyclosporine, prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil and daily topical clobetasol propionate | Treatment allowed stabilization, with very few new lesions and healing of older lesions |

| 6 | Niv et al. [38] | 2017 | Man 36-year-old | N/A | Lower back, gluteal reglon, axillas | Lower legs | Generalized acne on the back | Dapsone, prednisone, topical clindamycin | Remarkable improvement |

| 7 | Zivanovic et al. [39] | 2016 | Woman 32-year-old | 39 | Axillas, inguinal fold | Lower legs | Yes | Prednisone, dapsone and rifampicin with ciprofloxacin, topical antiseptics and gentamicin | The PG fully epithelialized, while the HS showed improvement with minimal inflammatory lesions |

| 8 | Staub et al. [29] | 2014 | Woman 22-year-old | 36.7 | Axillas, groins, genital and anal area | Lower legs | Yes | Infliximab with cyclosporine and dapsone | Sudden and prolonged improvement |

| 9 | Marzano et al. [18] | 2013 | Man 34-year-old | 28.4 | Inguinal and perianal area, axillas | Chest, and bilateral thighs | No | Infliximab | Mild disease activity persisting in the perianal area |

| 10 | Braun-Falco et al. [40] | 2012 | Man 34-year-old | 31.1 | Axillas | Chest, back, lower legs | Atrophic scars on the face and back | Anakinra | Substantial, but not complete remission |

| 11 | Braun-Falco et al. [40] | 2012 | Man 44-year-old | 33.8 | Axillas, abdominal fold | Lower left leg | Yes | Skin graft, prednisolone, azathioprine and topical tacrolimus ointment | Ulcerations decreased very slowly in size to 1 cm in diameter during a 1-year follow-up period |

At present, there are no established treatment guidelines for managing PASH syndrome [9]. Identifying gene variations is important but insufficient to fully explain pathogenesis in PASH syndrome. Calderón-Castrat et al. identified a PSTPIP1 gene mutation seen in PG without clarifying shared pathways [10] while Duchatelet et al. reported NCTSN mutations implicating the gamma-secretase pathway without fully explaining PASH [11]. Marzano et al.’s whole-exome sequencing study on PASH patients found mutations in MEFV and NOD2 but did not reveal a unifying mechanism [12]. Genetic insights are thus valuable for HS and PG in PASH but currently do not guide therapy selection.

In PASH syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum is a non-infectious skin disorder marked by the rapid onset of painful ulcers that evolve from sterile pustules, featuring irregular, undermined borders and red, inflamed surroundings [13, 14]. These ulcers vary in size and depth, often causing significant pain and systemic symptoms such as fever and fatigue. Although PG’s exact etiology remains unknown, it is frequently associated with systemic conditions including inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis and hematologic disorders like acute myelogenous leukaemia and myeloid metaplasia [15, 16]. Identifying any underlying disorder is essential for effective treatment. Histopathological findings in PG are typically nonspecific, such as sterile dermal microabscesses and neutrophilia, mixed inflammatory infiltrates or lymphocytic vasculitis [17]. Marzano et al. found normal serum levels of IL-17 and TNF-α with elevated levels in skin biopsy samples, indicating localized inflammation [18]. PG often demonstrates pathergy where minor trauma induces PG through the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and IL-8/36 by keratinocytes. Additionally, microdamage can allow microbial entry further complicating the condition [19]. For patients with moderate to severe HS, surgical intervention is often considered [20–22]. However, it is important to note that individuals with PASH syndrome are at an increased risk of pathergy due to the coexistence of pyoderma gangrenosum [23]. According to the case report by Cawen et al., the potential for pathergy presents a significant limitation [24]. Performing three intradermal pricks using a 20G needle on the ventral forearm and assessing the site after 48 hours in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa and severe acne before proceeding with surgery is suggested [25].

In PASH syndrome, autoinflammatory lesions in pyoderma gangrenosum and potential bacterial infection in HS co-occur presenting a clinical challenge. Intensive immunosuppressive therapy carries a risk of severe infectious complications. When using strong immunosuppression alongside antibiotic therapy it is essential to consider that cyclosporine, an immunosuppressant, is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP3A4. Rifampicin used for infection treatment is a potent inducer of this enzyme leading to accelerated cyclosporine metabolism [26]. Consequently, the interaction between these drugs lowers blood levels of cyclosporine potentially diminishing its therapeutic efficacy what occurred in the case described by the authors.

