Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) comprises a diverse range of rare neoplasms primarily involving T-lymphocytes with a skin tropism. This distinguishes CTCL from nodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mainly of B-cell origin. Notably, around 75% of primary cutaneous lymphomas originate from T-cells, and amongst these, mycosis fungoides (MF) or Sézary syndrome (SS) account for approximately two-thirds of cases [1].

MF, the most common subtype of CTCL, typically progresses at a slow pace, with skin lesions that are stable or evolve slowly. In advanced stages, these manifestations may extend beyond the skin, potentially involving lymph nodes, blood circulation, and less commonly, other organ systems. Advanced stages can also witness a process known as large cell transformation [2]. In contrast, SS represents an erythrodermic and leukemic variant of CTCL and is characterized by extensive peripheral blood involvement, itching, thickening of the skin on palms and soles, erythroderma, and frequently, lymphadenopathy. A characteristic feature of SS is the presence of clonally related malignant T-cells with cerebriform nuclei, known as Sézary cells [3].

The varying stages of CTCL possess substantial potential to impact the quality of life (QoL), even during the early stages of the disease, emphasizing the necessity not to overlook such impacts. Furthermore, itch, strongly associated with dermatology-specific quality of life, can serve as a comprehensive indicator of the overall QoL index [4].

Aim

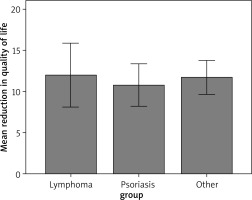

The aim of the study was to compare the reduction in quality of life among patients with MF to those with another chronic skin condition characterized by similar lesions, namely psoriasis vulgaris, as well as to patients with other dermatological disorders.

Material and methods

Recruitment of participants was systematically conducted at the University Centre for General and Oncological Dermatology, Wroclaw Medical University from May 2021 to August 2024 for patients with MF/SS and in April 2024 from the rest of the patients. The study’s cohort included 104 patients, including 16 with verified MF and 1 with SS. There were also 34 patients with psoriasis and 53 with other dermatological diseases: pemphigus vulgaris (5), erysipelas of the lower extremity (4), chronic urticaria (4), classic shingles (4), scarring alopecia (4), systemic lupus erythematosus (4), eczema (3), scabies (3), pruritus (2), dermatitis (2), pemphigoid (2), morphea (2), and 1 case of ichthyosis vulgaris, squamous cell carcinoma of the ear, Grover’s disease, pyoderma gangrenosum, Hailey-Hailey disease, vein thrombosis, Duhring’s disease, drug eruption, nervous system syphilis, dermatoporosis, cutaneous fungal infections of the scalp, vascular purpura, porphyria cutanea tarda, and nodular prurigo. Among patients diagnosed with MF/SS, there were 15 males and 2 females, with ages ranging from 43 to 78 years. 14 out of 16 (87.5%) patients with MF who participated in the study had MF at a stage lower than IIB. In the group of patients with psoriasis, there were 20 males and 14 females, aged between 18 and 68 years with PASI ranging from 6 to 24. Among patients with other dermatological conditions, there were 21 males and 32 females, with ages ranging from 18 to 81 years.

For this study, the Polish language variant of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire, developed and validated by the Wroclaw group, was employed [5]. The DLQI questionnaire comprises 10 items, each rated on a scale from 0 to 3, with response options spanning from “not at all” or “not relevant” to “a little”, “quite a lot” and “very much”. This instrument evaluates several dimensions, including emotional distress, physical discomfort, interpersonal and social relationships, public perception, recreational activities, caregiving responsibilities, impact on work or studies, additional household duties, and financial expenditures, all reflecting experiences within the prior month. The DLQI yields a total score ranging from 0 to 30. Scores are interpreted as follows: 0–1 indicates no impact, 2–5 a small impact, 6–10 a moderate impact, 11–20 a very large impact, and 21–30 an extremely large impact on the patient’s QoL.

