Introduction

Adenosarcoma is a rare neoplasm with a mixed histological structure, including benign epithelial and malignant stromal components [1, 2]. Only close to 1% of all malignant neoplasms of the female reproductive system are adenosarcomas [3]. They are most commonly located in the uterine corpus, less often in the ovaries, and only 2% of cases are in the uterine cervix [4]. A hypothesis has even been proposed that adenosarcoma may grow based on long-standing endometriosis [5]. Cervical adenosarcoma most often affects women of reproductive age. Usually, patients present with abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, or abdominal mass [3, 4, 6]. There are no clear guidelines for treatment. The most common approach is mainly based on hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO). Radiotherapy or chemotherapy is rarely used; they are considered in case of possible disease relapse or advanced International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage. Generally, the prognosis is relatively good, among other things, because it is detected in the earlier FIGO stage than other locations, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 63–84% [3, 4, 6, 7].

In the present study, we have presented the case of a patient with a diagnosis of uterine cervix adenosarcoma. The aim is to share our experience with this neoplasm and, given the lack of treatment guidelines, we also conducted a literature review to better understand the problem.

Case report

A 44-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with a diagnosis of uterine cervical adenosarcoma. Her medical history included three caesarean sections and a diagnosis of endometriosis. She did not take any medications and underwent surgery to remove an endometriosis lesion from a caesarean section scar. The patient had a family history of breast cancer involving her maternal aunt and underwent regular breast ultrasound screening, with the most recent examination classified as BI-RADS 1.

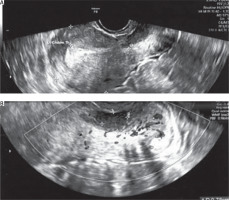

She suffered from abnormal vaginal bleeding for eight months, occurring 7–10 days before her menstruation and lasting 2–3 days, with no other complaints such as pelvic pain or vaginal discharge. During a gynaecological examination with a speculum, a lesion protruding from the cervical canal was observed. A transvaginal ultrasound showed a cervical tumour measuring 25 × 21 × 32 mm. Two months earlier, a Pap smear taken during a routine check-up did not indicate the presence of cancer cells. A test for high-risk oncogenic HPV was negative (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Picture from the TV ultrasound. A) Uterine body with a visible lesion in the cervix. B) Lesion visible at closer zoom at greater magnification

A biopsy of the lesion confirmed the presence of low-grade adenosarcoma of the cervix. Immunohistochemistry showed the following results: CK 8/18 (–), CK5/6 (–), CK7 (–), p63 (–), SMA (–/+), desmin (–/+), caldesmon (–/+), MyoD1 (–), myogenin (–), p53 wild type; p16 (–), CD10 (–/+), ER (–/+), Ki-67 – 10%. A magnetic resonance imaging was performed, showing that the lesion did not exceed the wall of the cervix, and no pathologically enlarged lymph nodes were visible. A computed tomography scan of the lungs and abdomen ruled out any signs of distant disease. Based on this information, the patient was deemed suitable for surgical treatment. A radical hysterectomy (RH) with BSO and pelvic lymph node sampling was performed.

