Introduction

Skin dryness, thinning, and wrinkling in postmenopausal women are related to hormonal changes that decrease oestrogen metabolism [1]. Aging skin problems prompted the search for chemical peels capable of mitigating pigmentary disorders, scars, and wrinkles, reducing the signs of chrono- and photo-aging, and stimulating skin renewal and rejuvenation [2–5]. Chemical peels owe their worldwide popularity as cosmetic procedures to their ability to improve skin appearance with minimal invasiveness [6]. However, despite their popularity, there are no RCTs examining their usefulness in aesthetic medicine.

Traditional trichloroacetic acid (TCA) peels are cytotoxic for cells because of their low pH, and their ability to exfoliate the skin depends on their concentration and the number of peel layers. Because post-peel skin usually needs several days to recover, new formulations of TCA-based chemical peels have been created and they are safer for the stratum corneum, regenerate the skin, cause fibroblasts to produce elastin, boost the skin stress response system (SSRS), and improve skin quality (its brightness, elasticity, and turgor) [7–10]. The peroxides they contain promote wound healing by inducing VEGF expression in keratinocytes and facilitating angiogenesis [11] and largely protect the epidermis and dermis from being damaged by TCA [12]. These characteristics and the fact that novel TCA peels do not cause frosting or other adverse side effects such as intense erythema and swelling of the epidermis post-peel, render them superior to traditional TCA chemical peels. Their manufacturers recommend rubbing in peel layers into cleansed skin until absorbed and, depending on the product, washing them off with water.

Despite reports [12–14] showing that novel TCA peels are efficacious as traditional medium-depth TCA peels, research evidence about the skin revitalising effect of TCA peels is lacking [15]. In particular, there is a paucity of randomised clinical trials on the results of TCA peels in postmenopausal women.

Therefore, this trial set out to assess the efficacy of a novel TCA peel as a facial anti-aging therapy for postmenopausal women by comparing pre- and post-intervention changes in skin hydration, sebum levels, skin elasticity, and skin aesthetics between postmenopausal women in the experimental group and the placebo group.

Material and methods

Study design

The study was conducted between November 2020 and December 2022 as a prospective, randomised, controlled, single-centre clinical trial to determine the ability of a novel TCA peel to improve the skin condition (hydration, sebum, and elasticity) and skin aesthetics in postmenopausal women. The participants were divided into an experimental group (EG) and a control group (CG) to receive a TCA peel and a placebo solution, respectively.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All participants were volunteers who responded to an invitation posted to social media and posters displayed in the cosmetology clinic, on the study venue’s notice boards, the principal investigator’s institution, etc. A physician (an aesthetic medicine practitioner) included them in the trial if they were aged 59–65 years and had Fitzpatrick skin type II–III.

Women were excluded from the study if they had medical conditions preventing the use of chemical peels, such as bacterial, viral, or fungal infections, or flare-ups of inflammatory dermatoses, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. A tendency for keloid scarring, the use of topical retinoids, TCA peels, or other exfoliating and rejuvenating treatments (other chemical peels, ablative fractional laser therapy, microneedling radiofrequency, or other microneedling procedures, etc.) within 6 months prior to the study also disqualified women from the study. The last group of disqualifiers included contraindications for chemical peels, allergies, malignancy, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, a history of mental illness, pregnancy and breastfeeding, unreasonable expectations regarding the intervention results, and uncertain availability for follow-up assessments. All enrolled women submitted their written consent to participate in the trial.

Patient information and randomisation to groups

Following enrolment, women were informed in writing about the protocol and purpose of the study as well as that they could withdraw from it at any time without giving a reason. They were also assured that all willing participants in the placebo group would be entitled to receive treatment with a TCA peel according to the same protocol after the intervention.

To randomise participants between the EG and the CG, 46 opaque envelopes and a corresponding number of paper slips marked with letters A (the EG) and B (the CG) were prepared. A person unrelated to the study put one slip in each envelope and then sealed and numbered them randomly from 1 to 46. The envelopes were delivered to the principal investigator, who opened them individually in the presence of each woman to assign her to one of the two groups.

Blinding

Blinding was applied to the participants, the enrolling physician, two cosmetic therapists (researcher 1 (R1) and researcher 2 (R2)), the specialists assessing treatment outcomes (the physician evaluating changes in skin aesthetics, the facial photography specialist, and the cosmetologist evaluating skin hydration, elasticity, and sebum levels), the database administrator, and the statistical data analyst.

To prevent the participants and the cosmetic therapists from finding out whether an active peel or a placebo (ultrasound gel) was used, they were delivered to the treatment room in identical vials made of dark glass by the principal investigator, who also filled them.

The ultrasound gel contained a mixture of demineralized water, sodium polyacrylate, and ethylparaben.

Treatments were performed at different times of the day so that the participants could not share their experiences. As the novel TCA peels are painless, participants’ sensations during treatments did not reveal their group assignment, either.

Intervention

The aesthetic physician advised participants on the study rules applying during the treatment sessions and the intervention period, including the 3-month follow-up. They were instructed to keep their eyes closed when the peel was being applied, avoid sunlight, UV radiation, refrain from using other exfoliants (including home peels) and use mild washing agents. Each participant was given two 50-ml tubes of SPF50+ post-treatment cream (Dives Med Global Protection SPF50+) for daily skincare. No changes were recommended regarding participants’ night skincare routines.

Treatments were performed free of charge for the participants, following the pertinent guidelines for chemical peels and the manufacturer’s instructions. Before the first session, women were tested for allergies by applying a small amount of the TCA peel behind their ears.

The novel peel (PQ Age Evolution®, Promoitalia, Italy) used in the study contained TCA 34% that eliminates discoloration and small scars, smooths the skin, reduces blackheads, and stimulates collagen synthesis; kojic acid 10% that has antibacterial and antifungal properties and combats discoloration; urea peroxide 5% with confirmed skin lightening action; and coenzyme Q10 5% known for its antioxidant properties.

