Introduction

Menopause exhibits considerable interpersonal variability, with certain women experiencing its onset prematurely, at an early stage, or later than the usual timeframe [1]. Menopausal age is thought to be a predictor of age-related morbidity and mortality in postmenopausal women [2]. Previous research has found associations between menopause occurring before the age of 40 years (premature menopause) or 40–45 years (early menopause) and increased risks of cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, chronic lung illnesses, osteoporosis, and premature death [3–7].

Multimorbidity is characterised by the coexistence of 2 or more health conditions [8]. It is a prevalent and complex health concern that presents noteworthy challenges for healthcare systems worldwide [9]. There is increasing interest in researching and tackling multimorbidity among adults [10]. Over half of the worldwide adult population aged 60 years and older encounter multimorbidity [11]. However, there has been limited research exploring the association between menopausal age and multimorbidity in postmenopausal women, although previous studies have examined the association between age at menopause and certain chronic disorders [3–7].

Menopause-induced depletion of ovarian hormones, particularly oestrogen, may impact various organs and systems, potentially resulting in the development of multiple health conditions [12]. Understanding the association between menopausal age and multimorbidity may pave the way for new strategies to develop personalised medicine and targeted interventions. Therefore, the present study employed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to analyse the association between menopausal age and multimorbidity in postmenopausal women in the United States. We hypothesised that young age at menopause would increase the risk of developing multiple chronic conditions in women after menopause.

Material and methods

Data source and study population

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, carried out by the National Center for Health Statistics, gathers health information from a sample of US noninstitutionalised people representing the entire country. Demographic data, nutrition records, examination outcomes, laboratory measurements, and questionnaire answers were included in the NHANES datasets [13]. The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board authorised the NHANES protocol. All NHANES participants gave their written consent. All aspects of the study, including the design, data collection, analysis, and publication writing, were carried out in complete adherence to the standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (https://www.equator-network.org/).

This study included the NHANES survey cycles of 2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2013–2014, and 2017–2018, because other cycles did not cover the information on osteoporosis or age regarding the health conditions of interest. The study population was postmenopausal women aged 40 years and above. Excluded from this study were women who had not yet undergone menopause or whose menopausal age was not specified. Furthermore, those whose age at the onset of hypertension, diabetes, cancer, osteoporosis, thyroid illness, arthritis, coronary heart disease (CHD), heart failure, stroke, heart attack, angina, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and liver disease was equal to or less than their age at menopause were also excluded from the study. Therefore, 3168 postmenopausal women were included in the current analysis.

Exposure variables

Age at menopause was the exposure variable, ascertained by gathering self-reported information on postmenopausal women’s age at the end of their menstrual cycle. Natural menopause was physiological amenorrhoea that persisted for a minimum of 12 months not due to bilateral oophorectomy, pregnancy, or breastfeeding [14]. Surgical menopause was defined as suffering from bilateral oophorectomy before natural menopause [15].

Two cohorts were classified based on the type of menopause. The first cohort comprised 2703 women who experienced natural menopause. The second cohort consisted of 465 women who experienced surgical menopause. Age at menopause was categorised into 4 groups within each cohort: premature menopause (< 40 years), early menopause (40–44 years), reference category (45–54 years), and late menopause (≥ 55 years) [16–18]. Because of the small sample size of ages at surgical menopause ≥ 55 years, ages at surgical menopause 45–54 and ≥ 55 years were combined into one group of ages at surgical menopause ≥ 45 years.

In addition, age at menopause was considered a continuous variable in each cohort. To enable comparisons between the 2 cohorts, we further classified age at any type of menopause into 4 distinct groups: age at natural menopause < 40 years, age at natural menopause ≥ 40 years (reference group), age at surgical menopause < 40 years, and age at surgical menopause ≥ 40 years.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome variable was multimorbidity, which was defined as having 2 or more of the 15 self- reported health conditions: hypertension, diabetes, obesity, cancer, osteoporosis, thyroid illness, arthritis, coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke, heart attack, angina, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and liver disease [19, 20]. Participants were categorised as having the health disorder if they responded affirmatively to the question, Have you ever been diagnosed with (condition) by a doctor or other healthcare professional? Obesity was identified by body mass index equal to or more than 30 kg/m2 [21]. Participants who reported having CHD, heart failure, stroke, heart attack, or angina were classified as having CVD.

