Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) represents about 3.2% of all melanoma cases [1, 2], originating from melanocytes in the uveal structures: the iris, ciliary body and choroid. The incidence is approximately 6.6 per million people in Europe [2, 3].

Although a local disease control rate of over 90% has been achieved in patients with localized UM, this tumor has a high tendency to metastasize, resulting in high mortality; in fact, 40–50% of affected patients died of the disease within 10 years after the diagnosis. Metastases are localized in the liver in over 90% of cases [2–5].

The risk of UM metastasis is assessed using clinical factors (8th edition AJCC) and genetic profiling, which is extremely accurate in identifying patients with high-risk primary UM [6–8].

The goal of the treatment of UM is to achieve local control (LC) of the disease, to reduce the risk of metastasis, to spare the globe and, if possible, to maintain the visual function. Also, Laliscia et al. [9] found that patients who failed to achieve LC had a higher risk of distance metastases compared with patients who had LC in univariate (p = 0.030) and multivariate analysis (p = 0.030), so gaining LC can preserve life.

In the past years, enucleation was considered the standard therapy for these malignancies [10] until the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS), a multicenter randomized trial in 2001 showed that the 5-year overall survival (OS) rates after enucleation were comparable to those obtained after brachytherapy (BT) [11, 12].

BT has been used since 1930 to treat ocular tumors with radon sources [13]. Nowadays, BT is considered the first-line globe-sparing treatment for UM with iodine (125I) and ruthenium (106Ru) plaques. The adopted technique consisted in placing an assembly with sealed radioactive sources on the eyeball in proximity of the lesion for the time interval needed to administer the prescribed dose. Plaque BT is used for small- and medium-sized UM because the radiation dose decreases with increasing distance from the radioactive plaque; for this reason, in very large lesions the tumor apex cannot receive a sufficient radiation dose without compromising the sclera, due to the greater distance from the radiation source. Moreover, lesions that are close to the optic nerve or in the posterior pole are preferentially treated with other conservative approaches such as proton beam or stereotactic photon beam radiotherapy [14, 15], due to the risk of plaque displacement for anatomical reasons.

BT with 106Ru plaques can be considered as a first option for lesions within 6 mm in thickness and 16 mm in diameter [16], also because the dose distribution of this radiotherapy technique spares more healthy tissue.

The aim of this study was to retrospectively evaluate LC, progression-free survival (PFS), metastasis-free survival (MFS) and OS, correlated with clinical outcomes, in a cohort of patients affected by small and medium UM treated with 106Ru plaque BT.

Material and methods

In this retrospective study we analyzed a cohort of 127 patients affected by primary UM treated with 106Ru plaque BT between May 2005 and January 2024, after assessment at the Multidisciplinary Committee of Ocular Melanoma of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Pisana (AOUP); the Committee is generally composed of ophthalmologists, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, a medical physicist and a neuro-radiologist [17].

Inclusion criteria were Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) age ≥ 18 years, performance status (PS) ≤ 2, life expectancy > 6 months, thickness < 6 mm and/or diameter ≤ 16 mm. The first diagnosis of UM was made with a clinical examination with a baseline measurement of visual acuity by the Ophthalmologists of the Ophthalmic Oncological Surgery of the AOUP, with biomicroscopy, ophthalmoscopy, and standardized (A-scan B-scan) ultrasonography. Other examinations – color fundus photography, fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), indocyanine green angiography (ICGA), optical coherence tomography (OCT) – were used to confirm the diagnosis.

At the time of diagnosis, imaging studies including abdominal echography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), chest/abdominal/pelvic computed tomography (CT) and/or whole body FDG PET-CT were performed to assess tumor stage, using the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification of UM eighth edition [18]. Plaque implants were performed in accordance with American Brachytherapy Society (ABS) recommendations [16].

106Ru plaques are commercially manufactured in diffe-rent shapes. Two types of ruthenium plaques (CCA or CCB Eckert & Ziegler BEBIG, Berlin, Germany) with an external diameter of 15.5 mm and 20 mm respectively could be used, depending on the size of the tumor for adequate dose coverage of the tumor. The dose of 110 Gy was prescribed; the median radiation dose to the sclera surface was 268 Gy (range: 180–720). We use the Plaque Simulator treatment plan system (Eye Physics LLC, Los Alamitos CA, USA) to simulate the treatment and to prescribe the dose. The dose is prescribed on the plaque’s central axis to a distance from the inner plaque surface equal to the tumor apex height plus 1 mm (to take account of the scleral width) [19].