To prepare participants for a peel, following the removal of their make-up or thorough cleansing of their facial skin, petroleum jelly was applied to protect the sensitive regions of the face (the corners of the eyes, eyebrows, and lips). Afterward, three layers of a TCA peel were massaged into the facial skin with upward movements (the content of 1 vial was divided into three layers applied to the chin, cheeks, nose, and forehead skin). Each layer was rinsed with water before a new layer was put on. After the third layer, the peel was washed off with water and sunscreen cream SPF 50+ was applied. Altogether, 4 treatment sessions were performed at 7-day intervals.

The placebo peel protocol used in the CG was the same, including the number and frequency of sessions.

Measures

The potential participants’ eligibility for the trial was evaluated by a certified aesthetic physician based on interviews about their health condition, the presence of chronic diseases, and the use of medications. Treatment results were evaluated at 3 time points using medical devices, facial skin photographs, and questionnaires.

Evaluation of skin hydration, elasticity, and sebum levels

Skin hydration, elasticity, and sebum changes were assessed at baseline, post-intervention, and at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups with the Multi Skin Test Center® MC750 B2 (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH, Cologne, Germany). The description of the device can be found in [16–18]. The device’s SkinCheckUp® software v. 1.1.3.5 shows the measurement results in arbitrarily accepted units. During measurements, participants were lying in a semi-Fowler’s position in a cosmetic bed, whose head was elevated to a 40–45-degree angle. Measurements were carried out for all participants on the same day and in the same room to prevent changes of ambient conditions from affecting measurement outcomes. Statistical analysis was performed on the averages of the left and right measurements.

Skin hydration was analysed using the Corneometer® CM825 probe (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH), which measures the stratum corneum water content to a depth of 20 nm. All measurements were performed by the same blinded person (PI) in an ambient temperature of 20–23°C and humidity of 50–60% to ensure their consistency and reliability. The probe was held vertically to the skin, which was protected from direct sunlight and artificial light. Before measurements, make-up was removed, or the skin was cleansed, and at least 10 min of acclimatization were allowed. The skin hydration ranges for the T-zone and the cheeks used by the Multi Skin Test Center® MC 750 have been defined taking account of a person’s age; for women aged 50–59 years, these are: 1–24: very dry, 25–35: slightly dry, and 36–99: sufficiently hydrated skin; the respective ranges for women aged ≥ 60 years are: 1–22: very dry; 23–33: slightly dry; and 34–99: sufficiently hydrated skin.

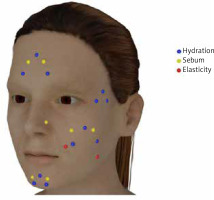

Skin hydration was measured at four sites (the cheeks, the corner of the eye (the crow’s feet area), the chin, and the forehead (Figure 1)), which were selected based on their reliability as a source of information about facial skin hydration. Cheek skin hydration was measured at three symmetrical points on the right and left cheek. The results were averaged and recorded as Cheek 1, Cheek 2, and Cheek 3. Skin hydration around the eyes was also measured at three symmetrical points selected near the left and right eye, and the averaged results were recorded as Eye 1, Eye 2, and Eye 3. The chin’s hydration was measured in the middle (Chin Middle) and at 2 symmetrical points on its sides; the latter measurements were averaged and recorded as Chin Side. Forehead skin hydration was also assessed at three points: the centre (Forehead Middle) and two symmetrical points on the right and left temples; the lateral measurements were averaged and recorded as Forehead Side.

Sebum levels in the T zone and cheek skin were measured with the Sebumeter® SM 815 (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH) under ambient conditions specified above by the same blinded person (PI). During measurements, which always started on the same side of the face, the device’s probe was held vertically to the skin. The Multi Skin Test Center® MC 750 uses facial sebum ranges defined with respect to age. For women aged 50–59, these are: 1–34: low level; 35–66: normal level; and 67–99: oily skin (the T-zone), and 1–24: low level; 25–55: normal level; and 56–99: oily skin (the cheek skin). For women aged ≥ 60, the respective ranges are 1–29: low level; 30–61: normal level; and 62–99: oily skin (the T-zone); and 1–22: low level; 23-53: normal level; and 54–99: oily skin (the cheek skin). Facial sebum was measured at two symmetrical points on the sides of the face: in the cheeks, the chin, the nose, and the forehead (Figure 1). The results were averaged and recorded as the cheek, chin, nose, and forehead points.

Skin elasticity assessments were performed using the Cutometer® 580 (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH); the method and conditions were the same as described above. On each cheek, two sites were measured: one lateral to the nasolabial fold (see Ohshima et al. [19]), approx. 3 cm from the ear (Cheek 1), and the other between the zygomatic bone and the mandibular angle (Cheek 2) (Figure 1), where the peel was rubbed upwards. The elasticity ranges of cheek skin used by the Multi Skin Test Center® MC 750 are: 1–37: low elasticity; 38–55: moderate elasticity; and 56–99: normal elasticity (women aged 50–59); and 1–19, 20–45, and 46–99, respectively (women aged ≥ 60).

Assessment of skin aesthetics

The appearance of participants’ facial skin was assessed using the Patient’s Aesthetic Improvement Scale (PAIS) and the Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS). Assessments with these scales were conducted pre- and post-intervention and after 1 and 3 months.

The PAIS is a self-completion tool with a 5-point scale, on which skin appearance can be rated as: 1 = worse; 2 = no change; 3 = somewhat improved; 4 = moderately improved; 5 = very much improved [20]. The participants filled in their PAIS based on their reflections in the mirror.

The GAIS were completed based on the sets of three photographs of participants’ faces taken during the three assessment sessions by the PI and Physicians 1 and 2. The GAIS is a validated 5-point relative improvement scale where: 1 = worse than before treatment; 2 = no change; 3 = minimal improvement; 4 = good improvement; and 5 = optimal improvement [20–22].

Photographs were taken with the Fujifilm XT-1 camera (22 mm lens) from a distance of 1.5 m without changing the settings. To ensure consistent light intensity, daylight was blacked out and three lamps – two flat panels GlareOne 20 BiColor and a light ring Nanlitehalo 18 – were used instead (1600 LUX and 6500 K as measured with the SEKONIC LITEMASTER PRO light meter, respectively). Participants were photographed in a sitting position, with the back and head touching the wall, after being instructed to keep a neutral facial expression and open eyes. All photographs were taken by the same specialists in the same part of the same room and under the same ambient conditions.

