INTRODUCTION

Primary cutaneous lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of lymphoid malignancies, with approximately 65% originating from mature T lymphocytes (cutaneous T-cell lymphoma – CTCL), 25% from mature B cells (cutaneous B-cell lymphoma – CBCL), and the remainder from natural killer (NK) cells [1, 2]. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) is a rare T-cell lymphoma affecting the skin, classified within primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. It typically presents as chronic papular or ulcerative lesions, with no extracutaneous dissemination at the time of diagnosis. Histopathological assessment is crucial for the diagnosis [2].

Immunophenotypic evaluation of abnormal cells helps to determine the lymphoma lineage belonging to T-cell or NK-cell. Additional investigations, including monoclonal antibody panels or molecular testing, may be needed in equivocal cases.

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this publication is to present the case of primary cutaneous anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma, emphasizing current diagnostic and therapeutic management recommendations.

CASE REPORT

A 19-year-old male presented on 15 January 2021 with an ulceration on the left thigh. The lesion had appeared approximately one month earlier. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable, and he reported no systemic symptoms. Clinical examination revealed a non-tender skin ulcer with a firm, raised, indurated border on the distal third of the left thigh, resembling ulcerated nodular basal cell carcinoma (fig. 1). No other skin abnormalities were found, and lymph nodes were not enlarged. Additional studies, including positron emission tomography (PET), revealed no pathological findings. Biopsy specimens were taken for histopathological examination.

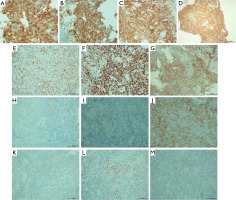

Over the following weeks, the lesion showed progressive regression. The indurated border gradually disappeared, and the central area became smoother (fig. 2). A biopsy sample from the left thigh revealed extensive dermal infiltrate consisting of uniformly looking large cells. The immunohistochemical profile was: CD3 (+++), CD30 (++), CD8 (++), CD5 (+/-), CD4 (-/+), PAX5 (-), CD56 (-), CD245-ALK (-), CD15 (-), MUM1 (-), EMA (-), p53 (20% of positive cells), and Ki67 (+++) with 90% of positive nuclei. The infiltration was in contact with the epidermis. S-100 (-), MART (-), and CD31 (-) were negative.

Figure 2

A, B – Regression of the lesion visible on the patient’s thigh (3 weeks after taking the biopsy for histopathological examination)

The morphological and immunohistochemical findings confirmed primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL), variant CD30(+)/CD8(+)/CD246_ALK(-), with a high Ki67 index indicating high proliferation rate.

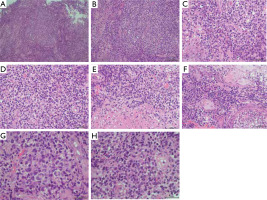

Figures 4 and 5 show the microscopic images of the tissue sample.

Figure 3

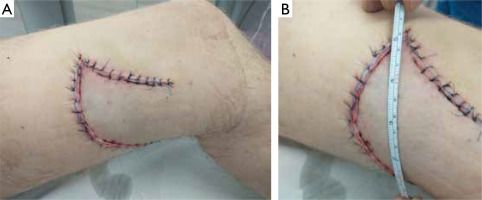

A, B – Postoperative appearance of the lesion on the left thigh after radical excision and coverage with a local rotational flap

Figure 4

Neoplastically altered cells (haematoxylin and eosin staining): A – magnification 5×, B – magnification 20×, C–F – magnification 40×, G, H – magnification 100×

Figure 5

Skin with lymphoma cell infiltration: A – CD30, magnification 40×, B – CD30, magnification 20×, C – CD8, magnification 20×, D – CD8, magnification 20×, E – CD3, magnification 20×, F – Ki67, magnification 20×, G – CD7, magnification 20×, H – CD15, magnification 20×, I – CD20, magnification 20×, J – CD4, magnification 20×, K – ALK, magnification 20×, L – MUM1, magnification 20×, M – PAX5, magnification 20×

Following histopathological confirmation, radical excision was performed on 13 March 2021, and the resulting defect was reconstructed using a local rotational flap, yielding a favorable aesthetic outcome (fig. 3). The patient remained in good general health and was referred to an oncology clinic for the follow-up and consideration of potential systemic therapy. Despite attempts to contact the patient, he did not return, and 6 months later, the medical staff was informed of his death, though the cause was unknown.

DISCUSSION

Primary cutaneous lymphomas are malignant proliferations of T or B lymphocytes, as well as NK cells [1–3]. Based on histopathological features, immunophenotyping, and clinical characteristics, three subtypes of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) are recognized: cutaneous, systemic ALK+ and systemic ALK–. At diagnosis, these lymphomas are confined to the skin, though advanced stages may involve peripheral blood or bone marrow [2].

The current classification of cutaneous lymphomas by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) includes T-cell type (CTCL) and B-cell type (CBCL) [1–3]. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas arise from skin-homing memory T cells (CD4+CD45RO+), which are numerous in many chronic dermatoses, making the diagnosis of skin T-cell lymphomas difficult especially at the early stage of the disease [4, 5].

The aetiology remains unclear, but environmental factors such as ultraviolet radiation, tobacco smoke, and drugs have been suggested, along with the HTLV-1 retrovirus in adult T-cell lymphoma [6]. Cytokine dysregulation, particularly IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, among others, contributes to lymphoma development [7–10].

PC-ALCL is one of the primary cutaneous CD30+ T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, representing the second most common cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (about 30%) [11–14]. It typically affects older patients, with lesions often located on the trunk, face, limbs, and buttocks. Spontaneous regression of lesions is common, and extracutaneous dissemination occurs in 10–20% of cases [12–14].

Treatment involves radiotherapy or surgical excision for localized lesions, and broad range of methotrexate doses (10–60 mg weekly) for generalized cutaneous lesions. Multi-agent chemotherapy is generally avoided [7, 12, 15]. Other therapies, such as anti-CD30 monoclonal antibodies, interferons, and thalidomide, have shown efficacy in refractory cases. The prognosis is favourable, with a five-year survival rate of 90%, though relapses occur in 30% of cases, typically without extracutaneous spread [7, 12, 15].

Accurate diagnosis is crucial to distinguish primary cutaneous ALCL from secondary cutaneous involvement by systemic ALCL, guiding appropriate treatment. Close collaboration between pathologists and clinical oncologists is essential. Continuous vigilance and regular follow-up are necessary, even after complete remission [12, 13, 15].

CONCLUSIONS

PC-ALCL presents a rare yet significant diagnostic challenge. Diagnosis should be considered in chronic nodular skin lesions, and clinical oncologists disease follows a dynamic local course, prognosis remains favourable. Spontaneous regression occurs in 25% of cases, and relapses occur in about 30%, typically without extracutaneous spread. Ongoing research continues to explore more specific therapies for this condition.