Introduction

Urinary incontinence affects half of the adult female population worldwide [1], significantly impairing their quality of life [2]. It leads to social isolation, lower self-esteem, depression and reduced quality of sexual life [2]. Women with incontinence avoid intercourse and also show less sexual desire and lower sexual satisfaction than women without incontinence. Urinary incontinence also leads to a reduction in women’s physical activity [3].

According to the International Continence Society (ICS) definition, urinary incontinence is ‘any involuntary leakage of urine’, meaning that it can range from minor, sporadic episodes to severe, chronic cases of complete loss of bladder control [4].

Urinary incontinence is divided into stress urinary incontinence, which is associated with activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure (e.g. playing sports, sneezing, coughing, laughing), and urge urinary incontinence, in which urine leaks due to a sudden, strong urge to urinate. Women with both types of incontinence are diagnosed with mixed incontinence [5].

A study by Akbar et al. compared the prevalence of different types of incontinence in different ethnic groups. The results showed that stress urinary incontinence is more common among women living in China and South American countries, while urge incontinence is predominant among African-American women, and mixed incontinence is most common among white women [6].

Factors that increase the likelihood of stress urinary incontinence include age-related changes, multiple vaginal deliveries, obesity, chronic cough and constipation [7, 8]. Anatomical factors that can cause stress urinary incontinence regardless of race should also be mentioned. These primarily include dysfunction of the urethral sphincter muscle, shortening of the functional length of the urethra, lowering of the anterior vaginal wall and weakness or dysfunction of the anal lever muscle [9]. All these factors point to the need for early identification of patients who may be at risk, and for the introduction of effective preventive and therapeutic measures to reduce the incidence of stress urinary incontinence.

Current treatments for stress urinary incontinence include pharmacotherapy, physical therapy (electrostimulation, magnetotherapy and biofeedback) [10] and surgery [11].

A non-invasive and effective treatment for stress urinary incontinence is pelvic floor muscle training to improve muscle coordination [10, 12]. This results in better compression of the urethra during increased intra-abdominal pressure during exercise. By training the pelvic floor muscles (PFM) appropriately, their normal resting tension and contractility can be achieved [13].

Regular training of the PFM helps to improve urinary continence control and is significant in the prevention of postpartum incontinence [14]. Appropriate pelvic floor muscle training is effective in all incontinence subtypes [12, 15] and is a safe method for strengthening pelvic floor muscles, which has been shown to reduce incontinence in both pre- and postmenopausal women [16]. Considering the relevance of the problem of urinary incontinence in women, it was proposed that the original exercise programme be performed for a period of 6 weeks by pre- and postmenopausal women.

The following research hypotheses were identified prior to the study:

H1. The exercise programme will result in less urine loss in the groups of premenopausal and postmenopausal women;

H2. The number of deliveries and route of delivery influence the incidence of urinary incontinence in the before-menopause group exercise (BMGE, premenopausal) and post-menopause group exercise (PMGE, postmenopausal) groups of women;

H3. Pelvic type and postural pattern influence incontinence in both groups of women.

Material and methods

Participants

Women with stress urinary incontinence participated in the study: premenopausal women (n = 30) aged 39.5 ±6.36, whose BMI was 22.70 ±3.38 and who were economically active, and postmenopausal women (n = 42) aged 68.50 ±13.43, whose BMI was 29.51 ±6.86 and who were retired.

All study participants had a medical diagnosis of stress urinary incontinence. Inclusion criterion: the presence of symptoms of stress urinary incontinence confirmed by medical diagnosis, informed written consent to participate in the study, natural delivery or caesarean section. Exclusion criterion: types of incontinence other than stress incontinence (with urgency or mixed incontinence) and women after instrumental delivery (vacuum or forceps). An interview was conducted with all subjects, in which the women interviewed reported the number of deliveries. All women gave informed and written consent to participate in the study.

