Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most frequent form of leukemia in Western countries [1]. Currently, there are three histological and clinical categories of CLL. The typical CLL is an indolent form, while accelerated CLL (A-CLL) and Richter transformation (RT) represent more aggressive forms [2–4].

Diagnosis of accelerated CLL is based on histopathological evaluation of tissue samples and was first reported by Giné et al. [5]. Currently, the A-CLL diagnosis requires at least one of the diagnostic criteria to be met: the presence of expanded proliferation centers (broader than a 20× microscopic field), or a high proliferation rate (either > 2.4 mitotic figures per proliferation center or Ki-67 index > 40% per proliferation center) [5, 6]. It is estimated that A-CLL occurs with a frequency of less than 1% of all CLL cases. However, its incidence is probably underestimated, as tissue biopsy is not usually indicated in the diagnostic work-up of CLL, besides suspicion of RT or small lymphocytic lymphoma [3]. Accelerated CLL is considered to have an aggressive clinical presentation and is often mistaken for RT. It is characterized by rapidly progressive and generalized lymphadenopathy with elevated lactate dehydrogenase and beta-2-microglobulin levels [5]. The role of positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) is still unclear, but a higher standardized uptake value (SUV) has been reported [3]. Accelerated CLL seems to be associated with a poorer prognosis than typical CLL [3]. A higher incidence of the unmutated status of the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region genes (IGHV) and del17p has been associated with acceleration rather than with classical CLL [3, 5, 7, 8]. Unfortunately, no distinctive radiological or laboratory findings are specific for A-CLL. Diagnosis remains a challenge and requires an expert haemato-pathologist [3, 5]. Moreover, the state of knowledge regarding the best therapeutic option is also insufficient.

So far, no complex analysis of A-CLL demographics and treatment outcomes has been performed in substantial groups of patients. Therefore, in this retrospective study, we report the clinical characteristics, treatment methods, and factors impacting the prognosis and outcomes of a large series of individuals diagnosed with A-CLL in Polish hematology centers. Moreover, we aim to evaluate the impact of prior CLL treatment on the time to disease acceleration.

Material and methods

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Institute of Hematology and Transfusion Medicine (No. 19/2024). It was conducted in a multicenter, retrospective form and included patients diagnosed with accelerated CLL between 2013 and 2023 in thirteen Polish Adult Leukemia Study Group hematology centers. The centers were selected based on voluntary cooperation. Identification of patients with A-CLL was guided by the diagnostic criteria established by Giné et al. [5]. Investigators conducted a detailed review of the archival institutional papers and electronic medical records to identify patients with accelerated CLL. In each center, the cases were selected by reviewing histopathology results. Patient data were meticulously gathered, encompassing a comprehensive range of clinical and laboratory information. Detailed CLL and A-CLL diagnosis characteristics were recorded, along with documentation of treatment regimens, treatment response, and subsequent follow-up. For a more thorough analysis, the entire cohort was divided into two groups: treatment-naïve patients (TN), who either experienced disease acceleration at diagnosis or were observed with CLL and later accelerated during follow-up, and relapsed/refractory (RR) patients, who exhibited acceleration after prior CLL treatment. The data were collected using an electronic, anonymized table form. The study was reported following the STROBE guidelines.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the R programming language (version 4.3.3). Statistical significance was defined as a p-value below 0.05. As the analyses were preplanned, no correction for multiple comparisons was applied.

Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, or the Kruskal-Wallis test, while the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of continuous variables. For normally distributed data, two groups were compared using the two-sided independent Student’s t-test; alternatively, the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was employed for non-normally distributed or ordinal variables.

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were compared between the analyzed groups utilizing the Kaplan-Meier estimator and log-rank test. Furthermore, Cox’s proportional hazard models were applied to evaluate the impact of clinical, cytogenetic, and treatment-related factors on survival outcomes. A competing risk analysis was also performed using Gray’s test to compare the competing risk function curves. In comparisons by age group, the patients were divided based on the median age of the sample.

Results

One hundred and six patients with A-CLL were identified between 2013 and 2023, including 2 (1.9%) patients who presented with accelerated small lymphocytic lymphoma (A-SLL). Of the A-SLL patients, one later developed lymphocytosis, but another patient did not experience lymphocytosis during the follow-up. We further analyzed two groups of patients: TN A-CLL and RR A-CLL (Table 1).