The DLQI was conducted on the first days of hospitalization. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Wroclaw Medical University and was conducted in full compliance with the ethical guidelines outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to their enrolment in the study.

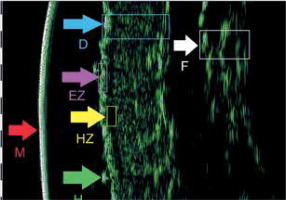

Furthermore, we conducted a pilot high frequency ultrasound (HFUS) study on a single patient, whose DLQI score and photographs of HFUS examination (Figure 1) are also presented in the manuscript.

Figure 1

HFUS picture – the broad band hypoechogenic zone interpreted as infiltration under epidermis terms in alphabetical order: D – Dermis, EZ – Entrance Zone, F – Fascia, H – Hair, HZ – Hypoechogenic Zone, M – Membrane [26]

Results

In the first step of the data analysis, descriptive statistics of research indicators, i.e., result of QoL questionnaire (the interpretation of which means a reduction in QoL index) (Table 1). To determine the shape of the obtained distribution, statistics such as range (min.–max.), measures of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation), measures of asymmetry and concentration (skewness, kurtosis), and normality tests of the distribution were calculated. To check whether the obtained distributions differed from the theoretical normal distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk tests were used as suggested for relatively small sample sizes [6]. The obtained statistical values indicated that the variable showed significant deviations from the normal distribution. These discrepancies can be considered minor because the skewness and kurtosis did not exceed the value of ±2 [7].

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of the DLQI index (N = 104)

| R | M | SD | Mdn | Sk | Kurt | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction in quality of life | 0–29 | 11.46 | 7.37 | 10 | 0.66 | –0.56 | 0.12** |

Intergroup differences

To answer the question of whether the study group (independent variable grouping: lymphomas, psoriasis, other diseases) differentiated the result of reduced QoL (dependent variable), an intergroup comparison was carried out using the Kruskal-Wallis H test. This test was chosen since there were significant discrepancies in the results in the subgroups in relation to the normal distribution. Therefore, the basic assumption regarding the analysis of quantitative data was not met [8, 9].

As can be seen in Table 2, the results of the analyses obtained did not show any statistically significant differences. In the absence of the main effect, no post hoc analyses were performed. This means that the fact of belonging to the study group did not affect the QoL level (Figure 2, Tables 3 and 4), but it is noteworthy to mention that all dermatological diseases were associated with reduced QoL.

Table 2

DLQI of the respondents with lymphoma, psoriasis and other dermatological diseases

| I: lymphoma (n = 17) | II: psoriasis (n = 34) | III: other diseases (n = 53) | H(2) | P-value | ε2 | Post-hoc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mdn | Mrang | Mdn | Mrang | Mdn | Mrang | |||||

| Reduction in quality of life | 11 | 54.32 | 10 | 49.59 | 11 | 53.78 | 0.48 | 0.788 | 0.005 | No data |

Table 3

The range of DLQI scores among respondents with lymphoma, psoriasis, and other dermatological conditions

Discussion

MF and SS have been extensively investigated for their impact on patients’ QoL and are recognized as debilitating diseases. The review conducted by Jonak et al. [10] has demonstrated significant negative effects of these conditions on both physical and mental health. Furthermore, the existing literature suggests that dermatological diseases, in general, have a substantial negative impact on patients’ QoL [11–13]. These findings are in line with our results, which showed that all patients with CTCL exhibited a diminished QoL as assessed by the DLQI questionnaire.

Patients with MF/SS experience profound emotional and social consequences, including feelings of frustration, depression, helplessness, and social isolation [10]. Due to the chronic nature of the disease, the visibility of skin lesions, and the time-intensive yet often insufficient treatment options, CTCL disrupts patients’ everyday lives [14]. Individuals with MF/SS frequently struggle with performing daily activities, traveling, and participating in sports or recreational activities. The disease also significantly affects personal relationships, family dynamics, educational pursuits, and career development, with social engagement becoming increasingly limited [15]. Moreover, the diagnosis of MF, particularly in its early patch and plaque stages, is notably challenging due to its non-specific clinical and pathological features, which frequently resemble those of benign dermatologic conditions [16]. The overlapping characteristics of MF/SS with reactive inflammatory processes complicate its differentiation from disorders such as eczema, psoriasis, parapsoriasis, or atopic dermatitis (AD) often resulting in significant diagnostic delays [17–19].