Urinary incontinence assessment test

To assess the degree of incontinence, a modified 1-hour pad test was used, which is one of the least invasive tools to measure urinary loss [17, 18]. The test was conducted before and after the start of the exercise programme. Prior to the test, study participants were explained how to perform the test, and the test was conducted in accordance with ICS guidelines [19]. The study participant wore a pad previously weighed on a BLOW JS12 electronic jewellery scale and drank 500 ml of water over 15 minutes. The subject then waited 30 minutes. After this time, the test began with 15 minutes of walking and stair climbing. The subject then performed a special training programme (designed to induce urine loss): 10 times she stood up and sat down on a chair, 10 times she coughed vigorously, 10 times she lifted a water bottle from the ground, ran in place for 1 minute and held her hands under running cold water for 1 minute. After the test, the pad was weighed again (the result was read electronically) and the amount of urine lost during the test was assessed. A weight of the pad greater by at least 2 grams after the test indicates urinary incontinence.

The degrees of incontinence based on the 1-hour incontinence pad test are defined as follows: < 2 g: no incontinence, 2–10 g: medium degree, 10–50 g: severe degree of incontinence, 50 g: very severe degree of incontinence. The incontinence test was assessed by one researcher.

Hall-Wernham-Littlejohn postural pattern type assessment

A plumb line was used to assess postural type. The female subject was positioned sideways against a wall in her underwear, then the examiner applied the plumb line to the external auditory canal. With a correct silhouette, the plumb line should run symmetrically in a line through the shoulder joint, the hip plateau and through the lateral talus of the knee joint [20]. The assessment of the postural pattern was based on the silhouette presented by the female subject [21]. Type I – anterior: head and shoulder protraction and deepened lumbar lordosis were observed; type II – normal; type III – posterior: head and shoulder retraction and flattened lumbar lordosis were observed [21]. The postural pattern was determined prior to the start of the exercise programme. The type of postural pattern was assessed by one examiner, who also performed the bolster test.

Pelvic type assessment

When assessing pelvic type, the female subject was in her underwear, standing with her back to the assessor. The pelvic type assessment was based on the manual examination according to Levit and referred to the level of the hip plates relative to the lumbar spine. In the female subject, the level of the L4–L5 lumbar vertebrae was determined, and then the assessor checked the level of the hip plates. If the level of the plates was above the L4–L5 vertebrae, the pelvis was defined as type I, i.e. high-assisted; if the level of the hip plates fell at the L4–L5 level, the pelvis was defined as type II intermediate; and if the level of the hip plates fell below the level of the L4–L5 vertebrae, the pelvis was defined as type III overloaded [22]. Pelvic type was determined before the start of the exercise programme. The pelvic type was assessed by a single investigator who also performed the bolster test and assessed the type of postural pattern.

Original exercise programme

Participants in the study followed an original exercise programme for six weeks. The exercises were performed three times a week at a fixed time of day, including once a week under the supervision of an instructor, while on the other days of the week the participants performed the exercises independently at home (before performing the exercises independently, each woman was instructed by the instructor on how to perform the exercises correctly). The exercise programme was comprehensive and included exercises to feel and imagine the work of the pelvic floor muscles, breathing exercises focusing on the diaphragmatic breathing path using the side-ankle technique, and exercises to strengthen the PFM together with movement of the upper limbs, trunk and lower limbs. The aim of the exercises was to strengthen the PFM which, according to the literature, requires a minimum of six weeks to notice effects [23]. The exercise programme was conducted by a single researcher carrying out a postural support test, as well as assessing postural pattern type and pelvic type. The following utensils were used in the exercises: a gym ball with a diameter of 22 cm, dumbbells with a weight of 2 kg, red resistance band, balloon.

Exercise methodology by week

WEEK 1

The aim was to learn the correct activation of PFM and correct breathing.

Exercise 1. Starting position (SP): sit on a chair, lower limbs bent at the knee and hip joints to 90 degrees, feet resting on the ground, positioned hip-width apart, spine in the intermediate position, hands resting on the side of the lower ribs. Movement (M): breathing with the lower rib cage area. 1 series. Number of repetitions (NR): 20× in a series.

