Introduction

One of the most common form of food allergy, affecting 2–3% of the paediatric population, is cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) [1, 2]. In most patients, the disease has a mild course and usually resolves by the age of 3 to 4 years; however, in some cases, it can persist, and even pose a life-threatening risk by developing into anaphylaxis [3–8]. Patients with CMPA demonstrate a wide range of ambiguous and diverse symptoms, with varying onset times, after consuming cow’s milk. In addition, as diagnosing CMPA is further complicated by the presence of masked allergens, and the lack of simple, clear diagnostic tools [9], it is often both overdiagnosed and underdiagnosed [10]. Nevertheless, a proper diagnosis is a key factor influencing the social and economic life of children and their families [11, 12].

The diagnosis of IgE-mediated CMPA is based on various sources, including medical history, allergy assessment through skin prick tests (SPT) and/or allergen-specific IgE antibodies (asIgE), diagnostic elimination diet, and oral food challenge (OFC) [9, 13–20]. The medical history alone may sometimes be sufficient for diagnosis, but it must clearly indicate a link between symptoms typical of IgE-mediated food allergy and the consumption of milk or dairy within the previous 2 to 4 h [21]. SPT and/or asIgE assessment can only confirm sensitization, which alone is not indicative of a food allergy diagnosis. Moreover, the cut-off values determined in studies conducted outside Poland cannot be used in daily practice, as data from a specific population should not be transferred to other unstudied populations [22]. Finally, a diagnostic elimination diet may be an essential element of the diagnostic process but alone is not sufficient to confirm a diagnosis.

The most reliable diagnostic tool is OFC; however, it is time-consuming, costly, often difficult to implement, and, most importantly, can carry risks for the patient [9, 20, 23]. Therefore, new tools are continuously being sought to improve the diagnosis of food allergies, including CMPA. Recent studies examined the potential of molecular-based diagnosis (component-resolved diagnostics; CRD) for CMPA, but with conflicting results.

Aim

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the potential of evaluating cow’s milk allergens using molecular methods for determining the acquisition of tolerance to cow’s milk in children with IgE-mediated allergy.

Material and methods

Initially, 50 children were qualified to take part in the study. All were hospitalized in the Paediatric, Allergology, and Gastroenterology Clinic and under the care of the Paediatric Allergy Outpatient Clinic at University Hospital No. 1 in Bydgoszcz (level III referral centre) from 2018 to 2021; however, ultimately, 49 children (mean age: 2 years and 8 months) were included. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age from 1 month to 18 years, sensitization to cow’s milk allergens (confirmed by the presence of asIgE > 0.35 kU/l, determined using the Polycheck method and/or a positive SPT result ≥ 3 mm), symptoms suggestive of IgE-mediated CMPA, and consent from parental/legal guardian for participation. The characteristics of the children involved in the study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the study group

The study was observational and prospective in nature. It was conducted in two phases: Phase I at the time of study inclusion, and Phase II after 12 months. At both time points, the analysis was performed based on medical history data, together with OFC and asIgE measurement for cow’s milk allergens by the Polycheck method. In addition, asIgE level was determined against cow’s milk extract, α-lactalbumin (α-LA), β-lactoglobulin (β-LG), casein, and bovine serum albumin (BSA), using the Fluoro-Enzymatic Immunoassay (FEIA) technique; the analysis was performed using an ImmunoCAP 100 analyzer and test kits (Phadia/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Sensitization was confirmed with asIgE > 0.35 kU/l (Polycheck) and/or asIgE ≥ 0.1 kU/l (Immuno-CAP). The FEIA tests were performed in the Immunology-Allergology Laboratory at the Clinic of Allergology, Clinical Immunology, and Internal Diseases SU of University Hospital No. 2 in Bydgoszcz.

