Introduction

“[…] If a peace system can be devised for an entity as large, diverse, and populous as Europe, it can be devised globally. It would be naive to suggest that this is easily achievable. But it would be cynical, in light of the suffering of the war-affected children of the world, to accept war as an inevitable part of the human condition. There are global networks, formal and informal, of health professionals who think about eliminating war and who work to accomplish this”.

Santa Barbara J. [1]

Many countries around the world are currently concerned about the mental health of children and young people [2-5]. The reasons for this are bullying and cyberbullying [6], migration processes in the world, epidemics and pandemics, changes in family structures, constant stress and conflicts [7], insufficient material recourses, world wars, military conflicts [8-10], etc. According to research, 4% of people aged 12 to 17 and 9% of 18-year-olds suffer from depression, which is the most common phenomenon that leads to various negative consequences [11]. Serious mental illness (SMI) includes conditions that are usually debilitating to the brain, behavior and day-to-day functioning [12]. Examples of SMI include major depression, bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders [13]. Psychologically unstable people primarily include people with poor health or immunity, as well as those who are vulnerable to obsession or who are emotionally unstable. Whilst 5.8% of the general population has SMI at any one time, three-quarters of serious mental health problems develop before the age of 25. The prevalence of psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder in young adults (16-24 years of age) over 12 months is 0.5% and 3.4%, respectively [12]. This trend is common in many European and American countries.

Some research [14] is devoted to the formation of a health-preserving environment in an educational institution, among the important priorities of which is the creation of moral and psychological comfort, a favorable and safe space for students’ learning and development. In this context, it is important to point out the cultivation of tolerance, students’ psychological health in the context of inclusion [15], recognition of individual abilities and talents and the uniqueness of each person in the educational process, regardless of developmental characteristics [16].

According to the results of the International Teaching and Learning Survey (TALIS), an ongoing survey of educators conducted by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), "many teachers report that their work is very stressful. The most stressed teachers live in Portugal, England, Hungary and the Flemish community in Belgium. Teachers with the lowest levels of stress live in Georgia, Kazakhstan, Romania. The main reasons for high levels of stress at work are related to excessive workload: too much administrative work, not enough time to prepare for lessons and too many lessons" [17]. Among other things, stressful situations in education are caused by social challenges and realities. For example, COVID-19 or the military situation in modern Ukraine have served (or are serving) as major barriers affecting quality education.

The effects of war bring about significant anxiety among educators and students, hindering their ability to teach or learn effectively. For instance, the constant threat and unpredictability of the situation can lead to symptoms in both children and adults that resemble post-traumatic stress disorder, including sleep disturbances and obsessive thoughts. High anxiety levels also diminish concentration and memory, complicating learning and often resulting in withdrawal, mood swings and communication difficulties. For teachers, these challenges can lead to professional and emotional burnout, psychological discomfort and interpersonal conflicts. Therefore, this article examines anxiety as a key factor affecting the mental health of both students and teachers.

Aim of the work

The aim of the work was to substantiate the state of research on the problem of educators’ mental health and outline the challenges they face in the context of the war in Ukraine; to study the level of students’ and teachers’ anxiety as a component of a person’s psychological imbalance; and to present a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the results of the empirical study.

Material and methods

The study was conducted between March and May 2023 at the Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University (Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine). The survey involved 81 teachers, 148 students aged 12-15 and 137 students aged 16-17 from the Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, Volyn and Lviv regions of Ukraine. The research instrument used to identify the level of personal and reactive anxiety was the Ch. Spielberg and Y. Khanin methodology.

This methodology is also known as the Spielberg-Hanin Anxiety Scale and is used to identify levels of personal and situational (reactive) anxiety. The methodology consists of two separate questionnaires, each of which contains 20 statements. One questionnaire is aimed at assessing situational anxiety, and the other is aimed at assessing personal anxiety. Respondents are asked to rate the extent to which each statement corresponds to their feelings or state at a particular moment (for situational anxiety) or in general (for personal anxiety). To measure the results, responses are graded on a scale from 1 to 4, with each grade reflecting the intensity of the anxiety. The total score for each scale indicates the level of anxiety: low, moderate, moderately high, high. This method was used in the study because it is characterized by high validity and reliability, and the tool is convenient for self-assessment of psycho-emotional state and does not require special conditions for its implementation.