Exercise 2. SP: lying supine, knees bent, feet resting on the ground. Prior to the exercise, the subject was shown a pelvic model to understand the anatomical structure of the PFM. M: visualisation of a clock face lying on the pelvis. Tensing the PFM in the direction corresponding to the time on the clock. 2 series. NR: 12× in each series.

Exercise 3. SP: kneeling sit [24]. M: PFM tensions. 3 series. NR: 20× in each series.

Exercise 4. SP: sit on a chair, lower limbs bent at the knee and hip joints to 90 degrees, feet resting on the ground set at hip width, spine in the intermediate position. M: Tense the PFM by ‘bringing’ the ischial tuberosities together as you exhale. Then long inhalation and relaxation of the PFM. 1 series. NR: 20× in a series.

Exercise 5. SP: as above (aa). M: Tense the PFM by ‘bringing’ the sacrum and pubic symphysis together as you exhale. Then long inhalation and relaxation of the PFM. 1 series. NR: 20× in a series.

Exercise 6. SP: aa. M: Tense the PFM during exhalation. Then long inhalation and relaxation of SWF. 3 series. NR: 20× in each series.

Exercise 7. SP: aa. M: movement of the pelvis in the posterior tilt direction with simultaneous tensing of the PFM during exhalation. Then, on inhalation, movement of pelvis towards front tilt and relaxation of PFM. 3 series. NR: 10× in each series.

WEEK 2

Exercise 1. SP: aa, hands resting from the side on the lower ribs. M: breathing with the lower rib cage area. 1 series. NR: 20× in a series.

Exercise 2. SP: lie back, knees bent, feet resting on the ground. M: Tense the transversus abdominis muscle as you exhale by ‘pulling’ the navel downwards. Then inhale and relax the transversus abdominis muscle. 3 series. NR: 20× in each series.

Exercise 3. SP: aa. M: rapid tensing and relaxing of the PFM, at a pace counted down by the investigator. Command 1 indicated muscle tension, while 2 meant muscle relaxation. 3 series. NR: 20× in each series.

Exercise 4. SP: aa, gymnastics ball between knees. M: lift hips up while exhaling with simultaneous tension of PFM. Then return to SP while inhaling and relax PFM. 4 series. NR: 8× in each series.

Exercise 5. SP: supported kneeling [24], lower limbs at hip joints in abduction, feet facing outwards, spine in the intermediate position. M: transition to supported kneeling while exhaling with simultaneous PFM tensing. Then returning to SP while inhaling and relaxing the PFM. 4 series. NR: 12× in each series.

Exercise 6. SP: supported kneeling [24] on forearms set in pronation, shoulder blades pulled back, spine in the intermediate position. M: 10-second isometric contraction of the PFM with simultaneous knee lift. Then relaxation of the PFM, lowering of the knees to the ground and rest, during which the subject breathed using the lateral rib technique. 4 series. NR: 10 seconds of PFM tensing followed by 10 breaths while resting in each series.

Exercise 7. SP: one-legged kneel [24], right lower limb in front, upper limbs forward, gymnastics ball squeezed between hands, shoulder blades pulled together. M: rotation of the trunk towards the right lower limb during exhalation with simultaneous PFM tensing. Then return to SP during inhalation and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 6× on the right side, 6× on the left side in each series.

Exercise 8. SP: lie back, knees bent, feet on the ground, shoulder blades pulled together, hands at sternum level, squeeze grip hold ball. M: lift the upper limbs with the ball upwards during exhalation with simultaneous tensing of the PFM. Then return to SP while inhaling and relax PFM. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 9. SP: one-legged side sit [24], left foot behind hip line so that the angle between the thigh and shin in both lower limbs is 90 degrees. M: change SP from left to right so that the right foot is behind the hip line. 3 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 10. SP: supported kneeling [24] with forearms set in pronation, shoulder blades pulled back, spine in the intermediate position. M: breathing with the side-ankle technique. 1 series. NR: 10× in a series.