To confirm or exclude CMPA and monitor tolerance, an open OFC was performed with baked cow’s milk (cow’s milk muffin according to the Jaffe Food Allergy Institute recipe [24]) and/or raw milk (lactose-free modified formula or pasteurized cow’s milk), according to the guidelines of the Polish Society of Allergology and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) [9, 20, 24–26]. The choice of the allergen was based on the patient’s current tolerance, as assessed from the medical history.

If the OFC with a baked allergen yielded a negative result, an OFC with raw milk was performed the following day. If an acute allergic reaction occurred, immediate treatment was administered, and the OFC was discontinued according to the criteria proposed by the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology [25, 27]. Anaphylaxis occurring during OFC was diagnosed according to the criteria proposed by EAACI [28], and its severity was classified according to the systemic reaction scoring system given by the World Allergy Organization (WAO) [29].

Statistical analysis

The data was subjected to statistical analysis using PS IMAGO PRO 7.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics 27) software and Python 3.8.10. The cut-off points for sIgE to cow’s milk and its proteins were determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

To determine high-risk markers for a positive OFC result with cow’s milk (both baked and raw), the best area under the ROC curve (AUC) values were used to calculate optimal cut-off points, i.e. those that best predicted the outcome of the OFC based on the obtained asIgE results. The optimal cut-off points were considered to be the asIgE concentrations with the highest accuracy (ACC), high sensitivity, specificity, and both high positive (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV).

Results

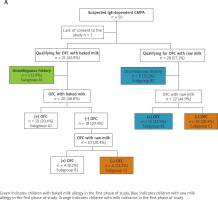

The present study reports only the results of the analyses of allergens measured using the FEIA method. In the first phase of the study, 49 children were divided into three subgroups based on medical history, confirmed sensitization, and OFC results:

Subgroup A1 (n = 11; 22.5%): children with an allergy to baked cow’s milk,

Subgroup B1 (n = 22; 45%): children with an allergy to raw cow’s milk,

Subgroup C1 (n = 16; 32.5%): children with full tolerance to cow’s milk.

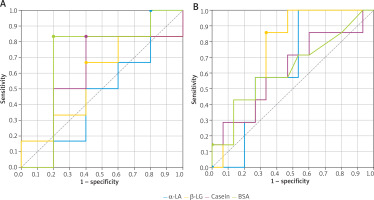

This classification was equivalent to identifying two phenotypes of CMPA: allergy to baked milk and allergy to raw milk. Anaphylaxis was diagnosed in 13 (39.4%) children with CMPA; of these, 6 (18.2%) children experienced anaphylaxis during the OFC with baked milk, and 7 (21.2%) during the OFC with raw milk. The systemic allergic reactions observed in the subgroups, classified according to the WAO 2020 guidelines [29], are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Classification of systemic allergic reactions according to WAO 2020 [29] observed during positive OFCs with cow’s milk in the examined children in phase I of the study

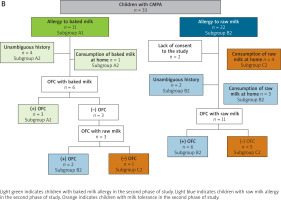

In the second phase of the study, 31 children from subgroups A1 and B1 were again subjected to the OFC. Two patients had withdrawn from the second phase of the study. Based on the findings, the following three subgroups were created:

Subgroup A2 (n = 8; 25.8%): Children with persistent allergy to baked cow’s milk,

Subgroup B2 (n = 13; 41.9%): Children with persistent allergy to raw cow’s milk,

Subgroup C2 (n = 10; 32.3%): Children without allergy.

The study flow diagrams are shown in Figure 2 A (for Phase I) and Figure 2 B (for Phase II).