To define the clinical target volume (CTV), the sclera thickness is added in an apical direction and a margin at least of 1–2 mm is added in all directions to the tumor base diameter, since in the treatment planning several dosimetric uncertainties must be considered [19, 20].

Surgery was performed by the Ophthalmic Oncologist Surgeon in the presence of the radiation oncologist and the medical physicist. Tumor localization and margins were determined and marked with a transillumination technique and/or performing binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy, with sclera indentation, then a transparent dummy plaque was used for the suture positioning to the sclera. Muscle transposition was performed when necessary. Finally the ruthenium plaque was placed and the correct positioning was verified using ultrasound examination [21].

Plaques were sutured in place and the correct positioning was verified for all cases using intraoperative ultrasound [22].

Subsequently, the plaques were left in place for an inter-val of time depending on the source activity and the prescribed dose and then definitively removed.

Follow up was performed by radiation oncologists and ophthalmologists one week after radiotherapy and every two months from the end of surgery in the first year, and every six months for five years and every twelve months subsequently. Radiation toxicities were defined according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v 5.0) [23]. All the patients were observed until they died or until May 2024. The median follow-up of survivors was 72.5 months (range: 4–226 months).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 22 for Windows, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test was applied to evaluate differences between curves. Covariates that influenced survival (p < 0.1) after univariate analysis were included in a Cox regression model for multivariate analysis. The results of survival analysis are expressed using hazard ratios (HR) with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI); significance was set at 0.05 for LC, PFS, MFS and OS, and were assessed as the end-point, using the following covariates: patient age, sex, eye laterality, largest tumor diameter, height of the tumor, site, integrity of the Bruch membrane, tumor stage.

Results

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Patients and tumor characteristics

In our cohort we observed 99 (78.0%) choroidal melanomas, 5 (4.0%) ciliary body melanomas, 6 (4.7%) choroidal and ciliary body melanomas, 9 (7.0%) iris melanomas and 8 (6.3%) iris plus ciliary body melanomas.

Local tumor control, defined as absence of volume increment at the primary tumor site, was observed in 118 (93.0%) patients of our cohort. According to several authors [24, 25], tumor regression was evaluated as a percentage change of initial tumor height measured with B-scan ultrasonography. Other clinical signs considered when evaluating UM response are decreased intrinsic tumor vascularity, decreased tumor-related sub-retinal fluid, increased pigmentation, specific changes in orange pigment lipofuscin, resolution of drusenoid retinal pigment in epithelial detachments and increase in internal reflectivity on ultrasound.

Local progression was recorded in nine patients (7.1%): two of them (1.6%) also had distant metastasis. Seven patients were retreated using a second personalized globe-sparing radiotherapy approach with photon beam and one patient with proton beam stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS). One patient was retreated with 125I plaque BT.

Only one patient underwent enucleation for very large local progression after 116 months.

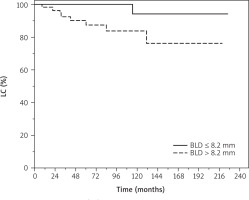

Patients affected by lesions with basal diameter ≤ 8.2 mm had non-significantly higher LC probability compared to those with greater basal diameter > 8.2 mm (HR = 1.32, 95% CI: 0.99–1.77, p = 0.051) in univariate analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Local control (LC) of patients with uveal melanoma treat ed with ruthenium-106 plaque brachytherapy. BLD – basal largest diameter

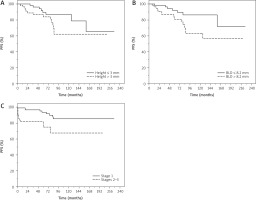

Younger patients aged ≤ 69 years had non-significantly higher probability of PFS compared with those aged > 69 years (HR = 2.35, 95% CI: 0.98–5.63, p = 0.055) in univariate analysis (data not shown). Patients with lesions with a height less than or equal to 3 mm had a significantly higher PFS probability compared with those with higher height > 3 mm (HR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.02–1.41, p = 0.024) in univariate analysis.

Moreover, lesions with basal diameter ≤ 8.2 mm had a significantly higher PFS probability compared to those with greater basal diameter (HR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.02–1.46, p = 0.024) in univariate analysis.

