Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the second most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, typically presenting as painless lymphadenopathy. It usually originates from B cells, accounting for 35% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas and 70% of low-grade lymphomas [1]. FL occurs slightly more frequently in men than in women, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.2 : 1, and the average age of onset is 60–65 years [2]. However, when FL or other tumors arise in atypical locations, such as the posterior mediastinum, they pose a significant diagnostic challenge. The posterior mediastinum is a complex anatomical region containing various structures, including nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue, making it a common site for a diverse range of tumors, both benign and malignant [3]. Tumors in this region can present with nonspecific symptoms, such as pain or neurological deficits, complicating the clinical picture. The differential diagnosis for masses in the posterior mediastinum is broad, encompassing neurogenic tumors, lymphomas, metastatic lesions, and conditions such as thoracic peri-aortic fibrosis and IgG4-related disease [4]. This complexity underlines the importance of a thorough and systematic approach to evaluation, often requiring advanced imaging techniques and histopathological confirmation to establish a definitive diagnosis.

In this case report, we present a 65-year-old male patient with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease who developed persistent left flank pain. Imaging studies revealed a paravertebral mass in the posterior mediastinum, raising concerns about a neoplastic process. The eventual diagnosis of follicular lymphoma, classic type, Grade 1/2 (cFL 1/2) was established. This case highlights the diagnostic challenges associated with posterior mediastinal tumors and the critical role of multidisciplinary assessment in reaching an accurate diagnosis.

Initially, the pain was mild and responsive to analgesics, including pregabalin. However, over a period of 20 days, it gradually intensified and became refractory to pain management, prompting the patient’s referral to a local hospital for further evaluation. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a paraaortic mass extending from the T8 to T10 vertebrae. To gain additional insight, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, which confirmed the presence of a paravertebral neoplastic mass at the T9 level, encircling the descending aorta but without invasion of the spinal canal. Based on these imaging findings, several differential diagnoses were considered, including neuroendocrine tumors, lymphoma, metastatic lesions, peri-aortic fibrosis, and IgG4-related disease. However, the patient’s blood counts, biochemical parameters, as well as hormone and immunological tests, returned within normal limits, providing no further diagnostic clarity.

The patient was subsequently referred to a tertiary hospital, where comprehensive imaging studies were conducted. A CT scan of the brain revealed no abnormalities, with ventricular and subarachnoid spaces appearing age-appropriate and with no evidence of intracranial masses or midline shift. Thoracic CT identified heterogeneous paravertebral tissue enveloping the descending aorta from T9 to T11, reinforcing concerns about thoracic peri-aortic fibrosis, IgG4-related disease, or lymphoma (Figure 1). No significant lymphadenopathy or pleural effusion was detected. Additionally, abdominal CT did not reveal any focal lesions in solid organs. The only findings were mild bile duct dilation, atherosclerotic changes in the abdominal aorta, and a focal narrowing at the level of the celiac artery. Further assessment with on positron emission tomography (PET)/CT demonstrated increased metabolic activity within the paravertebral mass, with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 13.3, suggesting a malignant process (Figure 2). The lesion extended to the upper abdominal aorta and appeared to infiltrate the T9 vertebral body. Notably, a hypermetabolic lesion measuring 1.7 cm and with an SUVmax of 8.3 was detected in the left parotid gland (Figure 3). Additionally, enlarged axillary lymph nodes up to 1.2 cm with a hypermetabolic signal (SUVmax 8.6) were noted, along with mildly increased FDG uptake in the spleen (SUVmax 3) and hypermetabolic inguinal lymph nodes up to 1.3 cm in size, predominantly on the right side (SUVmax 10). Increased FDG uptake (SUVmax 9.3) was also observed near the distal portion of the left clavicle (Figure 3). A CT scan of the cervical area identified a solid, lobular lesion in the superficial lobe of the left parotid gland, measuring 27 × 16 × 21 mm, with no pathologically enlarged cervical lymph nodes (Figure 4). An initial fine-needle biopsy of the parotid lesion did not yield a definitive diagnosis, leading to an open biopsy of the inguinal lymph nodes. Histopathological examination revealed multiple fibrous tissue fragments containing four lymph nodes, ranging from 0.6 to 3.2 cm in diameter. Microscopic analysis showed architectural disruption with poorly defined lymphoid nodules of varying sizes, set within a stroma of small lymphoid cells and proliferating small blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry confirmed B-cell markers (CD20, CD79a, PAX-5, CD10, bcl-6, κ, λ, bcl-2) and T-cell markers (CD3, CD5), consistent with a diagnosis of follicular lymphoma, classic type, Grade 1/2 (cFL 1/2), according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 5th edition criteria.

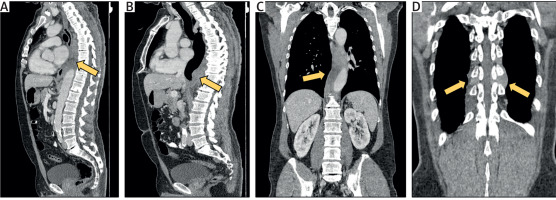

Figure 1

Computed tomography scan images showing the paravertebral mass surrounding the descending thoracic aorta from T5-T6 to T12. A, B – Coronary sections reveal diffuse, heterogeneously enhancing tissue both prevertebrally and postvertebrally (indicated by arrows). C, D – Sagittal sections display the mass extending into the bilateral vertebral foramina at T9-T10 and T10-T11 levels (indicated by arrows)