Monitoring for undesirable side effects

Participants could report any adverse effects related to treatments, particularly skin itching, burning, reddening, or rash, during sessions or by phone on other weekdays over the intervention period and the 3-month follow-up.

Primary study outcome

The primary study outcomes included skin hydration, elasticity, and sebum levels measured with the Multi Skin Test Center® MC 750 B2 device.

Secondary study outcomes

The secondary outcomes of the study were changes in facial skin appearance in the participants, assessed using the PAIS and GAIS.

Statistical analysis

Group size

To determine an appropriate group size for the trial, a pilot study with 10 women equally divided into the EG (TCA) and the CG (placebo) was carried out. The data collected in its course met the assumptions of two-way repeated measures ANOVA. The eta-squared obtained from the between-factor analysis for the effect on hydration was 0.18. With α = 0.05, test power = 0.9, the number of measurements = 6, the number of groups = 2, a correlation among the repeated measures = 0.53, and η2 = 0.15, the group size was estimated at a minimum of 40 participants, meaning that the experimental group and the control group should each comprise at least 20 participants. Because some participants could withdraw from the trial, each group size was increased to 23 participants, making a total of 46 participants. All calculations were performed using G*Power 3.1.9.7.

The decision to include 46 women in the trial was made after a trial with 40 participants was registered with the clinical database.

Intention-to-treat analysis

To retain the data of all randomly allocated women, an intention-to-treat analysis (ITTA) was performed. Data gaps were filled in using data obtained with the k-nearest neighbour technique [23].

Blinding effectiveness

Blinding effectiveness was determined based on the blinding questionnaires completed by the physician, therapists, and participants.

Statistical methods

The effect of the peel over time on skin elasticity, sebum levels, and hydration was evaluated by a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA). Its assumptions were verified and fulfilled; the continuous dependent variable was approximately normally distributed; there were no outliers in any of the repeated measurements; and the condition of sphericity was met. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were computed using Holm’s Sequential Bonferroni Procedure. The level of significance was set to α = 0.05. The PAIS and GAIS outcomes were analysed using the unpaired two-sample Wilcoxon test, and blinding effectiveness was tested by Fisher’s Exact Test.

All statistical analyses were performed using R 4.2.1 in the RStudio environment using the stats, lmerTest, afex, e1071, tidyverse, rstatix, and impute packages.

Results

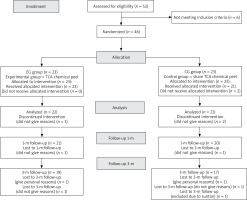

Fifty-two women were screened for the trial between September 30, 2021, and October 1, 2022, of whom 6 failed to meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 46 were equally and randomly divided into the experimental group (a TCA chemical peel) and the control group (a placebo). As 3 women (6.52%) withdrew from the trial before it ended (1 in the EG and 2 in the CG), its results were analysed for 43 participants (22 in the EG and 21 in the CG), with the lacking data being approximated as per the ITTA rules. Follow-up assessments at 1 month and 3 months were attended by 41 women (21 in the EG and 20 in the CG) and 37 women (19 in the EG and 18 in the CG), respectively. As before, the lacking data were approximated according to the ITTA rules. The flow chart of the study is presented in Figure 2.

Participants’ basic characteristics

The participants ranged in age between 57 and 65 years (64 ±2.61 years on average), and their body mass index (BMI) was between 19.72 and 32.79 kg/m2. Seventeen women (36.96%) had a normal BMI (18.5–24.99 kg/m2), 14 (30.43%) were overweight (25.0–29.99 kg/m2), and 13 (28.26%) had class 1 obesity (BMI 30.0–34.99 kg/m2). Seven (15.22%) women suffered from arterial hypertension, 5 (10.87%) from type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and 1 (2.17%) had rheumatoid arthritis. Two (4.35%) women were receiving hormone replacement therapy. All participants (100%) had skin type II according to the Fitzpatrick classification (Table 1). Facial skin assessments carried out with the Multi Skin Test Center MC 750 showed normal skin hydration (spots of slightly dry skin only occurred on the forehead and the cheeks), low sebum levels, and normal skin elasticity in all participants.

Table 1

Between-group homogeneity at baseline (n = 46)

| Variable | Experimental group (n = 23) | Control group (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|

| 1Age [years] | ||

| Mean ± SD | 60.74 ±2.34 | 60.52 ±2.93 |

| Median (lower quartile–upper quartile) | 60 (59–61.5) | 59 (59–64) |

| 2BMI [n (%) of women] | ||

| BMI 18.5–24.99 [kg/m2] | 10 (43.48%) | 9 (39.13%) |

| BMI 25–29.99 [kg/m2] | 8 (34.78%) | 6 (26.09%) |

| BMI 30–34.99 [kg/m2] | 5 (21.74%) | 8 (34.78%) |

| Comorbidities [n (%) of women] | ||

| Hypertension | 3 (13.04%) | 5 (21.74%) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 1 (4.35%) | 3 (13.04%) |

| Rheumatic diseases | 1 (4.35%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hormone replacement therapy [n (%) of women] | 2 (8.69%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fitzpatrick skin type [no./% of women] I/II/III/IV/V/VI | 0/23/0/0/0/0 0%/100%/0%/0%/0% | 0/23/0/0/0/0 0%/100%/0%/0%/0% |

At baseline, skin hydration at Cheek 3 was the only skin characteristic that statistically significantly differentiated the EG from the CG (it was significantly greater in the first group; p < 0.05; Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2

