Introduction

Cervical cancer is the most common malignant tumour of the female reproductive tract. According to Global Cancer Statistics 2022, cervical cancer ranks fourth in incidence and mortality among female cancers worldwide, with 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths [1]. Although human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and cervical cancer screening can reduce the incidence of cervical cancer to some extent, for economic, resource, and technological reasons, their implementation and long-term effects on patients in low-to middle-income countries are still not satisfactory; as a result, the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer remain high in these nations [2].

Therefore, effective treatment options for cervical cancer are particularly important. Surgical treatment is mainly used for early-stage cervical cancer, whereas radiotherapy and chemotherapy are usually employed for advanced-stage cervical cancer. Cisplatin, carboplatin, paclitaxel and gemcitabine are commonly used chemotherapeutic agents for treating cervical cancer, and cisplatin plus paclitaxel is considered a first-line option [3, 4]. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy are promising for patients with advanced cervical cancer but cause a series of serious complications, such as haematological toxicity, neurotoxicity, and gastrointestinal toxicity [5, 6]. Therefore, safer treatments for cervical cancer are urgently needed.

With the development of 16S rRNA sequencing technology, researchers have shown that Lactobacillus spp. are the dominant components of the microbial flora in the vaginas of healthy women. Lactobacillus can maintain vaginal homeostasis, regulate inflammation in the genital tract and significantly inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, and Staphylococcus aureus [7, 8]. Oral administration of Lactobacillus modulates innate and adaptive immunity to attenuate bacterial vaginosis caused by Gardnerella vaginalis infection [9]. In addition, vaginal microenvironments dominated by Lactobacillus can reduce the risk of HPV infection and hinder the progression of cervical cancer [10, 11]. Since Lactobacillus is generally recognized as safe [12], it has been widely used for the prevention and treatment of systemic diseases, such as maintaining intestinal homeostasis [13], treating radiation-induced diarrhoea and chemotherapy-induced diarrhoea [14, 15], and lowering blood sugar and blood lipid levels [16–18]. In recent years, the antitumour effects of Lactobacillus in vivo and in vitro have attracted the attention of researchers. Lactobacillus plantarum can prevent and inhibit colon cancer by modulating autophagy or the tumour microenvironment [19]. Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC4356 culture supernatants inhibit MCF-7 cell proliferation and reduce the volume of MCF-7 tumour in nude mice [20]. Research by Salemi et al. showed that Lactobacillus rhamnosus inhibits cell proliferation by blocking colon cancer and melanoma cell cycle progression at G2/M phase [21]. Previous studies have shown that the absence of Lactobacillus spp. is associated with the development of cervical cancer. Researchers have found that supplementation with specific strains of Lactobacillus is an effective treatment for cervical cancer. A study by Nouri et al. showed that Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus crispatus inhibit proliferation of HeLa cells [22], and that Lactobacillus casei can promote apoptosis of cervical cancer cells [23]. Since the anticancer effects of Lactobacillus are highly strain-specific and cell-specific [24], the effects of specific strains of Lactobacillus warrant further investigation.

The Lactobacillus brevis YNH strain used in this study was first isolated from the vaginas of healthy women and identified by our research group. The interactions between Lactobacillus brevis YNH and tumours have yet to be studied and reported. In this study, HeLa cells were cultured with different concentrations of Lactobacillus brevis YNH to study the effects of Lactobacillus brevis YNH on cell proliferation and apoptosis and to elucidate the potential underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, the anti-cervical cancer effect of Lactobacillus brevis YNH was verified using in vivo experiments. The results provide a new candidate bioactive substance for the clinical treatment of cervical cancer.