Patients with lesions of lower stage (1) had significantly higher probability of PFS compared with those with higher stage (2–3) (HR = 2.28, 95% CI: 1.12–4.64, p = 0.022) in univariate analysis; data were confirmed in multivariate analysis (HR = 2.71, 95% CI: 1.07–6.86, p = 0.035) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with uveal mela noma treated with ruthenium-106 plaque brachytherapy. BLD – basal largest diameter

Distant metastases were recorded in eight patients (6.3%): two of them (1.6%) had also local relapse. All the patients with distant disease showed only liver metastasis and underwent immunotherapy with tebentafusp in HLA-A*02:01-positive patients or with anti PD-1 nivolumab or pembrolizumab.

Younger patients aged ≤ 69 years had non-significantly higher probability of MFS compared with those aged > 69 years (HR = 2.77, 95% CI: 0.97–7.93, p = 0.056) in univariate analysis; the result was confirmed in multivariate analysis (HR = 2.35, 95% CI: 0.98–5.63, p = 0.055) (data not shown).

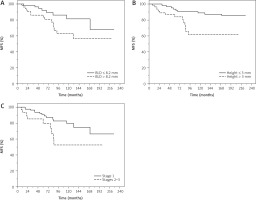

Patients with lesions with basal diameter less than or equal to 8.2 mm had non-significantly higher MFS probability compared to those with greater basal diameter > 8.2 mm (HR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.0.99–1.49, p = 0.055) in univariate analysis. Patients with lesions with a height less than or equal to 3 mm had a significantly higher MFS probability compared with those with higher height > 3 mm (HR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.03–1.48, p = 0.017) in univariate analysis.

Patients with lesions of lower stage (1) had significantly higher probability of MFS compared with those with higher stage (2–3) (HR = 2.75, 95% CI: 1.18–6.45, p = 0.019) in univariate analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Metastasis-free survival (MFS) of patients with uveal mela noma treated with ruthenium-106 plaque brachytherapy. BLD – bas al largest diameter

Seventeen patients (13.6%) died during the observation, eight of them (6.4%) because of distant progression, and the other nine (7.2%) because of age and/or comorbidities; one patient of this cohort (0.8%) died with local progression.

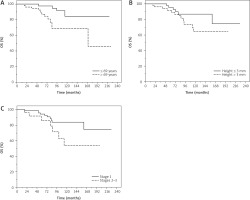

Patients aged ≤ 69 years had significantly lower risk of death compared with those aged > 69 years (HR = 3.52, 95% CI: 1.23–10.09, p = 0.019) in univariate analysis; data were confirmed in multivariate analysis (HR = 4.36, 95% CI: 1.38–13.78, p = 0.012).

Patients with lesions with a height less than or equal to 3 mm had a significantly better OS probability compared with those with higher height > 3 mm (HR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.01–1.46, p = 0.044) in univariate analysis.

Patients with lesions of lower stage (1) had significantly higher probability of better OS compared with those with higher stage (2–3) (HR = 2.23, 95% CI: 1.02–4.87, p = 0.043) in univariate analysis (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Overall survival (OS) of patients with uveal melanoma treated with ruthenium-106 plaque brachytherapy

LC was 95.2% and 85.0%, PFS was 89.4% and 75.0%, MFS was 93.0% and 78.5%, and OS was 95.9% and 86.4% at 5 and 10 years, respectively. Overall acute and late toxici-ties are reported in Table 2.

Table 2

Acute and late toxicities after ruthenium-106 brachytherapy for uveal melanoma

Thirty-four patients (26.8%) had one or more acute and late toxicities. The most common acute adverse events (CTCAE vs. 5.0) of grade 1–2 were watering eye (4.0%) and conjunctivitis (3.2%). No grade 3–4 acute toxicity was reported. The most common late adverse events of grade 1–2 were loss visual acuity (11.2%) and radiation retinopathy (8.8%); while the late adverse events of grade 3 were cataract (4.8%), neovascular glaucoma (0.8%) and radiation retinopathy (0.8%). No grade 4 late toxicity was reported.

Discussion

Since the randomized COMS multi-center clinical trial of 125I plaque BT vs. enucleation in 2001, which showed no difference in survival between BT and enucleation [11, 12], BT has been considered a very effective eye-preserving treatment modality but most of all the standard of care for UM.

106Ru is a β-emitter, with a limited depth of penetration, which causes less damage to the eye with an excellent LC [26]. Moreover, data of Egger et al. [27] strongly supported the hypothesis that the rate of death by metastases was influenced by local tumor control failure: improvement of the local tumor control rate resulted in a better survival rate.