Huang et al. documented a successful response to a regimen combining prednisone, thalidomide, colchicine and doxycycline in a 20-year-old male patient unresponsive to standard treatments [27]. Case studies in the literature suggest that biological therapies may promote sustained remission of skin lesions associated with PASH syndrome. Marletta et al. report that infliximab initially controlled PG and HS. Its use was discontinued after 3 years due to reduced efficacy for HS. A subsequent regimen with adalimumab was also halted due to loss of effect. The patient was then administered guselkumab which decreased purulent discharge but left residual scarred plaques as scars after the healing of PG lesions [28]. Staub et al. report that etanercept, adalimumab, fumaric acid and the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) anakinra had not achieved lasting remission. Significantly, a combination of intravenous infliximab with cyclosporine and dapsone provided sustained clinical improvement [29]. It is important to highlight that secukinumab is contraindicated in patients with coexisting inflammatory bowel disease, a condition frequently associated with PASH syndrome, as also observed in the case described by the authors [30]. This leads to the conclusion that biological drugs targeting TNF-α, IL-23, IL-1 and IL-17 are either not fully effective in PASH syndrome or are contraindicated for its treatment.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of PASH syndrome treated with spesolimab described in the literature. Spesolimab is a humanized antagonistic immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that inhibits signalling via the human IL-36 receptor (IL-36R). By binding to IL-36R, spesolimab prevents subsequent activation by related ligands (IL-36 α, β and γ) and thereby blocks proinflammatory pathways [31]. Spesolimab is currently approved for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis with ongoing clinical trials investigating its potential use in the therapy of hidradenitis suppurativa. Di Caprio et al. demonstrated elevated levels of IL-36α, IL-36β and IL-36γ not only in hidradenitis suppurativa but also in acne lesions compared to healthy skin while levels of IL-36Ra, the anti-inflammatory IL-36 family member remained unchanged [32]. Notably, IL-36 cytokine expression was similar in both conditions, implicating a shared role in the pathogenesis of acne and HS with IL-36γ showing the greatest increase. This prompted an assessment of serum IL-36γ levels, which Western blot analysis confirmed were higher in acne and HS patients than in healthy controls supporting its role in the inflammatory processes of both disorders [33]. The literature reports two publications detailing 3 cases of successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum using spesolimab [34, 35]. Pathergy plays a significant role in PG, where upon skin injury, RNA release activates the innate immune response, leading to neutrophil activation and degranulation. Concurrently, keratinocyte injury induces IL-36 release. This combination triggers IL-36 activation by neutrophil-derived proteases subsequently increasing the expression of pro-inflammatory neutrophilrecruiting cytokines including interleukin-8, TNF, CXCL-8, interleukin-17A and interleukin-6. Spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor antagonist, inhibits these pro-inflammatory downstream effects of activated IL-36 thereby disrupting the inflammatory cycle in pyoderma gangrenosum. Currently, only one study describes the use of the drug in patients with ulcerative colitis. Spesolimab was demonstrated to be generally well tolerated in UC patients, even at a dose of 1200 mg, which is twice the dose administered to the patient described in our report. Spesolimab led to an improvement in the clinical condition of UC patients; however, the efficacy endpoints were not met [36]. The cited evidence from the literature, along with the high therapeutic efficacy observed in the patient described by the authors suggests that spesolimab is well suited to address the pathogenesis of component diseases in PASH syndrome. The patient has been receiving spesolimab therapy at a dose of 600 mg administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks for 1.5 years as part of a clinical trial, during which her HS and PG lesions have remained in remission and the severity of facial acne has shown significant improvement. Spesolimab is an emerging treatment and thus its long-term effects remain unknown. Further studies are essential to assess its long-term safety and to establish a new therapeutic option for patients suffering from this debilitating disease. Nevertheless, the authors emphasize the innovative nature of their findings which introduce an effective therapeutic modality for the challenging-to-treat PASH syndrome.

CONCLUSIONS

In PASH syndrome there is a relapsing nature of the associated conditions. The typical clinical course is more prolonged and complex with loss of response frequently occurring over time. The therapeutic approach to PASH syndrome remains challenging and still there is a lack of the therapeutic algorithm. Considering IL-36 involvement in the pathogenesis of PASH syndrome, spesolimab stands out as a promising therapeutic option capable of targeting the syndrome’s underlying inflammatory mechanisms. By inhibiting the IL-36 pathway, spesolimab reduces inflammation in the affected tissues, representing an innovative and focused treatment approach to PASH syndrome. Nevertheless, further long-term research is essential to assess its sustained safety and efficacy which will be crucial in confirming spesolimab as a dependable treatment for this complex syndrome.