Material and methods

Bacterial suspension preparation and cell culture

Lactobacillus brevis YNH was isolated from the vaginas of healthy women. The bacteria were grown in de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe media (Solarbio, China) at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 18 hours. Live bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (8 minutes, 8000 g, RT). The bacteria were then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA). The bacterial concentration was measured by detecting the OD600 using a spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, USA). The HeLa cervical cancer cell line and HaCaT human immortalized epidermal cell line were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Kuming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. HeLa and HaCaT cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cell viability

HeLa and HaCaT cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 103 cells per well. After the cells had adhered, the DMEM was discarded, and 200 µl of different concentrations (multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 0, 10, 100, 1000, or 10,000 CFUs/well) of Lactobacillus brevis YNH was added, followed by further incubation for 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. Moreover, Lactobacillus brevis YNH was cocultured with HaCaT cells at an MOI of 1000 or 10,000 for 24 and 48 hours in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The absorbance of the cells was measured at OD450 with a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, USA) every 24 hours.

Microscopy and photography

HaCaT cells (1 × 105) were cocultured with Lactobacillus brevis YNH at MOIs of 1000 and 10,000, respectively. The growth status of these cells was recorded at 0, 24, and 48 hours using a microscope (Leica, Germany).

Cell cycle

HeLa cells (approximately 5 × 105) were seeded in a T25 flask. After the cells adhered, the DMEM was removed and replaced with 4 ml of different concentrations (MOI = 0, 1000, or 10,000 CFUs/well) of the Lactobacillus brevis YNH suspension for 48 hours. The cells were harvested, resuspended in PBS, and fixed overnight with prechilled 70% ethanol. Before staining, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and 25 µl of a 20X propidium iodide staining solution and 10 µl of 50X RNase A buffer were added, followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min. The cell cycle analysis was performed using a flow cytometer (BD FACS Aria II; BD Biosciences). The data were analysed using ModFit LT software.

Apoptosis assay

HeLa cells were treated with Lactobacillus brevis YNH (MOI = 0, 1000, or 10,000 CFUs/well) for 48 hours. Then, the cells were harvested, washed with precooled PBS, added to 500 µl of 1X binding buffer and resuspended gently to avoid excessive pipetting, which would cause phosphatidylserine exposure in the cell membrane, resulting in false positive results. Annexin V-FITC (BD, USA) and PI solutions (5 µl each) were added to 100 µl of the cell suspension and mixed well, and the cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. The stained cells were analysed using flow cytometry (FCM) (BD FACS Aria II; BD Biosciences, USA).

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) measurement

After coculture with different concentrations of Lactobacillus brevis YNH (MOIs of 0, 1000, or 10,000) for 48 hours, 10 µM CCCP was added to the positive control wells and incubated at 37°C for 20 min, after which the cells were washed twice with PBS. Next, 1 ml of JC-1 staining solution (Beyotime, China) was added to each well, and after incubation for 20 min, the cells were washed with JC-1 staining buffer, followed by the addition of 2 ml of complete medium. Red fluorescence represents the inner mitochondrial membrane potential of the cell, whereas green fluorescence represents the outer mitochondrial membrane potential.

Transcriptome sequencing

HeLa cells (5 × 105) from the group treated with Lactobacillus brevis YNH (MOI = 10,000) for 48 hours were lysed with TRIzol (Solarbio, China) and sent to Biomarker (Beijing, China) for next-generation sequencing. The RNA concentration was measured with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and the RNA integrity was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Finally, the library quality was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system, and the libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform. All sequencing data will be deposited in the BioProject (once the paper is accepted for publication) and will be publicly available (once the paper is accepted for publication).

Identification and analysis of differentially expressed genes

The differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 with the following screening criteria: fold change (FC) ≥ 2 and p < 0.01. Analyses of the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases were performed using BMKCloud (www.biocloud.net) to elucidate the potential molecular mechanisms involved.