Between-group homogeneity at baseline, cont’d. (n = 46)

| Variable | Experimental group (n = 23) | Control group (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD Median (lower quartile–upper quartile) | ||

| 1Skin hydration [MSTC ranges2] | ||

| Cheek 1 | 33.17 ±9.42 30 (26.5–39.5) | 31.48 ±7.38 28 (26–36) |

| Cheek 2 | 30.43 ±8.13 30 (26–32) | 27.90 ±5.49 28 (24–30) |

| Cheek 3 | 45.91 ±8.19* 46 (42–50) | 40.67 ±8.39* 40 (34–45) |

| Eye 1 | 42.17 ±6.58 41 (38.5 – 44) | 39.43 ±6.63 39 (35–44) |

| Eye 2 | 43.00 ±7.51 40 (38–48) | 39.71 ±7.60 39 (34–46) |

| Eye 3 | 42.87 ±6.81 43 (39–47) | 38.90 ±6.98 40 (34–44) |

| Chin Side | 43.26 ±6.57 44 (38–49.5) | 40.76 ±6.56 41 (38–45) |

| Chin middle | 44.39 ±7.98 46 (40.5–50) | 41.71 ±7.99 41 (39–44) |

| Forehead side | 39.13 ±7.38 40 (34–42.5) | 37.05 ±8.04 38 (29–42) |

| Forehead middle | 38.96 ±8.93 38 (33.5–44.5) | 33.62 ±9.66 33 (26–42) |

| 1Skin sebum [MSTC ranges2] | ||

| Cheek | 3.74 ±2.49 3 (2–4) | 5.71 ±4.78 4 (3–6) |

| Chin | 3.87 ±2.03 4 (2–5) | 5.71 ±4.51 4 (3–6) |

| Forehead | 6.87 ±4.22 6 (3.5-9) | 7.19 ± 5.45 7 (4–10) |

| Nose | 8.43 ±7.60 5 (4–12) | 9.71 ±8.30 6 (4-12) |

| 1Skin elasticity [MSTC ranges2] | ||

| Cheek 1 | 69.43 ±10.00 71 (65–78) | 71.71 ±6.42 73 (65–77) |

| Cheek 2 | 68.09 ±8.39 70 (63–73) | 67.76 ±6.96 69 (64–74) |

Blinding effectiveness

The data in Table 3 show that the blinding procedure was effective. Neither the participants nor the trial staff (researcher 1, researcher 2, and the physician) were able to indicate at a statistically significant level the participants’ group assignments.

Table 3

Assessment of blinding effectiveness (n = 46)

Primary study outcomes (skin hydration, sebum, and elasticity)

Hydration

The statistically significantly greater skin hydration at Cheek 3 was the only skin characteristic to differentiate the EG from the CG at baseline (42.85 ±7.62 vs. 39.00 ±6.99; p < 0.05). Skin hydration levels measured at Cheek 1, Cheek 2, Eye 1, Eye 2, and Eye 3, Chin Side and Chin Middle, Forehead Side, and Forehead Middle were not statistically significantly different between the groups (p > 0.05). The post-intervention measurements showed that only Forehead Side had skin hydration statistically significantly greater in the EG than in the CG (38.91 ±8.20 vs. 35.00 ±7.53; p < 0.05). At all other points, difference was not significant (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4

Changes in skin hydration (n = 46)

| Group | MSTC ranges1 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± standard deviation Median (lower quartile–upper quartile) | ||||||||||||

| Cheek | Eye | Chin | Forehead | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Side | Middle | Side | Middle | |||

| Baseline | ||||||||||||

| EG | 33.09 ±9.45 30 (26.5–39.5) | 30.39 ±8.24 30 (26–32) | 45.85 ±8.19* 46 (42–50) | 42.2 ±6.49 41 (38.5–44) | 42.85 ±7.62 40 (38–48) | 42.85 ±6.81 43 (39–47) | 43.28 ±6.69 44 (38–49.5) | 44.39 ±7.98 46 (40.5–50) | 39.04 ±7.41 40 (34–42.5) | 38.96 ±8.93 38 (33.5–44.5) | ||

| CG | 31.5 ±7.39 28 (26–36) | 27.95 ±5.43 28 (24–30) | 40.71 ±8.52* 40 (34–45) | 39.43 ±6.68 39 (35–44) | 39.62 ±7.51 39 (34–46) | 39 ±6.99 40 (34–44) | 40.88 ±6.55 41 (38–45) | 41.71 ±7.99 41 (39–44) | 36.95 ±7.91 38 (29–42) | 33.62 ±9.66 33 (26–42) | ||

| Post-intervention | ||||||||||||

| EG | 27.83 ±6.52 27 (21.5–34) | 27.28 ±7.08 27 (21–32.5) | 36.89 ±10.66 34 (29–44.5) | 36.98 ±7.64 38 (34–43) | 35.83 ±7.88 34 (29.5–42.5) | 38.15 ±8.89 37 (31–46) | 43.76 ±6.88 46 (40–48) | 44.91 ±6.86 45 (42.5–50) | 38.91 ±8.2* 38 (34–46.5) | 36.96 ±8.62 39 (31.5–43) | ||

| CG | 28.31 ±8.21 26 (22–32) | 29.55 ±7.45 30 (24–36) | 40.4 ±7.16 40 (33–45) | 37.55 ±8.00 36 (32–44) | 38.12 ±7.28 38 (32–42) | 36 ±6.95 36 (30–40) | 43.79 ±5.22 44 (42–46) | 43.81 ±6.46 45 (36–48) | 35 ±7.53* 36 (30–39) | 34.33 ±8.82 36 (26–42) | ||

| 1-month follow-up | ||||||||||||

| EG | 35.9 ±6.46** 36 (31.5–39.5) | 32.72 ±6.58 32 (28–36) | 50.83 ±7.52* 50 (46.5–58.5) | 46.16 ±8.58 46 (40–51.5) | 46.85 ±8.44** 48 (43.5–51) | 45.52 ±7.45** 46 (40.5–52) | 48.19 ±4.75 48 (46–52) | 48.1 ±5.47 49 (45.5–51) | 44.55 ±8.93 46 (38.5–51) | 45.61 ±10.48* 45 (39–53) | ||

| CG | 30.5 ±5.87** 31 (26–35) | 30.01 ±6.05 30 (26–32) | 45.5 ±9.7* 42 (39–51) | 40.03 ±7.4 42 (36–45) | 40.5 ±6.13** 40 (37–45) | 38.92 ±6.76** 41 (34–44) | 44.43 ±5.67 46 (40–48) | 43.41 ±7.33 40 (39–49) | 39.28 ±6.81 40 (34–44) | 38.94 ±6.58* 39 (33–44) | ||

| 3-month follow-up | ||||||||||||

| EG | 41.98 ±9.06**** 41 (36.5–48.5) | 40.17 ±7.29*** 41 (34–46) | 52.79 ±7.92*** 54 (48–58.5) | 49.05 ±7.82** 51 (44–54) | 50.44 ±6.14**** 52 (46.5–55) | 50.07 ±7.29*** 51 (48–54) | 52.43 ±5.62*** 54 (50–55.5) | 52.28 ±7.54* 53 (47–57.5) | 49.66 ±6.33** 49 (46–54) | 52.41 ±8.22*** 54 (45.5–57) | ||

| CG | 31.03 ±6.86**** 30 (26–36) | 30.17 ±6.77*** 29 (26–33) | 42 ±6.8*** 42 (38–46) | 40.72 ±5.99** 41 (37–43) | 40.09 ±7.7**** 39 (34–44) | 39.62 ±7.54*** 42 (36–44) | 45.23 ±5.5*** 44 (42–48) | 45.04 ±6.66* 45 (42–50) | 41.53 ±7.72** 42 (38–46) | 40.68 ±8.68*** 40 (37–46) | ||

