Introduction

Despite significant advances in cancer diagnosis and treatment, current prevention, early detection, and therapeutic strategies have not been fully utilized or realized, and remain insufficient to effectively reduce cancer incidence and mortality worldwide [1]. This ongoing challenge drives scientists to continually improve and innovate existing methods for cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis [2]. Cancer is characterized by the uncontrolled division of cells, where mutated cells proliferate rapidly and evade natural cell death mechanisms [3]. Classical methods, such as radiotherapy, surgery, and chemotherapy, are widely used for tumor detection and treatment; however, they often fail to accurately detect cancer in its early stages and are associated with various unwanted side effects. According to a survey, approximately 9.6 million people die from cancer each year, and this number is predicted to rise to 13.1 million by 2030 if current trends persist [4].

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) are nanosized materials (typically 5–150 nm) exhibiting ferromagnetic, ferrimagnetic, or superparamagnetic properties. These enable precise control over their delivery to target organs via an external magnetic field. Among MNPs, iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) are the most widely used in biomedicine. Based on molecular structure and iron oxidation state, the three common forms of IONPs correspond to natural iron oxide minerals: magnetite (Fe3O4), maghemite (γ-Fe2O3), and hematite (α-Fe2O3). Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 are particularly prevalent in diagnostics (e.g., as contrast agents) and therapeutic applications, including magnetic hyperthermia, targeted drug delivery, and tumor sensitization [5, 6].

Toxicity and clearance kinetics

The potential of superparamagnetic iron-oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) is ultimately dictated by their biocompatibility and clearance kinetics, as rapid recognition by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) can curtail circulation half-life and provoke dose-limiting toxicities, with uptake efficiency influenced by physicochemical determinants such as size (20–50 nm particles cleared faster than 100 nm analogs), shape (rods exhibiting higher macrophage association than spheres of equal volume), and surface chemistry (neutral or slightly negative ζ-potentials [–10 to 0 mV] reducing opsonization relative to cationic surfaces > +20 mV), while coating strategies such as PEGylation, dextran coronas, silica shells, or zwitterionic polymers enhance colloidal stability and suppress protein corona formation, thus extending systemic circulation [7–9].

Administration routes also impact biodistribution and toxicity – intravenous injection subjects SPIONs to serum proteins and MPS filtration, inhalation promotes pulmonary retention, and topical application limits systemic exposure while enhancing skin penetration [10].

Cytotoxicity mechanisms include oxidative stress via the Fenton reaction and NADPH oxidase activation (ROS, lipid peroxidation, DNA damage), membrane disruption by electrostatic interactions, mitochondrial depolarization ↓ATP, caspase-3 activation), and pro-inflammatory cytokine release (TNF-α, IL-6), with uncoated SPIONs producing 2–4 times higher ROS levels than polymer-coated analogues [11]. Long-term exposure may cause iron accumulation in liver Kupffer cells and splenic red-pulp macrophages, leading to ferritin upregulation and potential fibrosis beyond 30 days [12].

Mitigation strategies encompass surface engineering (PEG, chitosan, zwitterionic brushes reducing protein adsorption > 80%), use of biodegradable cores (e.g., Fe3O4@SiO2 with enzymatically cleavable linkers) to enable renal and hepatobiliary clearance, and active targeting (e.g., RGD peptides or anti-HER2 scFv) to enhance tumor accumulation while minimizing off-target effects, with standardized toxicity and performance assays (e.g., MTT/WST-1, DCF-DA ROS, γ-H2AX, hemocompatibility) recommended alongside comprehensive particle characterization including size, ζ-potential, and relaxivity (r2) [13] (Table 1).