Western blot

After the cells were digested, 100 µl of RIPA buffer (Solarbio, China) containing 1% protease inhibitor and 1% phosphatase inhibitor was added to the cells, which were subsequently lysed on ice for 20 min, followed by centrifugation at 4°C and 12,000 rpm for 15 min. A BCA kit (Beyotime, China) was used to quantify the protein concentration. Proteins were separated on 8–10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in tris-buffered saline with tween 20 for 2 hours. The membranes were then immersed in a diluent containing the primary antibody and incubated overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then incubated with a rabbit secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 hour. The protein bands were visualized using an ECL western blot kit (CWBIO, China). Antibodies against Bax (ab32503), Bcl-2 (ab182858), AKT (ab18785), and p-AKT (ab81283) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); antibodies against caspase-8 (13423-1-AP), cyclin E1 (11554-1-AP), and CDK2 (10122-1-AP) and rabbit secondary antibodies (SA0000-1-2) were purchased from Proteintech (Wuhan, China); the antibody against cleaved caspase-3 (A11021) was purchased from ABclone (Wuhan, China); and antibodies against caspase-3 (#14220) and GAPDH (ET1601-4) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, USA) and HUABIO (Hangzhou, China), respectively. Detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Mouse xenograft tumour model

The animal experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics Review Committee of Kunming Medical University (approval number: kmmu20211090). Thirty-two female BALB/c nude mice (6–8 weeks old, weighing 20–25 g) were maintained in a room with a 12 hours light/dark cycle at 22 ±2°C. The mice were allowed to eat and drink freely for one week and then randomly divided into four groups (n = 8): the control (C), Lactobacillus brevis YNH (L), cisplatin (CIS), and Lactobacillus plus cisplatin (LCIS) groups. The mice in the L and LCIS groups were orally gavaged with 200 µl of Lactobacillus brevis YNH (5 × 1010 CFU/ml) suspended in saline for 14 days. The mice in the C and CIS groups received the same dose of saline. After 14 days, each mouse was subcutaneously inoculated with 200 µl (2.5 × 107/ml) of HeLa cells in the right anterior axillary branch. After the tumour cell inoculation, the mice in the L group continued to receive 200 µl of Lactobacillus brevis (5 × 1010 CFU s/ml) by gavage daily, and mice in the CIS group were intraperitoneally injected with an equal volume of cisplatin (Li Aikang, Yunnan Botanical Pharmacy) in a saline solution (2 mg/kg) on the 7th and 14th days. The mice in the LCIS group were administered the same treatments described above for the mice in the L and CIS groups. The mice in the C group were gavaged with the same amount of saline every day until the end of the experiment. Once a week, the length and width of the tumours were measured with Vernier callipers after they had grown to the size of a grain of rice. Tumour volumes were calculated, and a mouse tumour volume growth curve was drawn using the following formula: V = L × W2/2, where L is the length (mm), W is the width (mm), and V is the volume of the tumour. The maximum tumour volume was less than 1000 mm3. The mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the tumour volumes were recorded according to Directive 2010/63/EU [25]. However, one mouse in the LCIS group did not develop a tumour; therefore, this mouse was excluded from the analysis.

Biochemical analysis

Before the mice were euthanized, blood was obtained from the retro-orbital sinus and added to a heparin-containing tube. The liver function indices of the mice, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), total protein (TP), and albumin (ALB) levels, and the renal function indices, including creatinine (CREA) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels, were measured with an automatic biochemical analyser (OLYMPUS AU400, Japan).

Haematoxylin and eosin staining

Mouse hearts, livers, and kidneys were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours. The tissues were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin wax and sliced. Haematoxy-lin and eosin staining was performed using a standard protocol [26]. Histological images were obtained using a light microscope (Leica, Germany).