Covariates

The covariates included age, race, marital status, education, family monthly poverty level index (FMPLI), smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, age at menarche, parity, use of contraceptive pills, and hormone therapy usage. Age, FMPLI, age at menarche, parity (number of live births), and physical activity were treated as continuous variables.

We assessed physical activity using metabolic equivalent scores (METs), which were calculated by summing the total minutes of intense work-related or leisure-time activity and moderate work-related or leisure-time activity each week. The weight factors assigned to strenuous and moderate activities were 8 and 4, respectively. Subsequently, we computed the mean METs per hour per week as the numerical representation of the physical activity variable [22, 23].

We separated race into 2 categories: non-Hispanic whites and other races. Education was classed as high school or less and college graduate or college. Participants were classed by marital status as those married or living with a partner and others. We classified smoking status into 3 categories: current, past, and never. This classification was based on 2 questions: Have you smoked a minimum of 100 cigarettes throughout your lifetime? and Are you currently a smoker? The alcohol consumption was assessed based on the participant’s responses to the question, Have you consumed a minimum of 12 alcoholic drinks per year?

The data on birth control pills and hormone therapy were collected by asking participants 2 questions: Have you ever used birth control pills? and Have you ever taken hormone therapy? The occurrence of miscarriages/abortions/stillbirths was obtained by subtracting the number of live births from the total number of pregnancies.

To address the variables’ missing values, we utilised multiple imputations. This involved generating imputed values for the missing data using observed information, assuming the missingness occurred at random. The “mice” package in the R software was employed to perform these imputations [24, 25].

Statistical analysis

We followed the NHANES analysis principles regarding data integration and sample weighting. We employed mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency (weighted proportions) for categorical variables to describe participant characteristics. The Rao-Scott χ2 test was applied to compare weighted proportions among different menopausal age groups. ANOVA was used to compare the mean values of continuous variables across different groups.

We also calculated the prevalence of single disease and multimorbidity in postmenopausal women by menopausal age groups. A single disease’s prevalence was derived by dividing the number of women with the disease by the total population. The prevalence of multimorbidity was computed by dividing the number of women with 2 or more health disorders by the total number.

Logistic regression models were employed to compute odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the menopausal age groups of < 40, 40–44, and ≥ 55 years in comparison to 45–54 years. We created 3 models by including potential confounding factors to investigate the association between age at menopause and individual diseases and multiple health conditions. Model 1 controlled age, whereas Model 2 controlled age, race, education, marital status, FMPLI, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. In addition, Model 3 accounted for variables such as age at menarche, parity, history of miscarriage/abortion/stillbirth, usage of birth control pills, hormone therapy, and covariates from Model 2. Also, we employed logistic regression models incorporating restricted cubic splines to estimate OR and 95% CI for the association between age at menopause, treated as a continuous variable, and multimorbidity [26, 27].

To comprehensively investigate the association between age at menopause and multimorbidity, we analysed the interactive effects of age at menopause with potential confounders, including age, race, marital status, education, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, parity, usage of birth control pills, and taking hormone therapy [28–30]. In addition, we performed sensitivity analyses using the complete observation database, which included no missing covariate values, to verify the results’ reliability. We performed the statistical analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R software (version 4.3.0). The statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed p-value below 0.05.

Results

Basic characteristics of study population

The 3168 participants had a mean age of 65.0 ±10.4 years. The distributions of race and education exhibited significant variation in women undergoing natural menopause. Specifically, women who experienced menopause before 40 years of age had a greater probability of being of other races/ethnicities and possessing a high school diploma or less; however, this difference was not statistically significant in the case of women who underwent surgical menopause. The family monthly poverty level index mean showed a significant rise with age at natural menopause, while there were no significant changes in the mean values for women having surgical menopause (Table 1).