Table 1

Factors influencing iron oxide nanoparticle cytotoxicity [14]

| Factor | Biological impact | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Smaller sizes increase cellular uptake, potentially causing toxicity | [15] |

| Surface chemistry | Uncoated surfaces trigger immune responses | [16] |

| Dose/exposure | High doses or prolonged exposure induce stress | [17] |

| Composition | Metal cores (e.g., Fe, Co) may release toxic ions | [18] |

| Aggregation | Aggregates disrupt cellular function | [19] |

The scientific community acknowledges the urgent need for early-stage cancer diagnosis and treatment, which has led to a surge in the development of new drugs and innovative therapies. Nanotechnology is now being employed to create new materials with the potential for precise and accurate cancer detection and treatment, a field known as nano-oncology [20, 21]. Nanotechnology has been integrated with various other technologies, such as optical technology and molecular biology, to develop new toolkits for cancer imaging and treatment [22].

Nanotechnology, often described as the science of small, involves the study and manipulation of materials that have at least one dimension in the nanoscale range (1–100 nm) [23, 24]. Various approaches, including physical, biological, and chemical methods, are used to develop nanomedicines. However, significant efforts are being made to develop nanoparticles that are eco-friendly, biocompatible, and biodegradable. There have been reports of nanomaterial synthesis using bio-chemical methods, also known as green nanotechnology, which demonstrate low toxicity to blood cells and effectiveness against bacterial strains, parasites, and cancer cell lines [25].

The first nanoparticle-based drug approved by the USA Food and Drug Administration was Doxil (liposomal doxorubicin) [26]. This approval, granted about two decades ago, came approximately 30 years after the first publication on liposomes in the mid-1960s. In the past five decades, substantial progress has been made in research and clinical nanomedicines [27]. According to ClinicalTrials.gov, at the time of writing, there are around 700 nanomedicines under trial.

In the realm of fundamental research, the discovery of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect has been pivotal in the development of nanosystems [28, 29]. However, challenges such as heterogeneity and susceptibility of these systems remain, impacting their effectiveness [30]. Cancer heterogeneity, which promotes the development of the tumor microenvironment (TME), has provided insights into the effects of nanomedicine on tumors [31]. It has been established that active tumor targeting, leading to nanomedicine accumulation at the tumor site, is a more effective approach compared to traditional therapies [32, 33]. The size, shape, and physicochemical properties of nanoparticles significantly influence their therapeutic properties, laying the foundation for nano-theranostics – the use of nanoparticles as both diagnostic and therapeutic agents [34]. The stimulation of the immune system and nano-bio-catalysis are also highlighted as promising strategies for cancer and tumor inhibition [35–37]. Results from currently developed nano-theranostics have provided direction for the development of more effective nanomedicines in the future [28, 38, 39].

Despite the challenges associated with the interaction of nanomedicines with tumors, they are proving to be promising candidates for cancer treatment. Current studies indicate that the uptake rate of nanoparticles by tumors is only 0.7% of the injected dose, increasing to 0.9% when the nanoparticle surface is ligand-modified [40, 41]. Nevertheless, nanotechnology has made considerable breakthroughs in cancer treatment, showing promising results when used as chemotherapeutic agents and for hyperthermal applications [42–44]. New discoveries are being made in the development of multifunctional nanomaterials that can be used for both diagnosis and treatment, including the introduction of smart nanomaterials that use various targeting approaches when introduced to tumors [45–49]. Nanoparticles are also being tagged with antibodies to achieve target specificity, with minimal effects on normal or healthy blood cells [50–52].

The aim of this review was to compile comprehensive data on the various methods used to develop nanomaterials, compare their sizes and anticancer efficacy, and explore the strategies employed by researchers to diagnose and treat cancer. This review will serve as a resource for scientists and researchers to generate new ideas for developing materials with better outcomes and lower toxicity.

Synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles

The synthesis of IONPs is a critical factor that determines their physicochemical properties and, consequently, their efficacy in biomedical applications. Several synthesis methods have been developed, each with its advantages and limitations.