Results

Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibits proliferation of HeLa cells without affecting normal cells

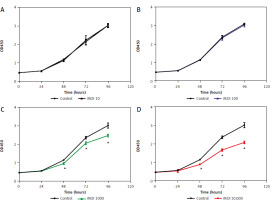

The effects of Lactobacillus brevis YNH on the proliferation of HeLa cells were investigated via CCK8 assays. During coculture for 96 hours, only a small difference (p > 0.05) in absorbance was observed among the control, MOI 10, and MOI 100 groups, indicating that Lactobacillus brevis YNH at MOIs of 10 and 100 did not significantly inhibit the proliferation of HeLa cells within 96 hours (Figs. 1 A, B). However, as shown in Figures 1C, D, the administration of Lactobacillus brevis YNH at MOIs of 1000 and 10,000 inhibited the proliferation of HeLa cells from 48 hours (p < 0.05). Over time, the inhibitory effect increased accordingly; an approximately 30% decrease in proliferation was observed in the MOI 10,000 group at 96 hours, with a smaller 20% decrease detected in the MOI 1000 group at 96 hours. As a result, we chose to administer Lactobacillus brevis YNH at MOIs of 1000 and 10,000 to cultured with HeLa cells for 48 hours in subsequent experiments.

Fig. 1

Effects of different Lactobacillus brevis YNH concentrations on proliferation of HeLa cells. Effect of multiplicity of infection of 10, 100, 1000, 10000 of Lactobacillus brevis YNH on absorbance of HeLa cells (A–D)

* p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance

Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to analyse the data.

MOI – multiplicity of infection

Unlike pathogenic bacteria, which cannot coexist with cells, Lactobacillus brevis YNH is a commensal bacterium isolated from the vagina of healthy women that can live in symbiosis with normal cells. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, Lactobacillus brevis YNH did not inhibit HaCaT cell proliferation within 48 hours. The number of HaCaT cells in each group increased over time, the cell morphology was normal, and the cell density was similar at each time point (Suppl. Fig. 2). To some extent, these results indicated that Lactobacillus brevis YNH does not inhibit normal cell growth.

Lactobacillus brevis YNH induces HeLa cell cycle arrest at S phase

The effect of Lactobacillus brevis YNH on the cell cycle of HeLa cells was determined by FCM. As shown in Figures 2 A–C, the proportion of cells in the S phase increased significantly. The control group had a value of 28.89%, and the values of the cells treated with MOIs of 1000 and 10,000 were 35.70% and 48.89%, respectively. As shown in Figures 2 D–F, the expression of CDK2 and cyclin E1, which are closely related to the regulation of S phase, decreased after treatment with increasing concentrations of Lactobacillus brevis YNH (p < 0.05), suggesting that Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibits the proliferation of HeLa cells by reducing the expression of CDK2 and cyclin E1.

Fig. 2

Lactobacillus brevis YNH induces HeLa cell arrest at S phase. Changes in the cell cycle of HeLa cells cocultured with different concentrations (multiplicity of infection of 0, 1000, 10,000) of Lactobacillus brevis YNH for 48 hours (A–C), proportion of cells in each phase of the cell cycle in each group (D), western blot analysis of the levels of the S phase-related proteins cyclin E1 and CDK2 in all groups of HeLa cells (E, F)

* p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments.

MOI – multiplicity of infection

Lactobacillus brevis YNH promotes apoptosis of HeLa cells

The effect of Lactobacillus brevis YNH on the apoptosis of HeLa cells was assessed by FCM, and the effect of Lactobacillus brevis YNH on the mitochondrial membrane potential of HeLa cells was assessed via the JC-1 assay. As shown in Figures 3 A–C, compared with that in the control group (5.77% apoptotic cells), after coculture with Lactobacillus brevis YNH, the proportion of apoptotic HeLa cells increased to 10.11% and 14.858%, respectively. These results indicated that Lactobacillus brevis YNH promoted the apoptosis of HeLa cells (p < 0.05). The JC-1 assay revealed that HeLa cells exposed to different concentrations of Lactobacillus brevis YNH presented a concentration-dependent decrease in red fluorescence and an increase in green fluorescence (Fig. 3 E), indicating that the mitochondrial membrane potential of the HeLa cells was reduced. As shown in Figures 3 F, G, HeLa cells treated with Lactobacillus brevis YNH significantly promoted the cleavage of caspase-3 and caspase-8, and increased the expression of Bax, whereas the expression of Bcl-2 decreased (p < 0.05), collectively suggesting enhanced apoptosis signalling.