Figure 2

A – Scheme for conducting oral food provocations with cow’s milk (baked and raw) in phase I of the study

Figure 2

B – Scheme for conducting oral food provocations/challenges with cow’s milk (baked and raw) in phase II of the study

The value of molecular testing in CMPA diagnosis

Predictors of positive OFC results with cow’s milk based on the assessment of asIgE measured using the FEIA method

Our findings indicate that the best predictor for diagnosing CMPA is the presence of asIgE levels for the cow’s milk extract ≥ 0.72 kU/l, with a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 18.8%, and accuracy of 73.5%; in addition, casein ≥ 0.41 kU/l is another good indicator, with a sensitivity of 87.9%, specificity of 50%, and accuracy of 75.5% (Table 2). In children with baked milk allergy (subgroup A1), the optimal cut-off point for asIgE for casein was found to be ≥ 7.01 kU/l (sensitivity = 63.6%; specificity = 93.8%; ACC = 81.5%; AUC = 0.869) (Table 2).

Table 2

Diagnostic efficacy of sIgE for extract and cow’s milk allergens determined by FEIA in the diagnosis of IgE-mediated CMA – ROC curves analysis

| Allergen, AUC | Cut-off* [kU/l] | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | ACC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgE-mediated CMA | ||||||

| Cow’s milk extract, AUC = 0.646 | 0.72a | 100 | 18.8 | 71.7 | 100 | 73.5 |

| 29.7b | 27.3 | 93.8 | 90 | 38.5 | 49 | |

| 37.2b | 18.2 | 100 | 100 | 37.2 | 44.9 | |

| α-LA, AUC = 0.670 | 0.57a | 72.7 | 50 | 75 | 47.1 | 65.3 |

| 8.03b | 39.4 | 93.8 | 92.9 | 42.9 | 57.1 | |

| 18.8b | 21.2 | 100 | 100 | 38.1 | 46.9 | |

| β-LG, AUC = 0.663 | 0.59a | 75.8 | 56.2 | 78.1 | 52.9 | 69.4 |

| 19.5b | 9.1 | 100 | 100 | 34.8 | 38.8 | |

| Casein, AUC = 0.763 | 0.41a | 87.9 | 50 | 78.4 | 66.7 | 75.5 |

| 5.96b | 42.4 | 93.8 | 93.3 | 44.1 | 59.2 | |

| 20.9b | 30.3 | 100 | 100 | 41 | 53.1 | |

| BSA, AUC = 0.620 | 0.1a | 54.5 | 68.8 | 78.3 | 42.3 | 59.2 |

| 3.2b | 18.2 | 100 | 100 | 37.2 | 44.9 | |

| IgE-mediated CMA to baked milk | ||||||

| Cow’s milk extract, AUC = 0.784 | 10a | 81.8 | 68.8 | 64.3 | 84.6 | 74.1 |

| 77.9b | 27.3 | 100 | 100 | 66.7 | 70.4 | |

| α-LA, AUC = 0.815 | 4.84a | 72.7 | 87.5 | 80.0 | 82.4 | 81.5 |

| 18.8b | 27.3 | 100 | 100 | 66.7 | 70.4 | |

| β-LG, AUC = 0.759 | 0.96a | 90.9 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 90.9 | 74.1 |