WEEK 3

Exercise 1. SP: sit on a chair, lower limbs bent at the knee and hip joints to 90 degrees, feet resting on the ground, positioned hip-width apart, spine in the intermediate position, hands resting on the side of the lower ribs. M: breathing with the lower rib cage area. 1 series. NR: 20× in a series.

Exercise 2. SP: lying backwards, knees bent, feet resting on the ground. M: rapid tensing and relaxing of the PFM, at a pace counted down by the examiner. Command 1 indicated muscle tension, while 2 meant muscle relaxation. 3 series. NR: 20× in each series.

Exercise 3. SP: supported kneeling [24], spine in the intermediate position. M: curve the spine convexly in all sections during exhalation with simultaneous PFM tensing. Then return spinal alignment to the intermediate position during inhalation and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 4. SP: lying supine, lower limbs flexed, hip joints set in external rotation, feet joined, heels close to buttocks. M: 5-second isometric contraction of the PFM. Followed by relaxation of the PFM and rest, during which the subject breathed using the side-ankle technique. 4 series. NR: 5 seconds of PFM tensing followed by 5 breaths while resting in each series.

Exercise 5. SP: lying forward, upper limbs up. M: raise upper and lower limbs while exhaling with simultaneous PFM tensing. Then return to SP while inhaling and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 6. SP: bipedal stride [24], palms against the wall, forearms in pronation, upper limbs straight at the elbow joints, spine in the intermediate position, shoulder blades pulled together. M: Approach the wall by bending the upper limbs at the elbow joints while inhaling. Then pushing away from the wall with simultaneous tension of the PFM. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 7. SP: supported kneeling [24] on forearms set in pronation, shoulder blades pulled back, spine in the intermediate position. M: 15-second isometric contraction of the PFM with simultaneous lifting of the knees. Then relaxation of the PFM, lowering the knees to the ground and resting, during which the subject breathed using the lateral rib technique. 4 series. NR: 15 seconds of PFM tensing followed by 10 breaths while resting in each series.

Exercise 8. SP: bipedal stride [24], upper limbs forward, palms grip squeezing ball, shoulder blades pulled together. M: squat below 90 degrees of knee joint flexion while inhaling, simultaneously squeezing the ball with hands. Then return to SP while exhaling with simultaneous PFM tensing. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 9. SP: supported kneeling [24], spine in the intermediate position, shoulder blades pulled together. M: right lower limb extension and left upper limb flexion during exhalation with simultaneous PFM tensing. Then return to SP during inhalation and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 6× for right side, 6× for left side in each series.

Exercise 10. SP: lying backwards, knee joints bent to 90 degrees, feet resting against wall. M: raise hips and hold position while breathing using the side-ankle technique. 1 series. NR: 15× in a series.

WEEK 4

Exercise 1. SP: sit on a chair, lower limbs bent at the knee and hip joints to 90 degrees, feet resting on the ground, positioned hip-width apart, spine in the intermediate position, hands resting laterally on the lower ribs. M: breathing with the lower rib cage area. 1 series. NR: 20× in a series.

Exercise 2. SP: lie back, lower limbs bent at hip and knee joints to 90 degrees, upper limbs forward, gymnastics ball in hands. M: straighten lower limbs and bend upper limbs while inhaling, hands squeeze ball during movement. Then return to SP while exhaling with simultaneous PFM tensing. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 3. SP: standing in a supine position [24], the right lower limb is the supine limb, the upper limbs are forward, the hands hold a stretched resistance rubber band fixed on the left side (when changing limbs in the supine position, the rubber band is fixed on the right side). M: twist the trunk towards the right lower limb during exhalation with simultaneous PFM tensing. Then return to SP during inhalation and relax PFM. 4 series. NR: 6× on the right side, 6× on the left side in each series.

Exercise 4. SP: supported kneeling [24] on forearms set in pronation, shoulder blades pulled back, spine in the intermediate position. M: 20-second isometric contraction of the PFM with simultaneous knee lift. Then relaxation of the PFM, lowering the knees to the ground and resting, during which the subject breathed using the lateral rib technique. 4 series. NR: 20 seconds of PFM tensing followed by 10 breaths while resting in each series.