Fig. 3

Lactobacillus brevis YNH promotes apoptosis of HeLa cells. Effects of different concentrations of Lactobacillus brevis YNH on apoptosis of HeLa cells, as determined by flow cytometry (A–C), proportion of apoptotic cells in each group (D), fluorescence intensity of JC-1 in HeLa cells cocultured with different concentrations of Lactobacillus brevis YNH for 48 hours; the scale bar represents 50 μm (E) Western blot analysis of caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3, caspase-8, cleaved caspase-8, Bax, and Bcl-2 protein levels in HeLa cells. GAPDH was used as the loading control (F, G)

* p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Differential gene expression and enrichment analyses of HeLa cells cocultured with Lactobacillus brevis YNH

Transcriptome sequencing was performed to further explore the mechanism underlying the anticancer effect of Lactobacillus brevis YNH on HeLa cells. As shown in Figure 4 A, a total of 4221 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified and compared with the control group, HeLa cells treated with Lactobacillus brevis YNH presented 2405 upregulated DEGs and 1805 downregulated DEGs (FC > 2, p < 0.01). The Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of the DEGs revealed enriched cellular components, including RNA processing, nuclear transport, internal protein transport, and the mitotic cell cycle (Fig. 4 B). The enriched molecular functions included the cytosol, nucleoplasm, mitochondrion, internal membrane-bound organelles, and nucleolus (Fig. 4 C). The enriched biological processes included RNA and adenosine triphosphate binding (Fig. 4 D). The KEGG pathway classification of the DEGs revealed that genes were mainly enriched in the pathways of cancer and HPV infection in the “Human Diseases” subgroup. In the cellular process subgroup, the DEGs were associated with endocytosis, cellular sensitivity, and the cell cycle (Suppl. Fig. 3). Importantly, in the environmental information processing subgroup, the DEGs were mainly enriched in the MAPK signalling pathway and the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway (Fig. 4 E); both are canonical pathways related to cancer. In addition, the KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the DEGs were enriched in the cell cycle, platinum drug resistance, RNA transport, endocytosis, and cellular sensitivity, among other processes (Fig. 4 F).

Fig. 4

Differential gene expression and enrichment analyses of HeLa cells cocultured with Lactobacillus brevis YNH. Differentially expressed genes are presented in a volcano plot. Upregulated genes are shown in red; downregulated genes are shown in green; fold change > 2, p < 0.01 (A), the top 10 enriched terms in the cellular component, molecular function, and biological process categories, as determined by the Gene Ontology (GO) analysis. The genes on the left side of the outer circle are differentially expressed genes. The colour of the gene blocks represents the magnitude of differential expression, with red indicating upregulated genes and blue indicating downregulated genes. Gene Ontology terms are shown on the right side of the outer circle, with different colours representing different terms. The lines connecting the genes and GO terms represent their enrichment relationships (B–D) and environmental information processing of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Y-axis: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways; X-axis: numbers and percentages of genes annotated to the KEGG pathway (E) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs; the X-axis represents the gene number, which is the number of genes annotated in each entry; the Y-axis represents each pathway entry; the colour of the bars represents the q-value obtained from hypergeometric testing (F)

GO – Gene Ontology, DEGs – differentially expressed genes, KEGG – Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

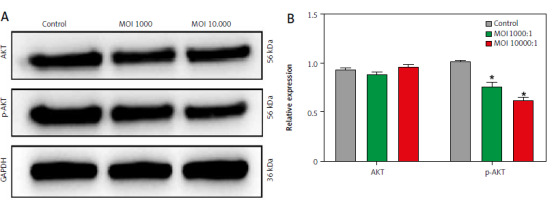

Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibits the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway

The transcriptome results revealed two top pathways: the MAPK pathway and the PI3K/AKT pathway. The PI3K/AKT signalling pathway is closely related to cell proliferation, the cell cycle, and apoptosis [27, 28]. Therefore, we further investigated whether the antitumour properties of Lactobacillus brevis YNH are related to the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. As shown in Figures 5 A, B, compared with those in the control group, the relative expression levels of AKT in the MOI 1000 and MOI 10,000 groups remained unchanged, and the relative level of p-AKT (Ser473), which is responsible for signal transduction, was clearly decreased after treatment with increasing concentrations of Lactobacillus brevis YNH (p < 0.05). Collectively, the above results suggest that Lactobacillus brevis YNH may exert its antitumour effects by inhibiting PI3K/AKT-related proteins. However, the complete mechanism needs to be further investigated.

Fig. 5

Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibits the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Western blot analysis of AKT and p-AKT protein levels in HeLa cells (A, B)

* p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

MOI – multiplicity of infection

Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibits the tumour growth of HeLa cells in vivo without toxic effects

We established a xenograft tumour model by subcutaneously injecting HeLa cells into nude mice to determine whether Lactobacillus brevis YNH has a similar anticancer effect in vivo. The experimental grouping and workflow are shown in Figure 6 A. As shown in Figures 6 B–D (C – mice gavaged with saline, L – mice gavaged with Lactobacillus brevis YNH, CIS – mice injected with cisplatin, LCIS – mice gavaged with Lactobacillus brevis YNH and injected with cisplatin), although the tumours in the L group were not smaller than those in the CIS and LCIS groups, the tumours in the L group were significantly smaller than those in the C group (p < 0.05), indicating that Lactobacillus brevis YNH alone inhibited the growth of subcutaneous cervical cancer xenografts, even when it was orally administered. The cisplatin and LCIS groups also had much smaller tumours than the C group did (p < 0.05). However, compared with the nude mice treated with cisplatin alone, the combination of Lactobacillus brevis YNH and cisplatin did not result in a significant reduction in tumour size; however, the LCIS group seemed to have more evenly distributed tumour sizes, and the three largest tumours in the LCIS group were somewhat smaller than the three largest tumours in the CIS group. This result may be because Lactobacillus brevis YNH and cisplatin had relatively weak synergistic anticancer effects in this trial or because we did not identify the best combination strategy at this time.

Fig. 6

Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibits growth of HeLa cells in vivo. Schematic diagram of the animal experiments (A), growth curves for xenograft tumours; the results of repeated-measures ANOVA (B), general view of subcutaneous tumours in nude mice (C), representative images of tumours isolated from nude mice at 28 days after implantation of HeLa cells (D), liver function (E) and renal function (F) of each group of nude mice at the end of the experiment

ALB – albumin levels, ALT – alanine aminotransferase, AST – aspartate transaminase, BUN – blood urea nitrogen, CREA – creatinine, TP – total protein

Relevant biochemical parameters were tested to investigate whether Lactobacillus brevis YNH has toxic effects on the liver and kidneys of tumour-bearing mice, ALT, AST, TP, and ALB are important indicators for assessing liver function, whereas CREA and BUN are indicators used to assess kidney function. As shown in Figures 6 E, F, no significant differences in ALT, AST, TP, ALB, or BUN levels were observed among the four groups (p > 0.05), but the activity of CREA in the L and LCIS groups was lower than that in the C and CIS groups (p < 0.05). The results showed that Lactobacillus brevis YNH treatment had no significant effects on the liver or kidney of tumour-bearing mice.

Discussion

Cervical cancer is a high-incidence malignant tumour of the female reproductive tract. Treatment methods such as surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy have different side effects on patients [6, 29, 30]. Some Lactobacillus strains can selectively inhibit the proliferation of tumour cells without affecting healthy cells [31] and hence represent a promising biologically active substance for treating cervical cancer. Studies have shown that Lactobacillus gallinarum [32], Lactobacillus plantarum ZS2058 [33], Lactobacillus brevis MK05 [34] and other lactobacilli can inhibit tumour growth. However, the anticancer effects of Lactobacillus are highly strain- and cell type-specific. In this study, we identified the anticancer effects of Lactobacillus brevis YNH on cervical cancer.

