Introduction

Airborne/Inhalant and food allergy is affecting an increasing number of patients. Risk factors for sensitization, markers of disease severity and ways to prevent allergies are being sought. The role of the gastrointestinal microbiota in the development of allergies is an interesting issue. In the past, studies had been conducted on the gastrointestinal flora of the pregnant woman and its impact on the development of allergies in the childhood [1]. An interesting question is the possibility of influencing the natural course of an allergy that has already occurred in the patient [2]. A relevant question is whether alterations in the small-intestinal microbiota – including small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) – influence the phenotype and severity of allergic disease. This, in turn, raises the practical issue of SIBO testing in allergic patients. Routine testing in all patients is not recommended; rather, it may be considered when compatible gastrointestinal symptoms or risk factors are present. Meanwhile, the prevalence of food intolerances appears to be rising in high-income countries, and unbalanced diet, stress, and lifestyle factors are recognized contributors to microbiota disturbances [3–5].

Dysbiosis denotes an imbalance and disruption in the composition and function of the intestinal microbiota. Substantial evidence links dysbiosis with gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic disease, autoimmune conditions, and allergies. In allergy, microbial imbalance is proposed as a trigger and amplifier of symptoms through its effects on dysregulated immune responses [6–9].

Previous studies in both animal models and humans have demonstrated an association between increased intestinal permeability and the onset of food allergies. Impaired intestinal barrier function allows allergenic substances –such as food proteins, toxins, and microbial byproducts – to penetrate the intestinal lining due to compromised barrier integrity. Once these molecules enter the body, they can interact with immune cells in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), potentially activating immune responses and triggering allergic reactions [10, 11].

The gut microbiota plays a critical role in the complex mechanisms of allergic sensitization. In their 2020 review, Łoś-Rycharska et al. emphasized that reduced microbial diversity, along with an increased proportion of Enterobacteriaceae and Bacteroidaceae, is associated with a higher risk of food sensitization in children – particularly those born via caesarean section. The absence of exposure to maternal vaginal microflora at birth may predispose these children to allergic diseases due to colonization by potentially pathogenic microbiota acquired during delivery [12].

Additionally, bacterial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) play a key role in immune regulation. SCFAs, the primary products of bacterial fermentation, are mainly produced by Firmicutes bacteria, with butyrate and propionate being the most functionally significant. These molecules exhibit anti-inflammatory properties, enhance intestinal epithelial barrier integrity, and reduce the risk of food allergies [8, 13].

A study by Azad et al. involving 166 infants found that gut microbiota richness, rather than diversity, was statistically significantly lower at 3 months of age in children with food allergies compared to non-allergic controls. Furthermore, each quartile increase in microbiota richness during this period was associated with a 55% reduction in the risk of food allergy at 1 year of age. Conversely, each quartile increase in the Enterobacteriaceae/Bacteroidaceae ratio correlated with a twofold increase in allergy risk. These findings support the hypothesis that individuals with an imbalanced and less diverse gut microbiota are more susceptible to allergies. Such studies highlight the need for further research on the relationship between dysbiosis and allergies, particularly in the adult population [5, 6].

Despite the growing recognition of the role of gut microbiota in allergic diseases, few studies have explored the involvement of small intestinal dysbiosis –particularly small intestinal bacterial overgrowth – in allergy pathogenesis in adults. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) in patients with diagnosed allergic diseases and to assess potential associations between SIBO and allergy burden.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to specifically evaluate the occurrence of SIBO among patients with various allergic conditions, providing preliminary clinical data on a potential link that has thus far been underexplored. Given that SIBO is not routinely assessed in allergic patients, identifying its prevalence may have diagnostic and therapeutic implications and contribute to a better understanding of the gut–immune axis in allergy.

Material and methods

The study population consisted of patients evaluated for suspected food hypersensitivity of various origin at the Department of Allergology, Clinical Immunology, and Internal Medicine, encompassing both the inpatient ward and outpatient clinic. All participants reported adverse symptoms following the consumption of different food types but did not have a prior diagnosis of food allergy or SIBO before enrolment. The reported symptoms varied widely, ranging from cutaneous manifestations and gastrointestinal complaints to episodes of severe anaphylaxis.

None of the patients were following an elimination diet or a vegetarian/vegan diet at the time of evaluation. A detailed medical history was obtained from each participant, including documentation of hypersensitivity symptoms, chronic comorbidities, and current medications. This was followed by a comprehensive physical examination.

Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of celiac disease, known autoimmune or malignant disorders, or were receiving medications that could potentially confound the study results. Additional exclusion criteria included a prior confirmed diagnosis of food hypersensitivity, a history of allergen-specific immunotherapy, recent endoscopic procedures or abdominal surgery, current exacerbation of chronic disease, or the presence of an acute infection.

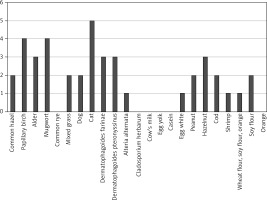

In this study, skin prick testing (SPT) was used as the primary method for evaluating allergic sensitization, in accordance with standard clinical practice. SPT is a well-established, cost-effective, and rapid diagnostic tool with high sensitivity for detecting IgE-mediated allergic reactions, particularly in patients with a clear history of immediate-type hypersensitivity symptoms. It enables the simultaneous assessment of multiple allergens and is routinely employed in both outpatient and inpatient allergology settings. Given the exploratory nature of this study and its focus on identifying possible associations between clinical allergy and SIBO, SPT was considered an appropriate and practical diagnostic approach at this stage. Serum-specific IgE (sIgE) testing was not included in this preliminary analysis due to its higher cost, limited immediate availability in routine diagnostics, and the absence of a clear indication for additional serological testing in all patients. In all participants, SPT was performed using a standardized panel of inhalant and food allergens from Diather’s allergen kit, including common hazel, papillary birch, alder, mugwort, common rye, mixed grass, dog, cat, Dermatophagoides farinae, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Alternaria alternata, Cladosporium herbarum, cow’s milk, egg yolk, casein, egg white, peanut, hazelnut, cod, shrimp, wheat flour, soy flour, and orange.

Available medical records were analysed to establish the diagnosis of atopic disease. A respiratory test for small intestine bacterial overgrowth with a load of 10 g lactulose was then performed using a Gastro+ Gastrolyzer device. Measurements were taken every 20 min, with a total of 10 measurements. An increase in the concentration of hydrogen in the exhaled air above 20 ppm was considered a positive result, according to the recommendations of the North American Breath Testing Consensus [5].

Statistical analysis

The obtained results were subjected to statistical analysis using MS Excel 360 and Statistica 13.1. Due to the relatively small sample sizes, the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of the data. The results (p < 0.05 for all variables) indicated significant deviations from a normal distribution. Consequently, non-parametric methods were applied, and group comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

A total of 44 patients were enrolled in the study, comprising 26 women and 18 men. All participants exhibited symptoms potentially indicative of food hypersensitivity of various aetiologies, including reactions associated with specific food consumption, abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting, skin changes, altered bowel movements, respiratory symptoms, and, in some cases, anaphylactic reactions.

Based on a comprehensive allergological history and the results of skin prick tests, patients were classified into two groups: those with a confirmed allergy (defined by the presence of allergy-suggestive symptoms and a positive skin test for at least one allergen) and those without a diagnosed allergy (defined by negative skin prick test results for the assessed allergens and a history suggesting hypersensitivity of non-allergic origin).

The characteristics of both groups, with and without a confirmed allergy, are presented in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups.

Table 1

Characteristics of patients with and without a diagnosis of allergy

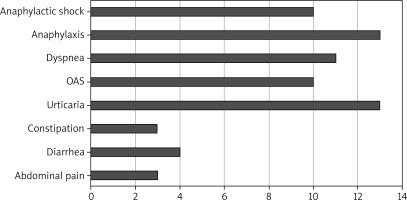

Positive SPT results are presented in Figure 1, with the most frequent sensitizations observed to cat and birch allergens. In patients with allergic disease, the course of the condition was evaluated in relation to the most common symptoms. The findings of this analysis are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Most common symptoms of allergic disease in the study population (number of patients reporting the symptom)

In patients diagnosed with food hypersensitivity other than allergy, abdominal pain (12), diarrhoea (8), constipation (5) and urticaria (1) predominated. In all patients, a breath test was performed after loading with lactulose. The results of the breath test are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Respiratory test results in patients with and without a food allergy diagnosis

A high proportion of positive breath test results was observed among patients both with and without confirmed food allergy. In the overall cohort evaluated for suspected food hypersensitivity, SIBO was diagnosed in 36 out of 44 (81.8%) patients. Notably, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of SIBO between patients with confirmed food allergy and those without. Similarly, no association was found between SIBO and positive SPT results to specific allergens; however, the limited sample size may have impacted the statistical power to detect such differences.