Table 1

Patients’ clinicopathological characteristics at the moment of accelerated chronic lymphocytic leukemia diagnosis

A-CLL – accelerated chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CIRS – Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, CLL – chronic lymphocytic leukemia, ECOG – Eastern Cooperative Onco- logy Group, SD – standard deviation, R-CHOP – rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, SLL – small lymphocytic lymphoma

Treatment-naïve patients with accelerated chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Patients’ characteristics

The study enrolled 60 TN A-CLL patients. The group consisted of 21 females and 39 males. Forty-one (68.3%) patients were diagnosed with acceleration at the time of CLL diagnosis. At the time of acceleration, most patients were in good medical condition, with 83.3% of patients having Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 and 1 and a median Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score of 4.5 (range 0–16). The mean age at the time of A-CLL diagnosis was 63.19 (SD 11.97) years. In most cases, disease progression was assessed with CT (31/60 patients). Only 30.0% had PET-CT. Twenty-three patients (41.8%) out of 55 with known data had bulky disease (> 5 cm), and eight patients had extra-nodal localization. The data concerning CLL cytogenetic and molecular risk factors at the time of A-CLL diagnosis included del17p, del11q23, tri12, del13, and TP53 mutation. The TP53 mutation was assessed using the Sanger sequencing method. The del17p was noted in 13.3% (6/45 patients), while TP53 mutation was observed in 25.0% (3/12 patients) of the analyzed cases. Detailed demographic, clinical, and laboratory profiles of the enrolled patients are provided in Table 1.

Survival and prognostic factors

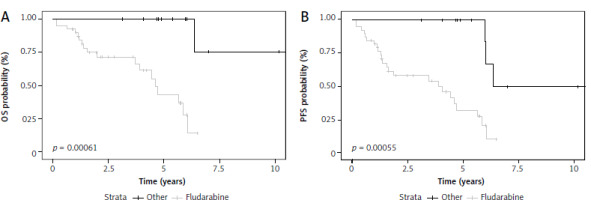

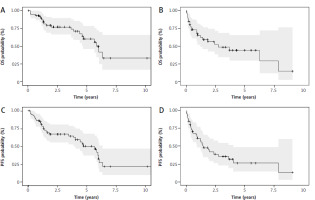

The median follow-up time after acceleration was 2.5 years (range 0.05–10.70 years). The median PFS in this cohort was 5.66 years (95% CI: 4.05–6.34) (Fig. 1). Death was noted in 22 patients (36.7%) during follow-up. After A-CLL diagnosis for TN patients, the median OS was 6.05 years (95% CI: 4.7–NA) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival for treatment-naive (TN) accelerated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (A-CLL) patients (A) and relapsed/refractory (RR) A-CLL patients (B), progression-free survival for TN A-CLL patients (C) and RR A- CLL patients (D)

OS – overall survival, PFS – progression-free survival

ECOG ≥ 2 at the time of A-CLL diagnosis was associated with worse PFS (HR 6.3, 95% Cl: 2.3–17.2, p < 0.0001) and OS (HR 10.75, 95% Cl: 3.6–32, p < 0.0001). Another factor identified as a predictor of poor PFS in univariate analyses was the presence of del17p. Median PFS in this group of patients was 2.22 years (95% CI: 0.17–NA) vs. 5.96 years (95% CI: 4.7–NA). The presence of del17p at the time of A-CLL significantly increased the risk of progression or death (HR 6.48, 95% Cl: 1.94–21.65, p = 0.002). A summary of clinicopathological factors associated with TN A-CLL patients’ OS and PFS is provided in Supplementary Tables 1, 2.

Patients with relapsed/refractory accelerated chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Patients’ characteristics

Forty-six patients with RR A-CLL were identified in our cohort, including 17 females and 29 males. The mean age at the time of A-CLL diagnosis was 62.37 (SD 9.88) years. The median time from CLL diagnosis to acceleration was 9.19 years (range 0.13–19.17). The median number of lines of CLL therapy before acceleration was 2 (range 1–12). Eighteen patients transformed to accelerated type CLL during treatment: five during immunochemotherapy, two during BCL2 inhibitor monotherapy treatment, and eleven during Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKI) treatment. 69.6% of patients had an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1. The median CIRS score was 5 (range 0–30). Regarding cytogenetic and molecular risk factors, del17p was noted in 34.2% (13/38 patients), while TP53 mutation was reported in 33.3% (5/15 patients) of the analyzed cases. Detailed demographic, clinical, and laboratory profiles of the enrolled patients are provided in Table 1.