Exercise 5. SP: bipedal stride [24], upper limbs forward, hands grip a gymnastics ball, shoulder blades pulled together. M: squat below 90 degrees of knee joint flexion while inhaling, holding the ball with a squeezing grip. Then return to SP while exhaling with simultaneous PFM tensing. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 6. SP: lie back, knees bent, gymnastics ball between the knees, feet resting on the ground, hips raised. M: straighten the right lower limb at the knee joint while exhaling with simultaneous PFM tensing. Then return to SP while inhaling and relax the PFM. 3 series. NR: 6× for right side, 6× for left side in each series.

Exercise 7. SP: one-legged side sit [24], left foot behind hip line so that the angle between the thigh and shin in both legs is 90 degrees. M: change SP from left to right so that the right foot is behind the hip line. 3 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 8. SP: lying backwards, knee joints bent to 90 degrees, feet resting against the wall. M: raise hips and hold the position while breathing with the lateral rib technique. 1 series. NR: 15× in a series.

WEEK 5

Exercise 1. SP: sit on a chair, lower limbs bent at the knee and hip joints to 90 degrees, feet resting on the ground, positioned hip-width apart, spine in the intermediate position, hands on the side of the lower ribs. M: breathing with the lower rib cage area. 1 series. NR: 20× in a series.

Exercise 2. SP: bipedal stride [24], spine in the intermediate position, shoulder blades pulled back, upper limbs along the torso, dumbbells in hands. M: bend at the knee joints and flex at the hip joints on inhalation while lowering the dumbbells. Then return to SP on exhalation with simultaneous PFM tension. 4 series. NR: 8× in each series.

Exercise 3. SP: lying backwards, knees bent, feet resting on the ground. M: rapid tensing and relaxing of the PFM, at a pace counted down by the examiner. Command 1 indicated muscle tension, while 2 meant muscle relaxation. 3 series. NR: 20× in each series.

Exercise 4. SP: supported kneeling [24] on forearms set in pronation, shoulder blades pulled back, spine in intermediate position. M: 25-second isometric contraction of the PFM. This was followed by relaxation of the PFM, lowering the knees to the ground and resting, during which the subject breathed using the lateral-ankle technique. 4 series. NR: 25 seconds of PFM tension followed by 10 breaths while resting in each series.

Exercise 5. SP: lying supine, right lower limb with knee straightened, left lower limb with knee bent to 45 degrees and foot resting on the ground, knees squeezed a gymnastics ball. M: hip elevation on exhalation with simultaneous PFM tension. Then return to SP while inhaling and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 6× for right side, 6× for left side in each series.

Exercise 6. SP: lie on your front, palms on the floor at shoulder height. M: straighten upper limbs with trunk lift on exhalation with simultaneous PFM tension. Then return to SP while inhaling and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 7. SP: lying sideways [24], support on the right forearm set in pronation, left upper limb along the torso, shoulder blades pulled together, lower limbs at the knee joints bent to 90 degrees. M: hip elevation during exhalation with simultaneous PFM tension. Then return to SP during inhalation and relax PFM. 4 series. NR: 10× for right side, 10× for left side in each series.

Exercise 8. SP: bipedal stride [24], upper limbs forward, shoulder blades pulled together, hands squeeze gymnastics ball. M: side bend of the trunk to the right while inhaling. Then return to SP while exhaling with simultaneous PFM tension. 4 series. NR: 8× on the right side, 8× on the left side in each series.

Exercise 9. SP: lie back, lower limbs bent at hip joints (set in external rotation) and knee joints, feet joined, heels close to buttocks. M: breathing with the side-ankle technique. 1 series. NR: 15× in a series.

WEEK 6

Exercise 1. SP: lying backwards, knees bent, feet resting on the ground. Balloon in mouth held by hands. M: breathing with the lower rib cage area, where the exhalation was directed to the balloon, pumping it with simultaneous PFM tension. 1 series. NR: 10× in a series.

