Introduction

Radiotherapy is one of the most popular cancer treatment methods, using ionizing X-rays with high ionization energy. Ionization energy causes electrons to be ejected. As energy increases, the ability of the rays to penetrate the skin improves, which helps reduce the dose. Cells undergoing division are most susceptible to radiation. Cancer cells have a higher division frequency than healthy cells, making them more susceptible to damage caused by radiotherapy [1].

Therapies using ionizing radiation are characterized by local effects and are limited to places where cancer lesions occur. The aim of the treatment is to induce specific but desirable therapeutic effects [2]. They lead to biological effects such as damage to cell membranes and DNA, impairing their ability to divide and carry out metabolic processes or causing immediate cell apoptosis. Radiotherapy can be used as a standalone form of treatment or as a supportive therapy to chemotherapy [3].

Unfortunately, the use of radiotherapy also causes side effects, in the epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Skin reactions after radiotherapy can be divided into early and late reactions. Early reactions usually appear within a few weeks of starting treatment and are characterized by excessive skin dryness, pigmentation disorders, erythema and hair loss. As a result of exposure, sebaceous and sweat glands, hair follicles and pigment cells are damaged. The body produces more pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins 1 and 6, transforming growth factor b (TGF-b) and tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-a) [4]. Erythema is a photochemical skin reaction, which results from damage to the spinous layer of the epidermis, denaturation of proteins in this layer, and the release of histamine, which dilates blood vessels and results in skin hyperaemia. The duration of erythema depends on the dose and frequency of radiation exposure. The consequence of erythema is exfoliation and thickening of the epidermis.

In the early stage of post-radiation reactions, we observe exfoliation of the epidermis, which occurs as a result of damage to keratinocytes in the basal layer, accompanied by itching. Dry exfoliation turns into wet exfoliation, accompanied by the exudation of serous fluid. Another early reaction is the permanent dilation of blood vessels, i.e., the development of telangiectasia.

Late reactions occur several months after the end of therapy and are caused by the reaction of fibroblasts to radiation. Fibroblasts are cells characterized by low proliferation potential. With the degradation of collagen fibres, atrophic changes appear in the skin. Increased synthesis of collagen with an irregular arrangement of fibres contributes to the appearance of thickening and fibrosis of the skin tissue, and the skin loses its elasticity [5].

Ionizing radiation, which is used in cancer radiotherapy, is responsible for the formation of free oxygen radicals (reactive oxygen species – ROS), which interact with biomolecules. They contribute to the development of the above-mentioned radiation reactions in the skin and subcutaneous tissue [6, 7].

Aim

The aim of the study was to assess skin tolerance and the effectiveness of a cosmetic preparation whose main active ingredient was fish collagen, as well as to select the remaining ingredients in such a way as to minimize the occurrence of side effects of oncological therapy after radiotherapy.

Material and methods

The cosmetic preparation collagen laminate obtained by ultrafiltration was tested on patients who underwent therapy at the University Hospital in Zielona Gora and who underwent radiotherapy. Patients are currently no longer undergoing treatment. The research group of 50 women suffered from breast cancer (n = 50). Before the experiment, the patients’ skin was examined to diagnose its condition (zero condition). The study was conducted with the consent of the Bioethics Committee in Poznan (consent number 692/23). Each participant received a commercial cosmetic preparation. People who underwent radiotherapy applied the cosmetic to the area exposed to radiation, i.e., their breasts. Patients used the preparation twice a day, in the morning and in the evening. The preparation was used to eliminate skin reactions to oncological treatment. The study lasted 6 months. The test subjects came mainly from small towns and villages in the Lubusz Voivodeship. The average age in the study group was 54 years (age range: 35–74 years). Digital measurements were performed monthly using a Courage + Khazaka Electronic GmbH device to measure hydration, transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and pH value. Patients were asked to wash their skin with water, then wait 10 min before applying the preparation. The above-mentioned skin parameters (stratum corneum) were measured using probes. The experiment was conducted with the patients’ informed consent. They were also interviewed to provide information about their health and skin condition. Patients used a commercial collagen laminate cream that contained the following INCI ingredients: Aqua, Pectin, Collagen (Soluble Collagen), Saccharomyces Cerevisiae (Yeast Hulls)/Hexapeptide-11 Ferment Lysate, Pyrus Malus Fruit Extract/Pectin, Lactobionic Acid, Linum Usitatissimum Seed Extract, Gluconolactone, Panthenol, Polysorbate 20, Citric Acid, Trisodium Ethylenediamine Disuccinate, Calcium Gluconate, Sodium Benzoate, Potassium Sorbate.