Survival and prognostic factors

The median follow-up time after acceleration was 0.99 years (range 0.02–7.87 years). The median PFS in this cohort was 1.46 years (95% CI: 0.92– 4.02) (Fig. 1). The median OS after A-CLL diagnosis for RR CLL patients was 2.74 years (95% CI: 1.22–NA) (Fig. 1). Death was noted in 23 patients (50%) during follow-up.

In this group of patients, the factors identified as predictors of poor OS were male sex (HR 3.1, 95% CI: 1.1–8.5, p = 0.03) and ECOG ≥ 2 at the time of A-CLL diagnosis (HR 2.6, 95% CI: 1.08–6.26, p = 0.03). At the same time, neither these factors nor any others were identified as statistically significant predictors of poor PFS. A summary of clinicopathological factors associated with RR A-CLL patients’ OS and PFS is provided in Supplementary Tables 3, 4.

Among 46 RR A-CLL patients, 18 patients transformed during CLL treatment. Acceleration on treatment proved to be a negative prognostic factor, increasing the risk of progression or death (HR 3.2, 95% CI: 1.45–7.06, p = 0.004). A statistically significant PFS difference between the two groups was noted: patients with acceleration after previous treatment and those with acceleration on treatment (p = 0.003). What is more, previous resistance to fludarabine, reported in 7 patients, proved to be an adverse prognostic factor in the previously treated cohort, increasing the risk of death (HR 5.49, 95% CI: 1.79–16.84, p = 0.003) and the risk of progression or death (HR 4.97, 95% CI: 1.69–14.63, p = 0.004).

Treatment outcomes

In both the TN and RR A-CLL cohorts, the patients were divided into four main groups according to the type of treatment they received. The majority received immunochemotherapy. Twenty-two patients (20.8%) were treated with immunochemotherapy including rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) and R-CHOP-like protocols. Twenty-one (19.8%) received the bendamustine-rituximab (BR) protocol. Seventeen patients (16.0%) received fludarabine-based immunochemotherapy. Finally, 23 patients were treated with targeted therapy. This group included BTKI monotherapy (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, a single patient received TL-895) and venetoclax-based regimens (obinutuzumab-venetoclax, rituximab-venetoclax, and venetoclax monotherapy). Nine patients were not treated, as they did not meet the criteria for initiating CLL treatment according to the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (iwCLL) [2]. Others were treated with different protocols, e.g., obinutuzumab-chlorambucil, rituximab-chlorambucil, high-dose methylprednisolone monotherapy, or a clinical trial, and were not included in further analysis.

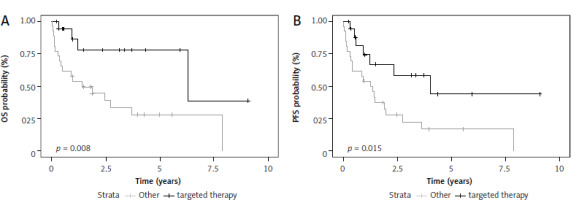

Treatment-naïve patients with accelerated chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Fludarabine-based therapy regimens as first-line treatment of TN acceleration patients were associated with better OS (HR 0.062, 95% Cl: 0.008–0.48, p = 0.008) and PFS (HR 0.15, 95% Cl: 0.04–0.5 p = 0.002) (Fig. 2). There was no statistically significant impact on OS or PFS in patients treated with targeted therapy in the front-line setting. However, this group consisted of only four patients. When used as a subsequent line of treatment, novel agents were associated with significantly better OS (p = 0.045).\

Patients with relapsed/refractory accelerated chronic lymphocytic leukemia

In the group of RR A-CLL patients, targeted therapy was associated with significantly longer OS (HR 0.25, 95% Cl: 0.08–0.75, p = 0.01) and PFS (HR 0.36, 95% Cl: 0.15–0.85, p = 0.02) as compared to other therapies (Fig. 3). This trend was also observed for OS when targeted agents were used as any line of therapy (HR 0.28, 95% CI: 0.12–0.68). There was no statistically significant difference between fludarabine or bendamustine-based regimens in this group of patients. Interestingly, patients with relapsed or refractory A-CLL who were treated with R-CHOP-like protocols in the first-line setting had worse OS than A-CLL patients who did not receive such treatment (HR 2.56, 95% CI: 1.08–6.1, p = 0.033).