Chemical methods

The most commonly employed method for synthesizing IONPs is chemical co-precipitation, where ferrous and ferric salts are precipitated in an alkaline medium to form magnetite (Fe3O4) or maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles [23, 24]. This method is advantageous due to its simplicity and scalability, but it often results in a broad size distribution and requires careful control of reaction conditions to prevent oxidation and agglomeration of the nanoparticles [25]. Moreover, the environmental impact of the byproducts generated during chemical synthesis remains a concern [26] (Table 2).

Table 2

Chemically synthesized nanoparticles

| Type of NPs | Chemical method | Size of NPs [nm] | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeO | Polyol method | 13.8 | Magnetic particle imaging | [53] |

| FeO | Microemulsions | 16 | Biomedical applications | [54] |

| FeO | Thermal decomposition | 2–30 | Magnetic hyperthermia | [55] |

| Au@Cu | Electro-deposition | 30–70 | Electrochemical applications | [56] |

Biological methods

To address the environmental issues associated with chemical synthesis, biological methods using microorganisms or plant extracts have been explored [27, 28]. These methods are considered more environmentally friendly and can produce nanoparticles with a narrower size distribution and higher biocompatibility. However, they often suffer from lower yields and longer reaction times, which may limit their practical application [29, 30] (Table 3).

Physical methods

Physical methods, such as thermal decomposition and microemulsion, offer greater control over particle size and shape, leading to more uniform and monodisperse nanoparticles [61]. However, these methods typically require high temperatures, organic solvents, and surfactants, which can be toxic and complicate the purification process [31] (Tables 4, 5).

Table 4

Synthesis of nanoparticles using physical methods

| Type of NPs | Ball mill type/time | Powder size (initial) [µm] | Final size [nm] | Applications | Characterization | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | Horizontal oscillatory mill/50 h | ≈ 0.6–1 | 30 | Antibacterial | XRD, TEM, SEM, HEBM | [62] |

| ZnFe2O4 | Ultrasonic wave-assisted ball mill/80 h | 60 | 20 | Biomedical | XRD, SEM | [63] |

| Fe3O4 | Planetary ball mill/30 h | 40 | 20.5 | Biomedical | XRD, SEM | [64] |

Table 5

Synthesis of nanoparticles using LASER ablation

| Type of NPs | LASER wavelength [nm] | Ablation duration [min] | Source | LASER source | Final Size | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au | 1062 | 30 | Pure Au plate | Nd-YAG | 30 nm | [65] |

| ZnO | 355 | 40 | Metallic Zn foil | Nd-YAG | 5–19 nm | [66] |

| Ag | 532 | 30 | Metallic Ag foil | Nd-YAG | 2–5 nm | [67] |

| TiO2 | 1064 | 10 | Ti plate | Ytterbium doped Fiber LASER | 5–25 nm | [68] |

Bio-chemical

The bio-chemical method is a hybrid technique, in which precursor salt is introduced to biological extracts, mostly plant-derived. Extracts are prepared using alcohols or water from various plant parts [69, 70], including bark, leaves, flowers, fruits, and/or roots. Alcohol-based extraction typically does not require heating, whereas water-based extraction involves heating to release phytochemicals. After obtaining the extract, the precursor salt is added, and mild heat is applied to produce uniformly distributed nanoparticles. Although this method is more time-consuming than chemical synthesis, it is considerably more environmentally friendly. Table 6 contains various examples of nanoparticles synthesized using the bio-chemical method, the part of plant used for their synthesis, their sizes, and their bio-medical applications.

Table 6

Bio-chemical method mediated synthesis of nanoparticles

| Type of NPs | Part of plant | Name of plant | Size of NPs [nm] | Applications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeO | Flower | Callistemon viminalis | ~21 | Biomedical | [24] |

| CuO | Leaves | Acalypha indica | 26 | Antimicrobial | [71] |

| NiO | Flower | Callistemon viminalis | 16.5 | Biomedical | [23] |

| ZnO | Leaves | Sageretia thea | 15.2 | Biomedical | [72] |

Functionalization and targeting strategies

The effectiveness of IONPs in cancer therapy largely depends on their ability to specifically target tumor cells while minimizing off-target effects. To achieve this, IONPs are often functionalized with various ligands, including antibodies, peptides, and small molecules, that can recognize and bind to tumor-specific antigens or receptors [32].