Uncontrolled proliferation and the evasion of apoptosis are important cell characteristics that allow rapid tumour progression. Similarly, a variety of lactobacilli exert anticancer effects by inhibiting tumour growth and promoting apoptosis [20, 35, 36]. Our study revealed that Lactobacillus brevis YNH increased the proportion of cells in S phase in a concentration-dependent manner. Similar to our findings, Wang et al. [37] incubated Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus gasseri, and Lactobacillus jensenii supernatants with cervical cancer cells and reported that the cell cycle was arrested at S phase by downregulating the expression of CDK2 and cyclin A. Other studies have shown that L. rhamnosus can upregulate P21 to block the cell cycle of ME-180 cervical cancer cells in G1 phase, and the cell cycle of colon cancer and melanoma cells in G2/M phase [21, 38]. Overall, Lactobacillus can inhibit cell proliferation by arresting the tumour cell cycle; however, different Lactobacillus species have different mechanisms of action. Cyclin E combines with CDK2 to promote the transition of cells between the G1 and S phases, and the amount of cyclin E-CDK2 complexes peaks in the late G1 and early S phases and then decreases with the progression of the cell cycle [39]. Bi et al. reported that when the cell cycle was arrested at S phase, the expression of cyclin E and CDK2 was reduced [40]. Our study suggested that Lactobacillus brevis YNH could effectively block the cell cycle in S phase by reducing the levels of cyclin E1 and CDK2 proteins.

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that occurs through two main pathways: endogenous and exogenous apoptosis [41, 42]. The endogenous pathway is related to changes in the mitochondrial membrane permeability, which leads to an increase in the levels of pro-apoptotic proteins of the Bax family and a decrease in the levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 in the outer mitochondrial membrane [43]. Caspase-8 is an upstream apoptotic protein in the exogenous apoptotic pathway that cleaves the downstream apoptotic proteins caspase-3, caspase-6 and caspase-7 to induce apoptosis [44]. Our study revealed that the mitochondrial membrane potential of HeLa cells decreased after Lactobacillus brevis YNH treatment, along with increased Bax and decreased Bcl-2 expression. In addition, the levels of cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-8 increased. These results indicate that Lactobacillus brevis YNH affects HeLa cell apoptosis through endogenous and exogenous apoptotic pathways. Many strains of Lactobacillus play anticancer roles by promoting tumour cell apoptosis [34, 45, 46]. Similarly, Riaz Rajoka et al. [47] cocultured supernatants from three strains of Lactobacillus casei with HeLa cells for 24 hours and reported that the expression of Bax and Bad was upregulated, the expression of Bcl-2 was downregulated, and HeLa cells underwent apoptosis. Sungur et al. [48] found that Lactobacillus gasseri extracellular polysaccharide isolated from the vagina upregulated Bax in a dose-dependent manner and promoted HeLa cell apoptosis. In conclusion, Lactobacillus brevis YNH can effectively promote the apoptosis of HeLa cells and exert antitumour effects.

Omics methods have been widely used to explore disease mechanisms. We performed transcriptome sequencing of HeLa cells cocultured with Lactobacillus brevis YNH and GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of the DEGs, attempting to reveal the specific mechanism by which Lactobacillus brevis YNH affects HeLa cells. The differentially expressed genes were significantly enriched in the cell cycle, RNA transport, endocytosis, cellular sensitivity, the MAPK signalling pathway, and the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Endocytosis is a cellular process that mediates receptor internalization, nutrient uptake, and signal transduction regulation, and both bacteria and viruses can enter cells through this process [49, 50]. The endocytosis of pathogenic bacteria can cause significant cell damage or even death. Unlike phagocytosis, the endocytosis of commensal bacteria is usually nonpathogenic to cells. Numerous studies have reported that Lactobacillus can be spontaneously internalized by epithelial cells [51, 52]. The enriched terms suggest that Lactobacillus brevis YNH might be internalized into HeLa cells via endocytosis, which may involve multiple signal transduction processes and could be related to increased RNA transport and cellular sensitivity. At this stage, we have yet to elucidate the specific mechanism by which Lactobacillus brevis YNH is internalized by cells, which is an exciting topic that deserves further investigation.