This single-center retrospective study aimed to evaluate the long-term outcomes of 106Ru plaque treatment for UM: the major strength of our study is a long median follow-up of 72.5 months (range: 4–226 months), which demonstrated good outcomes with the applicators used. Also, Seibel et al. [28] in a cohort of 982 patients all treated with proton beam radiotherapy reported 3.6% local recurrence, which was correlated with higher risk for metastasis and reduced survival.

In our study, the largest basal diameter and the thickness were the most important clinical prognostic features for UM: the largest basal diameter for LC, PFS and MFS (p = 0.051; p = 0.055; p = 0.024, respectively) and thickness for PFS, MFS and OS (p = 0.024; p = 0.017; p = 0.044, respectively). Similarly, in a long-term study of 289 patients with UM, Kujala et al. [29] found a significant association between the largest basal diameter and UM-related death. In the regression analysis, the HR was 1.08 for each millimeter increase in tumor diameter. Shields et al. [6], in a cohort of 8,033 patients, found that each millimeter increase in tumor thickness was associated with about 5% increased risk for metastasis at 10 years, with a HR of 1.08 in the regression analysis.

Tumor AJCC stages had a progressively worse prognosis [18]. In our cohort, patients with lesions of a lower stage (1) had significantly better PFS compared with higher stage (2–3) (p = 0.022) in univariate analysis; the data were confirmed in multivariate analysis (p = 0.035). Moreover, patients with lesions of a lower stage (1) had significantly better MFS (p = 0.019) and OS (p = 0.043).

Older age is another unfavorable prognostic factor. Liu et al. [30] demonstrated that higher age was associated with lower survival rates. This may be because younger patients were mostly affected by iris melanoma, which is further away from the central macula and optic disc, with smaller tumor diameter and thickness, and a lower chance of tumor spread compared to other types of UM, while older patients have more comorbidities and more treatment complications.

Also, in our study patients aged ≤ 69 years had significantly lower risk of death than those aged > 69 years (p = 0.019) in univariate analysis; the data were confirmed in multivariate analysis (p = 0.012). Moreover, younger patients had non-significantly higher probability of MFS compared with those with older age (p = 0.056) in univariate analysis; the data were confirmed in multivariate analysis (p = 0.055).

Several studies have shown that the use of 106Ru plaque BT as eye-conserving treatment for UM allowed a tumor control rate of more than 95% in selected cases. In our population the prescribed dose was of 110 Gy. In the literature, great variability was reported in the dose prescription among different centers (80–120 Gy), but as reported also by Foti, the last agreed dose was 100 Gy [15, 19].

The dosimetric study of Foti et al. [15] showed several complications after radiotherapy which were frequent and mainly related to tumor thickness, radiation dose and distance between the tumor and optic nerve. In our cohort of patients with not very large tumors, located far from the optic nerve, we observed acute and late toxicities only in 26.8% of patients and no G4 acute or late toxicities were detected.

Moreover, we have not observed radiation toxicity related enucleation, while in the literature a 20–30% enucleation rate was reported, probably due to the small dimensions of the tumor and the customized dose prescribed to the apex of tumor and to the sclera [31, 32]. This study detected 11.2% loss of visual acuity, but we did not develop a predictive algorithm for visual impairment. Pagliara et al. [33] identified some factors significantly correlated with loss of visual acuity: tumor dimensions, distance of the posterior margin of the tumor from the fovea and from the optic nerve, BCVA < 6/12 at baseline and type of plaque. However, we believe that the main goal of this procedure must be tumor eradication, although late toxicities may occur to some extent.

According to Cennamo et al. [34], who reported a cancer-free survival rate of 99% and 85% at 5 and 9 years, 106Ru plaque BT has achieved a broad consensus and has become the most frequently used form of radiotherapy for patients affected by primary UM, with good LC and survival in patients with small and medium-size UM and a good quality of life due to the reduced incidence of treatment complications and toxicities [35]. Fionda et al. [36] elaborated on the role of BT in the treatment of UM. BT (interventional radiotherapy – IRT) has a great advantage, compared with enucleation, in terms of organ and function sparing. The authors described the complexity of IRT as multimodal approaches in UM management, which led to the establishment of multidisciplinary tumor boards to define targeted, patient-centered treatment strategies. Also it is necessary to follow clinical practice guidelines, so we concluded that this eye-sparing technique was carried out in a center with expertise so that IRT was safe and effective.