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of 3168 postmenopausal women over 40 by menopausal age and types

By physical activity, the menopausal age group of 40–44 exhibited the highest level regardless of natural or surgical menopause. Significant differences in the percentages of women who smoked or took hormone therapy were observed in women with natural menopause but not in women with surgical menopause. The percentages of women with alcohol consumption varied significantly in those undergoing surgical menopause. As the age at menarche increased, so did the age at natural menopause, but not at surgical menopause. Parity exhibited a significant increase with advancing age at menopause. The proportions of using birth control pills or having a history of pregnancy loss differed insignificantly across the menopausal age groups.

Prevalence of health conditions

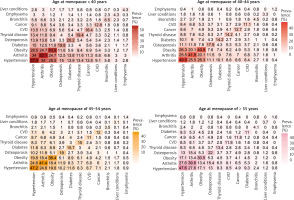

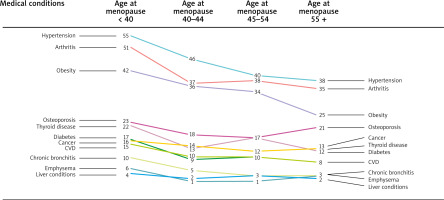

Figure 1 presents the prevalence of each health condition in postmenopausal women. The overall prevalence trend of each single disease declined with increasing age at menopause except for thyroid disease. The prevalence of hypertension was the highest among these health disorders, reaching 54.5%, 45.9%, 39.7%, and 38.2% in women with age at menopause of < 40, 40–44, 45–54, and ≥ 55 years, respectively. Other diseases in descending order of prevalence were arthritis, obesity, osteoporosis, thyroid disease, diabetes, cancer, CVD, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and liver conditions.

Fig. 1

The prevalence (%) of a single medical condition in 3168 postmenopausal women by menopausal age group

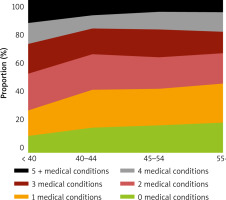

The prevalence of pairs of multimorbidity health conditions decreased with age at menopause, as shown in Figure 2. The most prevalent pairs of disorders were hypertension-arthritis and hypertension-obesity, irrespective of menopausal age groups. Figure 3 illustrates the composition proportion of women having different numbers of health conditions by menopausal age groups. Women experiencing menopause before 40 years of age had the lowest proportion of being free from any health issue (10.9%) and having only one health condition (16.3%). In comparison, they had the highest proportion of having 5 or more health conditions (15.3%). Those undergoing menopause after 55 years of age had the highest proportion of 0 and 1 health conditions (19.9% and 25.2%, respectively) and the lowest proportion of 5+ health conditions (7.7%).

Association between age at menopause and multimorbidity

The adjusted OR (95% CI) for multimorbidity in natural menopausal age groups < 40, 40–44, and ≥ 55 years compared to age at menopause of 45–54 years were 4.71 (3.23–6.86), 1.30 (0.91–1.86), and 0.62 (0.43–0.89), respectively. The adjusted OR for the association between age at surgical menopause of < 40 and 40–44 years and having multiple chronic conditions were 2.67 (1.26–5.66) and 1.65 (0.67–4.05), respectively, compared to age at surgical menopause of ≥ 45 years (Table 2).

Table 2

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the association between age at menopause and multimorbidity among postmenopausal women

[i] Values that are highlighted in bold are significant. Model 1 was age-adjusted. Model 2 accounted for adjustments in age, race, education, marital status, family monthly poverty level index, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. Model 3 adjusted for the influence of age at menarche, history of miscarriages/abortions/stillbirths, parity, usage of birth control pills, hormone therapy, and the covariates included in Model 2.

Table 3 shows significant adjusted associations between age at menopause and each health condition except for liver condition. For example, the adjusted OR (95% CI) for hypertension in women with age at menopause of < 40, 40–44, and ≥ 55 years were 2.43 (1.79–3.30), 1.84 (1.39–2.43), and 0.74 (0.54–1.02) compared to 45–54 years, respectively. For liver disease, the corresponding OR were 1.34 (0.75–2.40), 0.81 (0.37–1.79), and 1.03 (0.37–2.87). Compared to age at natural menopause of ≥ 40, the adjusted OR (95% CI) for age at natural menopause of < 40, age at surgical menopause of < 40 and ≥ 40, were 4.32 (3.11–6.02), 3.94 (2.04–7.61), and 1.89 (1.17–3.05), respectively (Table 4).