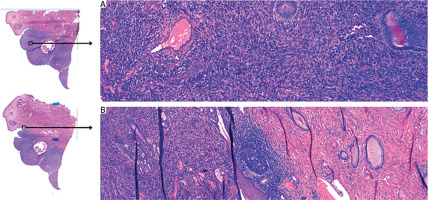

The pathological results confirmed a low-grade adenosarcoma. Macroscopic examination of the specimen revealed a 3 cm long cervix, a 4.5 × 4 cm area with “erosion” in the external opening, with a whitish infiltration reaching the ectocervix and in the area of the internal opening. Body of the uterus: 6.5 × 5 × 6.5 cm. Endometrium was macroscopically normal, 3 mm in thickness, with a slit-like cavity. The cervical tumour macroscopically did not invade the body of the uterus. Microscopic examination results showed the neoplastic tissue found in the vaginal portion of the cervix and cervical canal. Maximum depth of stromal invasion was assessed as 15 mm, maximum lesion size – about 25 mm. The minimum radial margin in the cervical canal was 7 mm. The minimum excision margin from the vagina was 11 mm. The cervical surface was covered with normal paraepidermoid epithelium. The endometrium was in the secretory phase, and traces of adenomyosis were found. The parametrium was free from any neoplastic infiltration. Both ovaries and fallopian tubes were found to be of normal histological structure. Sampled, enlarged lymph nodes were assessed, and no cancer metastases were detected. The neoplasm was classified as stage: pT1b1N0, FIGO IB2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Microscopic examination. A) The histopathological analysis reveals glandular structures lined by metaplastic mucinous epithelium, lacking cellular atypia or mitotic activity. Additionally, the stromal component consists of spindle cells organized in sheet-like arrangements. B) The borderline between healthy and cancerous tissue

The patient was discharged home in good overall condition. No additional therapy was undertaken. A “watch and wait” strategy to monitor the patient was adopted. A gynaecological examination with TV ultrasound was recommended every 3–6 months for the first 2 years, then every 6–12 months for the following 3–5 years. The last follow-up for the patient was in March 2025. The patient reports feeling free from any symptoms. The gynaecological examination and TV ultrasound showed no signs of recurrence or abnormalities in the lower pelvis. A computed tomography scan of the chest and abdomen was also performed, which showed no metastasis or recurrence.

Discussion

In our paper, we want to introduce and analyse the data on cervical adenosarcoma. Due to its rarity, we are missing clear guidelines for the management and surveillance of the disease.

Epidemiological data

Sarcomas of the uterus constitute 2–4% of the malignant tumours of this organ, of which 5% are adenosarcomas. They account for only 1% of all malignant tumours of the female reproductive organs, and up to 3% of all uterine tumours. Adenosarcomas most often are located in the uterine corpus, up to 71% of cases, then in the ovaries (up to 12%), and only up to 2% occur in the cervix [6, 8]. However, its occurrence outside the uterus has also been documented, including the vagina, fallopian tube, retroperitoneum, and urinary bladder [3]. The median age of occurrence of cervical adenosarcoma is 37–39 years, nevertheless, there are also described cases of very young or older women. Usually, patients are referred to a gynaecologist due to abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, or abdominal mass [3, 4, 6]. High-risk factors include obesity, history of pelvic radiotherapy, overload or imbalance of estrogen (ER), and use of oral contraceptives or tamoxifen for an extended period [9]. Although HPV is a decisive risk factor for developing cervical cancer, no correlation has been proven in the context of adenosarcoma. Generally, the prognosis is relatively good, mainly because it is detected in the earlier FIGO stages than other locations, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 63–84% [3, 4, 6, 7]. However, the factor that worsens the prognosis is sarcomatous overgrowth (SO, sarcomatous component occupying more than 25% of the tumour volume), which increases the risk of recurrences to 45–70%. Moreover, the poor prognosis also depends on deep myometrial invasion, presence of heterologous elements, lymphovascular invasion, tumour necrosis, mitotic rate, and initial tumour size [3, 10, 11].

Pathology

The procedure for making a diagnosis is similar to that for other malignant cervical cancers. The differential diagnosis of adenosarcoma includes adenofibroma, carcinosarcoma, endocervical polyp, endometrial stromal sarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. The diagnosis depends on, among other things, high mitotic activity (> 1 per 10 high-power fields); this way, you can distinguish adenosarcoma from adenofibroma, for example [4].

Histological characteristics of cervical adenosarcoma include irregular glands with pronounced branching, often resembling the architectural pattern seen in phyllodes tumours of the breast. The periglandular stroma is cellular, well-demarcated, and closely follows the glandular epithelium. Additional features include stromal mitotic activity, varying degrees of stromal cell atypia, and an epithelial lining that frequently, though not always, exhibits altered differentiation, most commonly presenting as ciliated or endometrioid-like epithelium [2, 12].