| 19.7b | 18.2 | 100 | 100 | 64 | 66.7 | |

| Casein, AUC = 0.869 | 7.01a | 63.6 | 93.8 | 87.5 | 78.9 | 81.5 |

| 29.8b | 45.5 | 100 | 100 | 72.7 | 77.8 | |

| BSA, AUC = 0.790 | 0.1a | 81.8 | 68.8 | 64.3 | 84.6 | 74.1 |

| 5.39b | 36.4 | 100 | 100 | 69.6 | 74.1 | |

| IgE-mediated CMA to fresh/raw milk | ||||||

| Cow’s milk extract, AUC = 0.577 | 0.72a | 100 | 18.8 | 62.9 | 100 | 65.8 |

| 37.2b | 13.6 | 100 | 100 | 45.7 | 50 | |

| α-LA, AUC = 0.598 | 8.03a | 31.8 | 93.8 | 87.5 | 50 | 57.9 |

| 20.1b | 18.2 | 100 | 100 | 47.1 | 52.6 | |

| β-LG, AUC = 0.615 | 0.59a | 68.2 | 56.2 | 68.2 | 56.2 | 63.2 |

| 19.5b | 4.5 | 100 | 100 | 43.2 | 44.7 | |

| Casein, AUC = 0.710 | 1.84a | 68.2 | 68.8 | 75 | 61.1 | 68.4 |

| 20.9b | 22.7 | 100 | 100 | 48.5 | 55.3 | |

| BSA, AUC = 0.536 | 0.49a | 27.3 | 87.5 | 75 | 46.7 | 52.6 |

| 3.2b | 9.1 | 100 | 100 | 44.4 | 47.4 | |

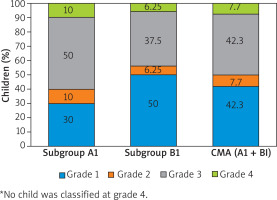

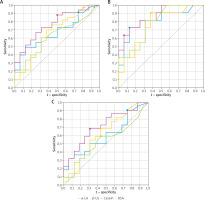

Children with a positive OFC result with raw milk (subgroup B1) demonstrated low AUC values; hence, the asIgE concentrations with 95% PPV showed low diagnostic value. The best predictor of raw milk allergy was asIgE for casein ≥ 1.84 kU/l (sensitivity 68.2%; specificity 68.8%; ACC = 68.4%; AUC = 0.710) (Table 2). Additionally, the children with raw milk allergy (subgroup B1) demonstrated similar asIgE values for α-LA (8.03 kU/l) and β-LG (19.5 kU/l), corresponding to 95% PPV, to those in subgroup A1 (8.34 kU/l and 19.7 kU/l, respectively). It was also found that the assessment of asIgE using the CRD method in CMPA diagnosis (A1 + B1) has low diagnostic value, i.e. with low AUC values (Table 2, Figures 3 A–C).

Figure 3

ROC curves for cow’s milk allergens (determined by the FEIA method), used to determine cut-off points enabling the diagnosis of cow’s milk allergy without oral challenge tests: A – in children with cow’s milk allergy (A1 + B1), B – in children with allergy to baked milk (A1), C – in children with allergy to raw milk (B1)

The value of molecular testing in assessing the risk of anaphylaxis during OFC with cow’s milk based on FEIA assessment of asIgE

To identify markers of potential anaphylaxis during the OFC with baked cow’s milk, optimal cut-off points for asIgE were determined. The points were calculated based on the ROC curves for individual milk allergens, measured using the FEIA method (Figures 4 A, B), and with the calculated ACC values (Table 3). The highest accuracy was noted for asIgE for casein at 7.01 kU/l (ACC = 72.7%), which also demonstrated 75% PPV at 30.9 kU/l. In addition, 100% PPV scores were noted for 44.8 kU/l asIgE for α-LA, 20.8 kU/l asIgE for β-LG, and 100 kU/l asIgE for milk extract. The best predictor of anaphylaxis in patients with raw milk allergy was asIgE for β-LG, at a concentration of at least 1.71 kU/l; this value demonstrated the highest AUC (0.724) among all allergens (i.e., β-LG, casein, BSA, and milk extract) with similar ACC (72.7%) (Table 3, Figures 4 A, B).

Table 3

High-risk markers of anaphylaxis in the oral food challenges with cow’s milk – determined by sIgE (FEIA)

| Allergen, AUC | Cut-off* [kU/l] | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | ACC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgE-mediated CMA to baked milk | ||||||