Table 3

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the association between age at menopause and each of the 15 medical conditions in 3168 postmenopausal women

[i] Values that are highlighted in bold are significant. Model 1 was age-adjusted. Model 2 accounted for adjustments in age, race, education, marital status, family monthly poverty level index, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. Model 3 adjusted for the influence of age at menarche, history of miscarriages/abortions/stillbirths, parity, usage of birth control pills, hormone therapy, and the covariates included in Model 2.

Table 4

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for the association between natural or surgical menopausal age < 40 or ≥ 40 and multimorbidity in 3168 postmenopausal women

[i] Values that are highlighted in bold are significant. Model 1 was age-adjusted. Model 2 accounted for adjustments in age, race, education, marital status, family monthly poverty level index, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. Model 3 adjusted for the influence of age at menarche, history of miscarriages/abortions/stillbirths, parity, usage of birth control pills, hormone therapy, and the covariates included in Model 2.

In women undergoing menopause before 40 years of age, the adjusted OR for having 2, 3, 4, or 5+ health conditions were 2.97 (2.14–4.12), 3.09 (1.99–4.88), 3.76 (2.09–6.78), and 5.71 (3.17–10.3), respectively, compared to women with age at menopause of 45–54 years (Table 5). In contrast to the same reference group, the adjusted OR for having 5+ health conditions were 1.93 (1.14–3.27) and 0.50 (0.26–0.96) for women aged 40–44 and > 55 years at menopause, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the association between age at menopause and the number of multimorbidity in 3168 postmenopausal women

[i] Values that are highlighted in bold are significant. Model 1 was age-adjusted. Model 2 accounted for adjustments in age, race, education, marital status, family monthly poverty level index, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. Model 3 adjusted for the influence of age at menarche, history of miscarriages/abortions/stillbirths, parity, usage of birth control pills, hormone therapy, and the covariates included in Model 2.

Figure 4 illustrates the adjusted association between menopausal age as a continuous variable and multimorbidity. Significant associations were observed between age at natural or surgical menopause and multimorbidity; the associations were linear, with respective p-values for the nonlinearity of 0.089 and 0.232.

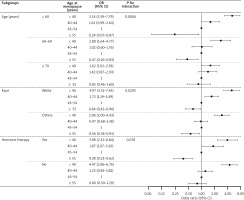

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis

Significant interactions were identified only between age at menopause and age as well as race, not with hormone therapy, according to the statistical threshold of p < 0.05. The association between menopause age and multimorbidity varied significantly among age groups. For example, among women over 60 years old, age at menopause of ≥ 55 years was related to a lower incidence of multimorbidity, but not in women over 70 years of age. Additionally, the association between age at menopause of 40–44 years and multimorbidity was significant in White women but not in other race groups. The interaction effects between age at menopause and hormone therapy on the association between age at menopause and multimorbidity was insignificant (Fig. 5). The sensitivity analysis, conducted on the complete observations before multiple imputations of covariates, did not change the overall conclusions (Suppl. Table 1).

Figure 5

Subgroup analysis of age, race, and hormone therapy for the association between age at menopause and multimor bidity in postmenopausal women over 40

Note: The reference group of age at menopause was 45–49 years. The controlled covariates were race, education, marital status, family monthly poverty level index, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, menarche age, history of miscarriages/abortions/stillbirths, parity, and use of birth control pills.

Discussion

We found that premature menopause was associated with elevated risks of each of the 14 health disorders and multimorbidity, except for liver disease, as compared to age at menopause of 45–54 years in postmenopausal women over 40 years of age. Early menopause was only related to hypertension or CVD and did not exhibit heightened risks of any other individual disease. Nevertheless, continuous menopausal age was inversely and linearly related to multimorbidity, irrespective of menopausal type.