Skin hydration measured at 1-month follow-up was statistically significantly greater in the EG than in the CG at Cheek 1 (35.90 ±6.46 vs. 30.50 ±5.87; p < 0.01), Cheek 3 (50.83 ±7.52 vs. 45.50 ±9.70; p < 0.05), Eye 2 (46.85 ±8.44 vs. 40.50 ±6.13; p < 0.01), Eye 3 (45.52 ±7.45 vs. 38.92 ±6.76; p < 0.01), and Forehead Middle (45.61 ±10.48 vs. 38.94 ±6.58; p < 0.05). At 3-month follow-up, the EG had statistically significantly better skin hydration than the CG in all points, i.e., Cheek 1 (41.98 ±9.06 vs. 31.03 ±6.86; p < 0.0001), Cheek 2 (40.17 ±7.29 vs. 30.17 ±6.77; p < 0.001), Cheek 3 (52.79 ±7.92 vs. 42.00 ±6.80; p < 0.001), Eye 1 (49.05 ±7.82 vs. 40.72 ±5.99; p < 0.01), Eye 2 (50.44 ±6.14 vs. 40.09 ±7.70; p < 0.0001), Eye 3 (50.07 ±7.29 vs. 39.62 ±7.54; p < 0.001), Chin Side (52.43 ±5.62 vs. 45.23 ±5.50; p < 0.001), Chin Middle (52.28 ±7.54 vs. 45.04 ±6.66; p < 0.05), Forehead Side (49.66 ±6.33 vs. 41.53 ±7.72; p < 0.01), and Forehead Middle (52.41 ±8.22 vs. 40.68 ±8.68; p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Sebum

The baseline levels of skin sebum were not significantly different between the groups at any of the selected points (p > 0.05), but after the intervention and at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, they were significantly higher for the cheek skin in the CG than in the EG (6.33 ±5.72 vs. 3.41 ±2.35 (p < 0.05); 6.49 ±5.40 vs. 3.72 ±2.57 (p < 0.05); and 6.04 ±5.32 vs. 3.66 ±2.34 (p < 0.05), respectively). The forehead, nose, and chin skin sebum levels were not significantly different between the groups (p > 0.05; Table 5).

Table 5

Changes in the skin sebum level (n = 46)

| Group | MSTC ranges1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± standard deviation Median (lower quartile – upper quartile) | ||||

| Sebum | Forehead | Nose | Chin | Cheek |

| Baseline | ||||

| EG | 6.89 ±4.17 6 (3.5–9) | 8.46 ±7.59 5 (4–12) | 3.83 ±1.94 4 (2–5) | 3.76 ±2.51 3 (2–4) |

| CG | 7.12 ±5.52 7 (4–10) | 9.64 ±8.18 6 (4-12) | 5.69 ±4.49 4 (3–6) | 5.71 ±4.60 4 (3–6) |

| Post-intervention | ||||

| EG | 4.37 ±3.1 3 (2–6) | 4.39 ±3.64 4 (2–5) | 3.63 ±2.29 2 (2–4) | 3.41 ±2.35* 3 (2–4) |

| CG | 5.74 (3.81) 5 (2–8) | 7.07 ±4.51 6 (2–10) | 4.26 ±2.52 4 (2–5) | 6.33 ±5.72* 4 (2–6) |

| 1-month follow-up | ||||

| EG | 6.37 ±4.36 5 (2.5–10) | 6.69 ±5.57 4 (2.5–8) | 4.63 ±3.31 4 (2–6) | 3.72 ±2.57* 3 (2–4) |

| CG | 7.95 ±4.78 8 (5–10) | 8.39 ±5.44 6 (4–14) | 6.26 ±3.98 4 (4–8) | 6.49 ±5.4* 4 (4–7) |

| 3-month follow-up | ||||

| EG | 5.92 ±3.84 6 (3.5–7.5) | 8.05 ±7.52 5 (4–9) | 4.55 ±2.32 4 (2–6) | 3.66 ±2.34* 3 (2–4) |

| CG | 7.46 ±4.77 8 (4–10) | 8.41 ±5.57 6 (4–12) | 5.83 ±3.81 5 (4–8) | 6.04 ±5.32* 4 (3–6) |

Elasticity

The groups were not statistically significantly different in terms of skin elasticity (p > 0.05) at any of the assessment time points (Table 6).

Table 6

Changes in skin elasticity (n = 46)

| Group | MSTC ranges1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (standard deviation) Median (lower quartile–upper quartile) | ||

| Elasticity | Cheek | |

| 1 | 2 | |

| Baseline | ||

| EG | 69.46 (9.94) 71 (65–78) | 68.04 (8.27) 70 (63–73) |

| CG | 71.74 (6.48) 73 (65–77) | 67.79 (6.95) 69 (64–74) |

| Post-intervention | ||

| EG | 80.93 (6.4) 84 (76.5–85.5) | 77.39 (7.99) 78 (73–82) |

| CG | 77.29 (5.87) 77 (75–82) | 75.26 (6.23) 74 (72–80) |

| 1-month follow-up | ||

| EG | 77.16 (5.95) 76 (74–80.5) | 74.8 (9.22) 76 (70–81.5) |

| CG | 76.33 (4.66) 76 (74–80) | 72.59 (4.63) 72 (70–75) |

| 3-month follow-up | ||

| EG | 72.95 (7.02) 74 (69–77) | 68.9 (7.31) 68 (64.5–72.5) |

| CG | 70.85 (7.44) 70 (68–73) | 68.19 (5.09) 70 (64–72) |

Secondary study outcomes

Improvements in skin aesthetics

The EG consistently rated the improvement in skin appearance (PAIS) statistically significantly better than the CG, at an average of 4 at month 1 and 5 at month 3. In the CG, it was rated as 3 each time. Medians (lower quartile to upper quartile) calculated post-intervention were 4 (3 to 4.5) in the EG and 3 (3 to 4) in the CG (p < 0.05); those obtained at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups were 5 (4 to 5) vs. 3 (2 to 4) (p < 0.01) and 5 (3 to 5) vs. 3 (2 to 4) (p < 0.05) (Table 6).