Core-shell and hybrid magnetic nanoparticles

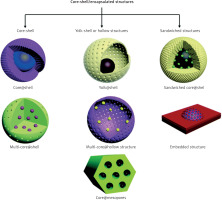

To improve the functionality of MNPs, core-shell structures have been developed, where a magnetic core is surrounded by a shell.

This design improves biocompatibility, dispersibility, and chemical stability while allowing for functionalization with targeted molecules (Figure 1, Table 7).

Table 7

Investigational biomedical applications of various types of magnetic nanoparticles [14]

| Magnetic nanoparticles | Methods of synthesis | Specific diseases targeted | Mechanisms of action | Clinical applications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold-coated MNPs (Fe3O4@Au) | Thermal decomposition, co-precipitation | Glioblastoma, breast cancer | Photothermal ablation via plasmonic heating, targeted drug release | Theranostics targeted drug delivery, and photothermal therapy | [74] |

| Silica-coated MNPs (Fe3O4@SiO2) | Sol-gel method | Liver cancer, brain tumors | Enhanced MRI contrast, controlled drug release via porous structure | Biosensors, drug delivery systems, and enhanced MRI imaging | [75] |

| Polymer-coated MNPs | Co-precipitation, emulsion polymerization | Breast cancer, pancreatic cancer | Magnetic hyperthermia, biocompatible drug encapsulation and release | Controlled drug delivery, biocompatible imaging agents, and hyperthermia | [76] |

| Magnetic nanoclusters (e.g., Fe3O4 clusters) | Thermal decomposition | Solid tumors (e.g., melanoma) | Collective magnetic heating, enhanced MRI sensitivity | Enhanced imaging and hyperthermia due to collective magnetic properties | [77] |

| Cerium-doped iron oxide nanoparticles (Ce-doped Fe3O4) | Hydrothermal synthesis | Osteosarcoma, lung cancer | ROS modulation, radiosensitization via cerium doping | Radiotherapy enhancement and reactive oxygen species (modulation for cancer therapy | [78] |

| Magnetite-gold hybrid nanoparticles (Fe3O4-Au) | Thermal decomposition | Glioblastoma, colorectal cancer | Dual imaging (magnetic and X-ray absorption), photothermal cell destruction | Dual imaging (MRI and X-ray CT), photothermal therapy, and drug delivery | [79] |

| Lanthanide-doped MNPs (Ln-doped Fe3O4) | Solvothermal synthesis | Brain tumors, lymphomas | Luminescent signaling for imaging, magnetic targeting | Luminescence-based bioimaging combined with MRI | [80] |

| Mn-Zn ferrite nanocrystals | Microemulsion | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Magnetically induced hyperthermia targeting cancer cells | Magnetically induced cancer-targeted hyperthermia | [81] |

| Mn-Zn ferrite MNPs | Co-precipitation | Lung cancer, pancreatic cancer | Synergistic hyperthermia and radiosensitization | Enhancing targeted cancer treatment by combining hyperthermia and radiotherapy | [82] |

| Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles (CoFe2O4) | Hydrothermal synthesis | Diabetes, cardiovascular diseases | Magnetic signal amplification for biosensing | Magnetic biosensors for detecting diseases such as diabetes or cardiovascular disorders | [83] |

| Cubic-shaped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles (Co-Fe NCs) | Solvothermal synthesis | Melanoma, breast cancer | High-anisotropy magnetic heating for hyperthermia | Serve as magnetic hyperthermia agents | [84] |

Recent scientific studies have shown promising results regarding the anti-cancer effects of various iron oxide-based nanomaterials

A nanocomposite was effective in targeting and suppressing cancer cell growth using Fe3O4 nanoparticles functionalized with 3-chloropropyl trimethoxy silane and conjugated with 1-((3-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-2-(4-phenylthiazol-2-yl) hydrazine [85].