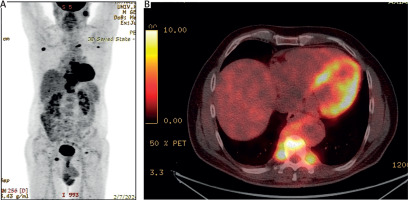

Figure 2

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography images demonstrating increased metabolic activity within the paravertebral mass (SUVmax 13.3). The images show the lesion’s infiltration of the T9 vertebral body and involvement of adjacent pleurovertebral segments of the ipsilateral posterior rib arches

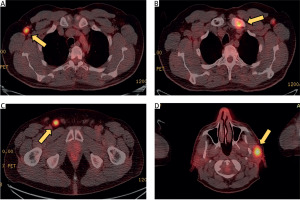

Figure 3

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography images showing regions of increased metabolic activity in various lymph nodes and bones. A – Hypermetabolic axillary lymph nodes (SUVmax 8.3). B – Increased FDG uptake at the sternal end of the left clavicle (SUVmax 9.3). C – Hypermetabolic inguinal lymph nodes, predominantly on the right side (SUVmax 10). D – Hypermetabolic lymph node in the left parotid space (SUVmax 8.3)

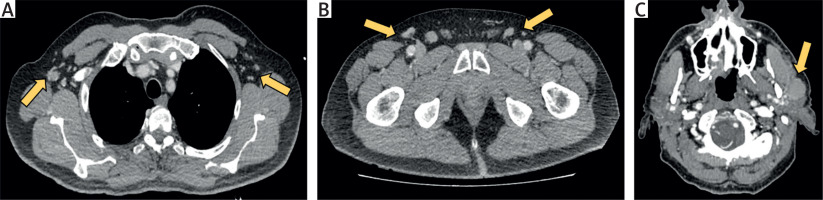

Figure 4

Computed tomography images illustrating pathologically enlarged lymph nodes in various regions. A – Axillary lymph nodes, with the largest measuring up to 12 mm. B – Inguinal lymph nodes, with enlargement up to 13 mm. C – Intraparotid lymph node measuring up to 30 mm

The patient was subsequently started on chemotherapy. The chosen chemotherapy regimen was the R-CHOP protocol, which combines the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin (hydroxydaunorubicin), vincristine (oncovin), and prednisone. Six cycles of chemotherapy resulted in significant regression of the paravertebral mass and an improvement in symptoms. Follow-up imaging demonstrated a notable reduction in the size of the lesion and decreased metabolic activity, underscoring a positive response to treatment.

This case illustrates the complex and challenging nature of diagnosing a tumor in the posterior mediastinum, a region known for its diverse range of potential pathologies. The posterior mediastinum houses critical structures, including the descending aorta, esophagus, thoracic duct, and various nerve roots, which can give rise to – or be affected by – a variety of tumors. The differential diagnosis for a mass in this area is extensive and includes neurogenic tumors, lymphomas, metastatic lesions, and inflammatory conditions such as thoracic peri-aortic fibrosis and IgG4-related disease [4]. The initial approach to a posterior mediastinal mass typically involves imaging studies, such as CT and MRI, to characterize the lesion’s size, location, and relationship to surrounding structures [5]. In our case, the patient presented with persistent left flank pain, and imaging revealed a paraaortic mass extending from T9 to T11, prompting concerns for a neoplastic process. The imaging characteristics of the mass, including its location and relationship to the descending aorta, were crucial in guiding the differential diagnosis.

Neurogenic tumors, such as schwannomas and neurofibromas, are among the most common posterior mediastinal masses and usually present as well-defined, round lesions that may extend through the intervertebral foramina [6, 7]. However, the lack of these imaging features and the mass’s intimate association with the descending aorta made this diagnosis less likely in our case. Thoracic peri-aortic fibrosis and IgG4-related disease were also considered, particularly given the presence of paraaortic tissue. These conditions can present with soft tissue thickening around the aorta and may be associated with systemic manifestations [8]. However, the presence of hypermetabolic activity on PET/CT and the extent of tissue involvement suggested a more aggressive process, warranting further investigation. Lymphoma emerged as a key consideration due to the mass’s characteristics and the absence of other common causes. Lymphomas in the posterior mediastinum can be challenging to diagnose, especially when they present as isolated masses without significant lymphadenopathy. The PET/CT scan provided critical information by revealing increased metabolic activity in the mass, as well as in other lymphoid tissues, supporting the suspicion of a lymphoproliferative disorder. Diagnosing posterior mediastinal tumors can be fraught with pitfalls, particularly when relying solely on imaging. The overlapping features of different entities can lead to diagnostic uncertainty. For example, the distinction between benign neurogenic tumors and malignant lymphomas can be challenging, especially in cases where the tumor exhibits atypical behavior or when small lymphoid infiltrates mimic inflammatory processes [3, 9].

Another significant challenge is obtaining a definitive tissue diagnosis. The posterior mediastinum’s deep location and proximity to vital structures can make biopsy procedures technically difficult and risky. In our case, a fine-needle biopsy of a hypermetabolic lesion in the left parotid gland provided the tissue diagnosis, revealing features consistent with follicular lymphoma, classic type, Grade 1/2 (cFL 1/2). This highlights the importance of considering all available biopsy sites, especially when the primary lesion is difficult to access. This case underlines the complexity of diagnosing tumors in the posterior mediastinum and the importance of a comprehensive approach that integrates clinical, imaging, and histopathological data. The differential diagnosis for posterior mediastinal masses is broad, and distinguishing between different etiologies requires careful consideration of imaging characteristics and tissue pathology. The diagnosis of follicular lymphoma in this case was ultimately made through a combination of advanced imaging techniques and targeted biopsy, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary collaboration in managing such challenging cases. The patient’s favorable response to chemotherapy, with significant regression of the mass and symptom improvement, highlights the importance of timely and accurate diagnosis, which can significantly impact treatment outcomes and prognosis in patients with posterior mediastinal tumors.