Using the GAIS, the physician rated skin aesthetic improvement at 4 in the EG and 2 in the CG post-intervention and 1-month and 3-month follow-ups; each time, improvements in the EG were statistically significantly greater than in the other group. Medians (lower quartile to upper quartile) obtained post-intervention and at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups during the first assessment were 4 (3.5 to 5) in the EG, and 2 (2 to 2) in the CG (p < 0.0001 in all cases). In the repeated assessment, they were 4 (3 to 5) in the EG and 2 (2 to 3) in the CG (p < 0.001) post-intervention, 4 (2.5 to 4) in the EG and 2 (2 to 2) in the CG at 1-month follow-up (p < 0.0001), and 4 (2.5 to 4) in the EG and 2 (2 to 2) in the CG at 3-month follow-up (p < 0.0001) (Table 7). The weighted Cohen’s kappa was 0.82, pointing to very good inter-rater reliability of the physician’s assessments.

Table 7

Medians of PAIS and GAIS in the experimental and the control groups (n = 46)

| Assessment | Pre-intervention | 1 month post-intervention | 3 months post-intervention | Weighted Cohen’s kappa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAIS | |||||

| EG | 4 [3–4.5]* | 5 [4–5]** | 5 [3–5]* | ||

| CG | 3 [3–4]* | 3 [2–4] ** | 3 [2–4] * | ||

| GAIS | |||||

| Physician 1st assessment | Both physician’s measurements: 0.82 (almost perfect) | Physician versus PI assessment: 0.55 (moderate) | |||

| EG | 4 [3.5–5]**** | 4 [3.5–5]**** | 4 [3.5–5]**** | ||

| CG | 2 [2–2]**** | 2 [2–2]**** | 2 [2–2]**** | ||

| Physician 2nd assessment | |||||

| EG | 4 [3–5]*** | 4[2.5–4]**** | 3 [2.5–4]**** | ||

| CG | 2 [2–3]*** | 2 [2–2]**** | 2 [2–2]**** | ||

| Principal investigator (PI) assessment | |||||

| EG | 4 [3.5–4]**** | 4 [3.5–4]**** | 4 [3–4]**** | ||

| CG | 3 [2–3]**** | 3 [2–3]**** | 3 [2–3]**** | ||

EG – experimental group, CG – control group, PI – principal investigator, Pt – patient, PAIS – Patient’s Aesthetic Improvement Scale; interpretation of PAIS scores: 1 – worse (Pt unsatisfied), 2 – no change (Pt neutral), 3 – somewhat improved (Pt rather satisfied), 4 – moderately improved (Pt satisfied), 5 – very much improved (Pt very satisfied); GAIS – Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale; interpretation of GAIS scores: 1 – worse than before treatment, 2 – no change, 3 – minimal improvement, 4 – good improvement, 5 – optimal improvement; between–group effect – p-value:

Also using the GAIS, the PI rated improvements in skin aesthetics at 4 in the EG and 3 in the CG, both post-intervention and at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups; improvements were consistently significantly greater in the EG. Medians (lower quartile to upper quartile) calculated post-intervention and at 1-month follow-up were 4 (3.5 to 4) in the EG and 3 (2 to 3) in the CG (p < 0.001); at 3-month follow-up, they were 4 (3 to 4) in the EG and 3 (2 to 3) in the CG (p < 0.001) (Table 7). The weighted Cohen’s kappa of 0.55 indicated moderate inter-rater reliability between the physician’s and the PI’s assessments.

Discussion

Primary study outcomes – skin hydration, sebum and elasticity

The primary study outcomes were skin hydration, elasticity, and sebum. Facial skin hydration measured pre-intervention was sufficient in 35 women (76.09%; 20 (86.96%) in the EG and 15 (65.22%) in the CG) and slightly decreased in 11 women (23.91%; 3 (13.04%) in the EG and 8 (34.78%) in the CG). TCA peels improved skin hydration in participants in the EG, with positive changes being particularly noticeable at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups. The only facial regions where skin hydration measured post-intervention was better in the EG than in the CG were the sides of the forehead. At 1-month follow-up, the EG women had better skin hydration at 2 points on the cheeks, Forehead Middle, and 2 points near the eyes, and at 3-month follow-up, in all facial points.

The baseline levels of sebum were low in 44 women (95.65%; 22 (95.65%) in the EG and 22 (95.65%) in the CG) and normal in 2 women (4.35%; 1 in the EG and 1 in the CG). Measurements performed post-intervention and at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups showed that the EG had statistically significantly lower sebum levels than the CG only in two of the three cheek points. The EG’s sebum levels in the forehead, chin, and nose regions did not decrease.

Facial skin elasticity did not change significantly in the EG either. It needs to be noted, however, that 44 women (95.65%; 21 (91.30%) in the EG and 23 (100%) in the CG) had normal skin elasticity at enrolment, and in 2, both in the EG, it was moderate (4.35%).

Secondary study outcome – skin appearance

Facial skin assessments performed by the participants, the physician, and the principal investigator post-intervention and at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups consistently pointed to significantly better skin appearance in the women who received TCA peels.

Assessing their facial skin immediately post-intervention, the EG women rated its appearance as moderate but satisfying; after 1 and 3 months, they found the improvement to be substantial and very satisfying. In the CG, the outcomes of all three assessments pointed to a slightly improved and moderately satisfying appearance of the facial skin.

