Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) features recurrent pruritic wheals/angioedema persisting > 6 weeks, with complex aetiology and incompletely understood pathogenesis [1]. CSU usually demonstrates peripheral blood eosinopenia [2–4], with ~10% of patients exhibiting eosinopenia correlating with heightened disease activity, autoimmune features, and reduced treatment responsiveness [5]. Conversely, eosinophilia is rare in CSU but may indicate underlying aetiologies and complicate management.

We report the refractory CSU case with marked eosinophilia and its successful treatment with diagnostic antiparasitic therapy, providing insights for clinical management.

This case report concerns a 32-year-old woman with a 7-year history of recurrent spontaneous wheals lasting less than 24 h, whose symptoms were previously well-controlled with routine antihistamines. In July 2024, she suddenly experienced a generalized exacerbation of urticaria, with some wheals lasting longer than 24 h and leaving pigmentation upon resolution. The antihistamines she had previously taken were no longer effective. She visited the hospital and was diagnosed with CSU (UAS: 5–6). Laboratory tests revealed eosinophilia (Eos: 2.12 × 10⁹/l) and elevated IgE (138 IU/l). The patient denied any prior history of eosinophil abnormalities in blood tests. Initial treatment with quadruple-dose ebastine was unsuccessful, but intramuscular dexamethasone acetate (Depo-Medrol) temporarily controlled symptoms and normalized eosinophil levels. However, symptoms recurred in August 2024 with prolonged wheal duration (> 24 h) and hyperpigmentation. Omalizumab (300 mg/month) was then initiated, but after 1 month, symptoms only slightly improved (UAS: 4–5).

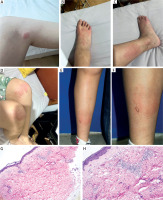

The patient was referred to the Urticaria Centre of Reference and Excellence (UCARE) at Southwest Hospital, Army Medical University. Physical examination revealed new-onset wheals (Figures 1 A–D), some lasting over 24 h and resolving with hyperpigmentation. She also showed atopic signs such as periorbital hyperpigmentation (Dennie-Morgan folds), flexural hyperpigmentation and dermatographism. Her medical history included hand eczema and allergic rhinitis, with a family history of atopy (father: allergic rhinitis; grandfather: allergic rhinitis and senile atopic dermatitis). Repeat tests showed eosinophils (Eos) (0.88 × 109/l) and total IgE (169 IU/l). A biopsy of a persistent wheal (Figures 1 E, F) revealed full-thickness dermal perivasculitis with eosinophil infiltration (Figures 1 G, H), excluding vasculitis. Further tests (ANA, CRP, thyroid autoantibodies, ASST) were negative. A bone marrow biopsy, performed due to recurrent eosinophilia, showed hypercellular marrow with granulocytic hyperplasia and elevated eosinophils, but no abnormal blasts or leukemia-associated abnormalities.

Figure 1

Clinical and histopathological features of the patient. A-D – New-onset urticarial lesions during consultation at our hospital, demonstrating polymorphic, variably sized erythematous wheals with associated post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in some areas. E, F – Biopsy site of a persistent wheal. G, H – Histopathology revealing perivascular inflammation with prominent eosinophilic infiltration (H&E staining, ×200)

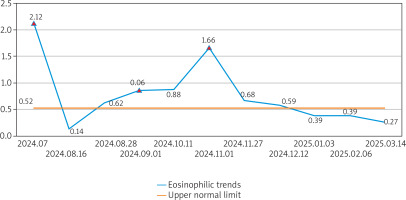

She was still diagnosed with CSU and continued omalizumab therapy. One month later, symptoms persisted (UAS7: 14; UCT: 8) with rising Eos (1.66 × 109/l) and IgE (411 IU/l). A history of raw fish consumption raised suspicion of parasitic infection, but schistosoma antibody and stool tests were negative. Empirical antiparasitic therapy (albendazole 400 mg/day × 3 days) was given. Two weeks later, symptoms improved markedly (UAS7: 5; UCT: 14), with wheals resolving within 24 h and without hyperpigmentation. Eosinophils normalized (0.68 × 109/l). One month later, CSU symptoms nearly resolved (UAS7: 0–1), the disease was in complete remission (UCT: 16), and symptoms remained stable during subsequent 3 months of omalizumab maintenance, with sustained normal eosinophil counts (< 0.5 × 109/l) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Dynamics of eosinophil levels during disease progression and treatment. The blue trend line illustrates serial eosinophil counts (×109/l) throughout the patient’s clinical course. The yellow horizontal line indicates the upper limit of normal eosinophil levels. Three red triangles mark critical therapeutic interventions: first intramuscular glucocorticoid injection; initiation of omalizumab therapy; diagnostic antiparasitic treatment (albendazole)

In our case, the patient initially responded to antihistamines, and the sudden exacerbation of the disease may be associated with the abrupt and marked increase in eosinophil counts. Although active atopic disease is one of the factors that can induce eosinophilia [6], this patient has only a history of atopic disease without current symptoms. Therefore, this cannot explain the current marked eosinophilia. Eosinophilia is rarely seen in CSU patients [2–4], though this case showed markedly elevated eosinophils (2.12 × 109/l), necessitating exclusion of hematologic disorders [7]. Extensive testing excluded immune disorders and hematologic malignancies. Despite negative schistosoma serology/stool tests, raw fish exposure, eosinophilia and IgE elevation suggested potential parasitic infection. With the patient’s informed consent, we trialled short-term anti-parasitic therapy. The eosinophil count then dropped significantly, and the CSU treatment response improved markedly. This suggests that parasitic infection-induced eosinophilia may have caused the sudden worsening and treatment resistance of the CSU symptoms in this case.

Urticarial lesions in CSU typically resolve within 24 h without pigmentation, consistent with the patient’s prior episodes. However, recent lesions persisted > 24 h and induced pigmentation. Histopathological examination excluded urticarial vasculitis, confirming CSU with pigmentation based on clinical and historical findings. Approximately 20% of CSU patients develop pigmentation, defining a hyperpigmented subtype [8]. While the aetiology remains unclear, mast cell-derived mediators directly stimulate melanocyte proliferation/migration [9], and eosinophil-mast cell interactions are documented [10, 11]. This case suggests that markedly elevated/overactivated eosinophils may amplify mast cell activity, potentially explaining pigmentation pathogenesis.

This case shows that CSU patients who initially respond well to H1 antihistamines may later experience sudden symptom exacerbation due to new triggers (e.g., parasitic infection), with changes in skin lesion characteristics (e.g., UV-like lesions) and resistance to H1 antihistamines or even omalizumab. It also highlights that when encountering CSU patients with unexplained significant eosinophilia, parasitic infection should be considered after excluding other causes. Relevant tests should be conducted if possible; otherwise, diagnostic antiparasitic therapy can be considered as a viable option when needed.