| Cow’s milk extract, AUC = 0.567 | 19a | 66.7 | 60 | 66.7 | 60 | 63.6 |

| 100b | 16.7 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 54.5 | |

| α-LA, AUC = 0.50 | 0.65a | 100 | 20 | 60 | 100 | 63.6 |

| 44.8b | 16.7 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 54.5 | |

| β-LG, AUC = 0.60 | 4.7a | 66.7 | 60 | 66.7 | 60 | 63.6 |

| 20.8b | 16.7 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 54.5 | |

| Casein, AUC = 0.60 | 7.01a | 83.3 | 60 | 71.4 | 75 | 72.7 |

| 30.9b | 50 | 80 | 75 | 57.1 | 63.6 | |

| BSA, AUC = 0.70 | 5.39ab | 50 | 80 | 75 | 57.1 | 63.6 |

| IgE-mediated CMA to fresh/raw milk | ||||||

| Cow’s milk extract, AUC = 0.619 | 37.2 | 28.6 | 93.3 | 66.7 | 73.7 | 72.7 |

| α-LA, AUC = 0.629 | 3.24a | 57.1 | 66.7 | 44.4 | 76.9 | 63.6 |

| 0.22ab | 100 | 46.7 | 46.7 | 100 | 63.6 | |

| β-LG, AUC = 0.724 | 1.71ab | 85.7 | 66.7 | 54.5 | 90.9 | 72.7 |

| Casein, AUC = 0.638 | 23.6a | 28.6 | 93.3 | 66.7 | 73.7 | 72.7 |

| 64.1ab | 14.3 | 100 | 100 | 71.4 | 72.7 | |

| BSA, AUC = 0.629 | 0.53 | 42.9 | 86.7 | 60 | 76.5 | 72.7 |

| 42.4 | 14.3 | 100 | 100 | 71.4 | 72.7 | |

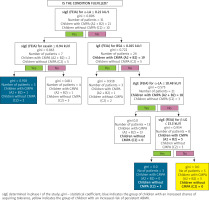

The utility of molecular testing in monitoring CMPA. Prognostic factors for persistent CMPA or acquiring natural tolerance

Phase I of the study used a classification tree model to evaluate the potential of asIgE for cow’s milk extract and allergens for monitoring the progression of CMPA, using the FEIA method. The following asIgE concentrations noted at the time of CMPA diagnosis (i.e. in Phase I of the study) were found to be prognostic factors for persistent CMPA in Phase II:

β-LG > 13.31 kU/l and α-LA > 10.48 kU/L (Figure 5), or

Figure 5

Classification tree for monitoring the course of CMPA using asIgE for cow’s milk allergens (FEIA)

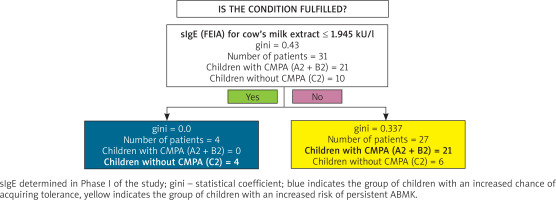

Cow’s milk extract > 1.95 kU/L (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Classification tree for monitoring the course of CMPA by sIgE for FEIA-labelled cow’s milk extract

The following asIgE concentrations at the time of CMPA diagnosis (i.e., in Phase I of the study) were found to promote the acquisition of tolerance to cow’s milk:

β-LG ≤ 13.30 kU/l (Figure 5), or

α-LA ≤ 0.22 kU/l and casein ≤ 0.94 kU/l (Figure 5), or

Cow’s milk extract ≤ 1.95 kU/l (Figure 6).

Discussion

Cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) is one of the most common food allergies in children, both in Poland and globally. While it typically has a mild course, some patients present with anaphylactic symptoms, which can be life threatening. Establishing a proper diagnosis is a priority for paediatric allergists, as it safeguards the patient from severe, life-threatening allergic reactions and minimizes the need for unnecessary elimination diets. Our findings present the concentrations of asIgE for cow’s milk allergens that can serve as indicators for diagnosing CMPA and for monitoring its course.

The value of molecular/FEIA testing in CMPA diagnosis

Previous studies [30, 31] have proposed asIgE for casein as the best predictor of CMPA. However, Castro et al. [32] found the optimal cut-off for asIgE for cow's milk extract to have better diagnostic value than asIgE for individual milk allergens (casein, α-LA, β-LG). These differences may arise from the varying median ages of the studied populations, i.e. ranging from 1.9 years [30], to 4.9 years [31], and even 7.6 years [32]. In the present study, the median age was 2.7 years; it was also shown that the presence of asIgE for casein is characteristic of persistent CMPA, making it more typical for older children.