Iron oxide nanoparticles exhibited a strong potential for inducing apoptosis in HepG2 liver cancer cells, suggesting a promising therapeutic pathway using investigated IONPs coated with glucose and conjugated with Safranal (Fe3O4@Glu-Safranal NPs) [86].

Active targeting

In addition to passive targeting through the EPR effect, active targeting strategies involve conjugating IONPs with ligands that specifically bind to receptors overexpressed on cancer cells, such as folate receptors or HER2 receptors [37]. This approach can significantly improve the specificity of IONPs, leading to higher tumor accumulation and reduced systemic toxicity. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of ligand-functionalized IONPs in enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs, with promising results in preclinical models [38, 39].

Applications in cancer therapy

Iron oxide nanoparticles have been extensively studied for their potential applications in cancer therapy, particularly in the areas of magnetic hyperthermia, drug delivery, and imaging [40, 41].

Magnetic hyperthermia is a therapeutic approach that involves the generation of localized heat by IONPs when exposed to an alternating magnetic field [42]. The heat generated can induce cancer cell death through apoptosis or necrosis, while sparing surrounding healthy tissues [43]. Iron oxide nanoparticles are particularly well suited for this application due to their superparamagnetic properties, which enable them to generate heat efficiently [44, 45]. Several preclinical studies have shown the potential of magnetic hyperthermia to enhance the efficacy of conventional therapies, such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy [46, 47].

Iron oxide nanoparticles can also be used as carriers for chemotherapeutic drugs, enabling targeted delivery and controlled release at the tumor site [48, 49]. The magnetic properties of IONPs allow for their accumulation at specific sites using an external magnetic field, further enhancing their targeting capabilities [50]. This approach has been shown to reduce the systemic toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents and improve their therapeutic index [51]. In addition, the surface of IONPs can be functionalized with stimuli-responsive polymers that release the drug in response to specific triggers, such as pH or temperature changes in the TME [51]. This controlled release mechanism enhances drug efficacy and minimizes off-target effects, which is crucial for reducing the adverse side effects commonly associated with chemotherapy [52, 87].

Iron oxide nanoparticles have also been explored as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), given their strong magnetic properties and ability to enhance image contrast [88]. The superparamagnetic nature of IONPs causes a reduction in the relaxation time of surrounding water protons, leading to enhanced contrast in T2-weighted MRI images [89]. This makes them highly effective in detecting tumors at an early stage, improving the accuracy of cancer diagnosis [90]. In addition to MRI, IONPs have been studied for their potential in other imaging modalities, such as magnetic particle imaging and photoacoustic imaging, which can provide complementary information about tumor location, size, and vascularization [91, 92].

The multifunctional nature of IONPs allows them to be used in combination therapies, where they can simultaneously serve as drug carriers, imaging agents, and hyperthermia inducers [53, 93]. This approach has the potential to improve the therapeutic outcome by targeting multiple pathways involved in tumor growth and resistance, thereby reducing the likelihood of recurrence [54]. For example, recent studies have demonstrated the use of IONPs in combined chemotherapy and hyperthermia, where the heat generated by the nanoparticles enhances the uptake of chemotherapeutic drugs by tumor cells, leading to synergistic effects [55, 56] (Table 8).

Table 8

Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in drug delivery and cancer therapy [14]

| Drug name | Nanoparticle | Targeted cancer | Biological pathway | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acyclovir | Fe3O4 MNPs | Brain cancer | Inhibition of viral replication in tumor cells | [94] |

| Doxorubicin | Gelatin/Fe3O4-alginate | Breast cancer | Induction of apoptosis via DNA intercalation | [95] |

| Doxorubicin | Magnetic iron oxide NPs | Liver cancer | ROS-mediated oxidative stress and apoptosis | [96] |