Exercise 2. SP: bipedal stride [24], hands at shoulder height holding a taut resistance rubber band fixated under the feet. M: squat below 90 degrees of knee joint flexion while inhaling. Then return to SP on exhalation with simultaneous PFM tension. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 3. SP: supported kneeling with feet facing outwards [24], spine in intermediate position. M: transition to supported kneeling [24] while exhaling with simultaneous PFM tension. Then return to SP while inhaling and relaxing the PFM. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 4. SP: supported kneeling [24], spine in the intermediate position, shoulder blades pulled together, a dumbbell was attached to the right lower limb using a resistance band. M: right lower limb extension and left upper limb flexion during expiration with simultaneous PFM tensing. Then return to SP during inhalation and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 6× for right side, 6× for left side in each series.

Exercise 5. SP: one-legged kneel [24], right lower limb in front, balloon in mouth held with hands, shoulder blades pulled together. M: twist the torso towards the right lower limb during exhalation with simultaneous PFM tension and balloon blowing. Then return to SP during inhalation and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 6× for right side, 6× for left side in each series.

Exercise 6. SP: supported kneeling [24], spine in intermediate position. M: curve the spine convexly in all sections during exhalation with simultaneous tension of the PFM. Then return to SP and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 7. SP: lying sideways [24], support on right forearm set in pronation, left upper limb abducted to 90 degrees, shoulder blades pulled back, lower limbs at knee joints bent to 90 degrees. M: Inversion of the lower limb at the hip joint during exhalation with simultaneous PFM tension. Then return to SP while inhaling and relax the PFM. 4 series. NR: 10× for right side, 10× for left side in each series.

Exercise 8. SP: supported kneeling [24], shoulder blades pulled back M: bend upper limbs at elbow joints during inhalation. Then return to SP on exhalation with simultaneous PFM tension. 4 series. NR: 10× in each series.

Exercise 9. SP: supported prone [24]. M: breathing with the side-ankle technique. 1 series. NR: 15× in a series.

Statistical analysis

The R statistical package [25] was used for statistical analysis. Before statistical analysis, the presence of a normal distribution of the data was checked. As its presence was not noted, non-parametric tests were applied.

H1

In order to verify research hypothesis one, the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was used to test whether the exercise programme had an effect on reducing urinary incontinence in the study groups of premenopausal (BMGE) and postmenopausal (PMGE) women. A Dunn’s multiple range test was then used to compare pairs in the groups of premenopausal women (BMGE) before BMGE1 exercise and after BMGE2 exercise and in the group of postmenopausal women (PMGE) before PMGE1 exercise and after PMGE2 exercise. The next step in the statistical analysis was to use the Wilcoxon test to compare incontinence after completion of the exercise programme in the study groups of premenopausal (BMGE) and postmenopausal (PMGE) women.

H2

In order to test the second research hypothesis, i.e. that the number of deliveries and the route of delivery affect the incidence of urinary incontinence in BMGE (premenopausal) and PMGE (postmenopausal) women, the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was applied.

H3

Verification of research hypothesis three that pelvic type and postural pattern influence the incidence of urinary incontinence in BMGE (premenopausal) and PMGE (postmenopausal) women was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test. The results obtained are presented in the form of tables and figures.

Results

H1: The exercise programme led to less urine loss in the pre-menopausal and postmenopausal groups of women.

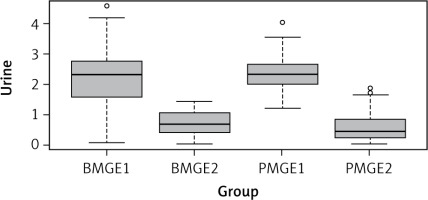

The results indicate that the exercise programme reduced urine loss in both study groups (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Amount of urine lost in premenopausal and postmeno pausal women

BMGE – before-menopause group exercise, BMGE1 – before exercise, BMGE2 – after exercise, PMGE – post-menopause group exercise, PMGE1 – before exercise, PMGE2 – after exercise

Table 1

Kruskal-Wallis test for the exercise programme in the groups of and postmenopausal women

| Parameter | n | Statistic | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | 144 | 93.6 | 3 | < 0.0001 |

The analysis was then performed using the Dunn multiple test. The results showed that a statistically significant result of p = 0.0001 was obtained for the following groups: BMGE1 and BMGE2; BMGE1 and PMGE2; BMGE2 and PMGE1; PMGE1 and PMGE2 (Table 2). These results indicate that performing the author’s exercise programme reduced the amount of urine lost.