In the present study, the best cut-off point for a positive OFC with baked milk was an asIgE for casein ≥ 7.01 kU/l, which demonstrated 63.6% sensitivity and 93.8% specificity. A study of 225 children with CMPA by Caubet et al. [30] found optimal asIgE values (UniCAP) for OFC with baked milk to be 20.2 kU/l for casein and 24.5 kU/l for cow's milk extract; these values yielded 95% specificity. Similarly, a study of 30 children with IgE-mediated CMPA by Kwan et al. [33] found 6 kU/l asIgE casein, measured by ImmunoCAP, to be the optimal indicator. In contrast, a cross-sectional study of over 200 children with suspected CMPA by Vilar et al. [34] demonstrated < 5 kU/l asIgE to cow's milk extract (ImmunoCAP) indicated an 80% chance of developing tolerance to baked milk, with a 50% chance at < 42 kU/l and a 20% chance at < 85 kU/l.

In the present study, the optimal decision point for predicting a positive OFC with raw milk was found to be an asIgE level of ≥ 1.84 kU/l for casein (ACC = 68.4%; PPV = 75%). In contrast, Vanto et al. [35] found cow's milk extract of 0.70 kU/l (UniCAP 100) to achieve 70% PPV and 88% specificity in a group of 180 infants with suspected CMPA; however, unlike the present study, their findings were based on a double-blind placebo-controlled provocation test. A prospective study of infants by Roehr et al. [36] found cow's milk extract of 50 kU/l to be optimal for predicting a positive OFC with raw milk using the FEIA method (100% PPV).

Petersen et al. [37] found the best predictors of clinical reactivity in raw milk allergy to be asIgE for cow's milk extract ≥ 3.64 kU/l and asIgE for casein ≥ 2.33 kU/l, measured by ImmunoCAP, with sensitivities of 63% and 61%, and specificities of 87% and 83%, respectively.

García-Ara et al. [38] examined the optimal values of asIgE for cow's milk extract and casein (CAP FEIA) for predicting OFC outcomes with raw milk. They found the best respective cut-off values, with sensitivities of around 70–90% and specificities of 80–90%, to be 1.5 kU/l and 0.6 kU/l in children aged 13–18 months, 6 kU/l and 2 kU/l in children aged 19–24 months, and 14 kU/l and 5 kU/l for 3-year-olds.

D'Urbano et al. [31] and Ayats-Vidal et al. [39] determined optimal cut-off points for facilitating the diagnosis of raw milk allergy, using cow's milk extract and milk allergens, in children with suspected IgE-dependent CMPA. D'Urbano et al. found 100% PPV scores (ImmunoCAP) for 34.27 kU/l α-LA asIgE and 9.91 kU/l β-LG asIgE, while 0.78 kU/l casein asIgE achieved 85% PPV, and 16.6 kU/l cow's milk extract asIgE obtained only 41% sensitivity and 93% PPV. In the Spanish study [39], the lowest sensitivity (ImmunoCAP) was noted for cow's milk extract asIgE (3.86 kU/l; sensitivity = 59.5%; PPV = 96.6%), while the highest PPV was observed for asIgE for casein and β-LG (PPV = 91%; 0.95 kU/l and 1.6 kU/l, respectively), and asIgE for α-LA (PPV = 94%; 2.25 kU/l).

Monitoring the course of CMPA based on the asIgE values for cow's milk allergens

The present study used classification trees as part of an innovative approach to predict the course of CMPA in children. This method allowed the asIgE values for selected cow's milk allergens obtained in the first phase of the study to be determined; these were found to predict the persistence of the allergy or the development of milk tolerance 1 year after diagnosis with high accuracy. The classification tree method is frequently used in medical decision-making because it can detect relationships between several variables that might otherwise go unnoticed by other statistical methods.