| Doxorubicin | Iron oxide nanoparticles | Breast cancer | Tumor cell killing via (magnetic hyperthermia and chemotherapy) | [97,98] |

| Erlotinib | Mesoporous MNPs/folic acid | Lung cancer | Inhibition of EGFR signaling pathway | [99] |

| Methotrexate | Chitosan-coated Fe3O4 | Ovarian cancer | Folic acid receptor-mediated endocytosis | [100] |

| Gemcitabine | Fe3O4, metformin, and peptide pHLIP | Pancreatic cancer | Disruption of tumor metabolism and apoptosis | [101] |

| Telmisartan | Fe3O4/chitosan | Prostate cancer | Angiotensin receptor blockade and cell cycle arrest | [102] |

| Chemo/hyperthermia therapy | Tragacanth gum/polycrylic acid/Fe3O4 nanoparticles | Colorectal cancer | Synergistic effect of hyperthermia and chemotherapy | [103] |

| Gene therapy | Fe3O4/polyethyleneimine | Leukemia | Enhanced gene transfection and targeted therapy | [104] |

| Radiation therapy | Au/iron oxide | Various solid tumors | Enhancement of radiation sensitivity through localized hyperthermia | [105] |

| Zidovudine | NiFe2O4/poly (ethylene glycol)/lipid NPs | Lymphoma | Inhibition of viral replication and tumor progression | [106] |

| Doxorubicin | Porous carbon-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles | Melanoma | Heat-induced apoptosis and enhanced drug delivery | [107] |

Challenges and future directions

Despite the promising potential of IONPs in cancer therapy, several challenges remain that need to be addressed to facilitate their clinical translation.

Toxicity and biocompatibility

One of the primary concerns with the use of IONPs is their potential toxicity and long-term biocompatibility [57, 108]. While iron is an essential element in the body, excessive accumulation of iron oxide can lead to oxidative stress and inflammation, particularly in organs such as the liver and spleen [58]. Therefore, careful consideration must be given to the dosage, surface modification, and clearance mechanisms of IONPs to ensure their safety in clinical applications [59].

Targeting efficiency

Achieving efficient and selective targeting of tumor cells remains a significant challenge. Although various targeting ligands have been developed, the heterogeneity of tumor cells and the dynamic nature of the tumor microenvironment can limit the effectiveness of these strategies [60, 109]. Moreover, the formation of a protein corona around the nanoparticles in the bloodstream can hinder their ability to bind to target cells [110]. Ongoing research is focused on developing more sophisticated targeting strategies that can overcome these barriers and enhance the specificity and efficacy of IONPs [111, 112].

Regulatory and manufacturing challenges

The clinical translation of IONPs is also hindered by regulatory and manufacturing challenges [62, 63]. The complex synthesis and functionalization processes involved in the production of IONPs must be standardized and scaled up to meet the stringent requirements of regulatory agencies [64]. Additionally, the lack of established guidelines for the characterization and quality control of IONPs presents a significant hurdle for their approval as therapeutic agents [65].

Future directions

To overcome these challenges, future research should focus on the development of next-generation IONPs with enhanced targeting capabilities, reduced toxicity, and improved stability in biological environments [66, 67]. Advances in nanotechnology, such as the use of biodegradable and stimuli-responsive materials, could pave the way for safer and more effective IONP-based therapies [68, 113]. Furthermore, the integration of IONPs with emerging technologies, such as gene editing and immunotherapy, holds great promise for the development of personalized cancer treatments [114, 115].

Conclusions

Iron oxide nanoparticles represent a powerful tool in the fight against cancer, offering unique opportunities for targeted drug delivery, magnetic hyperthermia, and advanced imaging techniques. While significant progress has been made in the synthesis, functionalization, and application of IONPs, several challenges remain that must be addressed to fully realize their potential in clinical settings [71, 72]. Continued research and collaboration between scientists, clinicians, and regulatory bodies will be essential to overcome these obstacles and develop safe, effective, and widely accessible nanomedicine-based cancer therapies.