Retrospective studies highlight a median diagnostic latency of 3 to 4 years following symptom onset, with rare cases showing delays exceeding four decades [20, 21]. The insidious onset and gradual progression of MF, coupled with its highly variable clinical and histopathological presentations, contribute to frequent misdiagnoses and repeated delays in achieving a definitive diagnosis. This indicates that the diagnostic process alone may have a substantial negative impact on the QoL in patients with CTCL.

Moreover, it is challenging to classify MF accurately within the traditional Tumor-Nodes-Metastasis-Blood (TNMB) staging system. A key limitation of using the TNMB staging system for MF is the challenge of accurately assessing body surface area (BSA) involvement. In early-stage MF, the system categorizes lesions into two groups: less than 10% (T1) and greater than 10% (T2) of total BSA. However, this approach does not capture significant variations in disease burden, such as the difference between patients with 20% BSA involvement and those with 50–70% [22].

Next, the modified Severity-Weighted Assessment Tool (mSWAT) is a valuable tool for assessing MF/SS, where multiple lesion types can coexist in a patient. It quantifies disease severity by calculating the percentage of BSA affected by patches, plaques, and tumours, with relative weights of 1, 2, and 4, respectively. BSA is often estimated using the palmar surface (1% BSA) [23]. However, mSWAT has limitations as it is subjective and influenced by the physician’s experience [24]. Additionally, the weighting of tumours is debated as they carry a higher prognostic value due to denser dermal infiltrates and greater neoplastic cell content, potentially under-representing tumor burden compared to patches and plaques.

Due to the challenges in diagnosing and assessing disease severity in patients with MF/SS, recent reports have highlighted the potential utility of high-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) in this context [25–28].

Wohlmuth-Wieser et al. [25] measured epidermal, subepidermal low-echogenic band (SLEB), and dermal thickness, comparing CTCL patients with those with AD and psoriasis. The study demonstrated increased epidermal thickness in CTCL and psoriasis compared to AD. Moreover, Polañska et al. [26] also observed a reduction in SLEB thickness following phototherapy in patients with MF utilizing HFUS. The study concluded that routine assessment of SLEB thickness may serve as a valuable adjunct for monitoring therapeutic response. On the other hand, Wang et al. [27] described the morphological characteristics of MS in HFUS including the uniformity of the epidermis as well as the presence of internal echoes and echogenic foci. Nevertheless, despite promising findings, the limited number of studies on the utility of HFUS in the diagnosis and monitoring of CTCL patients highlights the need for further research to establish HFUS as a standard tool in routine clinical practice. Our experiences have also confirmed that HFUS, a safe and cost-effective diagnostic tool, objectively enables the measurement of infiltration intensity in MF/SS [28] (Figure 1).

Additionally, the chronic pain and unpredictable progression of MF/SS lead to substantial challenges in maintaining employment as many patients face difficulties in fulfilling their work-related duties. Overall, MF/SS exerts a considerable impact on key domains of life, underscoring the need for more effective therapeutic approaches and comprehensive patient support [29]. Studies examining MF/SS patients have reported DLQI scores ranging from 5.0 (4.8–5.5), 6.3 (±6.7), 3 [1–10], 12 (±8) to 13 [8–18], suggesting a small to moderate impact on QoL [30–34]. These findings highlight the variability in QoL impairment across MF populations, contrasting with other studies reporting more severe effects, and emphasize the need for individualized patient management. In our study, the DLQI scores for MF/SS patients range from approximately 2 to 22 points with a median range of 10 (Table 2), which is consistent with the results of current literature. Moreover, it is important to note that changes in DLQI scores in patients with MF/SS also provide valuable information for physicians regarding the severity and progression of the disease. These changes should be carefully monitored, just like other tools used to assess disease severity.