Although no statistically significant differences were found between the groups with and without confirmed allergy, several noteworthy observations emerged. The prevalence of SIBO was high in both groups – 85.7% in allergic patients and 78.3% in non-allergic patients – indicating that small intestinal dysbiosis may be common among individuals with food-related complaints, regardless of allergic status. However, the statistical comparison did not reveal a meaningful distinction between groups. Additionally, hydrogen concentration dynamics after lactulose ingestion, including baseline levels, peak values, and overall change, were comparable across both groups. The lack of significant findings may be attributed to the considerable clinical heterogeneity of the study population. Although all participants met the inclusion criteria of suspected food hypersensitivity, the final cohort encompassed a wide range of symptom presentations and underlying mechanisms – from IgE-mediated allergy to non-allergic food intolerance and functional gastrointestinal disorders. This variability likely diluted potential associations between allergic sensitization and SIBO. Moreover, the modest sample size limited the power of the study to detect subtle but potentially relevant differences. These preliminary findings underscore the need for future studies with larger, more phenotypically uniform populations and stricter inclusion criteria to more precisely assess the relationship between SIBO and allergic disease.

Discussion

SIBO is a well-documented cause of chronic abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and constipation. Allergic diseases contribute to low-grade inflammation, which can exacerbate gastrointestinal disorders. Food allergies may present as gastrointestinal symptoms, making the identification of their underlying cause challenging.

In 2019, Peña-Vélez et al. published a study analysing 70 children (aged 2–18 years) with chronic abdominal pain and diagnosed allergic diseases. The retrospective observational analysis, conducted between March and November 2018, assessed patients with chronic abdominal pain (CAP) using the lactulose hydrogen breath test (LHBT) to diagnose SIBO. Allergy evaluation was performed using skin prick testing or specific IgE determination, depending on the clinical presentation. SIBO was diagnosed in 35 patients, with 71.4% of them also having an allergic disease, compared to 28.6% of children without SIBO (p = 0.001). The odds ratio for any type of allergy in patients with SIBO was 5.45 (95% CI: 1.96–15.17; p = 0.001) [1]. A key hypothesis underlying this correlation suggests that chronic inflammation is a common feature in patients with allergic diseases [5].

In 2024, Huang et al. published an analysis of 159 children with atopic dermatitis (AD), dividing them into two groups: those with and without food allergies. Additionally, 100 children without diagnosed AD were included as a control group. The study evaluated eosinophil counts, total serum IgE levels, concentrations of food allergen-specific IgE using quantitative immunofluorescence testing, and selected serum cytokine levels. Stool samples were analysed for intestinal microbiota composition using metagenomic sequencing. The study found that eosinophil counts and the levels of IgE, IL-2, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, IL-12P70, and IFN-α were elevated in children with AD compared to controls. Furthermore, children with both food allergies and AD had lower levels of Lactococcus lactis (L. lactis) than those without food allergies, and improvements in gut microbiota were associated with reduced skin lesions [2].

These findings suggest a significant risk of gut microbiota dysbiosis in children with food allergies, highlighting the need for further research into microbiota disruptions and their impact on allergy symptoms. In SIBO, the small intestine becomes colonized by an excessive number of bacteria – such as Escherichia, Shigella, Pseudomonas, Aeromonas, Klebsiella, and Proteus – normally found in the colon, leading to dysbiosis and potential gastrointestinal symptoms.

In the present study conducted on adults, a positive breath test was observed in 85.7% of patients diagnosed with food or inhalant/airborne allergies and in 78.3% of those without such diagnoses. The high prevalence of positive breath test results in the study population, particularly among individuals with allergies, is noteworthy. However, due to the limited sample size, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn, underscoring the need for further research to obtain statistically significant results.

Rachid et al. have reported an increasing prevlence of food allergies, which they attribute to disruptions in the intestinal microbiota. They emphasize that maintaining eubiosis plays a crucial role in promoting oral tolerance as a balanced microbiota supports immune tolerance to various nutrients [3].

Studies in mouse models have demonstrated that gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), including Peyer’s patches, is underdeveloped in germ-free mice lacking exposure to pathogens. Interestingly, pathogen exposure in neonatal mice was found to promote GALT development and stimulate immune tolerance induction. This observation raises the possibility of strategies to reduce the risk of food allergy development in susceptible individuals [6].

