Introduction

The anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion gene is one of the driver gene mutations discovered in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients in 2007 [1]. Since this discovery, numerous epidemiological studies have been conducted on the characteristics of ALK fusion gene-positive NSCLC patients, and it is generally accepted that patients with A LK fusion gene-positive NSCLC are more likely to be younger women, non-smokers or light smokers, and have adenocarcinoma, compared to ALK mutation-negative patients [2–5]. However, the median age of patients in clinical trials for ALK-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) appears to be changing, with a median age of early 50s reported in the early 2010s, late 50s in the 2010s, and early 60s reported in the 2020s [6–8]. In addition, several reviews investigated the epidemiological characteristics of a large number of ALK-positive lung cancer patients, considering racial differences [9–13]. In these cases, the median age was initially in the 50s, but recent reports have shown that the median age is now in the 60s [10, 11], with the oldest ALK-mutation-positive patients being 79 [11] and 80 years old [9]. Additionally, while there have been surveys on the percentage of smokers [3–8, 12, 14, 15], few have reported detailed survey results that include smoking intensity [13].

Taking these backgrounds into consideration, we conducted a detailed investigation of the patient background of NSCLC patients with ALK fusion mutations, particularly the distribution of age and smoking intensity. The aim of this study was to re-examine the clinical characteristics of ALK-positive NSCLC patients, particularly regarding age and smoking, so that patients without typical features would not be excluded from ALK testing and efficacious treatment. Although the results were not definitive because this was a retrospective study of approximately 100 ALK-positive NSCLC patients at several facilities, we report some findings that might be useful for future medical practice.

Material and methods

The medical records of all patients with ALK-positive NSCLC diagnosed at 6 medical institutions between May 2012 and November 2024 were retrospectively reviewed. The pathological diagnosis of NSCLC in each patient was performed according to the World Health Organisation classification [16]. Before initiation of anticancer therapy, all patients were staged according to the TNM classification using head computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, bone or positron emission scans, and abdominal ultrasound and/or computed tomography [17]. At the time of NSCLC diagnosis, clinical characteristics, including sex, age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, clinical stage, and the presence or absence of ALK mutations, were investigated. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase mutation was diagnosed by positive results in real-time polymerase chain reaction, immunohistochemistry, or flu- orescence in situ hybridisation, or by a combination of these tests.

In this study, we defined ‘active smokers’ as ‘smokers’. We did not have a clear and common method of describing passive smoking at home or at work, and there were no sufficient medical history records in most patients. Therefore, we defined ‘active smokers’ as ‘smokers’ and did not include passive smokers in ‘smokers’ in this study. The ‘number of cigarettes smoked per day’ and ‘years of smoking (pack-year)’ were also investigated. The product of these indices was used as the smoking intensity [18–20]. Smoking intensity for current smokers and ex-smokers was quantified in terms of pack-years [18–20]. The number of pack-years was calculated by multiplying the number of cigarettes smoked by the number of smoked years and then dividing this total by 20. Light smokers were defined as those who smoked < 20 pack-years, and heavy smokers were defined as those who smoked 20 pack-years or more [18–20].

For statistical analysis in this study, the Mann-Whitney U test, a non-parametric test, was used to compare numbers between the 2 groups, such as age, maximum diameter of primary lesions, and laboratory data. The χ2 test was used to test differences in proportions. A p-value < 0.05 indicated a significant difference.

Results

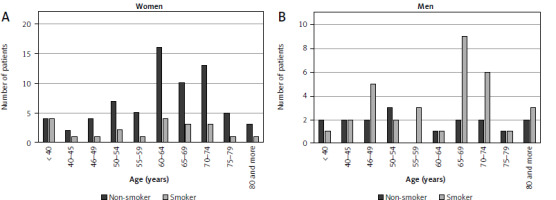

During the study period, the total number of NSCLC patients diagnosed was 4118. Of them, 140 (3.4%) patients were ALK positive. Ninety (64.3%) were women. The median age of all 140 patients was 63 years (range, 26–84 years). The median age of women (63 years; range, 26–83 years) was not significantly different to that of men (65 years; range, 32–84 years; p = 0.950). The age distributions of all patients, and of women and men, are shown in Figure 1. A statistically significant difference was confirmed between women and men (p = 0.004). Table 1 shows a comparison of background factors among female and male patients. The histological type of NSCLC was adenocarcinoma in almost all patients, both men and women. There were no significant differences between men and women in terms of clinical stage and performance status. For smoking history, 54 of the 140 patients (38.6%) had a history of smoking. All the 54 patients were cigarette smokers, and none of them used electric-cigarettes, other tobacco heating systems, or cigars. None of the patients had been exposed to carcinogens such as asbestos or hexavalent chromium in their jobs. The proportion of non-smokers was 76.7% in women and 34% in men, showing a significant difference between sexes (p = 0.001). For smokers, the proportion of patients with less than 20 pack-years of smoking was 71.4% in women, which was significantly different to 39.4% in men (p = 0.028) (Table 1). Table 2 shows the characteristics of patients and ALK-positive lung cancers according to smoking history. Patients with a smoking history had larger primary tumours, lower serum albumin levels, and higher C-reactive protein levels.

Fig. 1

Distribution of patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion gene-positive non-small cell lung cancer according to age. All patients (n = 140) (A), women (n = 90) (B), men (n = 50) (C)

Table 1

Comparison of background factors among women and men in the study

Table 2

Comparison of characteristics in patients with and without a history of smoking in the study

Cytokeratin fragment 19 was significantly higher in patients who smoked, and carcinoembryonic antigen also tended to be higher.