Results and discussion

Figures 1–3 show the average variation in the levels of hydration, transepidermal water loss and skin pH value, before the application of the tested formula and throughout the entire study. Measurements were performed once a month. All parameters were measured in a group of 50 people at the site exposed to radiation, i.e., the pedestrian area.

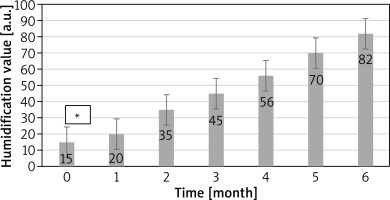

Figure 1

Change in the level of skin hydration of patients after the first use of the preparation and during its use after radiotherapy. **p < 0.01 – significant increase from month 1 to 6 (W6) based on the post-hoc test. Group size test (n = 50)

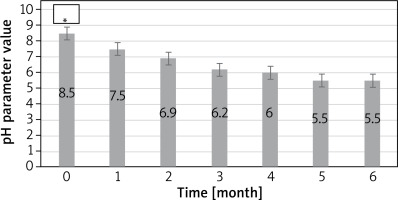

Figure 3

Change in the pH value of the patients’ skin after the first use of the preparation and during its use after radiotherapy. **p < 0.01 – significant increase from month 1 to 6 (W6) based on the post-hoc test. Group size test (n = 50)

Hydration level

The average degree of hydration of the epidermis before laminate application and after 1–6 months is shown in Figure 1. Based on the above graph, it can be seen that all people who participated in the study had better results in the hydration level as the experiment progressed. Table 1 presents the interpretation of the results of the discussed parameter. Changes in the hydration level ranged on average from 15 to 82 a.u.

Table 1

Interpretation of epidermal hydration measurement results

| The degree of hydration of the epidermis | Measurement result |

|---|---|

| Very dry skin | < 30 |

| Dry skin | 30–45 |

| The skin is sufficiently moisturized | > 45 |

Already after the first use, the device’s skin hydration level increased by 5 a.u. In the next month it increased by 15 a.u. and in the fourth month it increased by 30 a.u. Staff skin hydration levels increased linearly over time. After 5 parameters enabling 55 a.u. And after 6 a.m., another one until 6 a.u. During and after radiotherapy, the subjects’ skin was hypersensitive, itchy and prone to cracking. The hydrolipid barrier weakened and the body was unable to protect itself against the consequences [8]. To prevent the occurrence of a disease state as a result of treatment, moisturizing preparations should be used. Studies have shown that collagen, which is a component of the tested preparation as well as endogenous collagen released from skin tissues, may exert a detrimental effect on its structure due to its molecular properties. A long-term state of oxidative stress induced by radiation therapy leads to dysfunction in the function and formation of collagen. The form that does not undergo chemical degradation is native collagen. Collagen is obtained from fish skins, which are by-products of the fish processing industry. Such utilization of raw materials promotes sustainable resource management and represents an environmentally friendly solution. Collagen is obtained from marine resources that do not have an allergenic potential, due to its molecular content and biocompatibility with human collagen. The effect of the skin regeneration process after radiotherapy on its structure and barrier functions was analyzed. Moreover, it is water-soluble and biodegradable; furthermore it increases the resistance of skin cells to environmental factors, including radiation. Hexapeptide-11 Peptide Encapsulated in Yeast (INCI: Saccharomyces Cerevisiae (Yeast Hulls)/Hexapeptide-11 Ferment Lysate) is especially beneficial for the condition of the skin. Research results suggest that this compound improves skin hydration by stimulating the production of glycosaminoglycans and collagen, which are responsible for the proper hydration of the deeper layers of the skin. On the surface of the epidermis, they create an impenetrable filter for evaporating water. The hydrophobic active substance penetrates deep into the epidermis, thus replenishing the lipids in the protective layer. Consequently, the emulsion increases the skin’s moisturizing parameter [8–10]. Pectins from upcycling apple pomace (INCI: Pyrus Malus Fruit Extract/Pectin) obtained from juice production contain antioxidants that help protect the skin. Pectins support the skin through their moisturizing properties. They act as a moisture-binding agent, which helps maintain the appropriate level of hydration.

Transepidermal water loss level from the epidermis (TEWL)

Figure 2 shows the average variation in the TEWL parameter. The results of the epidermal TEWL level were interpreted based on the Table 2.