Furthermore, a recent study introduces an adjustment to the overall DLQI scores by accounting for responses marked as “not relevant” giving rise to the DLQI-R. This revised instrument, developed by Rencz et al. [35], enhances the discriminatory power of the DLQI by incorporating the informational value of “not relevant” responses. The DLQI-R scoring methodology offers greater precision in the assessment of health-related quality of life, thereby demonstrating substantial applicability in both clinical practice and research settings. This revised version of the instrument may also be more suitable for patients with CTCL.

Also, given the age of onset for CTCL, Skindex-29 may be a more suitable and reliable tool for assessing QoL in these patients as it was compared to DLQI in a study by Paudyal et al. [36]. Participants in that study were generally satisfied with the length and layout of both questionnaires but favoured Skindex-29 for its clarity, longer recall period, and broader emotional scope. Both measures were noted to omit key aspects, such as the impact on professional relationships, but Skindex-29 was perceived as more reflective of participants’ lived experiences.

In addition, the comparison of DLQI before and after treatment in patients with CTCL is the focus of an increasing number of studies [30–32, 34, 36–38]. In the investigation conducted by Terhorst-Molawi et al. [30], the potential involvement of mast cells, eosinophils, and their mediators in MF-associated pruritus and disease severity was assessed. The study included 10 patients with early-stage MF (IA–IIB), comprising 4 patients with pruritus and 6 without. The median DLQI for the pruritus group was 5.0 (interquartile range: 4.8–5.5), while the median DLQI for patients without pruritus was 0.0 (interquartile range: 0.0–0.8). The study indicates a significant role of pruritus in reducing the QoL in patients with CTCL. In another prospective study conducted by PruNet (the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Network on Assessment of Severity and Burden of Pruritus), involving 15 patients with MF/SS, the mean DLQI score was 12.1, consistent with findings from our study. The study also included 181 patients with psoriasis, with a median DLQI score of 10.6. Across a total of 534 patients with various dermatological conditions, the mean DLQI score was 10.3, underscoring the considerable impact of skin diseases on patients’ QoL [33]. This study also illustrates the significant challenges in recruiting adequate numbers of patients with MF/SS for research studies. A comparative study by Ayyalaraju et al. [31] examined the impact of hospitalisation on the QoL in patients with severe dermatological conditions in the United Kingdom and the United States. The study included 366 patients from the US, of whom 14% (51 patients) were diagnosed with MF. The initial mean DLQI score for patients with CTCL was 6.3, followed by a second score of 6.2. These results suggest that the DLQI may be suboptimal for accurately assessing QoL in CTCL patients as it may not fully capture the unique symptoms and disease burden associated with CTCL. Conversely, in a cohort of 109 psoriasis patients from the UK, the mean baseline DLQI score was 13.7, which decreased to 6.2 after treatment. Among US psoriasis patients, the mean baseline DLQI was 14.6, which declined to 8.3 following intervention. These findings indicate a substantial post-treatment improvement in QoL for both cohorts, with a slightly greater improvement observed in the UK patient group. Patients with CTCL should have been stratified by staging and analysed in subgroups. In our study, we also did not undertake this approach due to the small number of CTCL patients (n = 17).