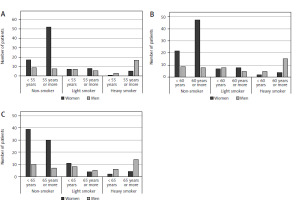

Figure 2 shows the distribution of smokers and non-smokers according to age. No significant differences were found in the age distributions between smokers and non-smokers for women or men (women: p = 0.9113, men: p = 0.6290). Figure 3 shows the age distribution according to sex for different smoking statuses. Comparisons between ages < 55 and ≥ 55 years, < 60 and ≥ 60 years, and < 65 and ≥ 65 years are shown. A significant difference was confirmed between men and women for each of these ages (p = 0.001 for each comparison).

Discussion

In real clinical practice, we sometimes encounter NSCLC patients with ALK mutations who have clinical backgrounds of being male, older, and having a history of heavy smoking. In this study, we investigated the characteristics of ALK-positive NSCLC patients in real clinical practice against this background, and the following 6 points became clear:

64.3% of patients were women,

the median age of all patients was 63 years (range 26–84 years),

38.6% of patients had a history of smoking,

there was a significant difference in the distribution of smokers by sex and age, the proportion of non-smokers among ALK-positive NSCLC patients was significantly different between men and women,

patients with a smoking habit had several clinically unfavourable characteristics such as larger size of the primary lesion, lower serum albumin, and higher C-reactive protein.

Several reviews have been published to date regarding the characteristics of ALK-positive patients, but all of them have presented data of different races, taking into account ethnic differences [12, 13, 21]. In 2014, Fan et al. reported a review based on 1178 patients from 62 studies. Of the 16 studies in which age was specified, the mean age was under 55 years in 5 studies and between 55 and 60 years in 11 studies. In addition, their data showed that 55.6% were women and 29.3% were non-smokers [12]. Zhao et al. presented data on 6950 patients from 27 studies in 2015. The median age of patients in the presented reports was in their 50s. In their collected data, 39.3% were women and 29.3% were non-smokers [21]. In a review published in 2016 by Cadranel et al., the median age of a total of 158 patients was 56 years, 53% were women, and 53% were non-smokers. A notable feature of this study in patients in real clinical practice was their focus on smoking intensity, which, to our knowledge, is the only report to focus on smoking intensity. In their report, the proportions of light and heavy smokers were 22% and 17%, respectively [13]. There were 3 studies in the 2020s related to ALK-TKI treatment. These studies [9–11] investigated 104, 364, and 102 patients, respectively. In the report by Popat et al., the median patient age was 53 years, whereas both Zhang et al. and Goto et al. reported the median age to be in the 60s [9–11]. The proportion of women was 43% and 33.4% in the reports by Popat et al. and Zhang et al., respectively, and the proportion of non-smokers was 47.1% and 49.4%, respectively [9, 10]. Based on these results, the age of affected patients was initially estimated to be early 50s but has since been reported to be late 50s to early 60s [3–11]. The proportion of women in reports ranges 33.4–55.6%, and the proportion of men is not negligible [12, 13, 21]. The proportion of non-smokers ranges 29.3–53%, indicating that the proportion of smokers is also not small [12, 13, 21]. Considering these reports, together with the results of our study, it is clear that ALK-positive NSCLC patients are not limited to women in their 50s who are non- or light smokers. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that limiting ALK testing to patients with these clinical characteristics might narrow the range of patients who could benefit from ALK-TKIs. Another notable finding of this study was that ALK-positive NSCLC patients, especially men, had a history of heavy smoking. Certainly, there is some debate as to whether to perform ALK testing in such patients, considering the “efficiency of testing”, but it seems prudent to wait until further patient data have been accumulated on this point.

In this study, smokers were defined as those who actively smoke. The effects of passive smoking are very interesting. However, we did not include passive smokers in ‘smokers’ because we did not have a clear and common method of describing passive smoking at home or at work, and there was no sufficient medical history record in most patients. It is expected that methods will be established to scientifically quantify the effects of passive smoking and to clarify its relationship to the mechanism of carcinogenesis. Electronic cigarettes were released in our country in November 2014. All smokers in this study were cigarette smokers. Also, none of the patients smoked cigars. Therefore, this study was unable to investigate the effects of passive smoking and tobacco other than cigarettes on ALK-positive NSCLC, and these are considered topics for future research.

The reasons for the ‘gender difference in the effects of smoking in ALK-positive NSCLC’ and the ‘clinically unfavourable characteristics in ALK-positive NSCLC with a history of smoking’ are unknown. Differences in ALK-positive NSCLC itself, differences in the patient background such as comorbidities, or differences in patient response to the development of ALK-positive NSCLC were hypothesised as reasons, but these could not be elucidated in this study. Detailed research on these matters was not within the scope of our knowledge. We believe that future research, including comparisons of responsiveness to treatment and survival time, should be undertaken.

Despite the novel findings above, this study has several limitations. Because this was a multicentre study, the testing methods for ALK mutations were not integrated and patients were included who were diagnosed using several different testing methods. It was not possible to compare information with that of ALK gene mutation-negative patients treated during the same period. In addition, the study period was long because we aimed to recruit a large number of patients. There are limited reports investigating more than 100 patients with ALK-positive NSCLC, so we believe that the information obtained in this study may be useful for the future treatment of NSCLC patients with this mutation.

Conclusions

It is expected that driver gene testing for NSCLC will provide important information for selecting treatments tailored to each patient. Therefore, even among NSCLC patients who are elderly or with a history of smoking, there may be some who miss out on the best possible treatment by exclusion from ALK testing. Discussions considering the efficiency and cost of testing are necessary, and it is imperative to collect and reanalyse as much information as possible about the clinical characteristics of ALK-positive NSCLC patients.