Immunohistochemistry is not essential for diagnosis; however, low-grade adenosarcomas typically exhibit positivity for CD10 and hormone receptors. Their mesenchymal component shares immunohistochemical features with endometrial mesenchymal sarcomas. Aberrant p53 expression is observed in the overgrown sarcomatous areas, with the mesenchymal elements displaying similarities to high-grade uterine sarcomas, characterized by an elevated Ki-67 proliferation index [9].

This tumour’s molecular profile lacks specific gene mutations or characteristic chromosomal alterations. However, some cases show 8q13 amplification and an increased MYBL1 copy number, particularly in association with SO, while NCOA2/3 gene fusions are less commonly detected. Studies have demonstrated that high-grade adenosarcoma frequently exhibits TP53 pathway alterations, contributing to its aggressive clinical behaviour [13]. A recent study analysed 29 adenosarcoma cases, examining 40 commonly mutated genes using whole-genome sequencing and next-generation sequencing validation. The results indicated that KMT2C and BCOR mutations were frequently present in both SO-associated and non-SO cases, whereas MAGEC1 and KDM6B mutations were strongly linked to SO. Furthermore, the frequency of gene mutations in adenosarcoma with SO was approximately 33%, significantly higher than the 11% observed in cases without SO [9, 13, 14].

There is a possibility of an association between adenosarcoma and long-standing endometriosis. Malignancy arising from endometriosis is a rare occurrence, affecting fewer than 1% of cases. When it does occur, the most frequently observed cancer types include endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma. Additionally, there have been occasional reports of adenosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma developing from endometriotic tissue [15]. However, the development of sarcoma from endometriosis is controversial. Palicelli et al. described primary malignant endometriosis-associated tumours arising from the episiotomy site and did not find any sarcoma, melanoma, or malignant trophoblastic tumours [16]. While the etiopathology of endometriosis-related carcinogenesis remains incompletely understood, it is posited that DNA damage may arise from oxidative stress associated with menstruation [17]. This correlation is more strongly evidenced in extrauterine sites, however, there are isolated indications that similar occurrences may also take place within the uterus [18, 19]. It can be suggested that this is a positive risk factor because the symptoms experienced by patients with endometriosis cause them to visit a doctor more often, and the chance of detecting the cancer earlier increases. This is better known for ovarian cancer based on endometriosis, but it cannot be ruled out that this also applies to the cervix adenosarcoma [20, 21]. One of the contributing factors to malignant transformation is exposure to unopposed ER [22]. Prolonged stimulation by ER without the balancing effect of progesterone (PR) can lead to endometrial hyperplasia, atypical cellular changes, and eventually malignancy [15, 23]. However, such reports have not been reported yet for adenosarcoma of the uterine cervix. Nevertheless, this topic is not fully understood and requires further research. Moreover, given the rare but serious risk of malignant transformation, individuals with a history of endometriosis require closer surveillance compared to the general population. When a new mass is identified, clinicians should consider the potential for cancer arising from endometriotic tissue [15, 23].

Diagnosis

The basic screening test for cervical cancer is cervical cytology. However, our patient had a normal cervical cytology result, but this is not an isolated case; previously described cases also did not show the presence of malignant cells in the cervical smears [4, 5]. For this reason, it can be concluded that there are no screening tests for this neoplasm [24]. In this case, it is essential to maintain oncological vigilance and perform additional tests such as abrasion, hysteroscopy, or tumour biopsy. Magnetic resonance imaging or positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) is mainly used for imaging of cervical adenosarcoma. Magnetic resonance imaging, including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences, plays a key role in the preoperative evaluation of cervical adenosarcoma, helping to differentiate it from other tumours and to assess the degree of invasion and the presence of a SO component. Typically, the tumour may present as a polypoid mass in the cervical canal with low signal on T1-weighted sequences (T1WI) and mixed high signal on T2-weighted sequences (T2WI). In some cases, there is uneven contrast enhancement and a lack of diffusion restriction on DWI images, which may indicate a less aggressive nature of the tumour. DWI is mainly used in the evaluation of cervical adenosarcoma, especially in identifying the SO component. High signal intensity on DWI may suggest the presence of more aggressive tumour tissue. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucos may be helpful in the evaluation of lymph node metastases and treatment planning. However, because of the rarity of cervical adenosarcoma, data on the efficacy of PET/CT in this specific location are limited [25].