Prognostic factors and treatment outcomes in the whole group of patients with accelerated chronic lymphocytic leukemia

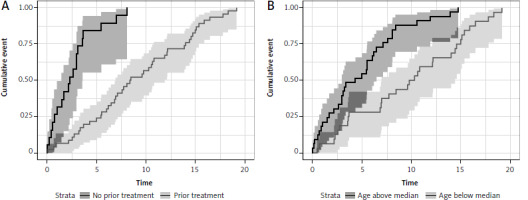

In patients previously diagnosed with CLL (both TN and RR), treatment prolonged the time of occurrence of acceleration (p < 0.0001), with a statistically significant 83% reduction of the risk of acceleration (HR 0.16, 95% CI: 0.08–0.31, p < 0.0001). The 5-year cumulative incidence was 84% (95% CI: 55–95) in untreated and 24% (95% CI: 13–37) in the previously treated group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Another factor affecting the survival was age below the median at the time of CLL diagnosis. Younger CLL patients had a statistically significantly longer time to acceleration (p < 0.0001) with every year increasing the risk of shorter time to acceleration (HR 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03–1.08, p < 0.0001). The 5-year cumulative incidence of acceleration was 55% (95% CI: 36–70) in the above-median age group vs. 28% (95% CI: 14–44) in the below-median age group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Time to diagnosis of accelerated chronic lymphocytic leukemia in regard to previous treatment (A) and patient age (B)

In the whole analyzed group, fludarabine-based therapy regimens in front-line treatment of acceleration were associated with better prognosis in OS (HR 0.17, 95% CI: 0.05–0.57, p = 0.004; log rank test p = 0.001) and PFS (HR 0.26, 95% CI: 0.11–0.61, p = 0.002; log rank test p = 0.001). In a further analysis of the whole group, fludarabine-based regimens proved to be superior to bendamustine-based regimens in OS (p = 0.007) and PFS (p = 0.001); and to R-CHOP-like protocols in both OS (p = 0.004) and PFS (p = 0.003). There was no statistically significant difference in OS and PFS between fludarabine-based regimens and targeted therapy or in any other performed comparisons. However, the group of patients treated with new therapies was very heterogeneous. It should be noted that patients in whom fludarabine-based regimens were used as first-line treatment of acceleration were statistically significantly younger than patients treated with R-CHOP-like protocols (mean age 55.15 vs. 62.4 years, p = 0.02). There were no statistically significant differences between these groups in ECOG or the number of previous lines of CLL treatment.

Administering fludarabine in any line of treatment during acceleration was associated with a reduced risk of death (HR 0.18, 95% CI: 0.06–0.54, p = 0.002). Similarly, administering targeted therapy in any line of acceleration treatment significantly reduced the risk of death (HR 0.48, 95% CI: 0.25–0.92, p = 0.03). Conversely, using R-CHOP-like or bendamustine-based regimens did not demonstrate any statistically significant effects on overall survival.

Discussion

This study represents the largest series of biopsy-confirmed accelerated CLL patients with an extended follow-up in Poland. A comparable cohort of 117 individuals was described by Falchi et al. in 2014 [9]. However, their study focused on correlating 2-deoxy-2-[(18)F]fluoroglucose/positron emission tomography (FDG/PET) data, histological diagnosis, clinical characteristics, and survival outcomes in patients with CLL, histologically aggressive CLL (HAC) and RT. While the study discriminated HAC, it did not provide a clear definition or its diagnostic criteria.

An earlier study by Giné et al. was one of the first to attempt a clinicopathological characterization of A-CLL patients and to propose diagnostic criteria for the condition. However, their A-CLL cohort consisted of only 23 patients [5]. In terms of treatment outcomes, several case reports documented the efficacy of ibrutinib [10, 11], acalabrutinib [12], and rituximab-venetoclax regimens [13]. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, this study is among the first to explore the clinical characteristics of A-CLL and evaluate the factors affecting survival and treatment outcomes.