The PI3K/AKT signalling pathway is ubiquitous in various organisms and can regulate the cell cycle and apoptosis of various tumours, such as cervical cancer, gastric cancer, and lung cancer [53–55]. In cervical cancer, the PI3K/AKT pathway is a target of many anticancer drugs or molecules. Oxyresveratrol reduces the proliferation and migration of cervical cancer cells by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT pathway [27]. FNDC5 decreases AKT phosphorylation in cervical cancer xenografts in mice, resulting in a reduction in the tumour volume [56]. The MAPK signalling pathway is associated with cell growth, development, the stress response, and inflammation. Ras/Raf/ERK, JNK, p38/MAPK, and ERK are four subpathways within the MAPK pathway that play roles in tumour development [57, 58]. Compared with the complex MAPK pathway, we first chose the more important PI3K/AKT pathway to study the possible mechanism by which Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibits cervical cancer. The western blot results indicated that coculturing HeLa cells with Lactobacillus brevis YNH reduced the levels of p-AKT, which likely reduced signal transduction. Collectively, these results suggest that Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibits HeLa cell proliferation and promotes HeLa cell apoptosis through the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway.

Many studies have shown that oral Lactobacillus is a feasible antitumour agent in vivo. Si et al. [59] reported that the oral administration of live Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) significantly inhibited colorectal cancer in mice, whereas heat-killed LGG failed to inhibit colon cancer. They also found that the intratumoural administration of live LGG in mice did not control tumour growth. Another study showed that the oral administration of Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 314 and Lactobacillus fermentum NCIMB 5221 successfully inhibited colon cancer growth [60]. Moderately heat-killed Lactobacillus crispatus can reduce the volume of breast tumours in BALB/c mice and improve their survival rate [60]. Few studies of the anti-cervical cancer effects of oral Lactobacillus have been conducted, and the anticancer effects of Lactobacillus brevis YNH, which was independently isolated and identified by our team, are fascinating and promising. The tumour volume in the nude mice treated with Lactobacillus brevis YNH was visibly smaller than that in the control group, and the effects were quite prominent, indicating that Lactobacillus brevis YNH alone had an anticancer effect on subcutaneous cervical cancer xenografts, even when it was orally administered. Research conducted by Rahimpour et al. found that, compared with administration of capecitabine alone, the administration of Lactobacillus brevis R0011 and a chemical drug (capecitabine) resulted in smaller tumour volumes in mice [61]. These suggest that the coadministration of probiotics and chemotherapy drugs may enhance antitumour effects. Although we did not observe a significantly smaller tumour volume in the LCIS group than in the CIS group, the LCIS group seemed to have more evenly sized tumours, somewhat smoother tumour surfaces, and smaller sizes of the 3 largest tumours. In this study, Lactobacillus brevis YNH and cisplatin seemed to have a relatively weak synergistic anticancer effect; in addition, the cooperative effect might influence other factors in these tumours, which could be further investigated in the future.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibited HeLa cell proliferation, arrested HeLa cells at S phase, and promoted HeLa cell apoptosis, which could be related to the inhibition of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. In addition, Lactobacillus brevis YNH inhibited the proliferation of cervical cancer cells in vivo, with no apparent toxicity to the liver or kidney. In summary, our study revealed the anti-cervical cancer effects of Lactobacillus brevis YNH and its possible mechanism of action. The results of this study provide a theoretical basis for the application of Lactobacillus brevis YNH in the clinical treatment of cervical cancer.