The physician did not observe changes in the overall appearance of the facial skin in the CG, but in the EG, its improvement was rated as good post-intervention and at 1-month follow-up. At 3-month follow-up, improvement ranged between minimal and good. All three assessments showed that skin appearance in the EG improved statistically significantly more than in the CG. The weighted Cohen’s kappa of 0.82 indicated very good inter-rater reliability between physician’s GAIS assessments [24].

The three assessments made by the PI pointed out that the improvement in skin appearance in the EG was ‘good’ and statistically significantly greater than in the CG, where it was minimal. According to the weighted Cohen’s kappa of 0.55, the inter-rater reliability between the physician’s and PI’s assessments was moderate.

The blinding tests showed that the participants, researchers and the physician were effectively blinded.

The results of the trial and other research findings

TCA chemical peels have long been used in cosmetology and aesthetic medicine to treat skin defects [4, 25]. Even so, Sitohang et al. [15] (who searched several scientific databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane and Scopus) for their recent systematic review on the efficacy of TCA peels as skin photoaging therapy found only 5 pertinent reports (Yildirim et al. [26], Holzer et al. [27], Artzi et al. [28], Kubiak et al. [29] and [30]). Their authors used ‘traditional’ TCA peels with TCA concentration between 15% and 35% as a single therapy or in conjunction with other cosmetic procedures.

Because of TCA’s keratolytic properties, its low concentrations dissolve and exfoliate the corneous layer of the epidermis, promoting cellular rejuvenation, and restoring normal skin functioning. However, TCA at concentrations above 15% can degrade the dermal proteins and produce adverse side effects such as stinging, burning, mild erythema and scaling, making patients restrict their activity until their skin recovers.

The increasing numbers of patients seeking facial treatments that are benign for the skin and do not interfere with regular activities prompted a search for new formulations of chemical peels [31, 32]. Cosmetic medicine also uses radiofrequency microneedling [28] and topical tretinoin therapy [26] which are as effective as traditional TCA peels while being less costly and better tolerated by patients.

The new formulations of chemical peels, which are designed around a modified TCA particle, regenerate skin without damaging it or causing discomforting sensations (tingling, burning and frosting involving a period of skin recovery post-treatment), in contrast with traditional peels [31–33]. The reformulated peel we selected for our study contained TCA 34%, urea peroxide 5%, coenzyme Q10 5%, and kojic acid 10%. Urea peroxide has lightening properties and a stabilising effect, coenzyme Q10 is an antioxidant, and kojic acid has antibacterial and antifungal properties in addition to reducing discoloration. According to the peel’s manufacturer, a TCA particle penetrates the epidermis without damaging it and activates in the dermis.

Having failed to find other studies with female participants and using peels of similar composition, we cannot compare our results with other authors’ finding. The most similar to our peel was the PRX-T33 TCA peel (TCA 33%, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and kojic acid 5%; GPQ Srl, Milano, Italy) used by Gold et al. [14] in their single-centre, open-label pilot study. Gold et al. argued that they chose the peel because its content of H2O2 makes TCA safer and less irritant for the epidermis and dermis. The study participants were five women with mild and moderate chrono- and photodamage of facial skin (Type II or III according to the Glogau Wrinkle Scale) aged from 49 to 72 years. Four treatment sessions were performed at weekly intervals. A session involved the application of four layers of the peel, one of which was rubbed in the eye lids, the nasolabial fold, glabella, and marionette wrinkles, and 3 in the other regions of the facial skin. The participants were instructed to use specialist post-peeling products (WiQoDrySkinCream and WiQoSmoothing Fluid, GPQ Srl; Milano, Italy) every day. The radiance, tone, smoothness, texture, redness, dryness, and overall appearance of participants’ facial skin were assessed at each session on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) Scale, and their tolerance for the peel was determined using the Investigator-Rated Tolerability Test (IRTT) and the Patient-Reported Tolerability Test (PRTT). Gold et al. [14] reported significant improvements in skin tone (p = 0.0174), smoothness (p = 0.0014), texture (p = 0.0017), redness (p = 0.0013), and overall appearance (p = 0.0073), but skin dryness, which was low at baseline, and radiance (p = 0.0749) did not change. After three sessions, all women rated skin smoothness, texture, and redness as better than before treatments. Notwithstanding its high concentration (TCA 33%), the peel did not cause skin frosting, epidermis exfoliation, or any other adverse side effects typically associated with TCA peels (oedema, tingling, burning, demarcation lines, discolorations, infections, or chronic erythema) in any of the participants. However, when interpreting the results, one needs to bear in mind that Gold et al.’s study [14] had a number of limitations, including a small group size, a large age span of the participants, a short follow-up period, and the lack of a control group and blinding. Our study is otherwise similar to it in terms of the peel composition, the treatment protocol, and having a physician and the PI evaluate changes in the appearance of facial skin.

Because of the lack of comparable studies, we could not make direct comparisons of changes in skin hydration, elasticity, and sebum level either. However, we verified and partially confirmed the assertion of the manufacturer of our peel (Promoitalia, Italy) that it is capable of regenerating, firming and lifting skin, improving its tone and hydration, and reducing sebum secretion after a series of treatments. Indeed, the peel proved effective in improving skin hydration and partially reduced skin sebum in our participants, but skin elasticity, which was normal pre-intervention in most of them, did not change.

We found only two studies that analysed skin hydration and elasticity in women after TCA peels. Both were authored by Kubiak et al. and were published in 2014 [29] and 2020 [30].

The first of them [29] compared a “traditional” peel based on TCA 15% with a peel containing glycolic acid 70% (GA), and the second one [30] compared changes in skin hydration and elasticity between women treated with peels containing GA 70% + TCA 15% and TCA 35%, respectively.

