Summary

The KOS-MI program has transformed cardiovascular care in Poland, significantly improving patient outcomes up to 3 years after myocardial infarction by integrating comprehensive secondary prevention strategies. This study provides a thorough analysis of all program components, demonstrating how these measures contribute to better health results, including reduced low density-lipoprotein levels, improved left ventricular ejection fraction, and overall enhanced cardiovascular health. While these outcomes highlight the program’s success in optimizing post-infarction care, some parameters showed less consistent progress, indicating areas that require further refinement to ensure uniform benefits across all patients. These findings confirm the program’s effectiveness while emphasizing the need for continuous improvements to maximize long-term treatment success and further enhance cardiovascular care quality.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are still the leading cause of death worldwide. In Europe, they are responsible for 45% of deaths among women and 39% among men [1]. The continuous development and availability of interventional cardiology have significantly improved in-hospital mortality. Still, the overall 1-year mortality of patients with myocardial infarction (MI) remains high, at 17.3% (8.4% in-hospital mortality, 9.8% post-discharge mortality) [2]. Frequent medical supervision and patients’ participation in cardiac rehabilitation are the main determinants that reduce the mortality of patients after MI [3–5]. Compliance with medical recommendations, including adherence to pharmacotherapy, also reduces the frequency of recurrence of cardiovascular events [6]. The Coordinated Care Program in Patients after Myocardial Infarction (KOS-MI) was introduced in Poland in 2017 as a coordinated and unlimited secondary prevention measure [7]. It applies to all patients who consent to participate in the program after MI. The results of the annual survival analysis have been previously published. The participation of KOS-MI translated to a reduction in mortality rate between 29 and 38% [8, 9]. The 3-year outcomes showed a relative risk reduction of 25% in major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) (p = 0.008) and 38% in mortality (p = 0.008) respectively [10]. However, there is no detailed analysis of the goals of secondary prevention measures.

Aim

Our study aimed to analyze patients’ compliance with secondary prevention measures recommended in the KOS-MI Program and associated outcomes at 1-year and 3-year follow-up.

Material and methods

This retrospective, single-center observational registry included 331 patients enrolled in the KOS-MI Program at the Cardiology Clinic between November 1st, 2017, and November 14th, 2018.

Principles of KOS-MI

The KOS-MI Program is a guaranteed benefit introduced by three Regulations of the Minister of Health. This benefit is provided by healthcare facilities based on contracts concluded with the National Health Fund (NFZ) [11]. Patients were enrolled in the program at the time of hospital discharge following myocardial infarction. Participation in the KOS-MI Program includes diagnosis of MI and therapy by clinical indications (Module I), in-hospital or ambulatory cardiac rehabilitation (CR) (Module II), implantation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy in eligible patients (Module III), and 12-month outpatient specialist care (Module IV) [7, 12]. Patients who consented to participate in the program had a screening visit 1 week after discharge, tailored to their clinical needs and any planned staged revascularizations. Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) began within 2 weeks after discharge. Patients with severe conditions, such as those with heart failure, reduced ejection fraction (LVEF), or complicated myocardial infarction, were referred for inpatient rehabilitation. Other qualifying factors included type 1 diabetes, a history of coronary artery bypass grafting, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Patients with less severe conditions underwent outpatient rehabilitation. All participants completed a 6-minute walk or treadmill test as part of their CR assessment and attended follow-up visits with a cardiologist. Echocardiography performed 3 months after discharge assessed eligibility for implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) or cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). The program concluded with a final visit summarizing the patient’s condition. This included laboratory tests (e.g., LDL levels, glycated hemoglobin or fasting glucose), blood pressure, body mass index, and an electrocardiogram. The questionnaire also addressed smoking habits and planned myocardial revascularizations, alongside evaluations of angina severity (CCS classification) and heart failure symptoms (NYHA classification).

Definitions

MI was defined in accordance with the Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction [13]. Chronic kidney disease was characterized by an estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) rate < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, based on established guidelines [14]. Coronary angiography was performed following standard procedural protocols [15]. The choice of stent type used was at the operator’s discretion. Post-MI pharmacotherapy was prescribed according to the European Society of Cardiology recommendations [16]. LVEF was evaluated through transthoracic echocardiography using the modified Simpson’s biplanar method, as recommended in echocardiography guidelines [17].