In the present study, the persistence of CMPA was indicated by an asIgE level for cow's milk extract > 1.95 kU/l or asIgE for β-LG > 13.31 kU/l and α-LA > 10.48 kU/l, as measured by the FEIA method. The resolution of CMPA symptoms, however, was predicted when the asIgE for cow's milk extract was ≤ 1.95 kU/l, or asIgE for β-LG ≤ 13.305 kU/l or asIgE for α-LA ≤ 0.22 kU/l and casein ≤ 0.94 kU/l. The determined values had approximately 75% accuracy and PPV, and around 90% sensitivity, making them a useful prognostic tool. On the other hand, the fact that the asIgE concentration for α-LA ≤ 0.22 kU/l is only slightly higher than the detection level of the FEIA test (0.1 kU/l) raises doubts about its diagnostic value. For this reason, the asIgE values determined in the classification trees for BSA were not considered, as it is not a useful diagnostic tool for milk allergens. Nevertheless, the asIgE values determined for the other cow's milk allergens seem to have practical value, although no studies appear to have used this method to determine predictive values.

Numerous studies have been conducted to identify appropriate prognostic tools for monitoring food allergies in children. A univariate analysis in a study of Korean children with CMPA by Kim et al. [40] estimated the presence of 5 kU/l cow's milk asIgE during the first reaction to milk to be associated with 30% likelihood of developing milk tolerance at 24 months of age; in addition, 52 kU/l was associated with a 10% likelihood. A logistic regression analysis by Shek et al. [41] confirmed a strong relationship between a decrease in asIgE for cow's milk and the probability of developing tolerance; for a child with CMPA up to 4 years of age during the first OFC, the probability of developing tolerance was 31% with a 50% reduction in asIgE, 45% with a 70% reduction, 66% with a 90% reduction, and even 94% with a 99% reduction within 12 months. However, if the reduction of asIgE for milk by 90% occurred over a longer timespan, i.e. 5 years, the likelihood of developing tolerance was lower (56%). These estimated values could potentially delay performing an OFC until the expected reduction in asIgE is achieved, thus avoiding inconveniences and the risk of a positive OFC result. Furthermore, Kim et al. [40] report that the initial concentration of asIgE for milk was 4.63 kU/l in children who later acquired tolerance, compared to 29.1 kU/l in children with persistent allergy.

This study is the first prospective study of Polish children to evaluate the use of molecular tests in the diagnosis and monitoring of CMPA, and the risk assessment for anaphylaxis. One of its key points is its use of innovative methods for predicting the course of CMPA in children using classification trees. However, it is limited by the small size of the study group and the fact that all were recruited from a single centre.

In summary, CMPA is one of the most common types of allergies in the paediatric population, and is characterized by varying courses and prognoses. The conducted study attempts to evaluate the significance of CRD in the diagnosis of CMPA in children. Although markers of clinical reactivity vary between different CMPA phenotypes, casein remains the best marker in both baked milk allergy and raw milk allergy. Our findings indicate that the measurement of cow's milk allergens by molecular methods alone is insufficient for the diagnosis and monitoring of CMPA, and although such approaches have greater clinical value than skin tests, they cannot replace oral food challenges [42]. Nevertheless, the most useful asIgE types for monitoring CMPA are casein, α-LA, and β-LG.

This area demands further research, especially multicentre studies on large representative populations of Polish children. The findings could contribute to improving allergy diagnostics and perhaps lead to replacing the OFC with modern diagnostic methods, including CRD.

Conclusions

Although markers of clinical reactivity vary between different phenotypes of CMPA, casein appears to be the best diagnostic marker in both baked milk allergy and raw milk allergy when measured by the FEIA method. For monitoring the course of CMPA, the most useful markers are asIgE for casein, α-LA, β-LG, and cow's milk extract, again measured by the FEIA method. Measuring cow's milk allergens solely by molecular methods is insufficient for the diagnosis and monitoring of CMPA and cannot replace oral food challenges. The assessment of the significance of allergens determined by molecular methods in CMPA diagnosis requires further research.