The earlier study involved 20 women aged between 41 and 60 years (a mean age of 54.2 ±3.8), showing signs of skin photoaging (types II and III according to the Glogau Wrinkle Scale). They were equally divided into two groups to receive peels containing TCA 15% and GA 70%, respectively, during 5 sessions performed 14 days apart. Treatment results were evaluated using the same Multi Probe Adapter MPA 5 (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH, Cologne, Germany) that we used. Skin elasticity and skin hydration were measured with the Cutometer SEM 474 and the Corneometer CM 820, respectively, in the corner of the eye (the crow’s feet area), the forehead, the cheeks, and the skin at baseline, after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks from the first treatment, and 3-month follow-up (20 weeks from the first treatment). Measurements at weeks 4, 6, 8, and 20 showed that skin elasticity and skin hydration improved statistically significantly (p < 0.05) in both groups, and that the differences between them were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). In neither group were severe side-effects of the peels, such as hyperpigmentation and discoloration, observed. The 70% GA group reported fewer discomforting sensations than the 15% TCA group (p < 0.05). These results led Kubiak et al. [29] to the conclusion that the peels were comparable regarding their ability to improve skin appearance. It is of note, however, that their study had some limitations, including a small sample size and the lack of randomisation, a control group, and blinding.

The subsequent study by the same authors recruited 40 women aged between 41 and 60 years (a mean age of 55.3 ±1.7 years), also with signs of photoaging (type II and III according to the Glogau Wrinkle Scale). The women were equally divided into an GA + 15% TCA group and a 35% TCA group. The study protocol provided for 5 peel treatments performed at 14-day intervals. In the first group, a 70% solution of glycolic acid was applied to participants’ facial skin for 4 min to prepare it for a peel and then was rinsed off with water. Then, a single layer of the peel was applied for 2–4 min. In the 35% TCA group, 2 peel layers were successively applied for 2 min and then were washed off with water and a 10% sodium bicarbonate solution. As before, skin elasticity was evaluated using the Multi Probe Adapter MPA 5 and the Cutometer SEM 474 and skin hydration with the Corneometer CM 820S. Measurements were made at baseline, after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks from the first treatment, and at 3-month follow-up (20 weeks after the first session). At week 2, skin elasticity in the 35% TCA group was 18.9% greater than in the GA + 15% TCA group, but the difference was not statistically significant. Starting with week 4, skin hydration was statistically significantly greater in the GA +15% TCA group (p < 0.05). Most women in both groups (89% in the GA + 15% TCA and 94% in the 35% TCA) rated the results of peels as good or very good; the between-group differences in ratings were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The GA + 15% TCA peel treatment was found more ‘skin-friendly’ than the TCA 35% peel because it only caused transient stinging and burning sensation; the TCA 35% peel was indicated as more discomforting and causing stronger stinging during application. Adverse effects of the peels were observed in both groups: 67% of the women in the GA + 15% TCA group and 93% in the 35% TCA group reported stinging and burning sensations, and 78% and 87% had mild erythema, respectively. The limitations of the Kubiak et al.’s study [30] included a small sample size and the lack of randomisation, a control group, and blinding.

The authors of the cited studies [27, 29, 30] reported that chemical peels containing TCA 15%, GA 70% + TCA 15%, and TCA 35% contribute to better skin elasticity and hydration in women at different ages, with the first two peels having fewer side effects and being better tolerated by patients. In our study, skin appearance evaluations made by specialists and participants consistently indicated that a chemical peel composed of TCA 34% stabilised with urea peroxide 5%, coenzyme Q10 5%, and kojic acid 10% can be safely and effectively used to treat facial skin defects in postmenopausal women. This conclusion is promising but more high-quality randomised clinical trials are needed to find out more about how the peel we used and similar peels influence the condition of facial skin in women at different ages, including its hydration, elasticity and sebum levels. Also, as the complexity of facial skin aging processes practically precludes the possibility of creating a single treatment or product addressing a variety of skin aesthetic issues in most patients [31–34], more clinical research with larger groups of participants and longer follow-up periods are needed to determine the effect of chemical peels used alone or in combination with other therapies vis-à-vis other peeling methods.

Monitoring for undesirable effects

During the PAIS interviews, women in both groups most frequently reported positive changes in the facial skin condition, such as improved skin hydration, smoothness, texture, a more even tone, and fewer fine wrinkles. The peel was very well tolerated as women in the EG only reported a few minor side effects and no severe side effects. After three treatments, one case of mild skin peeling and 1 case of benign erythema were recorded. In the control group, one woman found her skin to be drier after one week of using the post-treatment cream and replaced it with another one of similar composition. No other side effects were reported in the control group.

Novelty of the study, its advantages and limitations

Reliable scientific reports on the advantages and disadvantages of aesthetic treatments for women aged over 60 years are not available [35], let alone studies comparing the effects of TCA-based peels, especially between their standard and modern formulations. Our study appears to be the first randomised clinical trial investigating the efficacy of a novel TCA chemical peel as an anti-aging skin therapy for postmenopausal women. What makes it distinct from most studies cited in the paper is the use of a placebo group and the effective blinding of all participants and the staff. The fact that only a few participants dropped out of it and were lost to follow-up demonstrates the reliability of its results.

Our study also has several limitations, such as the failure of the Mexameter® device indicated in the registration form, which prevented the evaluation of participants’ skin for pigmentation, dyschromia, and erythema.

Also, we did not control whether participants used the post-treatment cream daily as recommended or verify their knowledge of skincare before the trial.

These limitations can be removed from future research by testing the participant’s knowledge of skincare at the enrolment stage, having them keep skincare diaries, and ensuring they follow the same night skincare routine. Also, recruiting women who did not have aesthetic treatments for several years before the study, analysing more skin parameters (pH, transepidermal water loss (TEWL), skin viscoelasticity, etc.), and deploying digital skin imaging applications could contribute to greater reliability of results. Finally, having controls and applying a TCA-based peel to them without rubbing it in could provide more insight into the peel’s influence on skin elasticity.

Our study has shown that a novel TCA chemical peel (TCA 34%, urea peroxide 5%, coenzyme Q10 5%, and kojic acid 10%) contributes to better skin hydration in postmenopausal women. Its ability to reduce skin sebum production was confirmed for one facial point only, so more randomised clinical trials are needed to verify it. Changes in skin elasticity were not observed, but in most women in both groups, it was in the normal range pre-intervention. Therefore, a more reliable evaluation of the effect of a novel TCA-based chemical peel on skin elasticity in postmenopausal women would require subjects with reduced facial skin elasticity. Overall, our study has demonstrated that a novel TCA peel can improve facial skin appearance in postmenopausal women.