Compared to the normal menopause age, we found that premature and early menopause increased multimorbidity risks by 4.25 and 1.46 times, respectively. Consistently, a prospective Australian study of 5017 par- ticipants reported that women undergoing premature menopause had twice the possibility of developing multimorbidity by age 60 years (OR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.31–2.98) and 3 times the likelihood of having multimorbidity in their 60s (OR = 3.03, 95% CI: 1.62–5.64), in comparison to women with menopausal age of 50–51 years [1].

Multiple studies demonstrated that women experiencing premature menopause had higher risks of developing chronic illnesses, including hypertension, metabolic disorders, diabetes, CVD, cancer, and osteoporosis [3, 31–35]. A meta-analysis of 10 studies showed that women with age at menopause of < 45 years had a higher risk of developing hypertension than those with age at menopause of ≥ 45 years (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.01–1.19) [31]. Another pooled ana- lysis of 3 prospective studies reported adjusted hazard ratios for CHD, stroke, and heart failure in nondiabetic women with menopausal age of < 45 of 1.09 (1.03, 1.15), 1.10 (1.04, 1.16), and 1.09 (1.03, 1.16), respectively, compared to menopausal age of ≥ 45 years [32]. However, some studies reported that late age at menopause could elevate risks of breast cancer and endometrial cancer, showing a positive dose-response relationship [36, 37].

We observed consistently significant associations between premature menopause and either a single health condition (except for liver disease) or multimorbidity. However, early menopause was only statistically associated with hypertension or CVD and did not show a statistically significant association with any other single disease (Table 3). This finding aligned with some studies [3, 38]. For example, a study of 1892 postmenopausal women from NHANES III (1988–1994) reported that the OR for arthritis in women with age at menopause of < 40 and 40–49 years were 2.53 (1.41–4.53) and 1.11 (0.69–1.77), respectively, compared to age at menopause ≥ 50 years [38]. However, the recent Pittsburgh Lung Screening Study involving 1666 female smokers found that age at menopause < 45 years was associated with increased risks of chronic bronchitis and emphysema, with the OR (95% CI) of 1.73 (1.19, 2.53) and 1.70 (1.25, 2.31), respectively, compared to age at menopause of ≥ 45 years [39]. The discrepancy may be ascribed to the different classifications of age at menopause and the reference group (our study: age at menopause of 40–44 vs. 45–54; the cited study: age at menopause < 45 vs. ≥ 45). Additionally, the difference in research populations (our study: general postmenopausal women; the cited study: female postmenopausal smokers) may have contributed to the variation.

We found no association between menopausal age and liver disease. Similarly, a study of 4354 postmenopausal women from the Korea NHANES (2010–2012) found no significant differences in the OR of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in women with age at menopause of 45 and 55 years compared to menopausal age of 45–54 years, with an OR (95% CI) of 1.05 (0.83–1.32) and 1.02 (0.75–1.39), respectively [40]. However, some research found that menopausal status was related to increased risks of NAFLD [41, 42]. A cross-sectional study of 1559 women aged 44–56 years, for example, found that post-menopause raised the risks of NAFLD by 67% when compared to pre-menopause [41].

Our results indicate that women with premature menopause had significantly higher odds of developing 2, 3, 4, and 5+ health issues, with the respective OR being 2.97, 3.09, 3.76, and 5.71, respectively, compared to women with age at menopause of 45–54 years. This suggests that the greater the number of diseases, the greater the risk of premature menopause producing multimorbidity, leading to a substantial load of multiple health conditions for women in later life.

Contradictory evidence exists regarding the health effects of hormone therapy on postmenopausal women [43–45]. Some studies have provided evidence linking hormone therapy to the alleviation of menopausal symptoms, as well as reduced risks of osteoporosis and fractures [46, 47]. In contrast, some research demonstrated the potential hazards of hormone therapy on women’s well-being [43, 48, 49]. The Women’s Health Initiative trial reported the following hazard ratios (95% CI) for composite outcomes in the hormone therapy treatment group relative to the control group: 1.22 (1.09–1.36) for CVD, 1.03 (0.90–1.17) for cancer, and 0.76 (0.69–0.85) for combined fractures. That study concluded that the risks of hormone therapy to postmenopausal women’s overall health outweighed the benefits [43]. Similarly, we did not observe any significant interactions between age at menopause and hormone therapy, and we did not find any proof to suggest that hormone therapy affects the association between age at menopause and multimorbidity (Fig. 5).