Results

Psychological imbalance in wartime

It is hard to talk about psychological balance in war because at the moment of insecurity, through the stages of war shock, the structure of the brain changes [18], i.e. the activity of cognitive zones that were more actively intellectually engaged before the war, i.e. under normal living conditions, is suppressed. In times of stress and danger, the brain’s rectal zone becomes activated, and a person is focusing more on preserving physiological functions – survival and adaptation to the existing environmental conditions. Psychological balance in such conditions is often replaced by a confusion of emotions, where fear, anxiety and uncertainty are dominant at this period of life [8]. Therefore, it is difficult for people to become engaged in creative, intellectual activities due to excessive fatigue and inability to concentrate. This is largely true for teachers, lecturers, artists and scientists.

Emotional lability is a response to stress and trauma. People may experience dramatic mood changes, from deep depression to uncontrollable outbursts of anger or despair. This volatility makes it difficult to function normally and to interact socially. Social isolation or loss of social networks can result in devastating processes in the human psyche, which also harms the person’s mental health. Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder are most common in countries at war. High levels of mental disorders are also observed in post-conflict countries, where people also suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder according to Długosz [19]. The results of a survey of war refugees from Ukraine show that they experience psychological distress in the form of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety. It was the Russian military aggression on Ukrainian territory, the atrocities and the destruction caused by the full-scale invasion that forced many to leave their places of residence and flee the war, which also led to post-traumatic stress disorder among refugees [9,20].

The study, conducted in Ukraine 18 months after the full-scale invasion of the Russian occupier, involved 929 men and 1,056 women; as such there are reasons to claim some tendencies in the existence and experience of stress and war trauma [21]. In particular, the study attempted to identify the difference between the perception of war trauma, stress and the experience of losses by men and women. Women, who are more emotional and attached to their families and children, have a harder time coping with their loss or separation.

Thus, wars (armed conflicts) harm the human psyche – both men and women face death, numerous physical and mental injuries, fear, despair, etc. It is also worth focusing on the mental feelings of representatives of other genders when a person considers themselves non-binary or genderqueer. In terms of inclusiveness, children with disabilities are among the most affected of all categories of particularly vulnerable persons during a crisis (war): “At the beginning of 2021, there were 163,900 children with disabilities often subject to neglect, limited resources, poor care quality and harmful practices. With the war, there are now even more children with physical disabilities, developmental disorders and emotional disorders. There is an insufficient number of medical support including medicines, institutions, servicesandfinancial supportfor children with disabilities. Children with disabilities in Ukraine are in a particularly vulnerable situation during the war, facing discrimination and exclusion from social life. Due to limited transportation accessibility, many cannot participate in general events and activities. In conflict zones, they face increased risks of injury and trauma” [22].

Impact of war on the mental health of educational process participants

In the context of preserving the health of children with war trauma, as well as fostering self-confidence, trust and stability of values, Marek Rembierz notes: “The destiny of children experiencing the cruelty of war is, unfortunately, an ever-present reality that cannot be effectively eliminated from the realm of the human world as a deliberate evil done by humans. This reality – such as it is as a manifestation of doing evil in its evident form – poses a research and practical challenge for pedagogy” [10].

The study "War and Education. Two years of full-scale invasion", conducted by the International Charitable Foundation SavED together with the VoxPopuli Agency at the beginning of 2024, shows that the majority of educational process participants in Ukrainian schools consider air raids to be the main barrier to students’ learning process [23]. Thus, among the teaching community, 75% of teachers and 87% of school administrators point to this factor. However, among students and parents, this reason was mentioned somewhat less frequently – 47% and 51% of respondents, respectively. In addition, there are difficulties in the learning process in particular: 54% of educators report that students lack concentration, and 43% say they are nervous or anxious. Students mention that "some subjects are harder (44% vs. 20% of teachers), too many subjects (41% vs. 8% of teachers), lack of concentration (33% vs. 54% of teachers) and feelings of anxiety/nervousness (27% vs. 43% of teachers)" [23].