The literature highlights a significant relationship between commensal microbiota and immune responses in allergic conditions, with modulation by innate lymphoid cells. Previous studies have shown that infants with cow’s milk protein allergy exhibit predominant dysbiosis, characterized by an increase in anaerobic bacteria. However, three European cohort studies analysing infants up to 18 months of age did not identify a significant correlation between dysbiosis and allergic sensitization [3, 6, 7].

During the early stages of life, the intestinal microbiota undergoes a dynamic and complex differentiation process. This critical period of microbiota development plays a fundamental role in shaping the human immune system and has long-term implications for overall health. Numerous scientific studies confirm the essential role of the microbiota in immune system development and regulation. There is strong evidence suggesting that low microbial diversity in early life may contribute to the onset and exacerbation of immune-mediated diseases [10, 14].

Diet is a key determinant of gut microbiota composition, significantly influencing immune function. An essential component regulating allergic responses is the immune barrier, which consists of the GALT, a part of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). GALT includes Peyer’s patches, intraepithelial lymphocytes, and lamina propria lymphocytes, which interact with the non-immune barrier system to protect the gastrointestinal mucosa from the translocation of food allergens into the bloodstream.

Dysbiosis, defined as an imbalance in the composition and function of the intestinal microbiota, can impair GALT function, leading to a disruption in immune tolerance mechanisms mediated by secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) and T lymphocytes. This, in turn, increases the risk of allergic reactions. Therefore, maintaining a well-balanced diet that supports microbiota function and gastrointestinal health is crucial [15–19].

A diet rich in soluble and insoluble fibre – found in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds – promotes the growth of beneficial gut microbiota. Conversely, diets based on the Western dietary model, which rely heavily on processed foods, saturated fats, and excessive sugar, can lead to dysbiosis. Such dietary patterns promote the proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms, potentially inducing inflammation and exacerbating allergic symptoms. Therefore, a key aspect of health prevention is maintaining a balanced diet that includes both digestible and non-digestible carbohydrates.

Among dietary components, resistant oligosaccharides – such as fructooligosaccharides (FOS), galactooligosaccharides (GOS), xylooligosaccharides (XOS), and inulin – play a critical role in sustaining a healthy microbiota. These oligosaccharides serve as prebiotics, providing essential nutrients for beneficial gut bacteria. When fermented in the large intestine, they stimulate the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which serve as an energy source for colonocytes and exert numerous health benefits [10, 20–22].

SCFAs have been shown to possess anti-obesity, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, immunoregulatory, hepatoprotective, and anti-tumour properties. Intestinal bacteria use specialized enzymes to efficiently ferment dietary fibre, producing SCFAs such as acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4). These SCFAs account for 90–95% of the total short-chain fatty acids in the colon and play a pivotal role in maintaining epithelial barrier integrity and modulating immune function through interactions with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [10, 22–24].

Among SCFAs, butyrate is particularly significant for intestinal and metabolic health. It serves as a primary energy source for intestinal epithelial cells and plays a key role in immune system modulation. Butyrate interacts with GPCRs located on epithelial and immune cells, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs) and dendritic cells, promoting interleukin-18 (IL-18) production and enhancing immune tolerance to commensal bacteria. The regulation of butyrate metabolism is therefore closely linked to maintaining intestinal homeostasis, a crucial factor in reducing disease risk and preventing allergic responses [25, 26].

Conclusions

A pilot study conducted in patients with food hypersensitivity revealed a high prevalence of SIBO. However, no statistically significant differences were observed between patients diagnosed with food allergy and those with non-allergic food intolerance of various aetiologies. Importantly, the absence of statistical significance does not exclude a potential association. The primary limitations of the study included a relatively small sample size and broad inclusion criteria. Furthermore, the diagnosis of SIBO was based solely on lactulose hydrogen breath testing, without simultaneous measurement of methane levels, which may have led to underdiagnosis of methane-dominant SIBO phenotypes.

Although the study aimed to compare outcomes between allergic and non-allergic individuals, the inclusion of a healthy control group would have strengthened the findings. Additional research involving a larger cohort is warranted to more precisely determine the role of SIBO in the onset and progression of atopic diseases. This need is particularly critical in light of the limited existing literature on this topic, which predominantly focuses on paediatric populations. Expanding investigations to include a broader adult population with atopic disorders – while accounting for variables such as diet, lifestyle, and comorbidities – could yield valuable insights into the potential contribution of SIBO to the pathogenesis and natural history of allergic diseases. Future studies should analyse patients with food vs. inhalant/airborne allergy separately, particularly in relation to dietary impact and microbiota.