Table 2

Multiple Dunn’s test for the amount of lost urine in the study groups of women before and after the author’s exercise programme

The next step in the statistical analysis was to apply the Wilcoxon test. The resulting p = 0.244 indicates that urine loss in the study groups of women was not statistically significantly different, meaning that in both groups of premenopausal (BMGE) and postmenopausal (PMGE) women, the amount of urine lost after exercise was similar.

H2: Number of deliveries and route of delivery affect the incidence of urinary incontinence in BMGE (premenopausal) and PMGE (postmenopausal) women.

Number of births

For premenopausal women (BMGE), a p = 0.7021 was obtained (Table 3). This indicates statistical insignificance, i.e. the number of births in this group does not significantly affect the incidence of urinary incontinence. On the other hand, for the group of women with PMGE (postmenopausal), a p = 0.4073 was obtained (Table 3); i.e. in this group the number of deliveries does not significantly affect the incidence of urinary incontinence.

Type of birth

For premenopausal women (BMGE), a p = 0.713 was obtained (Table 3). It should therefore be inferred that the route of delivery in this group does not significantly affect the incidence of urinary incontinence. In contrast, for the postmenopausal group (PMGE), a p = 0.3613 was obtained (Table 3); i.e. also in this group, the route of delivery does not significantly affect the incidence of urinary incontinence.

H3: Pelvic type and postural pattern affect incontinence in both groups of women.

Pelvic type

For premenopausal women (BMGE), a p = 0.5079 was obtained (Table 3). It should be concluded that the pelvic type of the premenopausal women (BMGE) group does not significantly affect the incidence of urinary incontinence. On the other hand, for the postmenopausal group of women (PMGE), a p = 0.4885 was obtained (Table 3), i.e. also in this group the pelvic type does not significantly affect the incidence of urinary incontinence.

Posture pattern

For premenopausal women (BMGE), a p = 0.7331 was obtained (Table 3), while for postmenopausal women (PMGE) a p = 0.7331 was obtained (Table 3). Thus, it should be concluded that in the groups of premenopausal and postmenopausal women, postural pattern has no significant effect on the incidence of urinary incontinence.