As we can see, the challenges of war have been negatively affecting the process and learning outcomes in Ukrainian educational institutions for three years in a row. Pedagogues often point to apathy, memory problems, obsessive thoughts, impulsive behavior, a sense of hopelessness, guilt, etc., which is also the same among parents. The results of another study conducted by HIAS and NGO Girls on "18 Months Later: A Mental Health and Psychosocial Needs Assessment across Ukraine" indicate the psychological symptoms, including depression [24]. More than half of the Ukrainians questioned1 said they had lost interest in activities that they used to enjoy and are facing challenges in their work or employment: 48% of respondents reported having trouble sleeping, 46% reported feeling sad, 44% indicated constant anxiety, 39% reported fatigue, 31% had trouble concentrating, and 26% had mood swings. For example, the reasons for stress include loss of contact with relatives and even pets; difficulty in getting a higher education and the choice of place of residence; fear of being mobilized after reaching the age of adulthood (in particular because they will not be able to help their relatives) [24]. However, perhaps the biggest factors that provoke stress or even depressive disorders in children and adolescents are the fear of losing their loved ones, being occupied by the Russian military, being deported, being injured by explosions, etc. According to our monitoring, children in the western part of Ukraine, as well as internally displaced persons, seem to have adapted to martial law in the country, but there are some changes in their behavior – they are more likely to be in a sad mood, feel anxious, suffer from sleep disorders, sometimes become withdrawn and unwilling to communicate [9]. It is important to take into account, and both parents and teachers have noticed this, that children have become mature too quickly, they realize the dangers of war and have become more serious.

Anxiety and its impact on the learning process and outcomes: results of an empirical study

The loss of a sense of security is one of the key causes of psychological imbalance during war, and its violation leads to increased anxiety and vulnerability. People are in a constant state of readiness, which depletes their psychological reserve. A review of scientific sources on this issue shows that people suffering from anxiety are characterized by low self-esteem, excessive self-demand, depression, persistent stereotypes and prejudices about the perception of their personality by others, etc. [25]. It is important to distinguish between anxiety as a state and anxiety as a human trait.

Anxiety is a specific condition of a person when he or she feels fear because of a possible danger (real or imagined). Anxiety is a personal trait that shapes an individual’s unique worldview, feelings of despair, and attitudes toward social objects and events. It often involves heightened responses to various life situations, even when circumstances may not warrant such reactions. Anxiety tends to be long-lasting and difficult to overcome, which poses serious threats to teachers and students [26]. This feeling can develop both positive and negative character traits, such as aggression, social depression, emotional dependence and maladjustment. In the study, we focused on the fact that a person’s reaction to socio-psychological stressors can be different depending on the level of situational anxiety, which is closely correlated with personal anxiety. Consequently, we consider personality anxiety as an innate and stable tendency of an individual to experience anxiety. This type of anxiety is usually described as a basic level of anxiety that a person usually experiences regardless of the specific situation. Accordingly, situational or reactive anxiety occurs as a response to specific stressful events or situations, in our case, the war. This state is mostly temporary and can “subside” if the threat is reduced.

To identify the level of personal (PA) and reactive (RA) anxiety in educators, we used the Ch. Spielberg and Y. Khanin methodology [5]. To analyze all the results of the survey, we used the distribution scale presented in Tables 1-2, in which respondents are conditionally divided according to anxiety levels – low, moderate, moderately high and high.

Table 1.

Distribution of educators according to the level of reactive anxiety

| Levels | Scale | f | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0-25 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Moderate | 26-45 | 56 | 69.1 |

| Moderately high | 46-65 | 21 | 25.9 |

| High | >66 | 2 | 2.5 |

Table 2.

Distribution of educators according to the level of personal anxiety

| Levels | Scale | f | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0-25 | 5 | 6.2 |

| Moderate | 26-45 | 41 | 50.6 |

| Moderately high | 46-65 | 31 | 38.3 |

| High | >66 | 4 | 4.9 |

Studies conducted in other countries show that teachers are worried about the challenges and difficulties of working with students in a distance learning environment. The majority of them (n=317, 83.0%) were concerned about the increased possibility of cheating among students during online distance examinations, which is unfair to students. Moreover, they were challenged by the amount of time and effort needed to design examinations and fair assignments (n=229, 59.9%). Furthermore, 59.2% of participants perceived that this teaching strategy led to intrusion of their privacy, i.e. students would contact the teachers at any time of the day irrespective of private personal time (e.g. rest time and family time) [27].