Therapeutic options

Due to its rarity, there are no clear treatment guidelines for cervical adenosarcoma. Since uterine adenosarcoma is a more common variant, many specialists suggest methods of its treatment. Surgical treatment is the option of choice; in selected cases, it is supplemented with adjuvant therapy, i.e., radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or hormone therapy [2, 4, 9]. The most common procedure is total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) +/– BSO, although RH + BSO is also performed. The extended approach of surgery may depend on the stage of the tumour, the presence of SO, or deep myometrial invasion. It is not systematically recommended to remove lymph nodes, though resection of bulky nodes is mandatory [9, 11]. In our case, we performed sampling of suspicious pelvic lymph nodes, but they were negative. Adenosarcoma of the uterine cervix is most frequently diagnosed in premenopausal women. There is currently insufficient evidence to suggest that bilateral oophorectomy confers a survival benefit in premenopausal patients with stage I low-grade uterine adenosarcoma. In highly selected cases of young women presenting with stage IA low-grade tumours without sarcomatous overgrowth, fertility-sparing approaches may be appropriately considered [26]. While minimally invasive, fertility-preserving treatment may be an option for low-grade, early-stage tumours, it remains a subject of debate due to concerns about recurrence. If this approach is pursued, close monitoring through regular examinations and imaging is essential for early detection of recurrence. Opponents of fertility preservation argue that the increased risk of recurrence poses a significant concern [5, 14, 27].

Adjuvant therapy includes radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or hormone therapy. Hormonal therapies have been explored in the treatment of Müllerian adenosarcomas due to the frequent expression of ER and PR. Studies indicate that ER and PR positivity is observed in about 50–80% of these tumours [11]. Studies have evaluated various hormonal therapies in patients with uterine adenosarcoma, including gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists like leuprolide, synthetic progestins, aromatase inhibitors, and selective ER modulators. Despite their different mechanisms of action, these therapies function by reducing ER levels or blocking its effects. Research indicates that most patients with adenosarcoma of the uterine corpus or cervix derive little benefit from hormonal treatment [5, 28]. Regarding radiotherapy, most retrospective studies have not shown a survival benefit; it is recommended more in cases of cancer recurrence. However, Bernard et al. in their publication suggest that patients with adenosarcoma + SO and myometrial invasion should be considered for at least adjuvant radiotherapy to the pelvis [29]. Chemotherapy is based on the administration of doxorubicin- based, platinum-based, trabectedin, or gemcitabine regimens. Among chemotherapy regimens, doxorubicin combined with ifosfamide has demonstrated superior progression-free survival compared to alternative treatments. Most data pertain to metastatic or recurrent adenosarcoma of the uterine corpus rather than localized disease or cervical adenosarcoma [5, 30].

In summary, adjuvant therapy is typically not advised; however, it may be considered for patients with myometrial invasion, sarcomatous overgrowth, or a high risk of recurrence [5].

Conclusions

Adenosarcoma is a sporadic neoplasm, and the cervix is a unique location. Most patients with adenosarcoma are in the early stages of the disease, which significantly improves the prognosis. Although there are no official recommendations for the treatment of this neoplasm, the literature suggests that the most appropriate treatment is TAH + BSO without adjuvant therapy in cases of low risk for recurrence. More research is needed on a more significant number of cases, perhaps due to the rarity of multi-centre studies.