Discussion

The proposed exercise programme performed for six weeks reduced the amount of urine lost in pre- and postmenopausal women. In a study by Alves et al. using pelvic floor muscle exercise training, a positive effect on symptoms of stress urinary incontinence was observed. The study involved 30 postmenopausal women (18 women in the training intervention group and 12 women in the control group) [26]. The authors did not provide an exact exercise methodology taking into account the SP of the exercises and their number of repetitions, but each training session lasted 30 minutes twice a week under the supervision of an instructor, and the exercises were performed for six weeks. The women in our study also exercised for six weeks. The results of the study by Alves et al. [26] indicate that pelvic floor muscle strengthening exercises are effective in postmenopausal women with stress urinary incontinence. A limitation of this study may be the small number of women subjected to the intervention, but, unlike our study, the Alves et al. study included a control group of postmenopausal women, which may influence the greater clinical value of the study. Palpation, sEMG, pelvic organ prolapse assessment (POP-Q) and questionnaires validated by the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaires were used to assess the progress of pelvic floor muscle training in this study [26]. The study by Tosun et al. [27], in which the number of women studied was larger (n = 30 women with stress and mixed urinary incontinence) than in the study by Alves et al. or ours, also confirms the positive effect of pelvic floor muscle training on reducing urinary incontinence. In this study, all participants were divided into a training intervention group (n = 65) and a control group (n = 65). The mean age of the training group was 51.7, while that of the control group was 52.5. The training group performed pelvic floor muscle exercises three times a week under the supervision of a physiotherapist for 12 weeks. The exact exercise methodology in this study was also not provided by the study authors [26, 27]. Assessment of progress was measured by a 1-hour incontinence test, a micturition diary, the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire-7, and the Urogenital Distress Inventory-6. In our study, we also used the incontinence test. In the study by Tosun et al. in the group with the training intervention, a significant improvement was observed in the reduction of incontinence symptoms and an increase in pelvic floor muscle strength compared with the control group. The results indicate that pelvic floor training has a positive effect on symptoms associated with stress and mixed urinary incontinence [27]. Moreover, in a study by Ptak et al. [28], the results confirm that pelvic floor muscle strengthening exercises are effective in women with stress incontinence both before and after menopause and improve women’s quality of life [28]. This study involved women with stress urinary incontinence aged 45–60 years, who were divided into two groups: in the first group, pelvic floor muscle training together with transversus abdominis muscle activation (PFM + TrA) was used, while in the second group only PFM was used. In the first group (PFM + TrA), 47.1% of the women were premenopausal and 52.9% were postmenopausal. In the second group (PFM), 61.4% of the women were premenopausal, while 38.6% of the women were postmenopausal. Both groups performed the following training programme four times a week: three series of 10 repetitions of pelvic floor muscle contractions (60–70% of maximum contraction) and two series of 10 repetitions of pelvic floor muscle contractions (30–60% of maximum contraction). The programme was performed for 12 weeks in both groups, with the only difference included in the exercises being that the women in group two (PFM) were instructed not to tense the transversus abdominis muscle when activating the PFM [28]. The incontinence patients’ quality of life questionnaire was used to assess the progress of exercise [28]. Although greater improvements in various areas of quality of life (performance of household chores and activities outside the home, physical activity, frequency of changing sanitary pads, changing wet underwear, odour anxiety) were obtained by women in group one, significant improvements in quality of life were recorded in both groups, which may indicate that pelvic floor muscle training improves quality of life and reduces incontinence-related symptoms regardless of the age of the patient [28].

The proposed exercise programme is comprehensive and is not limited to isolated pelvic floor muscle contraction, as it also includes global exercises such as squats and exercises involving the abdominal muscles, which, according to the literature, have a better effect on reducing urinary incontinence [29, 30]. The effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training has been repeatedly confirmed and is the gold standard for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence [23]. However, there is still a need for further research to optimise training programmes to make them more effective and accessible to groups of patients of all ages.

The results of our study showed that the number of deliveries and the route of delivery had no significant effect on the incidence of urinary incontinence, either in premenopausal (BMGE) or postmenopausal (PMGE) women. Natural deliveries are often identified as major risk factors for urinary incontinence [13, 14]. The study by Liu et al. [8] involved 255 women who were divided into a study group with stress urinary incontinence (n = 105) and a control group without stress urinary incontinence (n = 150). This study showed that vaginal delivery significantly increased the risk of maternal stress urinary incontinence [15], which was not confirmed by our study. However, the number of women in our study was much smaller than in the study by Liu et al. [8]. It is possible that other factors such as lifestyle, physical activity or access to postnatal rehabilitation may mitigate the potential negative effects of multiple births or mode of delivery. However, further research is necessary to better understand these relationships and confirm our assumptions. Our study also shows that pelvic type and postural pattern had no significant effect on the incidence of urinary incontinence in both premenopausal (BMGE) and postmenopausal (PMGE) women. There is a lack of studies in the literature directly analysing the association between pelvic type and postural pattern and urinary incontinence in the female population, particularly taking into account the breakdown by life stage, such as premenopausal and postmenopausal. Further research is required to better understand the potential relationship between pelvic type, postural pattern and urinary incontinence in different age groups. Pelvic type or postural pattern has been described in terms of dysfunction: musculoskeletal, cardio-pulmonary system and visceral system. A limitation of our study was that the group of women participating was too small and there was no control group of pre- and postmenopausal women.