Median OS for TN A-CLL patients was 6.05 years compared to 2.74 years for RR A-CLL patients. Considering our recently published data, it seems that the prognosis of RT is poorer. However, no matched-adjusted comparisons were performed. Specifically, for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)-RT patients, the median OS was 17.3 months, as reported in our previous study [14]. Similar observations were reported by Falchi et al., with a median survival of 17.6 months following diagnosis of HAC [9]. The median OS for typical CLL ranges from over 10 to 6.5 years, depending on the stage according to the Rai classification [4, 15]. Our study showed that A-CLL has a poorer prognosis than typical CLL but better than that of RT. However, it is important to note that we did not perform a case-matched comparison.

Comparing this study with other cohorts is challenging, as it mainly included cases suspected of RT and, as mentioned, the definition of HAC used may not align precisely with the definition of A-CLL proposed by Giné et al. [5]. Nevertheless, the OS of our RR A-CLL cohort was 2.74 years, confirming the results of Falchi et al., who found that the prognoses for these cases were better than those for RT but worse than those for typical CLL patients [9]. Interestingly, in their study, HAC and RT patients were characterized by similar PET-CT, and clinicopathological characteristics and were treated with similar regimens. This underscores the importance of verifying the diagnosis when RT is suspected, as the two groups of patients may benefit from different treatment strategies.

Acceleration of CLL is primarily a histopathological diagnosis. Based on the data from the study by Falchi et al., histopathological examination is crucial, as fine-needle aspirations (FNAs) are not sufficiently accurate for diagnosing A-CLL. A comparative analysis of FNAs and tissue biopsies in patients with HAC showed that in 29% of cases, FNAs underestimated the diagnosis [9]. However, the International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms does not provide morphological guidelines for assessing CLL cases with clinical suspicion of disease acceleration [16]. Therefore, this more aggressive type of CLL has been rarely reported or often not included in clinical trials on treatment outcomes.

In our series of patients, most individuals were treated with immunochemotherapy. Although our group was heterogeneous, some interesting differences among various treatment regimens emerged. Our data suggest that fludarabine-based regimens were associated with better outcomes compared to bendamustine-based protocols or R-CHOP therapy. Moreover, R-CHOP-like protocols appeared to be associated with a worse prognosis than other immunochemotherapy protocols, suggesting that their use in A-CLL treatment should be limited.

Twenty-three patients in our study were treated with novel agents. However, this group was highly heterogeneous, with treatments including both BTKIs and venetoclax, either in monotherapy or in combination with rituximab or obinutuzumab. Thus, the comparison of treatment outcomes between immunochemotherapy and novel agents may be biased. There was no statistically significant difference in OS or PFS between fludarabine-based regimens and targeted therapy. It is important to note that CLL-targeted therapies have been widely reimbursed in Poland since 2020. Initially, they were available only as a second-line treatment or for unfit patients, and since 2022, they have been offered as a first-line treatment. Consequently, targeted therapies were unavailable to most patients diagnosed between 2013 and 2020, especially TN patients.

Our study has several limitations. It has a retrospective and multi-center design, and the histopathological diagnosis of A-CLL was not centralized but assessed across different centers. Data on del17p and especially TP53 mutation are scarce and should be addressed in future studies regarding A-CLL. TP53 mutation testing and immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) analysis were not widely available in Poland until 2020–2021. As a result, these data are missing for most patients diagnosed during 2013–2022. Moreover, available treatment options in Poland for patients with CLL across 2013–2022 were changing, and therapies used in the analyzed group of patients are significantly heterogeneous.

Conclusions

Our study represents one of the largest datasets of A-CLL patients and confirms that, while A-CLL has a worse prognosis than typical CLL, its prognosis is better than that observed in RT. Targeted therapies should be considered a treatment modality for A-CLL; however, fludarabine-based regimens have also proven effective in this patient population. It should be stressed that worse outcomes were observed with R-CHOP-like protocols, suggesting that they should not be recommended for A-CLL treatment. These findings need to be validated in prospective investigations, which could aid in the development of guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of A-CLL.