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the assessment of LDL cholesterol and LVEF levels among patients who completed the KOS-MI program. In accordance with the program’s established time points, LDL was assessed at admission and at the 1-year follow-up visit, reflecting long-term lipid management. LVEF changes were evaluated at admission and at the 3-month follow-up visit.

The secondary endpoints included the frequency of the combined MACCE endpoint – defined as all-cause mortality, MI, repeated revascularization, and stroke and its individual components, as well as recurrent hospitalizations for heart failure at 1- and 3-year follow-ups.

Additionally, we analyzed all supplementary data included in the balance visit forms within the KOS-MI program, which encompassed:

percentage of patients who completed rehabilitation,

percentage of patients participating in ambulatory and stationary rehabilitation,

percentage of patients undergoing subsequent planned myocardial revascularizations,

percentage of patients using tobacco products after 1 year,

percentage of patients with hypertension under control (< 140/90 mm Hg),

glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) or average glucose level (depending on the test performed for each patient),

body mass index (BMI) value,

evaluation of Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) angina severity,

assessment of the severity of heart failure symptoms according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification.

Baseline medical information was collected from the hospital’s internal system. Data from patients’ participation in the KOS-MI Program were collected from the medical records in the KOS-MI clinic’s patient files. Long-term observation data were obtained from the National Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes based on NFZ data.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Categorical data were presented as absolute numbers and percentages. The dependent t-test was used for paired samples. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. Data were compared using a box-and-whisker plot. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica (v. 10; StatSoft. Inc. USA) and MedCalc v. 18.5 (MedCalc. Belgium).

Results

In total, 331 patients were enrolled in the KOS-MI program, and 262 (79.2%) completed it. A total of 69 (20.8%) patients left the program, whereas 26 (37.7%) individuals successfully completed rehabilitation (Figure 1).

ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was diagnosed in 46.2% (n = 121) of cases, heart failure was reported in 1.5% (n = 4), and 91.2% (n = 239) underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). A detailed summary of baseline patient characteristics at admission and angiographic data is presented in Table I.

Table I

Baseline patient characteristics on admission and patient angiographic data

According to their overall condition during their hospital stay, including LVEF value, patients were assigned to one of two types of rehabilitation. For patients in stationary rehabilitation, which comprised 56.1% (n = 147) of the group, the 6-minute walk test was conducted, and they achieved an average distance of 306 ±110.6 m. The remaining 43.9% (n = 115) participated in daily rehabilitation and underwent an exercise test, where their results improved from an average of 6.7 ±1.7 MET before rehabilitation to 8.5 ±1.5 MET after rehabilitation (p < 0.001).

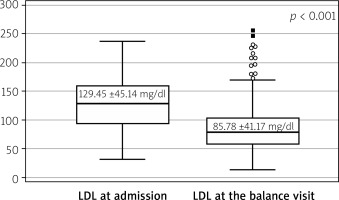

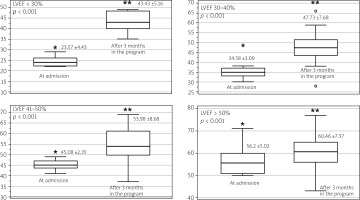

Findings for the primary endpoint indicated a statistically significant reduction in LDL after 1 year (Figure 2). Nevertheless, the LDL goal of < 55 mg% was achieved in only 19.1% (n = 50) of cases. We also observed a statistically significant improvement in LVEF after cardiac rehabilitation. The analysis of subgroups of patients with LVEF < 30%, LVEF 30–40%, LVEF 41–50%, and LVEF > 50% showed that in each group there was a significant benefit (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Ejection fraction changes during the KOS-MI Program were assessed 3 months after enrollment, including an analysis of changes in specific subgroups over this period

*LVEF at admission. **LVEF after 3 months in the program.