The intricate biological mechanisms that explain the association between the age at which menopause occurs and the presence of several chronic diseases are still not wholly comprehended [50, 51]. Several explanations are suggested to elucidate this association. To begin with, premature or early menopause results in a significant decline in oestrogen levels occurring at a younger age than typical menopause [4, 52]. Oestrogen plays a vital role in controlling various physiological functions, including blood vessel dilatation, maintaining endothelial function, modifying the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, metabolic regulation, and promoting bone health [53–55]. The sudden reduction in oestrogen can alter these regulatory processes, potentially contributing to elevated blood pressure, metabolic problems, CVD, osteoporosis, and other related conditions [31, 56, 57].

In addition, premature or early menopause has been related to expedited aging mechanisms at the cellular and molecular levels [58, 59]. The acceleration of aging processes, such as cellular senescence and DNA damage, might heighten vulnerability to some age-related chronic conditions [60, 61]. Besides, women going through premature or early menopause may have similar negative lifestyle characteristics, such as smoking, unhealthy food, or other habits connected to health. These factors may not only contribute to an early onset of menopause but also elevate the likelihood of having various chronic illnesses simultaneously [62, 63].

Regarding the study’s strengths, our study provides representative results of American postmenopausal women. In the study design, we excluded participants who were diagnosed with any of the health conditions before reaching menopause. This could address the deficiencies of cross-sectional data in establishing causal relationships to a certain degree. In addition, we performed comprehensive studies to analyse the associations, utilising age at menopause as both categorical and continuous variables. For the outcome variable, we conducted analyses on each specific health condition, the presence of multiple health conditions, and the varying number of these multiple health conditions. Furthermore, we investigated potential interaction effects and carried out sensitivity analysis.

The study had several limitations. Firstly, the participants’ self-reports of menopause information render them vulnerable to recall bias. Secondly, due to the exclusion of osteoporosis in some survey cycles, our analysis was limited to 4 NHANES survey cycles. This resulted in an inadequate sample size to analyse the age at surgical menopause of ≥ 55 years. Additionally, the lack of information regarding the duration of hormone therapy in the NHANES datasets prevented us from analysing the effects of hormone therapy duration on the association between age at menopause and multimorbidity in postmenopausal women.

Menopause is a universal biological phenomenon, and its timing affects women’s health globally. Multimorbidity is an escalating worldwide health concern, especially with the rise in life expectancy. Examining the association between menopausal age and multimorbidity can offer insights to guide preventative health initiatives for women in various cultural and healthcare settings. It may help establish a basis for global partnerships to further explore the nexus of menopause, aging, and chronic disease management. This study’s findings can inform public health activities focused on identifying women at risk for multimorbidity according to their menopausal age.

Conclusions

This study used a representative sample of the US population to examine the association between age at menopause and multimorbidity. Premature menopause was associated with hypertension, diabetes, CVD, cancer, arthritis, obesity, osteoporosis, thyroid disease, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema, as well as the coexistence of multiple health disorders. Early menopause was associated with hypertension and CVD. We observed linear and inverse associations between continuous menopausal age and multimorbidity. Additionally, the impact of hormone therapy on the association between age at menopause and multimorbidity was found to be insignificant. The implications of our findings highlighted the importance and necessity of implementing early monitoring and intervention techniques to alleviate the burden of multimorbidity in women experiencing premature or early menopause. For future research directions, we suggest focusing on longitudinal studies to establish causal relationships between age at menopause and multimorbidity, investigating the biological pathways linking age at menopause to multimorbidity, exploring interventions designed to mitigate the effects of premature menopause on multimorbidity, and utilising precision medicine to identify subgroups of women most at risk for multimorbidity based on their menopausal timing and genetic, epigenetic, or environmental factors.