In addition, for example, in Ukrainian universities, according to survey data, teachers also face the problems of student motivation to learn and significant physical and mental fatigue (professional burnout), and long work on e-learning platforms is no substitute for face-to-face communication. Another challenge for educators is that they have to quickly change some teaching methods and switch exclusively to digital educational content, virtual experiments, test surveys, etc.

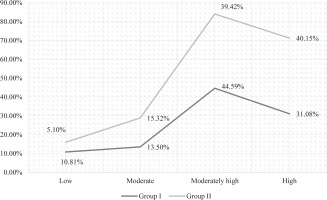

A survey conducted among students of secondary schools in Ukraine made it possible to classify them according to their levels of anxiety (Tables 3 and 4). Among this category of respondents, high and moderately high anxiety in wartime was also identified. At the same time, Group I (respondents aged 12-15) showed somewhat lower levels of anxiety compared to Group II. This is because high school seniors and school graduates were concerned about preparing for the final exams in connection with graduation and admission to higher education institutions (universities). At the same time, the situation of martial law dramatically changed their plans and caused certain difficulties in preparing for the exams, and they studied online for some time. At the same time, not all students approve of this learning format, and some of them are not ready for distance learning. We also attribute the notably high rates of anxiety to young people’s fear for their own lives or the lives of their family members and friends. At the same time, Groups I and II were also concerned about the lack of social communication among their peers, as they were forced to communicate exclusively online or through social media. Online interaction is useful, but only if it is combined with a well-organized teaching methodology in the classroom.

Table 3.

Distribution of students according to the level of reactive anxiety

| Levels | Group I. Students aged 12-15 years old | Group II. Students aged 16-17 years old | Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | % | f | % | % | |

| Low | 16 | 10.81 | 7 | 5.10 | 5.7 |

| Moderate | 20 | 13.51 | 21 | 15.32 | 1.81 |

| Moderately high | 66 | 44.59 | 54 | 39.42 | 5.18 |

| High | 46 | 31.08 | 55 | 40.15 | 9.07 |

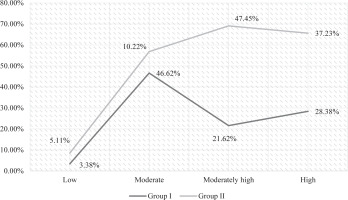

Table 4.

Distribution of students according to the level of personal anxiety

| Levels | Group I. Students aged 12-15 years old | Group II. Students of 16-17 years old | Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | % | f | % | % | |

| Low | 5 | 3.38 | 7 | 5.11 | 1.73 |

| Moderate | 69 | 46.62 | 14 | 10.22 | 36.4 |

| Moderately high | 32 | 21.62 | 65 | 47.45 | 25.83 |

| High | 42 | 28.38 | 51 | 37.23 | 8.85 |

Figures 1 and 2 indicate that older students (ages 16-17) experience slightly higher levels of war-related anxiety compared to younger adolescents (ages 12-15). This difference may stem from their greater emotional maturity and awareness of real-world issues and future prospects. Thus, Group II respondents are more cognizant of the genuine threats posed by war, as well as risks to the safety of themselves and their loved ones. The impacts of war – such as a disrupted future, loss of career opportunities and challenges in achieving life goals – may have long-term effects. Additionally, the unpredictability of war is especially unsettling for older students, adding to their anxiety. Analyzing the results in Tables 3-4, it is evident that 16- and 17-year-olds experience deeper psychological and emotional responses to trauma, recognizing both the moral and social implications of these events.

Both figures indicate that older students (ages 16-17) experience slightly higher levels of war-related anxiety compared to younger adolescents (ages 12-15). This difference may stem from their greater emotional maturity and awareness of real-world issues and future prospects. Thus, the Group II respondents are more cognizant of the genuine threats posed by war, as well as risks to the safety of themselves and their loved ones. The impacts of war – such as a disrupted future, loss of career opportunities, and challenges in achieving life goals – may have long-term effects. Additionally, the unpredictability of war is especially unsettling for older students, adding to their anxiety. Analyzing the results in Tables 3-4, it is evident that 16- and 17-year-olds experience deeper psychological and emotional responses to trauma, recognizing both the moral and social implications of these events.