In a research letter by Nawar et al. [34], the authors investigated the QoL changes in patients with MF and SS and assessed both short- and long-term effects of low-dose total skin electron beam therapy (TSEBT). This prospective study included patients who received a median TSEBT dose of 12 Gy, delivered through a modified six-dual-field technique. The baseline DLQI score prior to treatment had a mean of 13 (range: 8–18). By the final day of radiation therapy, this score decreased to a mean of 8 (range: 3–13), with a further reduction to 6 (range: 2–10) at 6 months post-treatment. TSEBT produced a significant reduction in DLQI scores, with a mean difference of 3.96, and this improvement in QoL was sustained for up to 24 months relative to pretreatment scores. The study by Jennings et al. [32] investigated the effect of low-dose TSEBT combined with topical mechlorethamine in patients with MF. In the study, the DLQI was performed in 5 patients before treatment and in 7 patients after treatment. The first mean DLQI of CTCL patients was 6.60 (1–18) before treatment and 4.29 (1–8) after treatment, indicating very good clinical effects of this combination therapy with a median time to progression of 22.7 months. Next, in a subsequent prospective, randomized clinical trial by Graier et al. [37], patients diagnosed with stage IA to IIA MF received psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy administered twice weekly over a period of 12 to 24 weeks. A cohort of 24 early-stage MF patients completed the DLQI questionnaire at three distinct intervals: pre-treatment, post-final PUVA session, and following the entire treatment course. Prior to therapy, 29% of patients (7 of 24) reported no QoL impairment (DLQI 0–1), 17% (4 patients) reported severe impairment (DLQI > 10), 29% (7 patients) experienced moderate impairment (DLQI 6–10), and 25% (6 patients) noted slight impairment (DLQI 2–5) attributable to MF. PUVA therapy resulted in a statistically significant reduction in mean DLQI scores, decreasing from 5.83 ±4.92 to 2.41 ±2.56, marking a 58.6% improvement (p = 0.003). These improvements in QoL, alongside enhancements in psychological well-being, were sustained independent of the administration of maintenance therapy. In another study by Vogiatzis et al. [38] investigated the impact of extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) on QoL and disease progression in patients with MF and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). The study was completed by 10 patients with MF. Prior to treatment, the DLQI scores ranged from 0 to 23, with a mean of 9.7. Following ECP, the DLQI scores ranged from 0 to 10, with a mean of 3.0. The findings of the study demonstrate that patients with MF exhibited a significant reduction in the use of pharmacological treatments for their underlying condition. However, it must be mentioned that 2 out of the 10 MF patients progressed from stage IIA to IIIA.

This study has certain limitations; the recruitment of a larger cohort of patients with MF or SS remains challenging due to the rarity of these conditions. Patients with MF/SS should have been stratified by staging and analysed in subgroups, but we did not undertake this approach due to the small number of MF/SS patients (n = 17).

Consequently, further research is warranted to expand the evidence base in this area.

Conclusions

This study highlights the significant impact of CTCL, particularly MF and SS, on patients’ QoL. The findings demonstrate that the chronic character and inevitable progression of the disease are critical factors contributing to QoL impairment as indicated by median DLQI scores that reflect varying levels of emotional and physical distress. These results are consistent with the existing literature, which reports considerable variability in QoL across different populations of MF patients, underscoring the necessity for individualized management strategies.

Although the study’s sample size was relatively small and no statistically significant differences were observed between the DLQI scores of patients with CTCL and those with psoriasis or other dermatological disorders, the chronic nature of CTCL was shown to have a substantial impact on daily activities, emotional well-being, and social interactions.

Furthermore, therapeutic interventions such as low-dose TSEBT and ECP showed promise in improving QoL and reducing the reliance on pharmacological treatments. Nonetheless, disease progression remains a critical concern as evidenced by the 2 patients who advanced to a higher stage. Thus, ongoing research is essential to explore effective treatment modalities and comprehensive support systems aimed at addressing the multifaceted challenges faced by patients with CTCL, ultimately striving to enhance their overall QoL.

Moreover, HFUS shows significant potential as a non-invasive tool for diagnosing and monitoring TCL by providing detailed assessments of epidermal and dermal features. Studies have demonstrated its utility in measuring epidermal thickness, SLEB changes, and morphological characteristics, which could aid in tracking therapeutic responses. However, further research is needed to validate its efficacy and establish HFUS as a standard diagnostic and monitoring method in routine clinical practice for CTCL.