Table 2

Interpretation of epidermal TEWL measurement results

| Interpretation of the results | Value TEWL [g/m2/h] |

|---|---|

| Very healthy skin | 0–10 |

| Healthy skin | 10–15 |

| Normal skin | 15–25 |

| Leather in poor condition | 25–30 |

| The skin is in critical condition | > 30 |

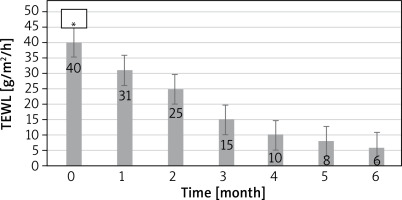

Figure 2

Change in the TEWL level of the patients’ skin after the first use of the preparation and during its use after radiotherapy. **p < 0.01 – significant increase from month 1 to 6 (W6) based on the post-hoc test. Group size test (n = 50)

The ability of the stratum corneum to retain water is important as it indirectly regulates skin hydration and indicates whether the hydro-lipid barrier is functioning properly. The dermis contains 80% water, while the stratum corneum contains only 13%. The average TEWL value measured in participants after radiotherapy was 40 g/m2/h. During the study, the TEWL parameter gradually improved, oscillating after 6 months of study at an average level of 6 g/m2/h (Figure 2). Regular use of the preparation, which contained flax extract (INCI: Linum Usitatissimum Seed Extract) rich in fatty acids, vitamins and minerals, as well as a-linolenic acid, has a moisturizing effect and supports the condition of the skin. This ingredient supports the occlusive effect of fatty raw materials and the physicochemical effect on intercellular cement. Lipids are incorporated into cement structures, which allows the properties of the epidermal barrier to change. Free radicals oxidize fatty acids that make up cell membranes and the hydrolipid coat of the skin (lipid peroxidation) and damage structural proteins, among others, collagen and enzymatic proteins (aggregation and denaturation process) [11]. Lipid peroxidation involves the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, resulting in the formation of fatty acid peroxides, which, like reactive oxygen species, are characterized by very high chemical reactivity. As a result, excessive water loss may be observed, which is inextricably linked to the dry skin that occurs during and after radiotherapy. In summary, the TEWL value improved after application of the product, also thanks to the phenomenon of merging irregular epidermal cells [12, 13].

pH parameter value

The normal reaction of human skin is acidic, ranging between 4 and 6 in the outermost layers of the skin. The dermis has a pH value of approximately 7. The slightly acidic pH on the skin has a bacteriostatic effect, prevents excessive colonization of pathogenic bacteria and facilitates the proper course of the skin cell exfoliation process. The hydrolipid coat, sebaceous gland secretions and NMF are responsible for maintaining the appropriate pH level of the skin. Many external factors can affect the pH level, such factors include too aggressive detergents, UV radiation, weather conditions, inadequate skin care, lack of a balanced diet. Each of these factors affects the deficiency of the ingredients that make up the hydrolipid coat and the natural moisturizing factor.

The average change in pH value before laminate application and after 1–6 months is presented in Figure 3. X-ray therapy also has an adverse effect on the condition of the skin, increasing the normal slightly acidic reaction on the skin surface. Based on the research, it was found that the longer the time since the end of the therapy, the less alkaline the pH became (Figure 3).

In order to accelerate the return of the appropriate pH reaction and thus the ability to perform protective functions, during the study the subjects were advised not to wash their skin with aggressive detergents, which also contributes to many irritations, excessive evaporation of water from the skin layers and increased sensitivity to external factors. To speed up the process of restoring the appropriate pH value after therapy, the preparation contains gluconolactone (INCI: Gluconolactone), panthenol and citric acid (INCI: Citric Acid). In addition to their pH-restoring properties, these compounds also have soothing and moisturizing properties. They have a soothing effect on irritations. Panthenol (INCI: Panthenol), which is another ingredient of the cosmetic formula tested in our study, accelerates healing, soothes irritations, burns and allergies [14–16].

Conclusions

It was confirmed that the product tested for an oncological patient has an appropriate level of skin hydration, supports the reconstruction of the skin and its energy barrier by reducing transepidermal water loss and restoring appropriate pH values. This approach facilitates the removal of the sequelae of pathological changes and expedites their resolution. For the emulsion to be more effective in patients exposed to ionized effects, it should be used long-term.

After interviewing the test subjects about their sensory and application experiences, moisturization occurred and the wound healing process was accelerated. The respondents observed that regular use yielded better results. The entire group of test subjects agreed that the effect of the product was consistent with the manufacturer’s claims.

Maintaining balance on the surface of the skin should be a priority, and then it can be used to prepare lubricating and moisturizing preparations.

The new modern methodology, based on obtaining fish skins from the fishing industry, is an innovative method due to the use of the upcycling approach. The formula of the test cosmetic is used to remove CO2 emissions. They give them a second life [17, 18]. This represents an upcycling approach to the development of future solutions that combine the provision of utility functions with the additional benefit of gaining access to active ingredients.