Discussion

The impact of external conditions on anxiety levels is evidenced by the results of a study conducted among students in other countries, such as Malaysia. Thus, it was revealed that “20.4%, 6.6% and 2.8% of the students experienced minimal to moderate, marked to severe and most extreme anxiety levels, respectively, during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown period. Age, gender, academic specialization and living condition were significantly associated with anxiety levels” [28]. Not only school teachers but also university professors were experiencing fear and psychological anxiety due to the lockdown and strict control measures, social isolation and the new challenges of distance learning. In particular, a study conducted in Jordanian higher education institutions showed that psychological anxiety was also related to the economic impact of the pandemic, fear of losing academic jobs, part-time work, etc. [27]. It is worth mentioning that in developing countries, these psychological fears are well-founded, as the prospects for development and overcoming these negative phenomena are not always clear to citizens. Therefore, educational institutions should provide certain psychological support services for academics in conditions of social isolation and overcoming anxiety. There are also risks for university professors in terms of continuing their research activities, as around 43.5% of the academic staff were bothered by the inability to resume their research activities [27]. Thus, psychological resilience in wartime is largely manifested in the people’s ability to adapt to extreme conditions and find new ways of survival and support. Recovery of psychological balance is possible through the introduction of adequate methods of psychological assistance, ensuring access to resources for recovery and creating conditions for regular social, educational and scientific contacts.

Conclusions

“Stress arises when the combination of internal and external pressures exceeds the individual’s resources to cope with their situation” [2]. The realities of modern life in Ukraine show the educational challenges posed by the military situation. According to our research, the level of such anxiety correlates with the educators’ age: the older they are, the more they worry about their family, work, medical care and the country’s destiny. Psychological imbalances can lead to anxiety symptoms or conditions that harm students’ health and well-being. Depending on the number of symptoms and their severity, students have difficulty concentrating, deteriorate social relationships and fail to learn [29]. Studies of stress in students at various vocational colleges and its connection to various academic, social and other factors show a strong correlation – they “face anxiety and depression, which in turn doesn’t lead to academic success” [2].

As the results of our experiment have shown, the impact of war on the health of teachers and students is significant. As for educators, despite their anxiety, they experience an increased academic workload, as well as an increased emotional workload, which is associated with the need for psychological support for students to deal with their anxieties and stresses. This often leads to burnout, reduced professional efficiency and the emergence of health complications, such as high blood pressure, headaches, sleep disorders, etc. Students, according to the study, experiencing annexation due to hostilities or instability, have problems with concentration, which disrupts their normal life and learning ability, leads to emotional isolation, lower academic results, etc. Therefore, considering these challenges, it is important to provide adequate psychological support for pedagogical interaction participants, introduce stress management programs, provide access to psychological counseling and implement strategies that reduce the academic workload during periods of increased anxiety. The development of integrated programs that include both emergency psychological assistance and long-term support serves as a basis for restoring psychological stability and balance in the face of a prolonged crisis. These measures will help one to cope with the negative impact of anxiety or stress on health and create a more favorable educational environment for learning, education and development in wartime. Thus, the results of the study demonstrate the necessity for a systematic approach to ensuring psychological health in wartime, in particular for educational process participants – students, teachers and parents. UNICEF and other organizations are actively working to provide mental health and psychosocial support to affected children and their caregivers. Efforts include the deployment of mobile units that offer specialized services to help children cope with the psychological effects of the war. However, the need for these services far exceeds the current provisions, and there is a continuous call for increased support to address these urgent needs [30].

High school students (ages 16-17) generally experience greater anxiety about the war than younger adolescents (ages 12-15). This increased anxiety is connected to their heightened awareness of danger, a sense of responsibility for themselves and their families, an uncertain future and a level of emotional maturity that can deepen traumatic experiences. The study’s findings suggest that as students grow older, they develop a clearer understanding of the seriousness of events and become more conscious of potential consequences, which amplifies their anxiety.

We consider the prospect of further research to be interdisciplinary problem-solving in the field of educational health and investment in programs to preserve psychological well-being in educational institutions in crisis (war, pandemic, lack of resources, etc.). The gender dimension – specifically examining differences in anxiety levels between genders – could be a valuable focus for future research. Such an analysis may support a more personalized approach to managing anxiety, as stress responses can vary based on gender characteristics.