Data on secondary endpoints from 1-year and 3-year follow-up, assessing statistical significance for MACCE, death, and MI are presented in Table II. The results for additional assessment, comprising components of the coordinating and balance visit form, were as follows: BMI at the beginning was 27.5 ±4.6 kg/m2, and at the end of the program, 27.6 ±4.9 kg/m2 (p = 0.9); at the end, glycated hemoglobin was 6.15 ±1.13%, and average glucose level was 132.4 ±31.8 mg/dl. The checkbox indicating blood pressure < 140/90 mm Hg on the balance visit form was marked for only 35.2% (n = 92) of patients. Nicotine addiction was documented in 7.6% (n = 46), while 1.5% (n = 4) experienced an ischemic event during the KOS-MI program, and 2.7% (n = 7) were hospitalized due to heart failure decompensation. Most patients in the KOS-MI Program were classified as NYHA I (88.9%, n = 233) and CCS I (91.2%, n = 239), indicating mild heart failure symptoms and stable angina. A minority of patients had more advanced symptoms, with 8.8% (n = 23) in NYHA II and 8.0% (n = 21) in CCS II. None of the patients presented symptoms classified as NYHA IV or CCS IV. The drug adherence to statin was 99.6%. Patients differed in the dose and type of statin intake (Table III). In 21.4% (n = 56) of cases, adding ezetimibe was necessary.

Table II

One- and three-year outcomes. Follow-up 93.89%

Table III

Pharmacotherapy of patients in the KOS-MI Program upon discharge

Discussion

Previous studies of the KOS-MI program mainly concentrated on survival rates and MACCE occurrences. For instance, one analysis reported a 1-year prevalence of all-cause death, recurrent myocardial infarction, and stroke at 10.6% [18]. Another study, which included heart failure hospitalizations in the MACCE definition, observed a prevalence of 11.3% [19]. In contrast, our research provides a thorough and unique evaluation by examining all the parameters assessed within the program. Although conducted on a smaller group, this analysis offers valuable insights and a thorough evaluation of the program’s effectiveness in managing post-MI care in different areas. It highlights the program’s noteworthy achievements while pointing out elements requiring further improvement.

Effective lipid management is essential for secondary prevention, particularly in high-risk patients following ACS [20]. However, achieving the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommended target of < 55 mg/dl remained challenging, with only a minority of patients reaching this goal [3]. A standout accomplishment of the program was the notable decrease in LDL cholesterol levels, dropping from 129.5 mg/dl to 85.8 mg/dl during the 1-year follow-up (p < 0.001). Earlier analyses within the program revealed similar trends, with LDL cholesterol levels decreasing from 119.3 ±47.1 mg/dl to 83.9 ±35.1 mg/dl after 12 months [21]. Data from a cohort of 1,499 patients showed that only 20.4% reached the LDL target, while 26.9% achieved a ≥ 50% reduction in baseline levels. Among these patients, 28.7% were prescribed high-intensity statins, and 41.5% received combination therapy with statins and ezetimibe [22]. This enhancement highlights the program’s effectiveness in lipid profile management and reflects the importance of adhering to the recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology and the Polish Cardiac Society to improve outcomes in high-risk patients through intensive lipid-lowering therapies.

In the population included in our research, 55.7% received rosuvastatin, and 43.9% received atorvastatin, with ezetimibe added to the treatment regimen for 21.4% of participants. Despite these measures, the prescribed statin doses were often insufficient, with the majority receiving moderate doses and only a small percentage on high-intensity regimens. Intermediate statin dosages typically reduce LDL cholesterol by approximately 30%, while higher doses can achieve reductions of around 50%. Clinical trials have consistently demonstrated that early and intensive LDL lowering, particularly with high-dose statins, significantly reduces cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality [23, 24].

While these results reflect the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies within the program, adherence remains a critical factor in sustaining long-term benefits. Coordinated care within the program significantly reduced the risk of statin discontinuation, with a relative risk reduction of 51% among high-risk post-AMI patients. However, an 11% discontinuation rate highlights the need for continued efforts to support patients and address barriers to adherence [25]. This underscores the importance of integrating structured follow-up and patient-centered strategies to maintain the positive outcomes achieved through initial interventions.

Beyond lipid management, the program demonstrated significant improvements in cardiac function. The mean LVEF increased from 48.4% to 56.1% (p < 0.001). The most pronounced gains were observed in patients with severe baseline dysfunction, with LVEF improvements of nearly 20% in those with LVEF < 30%. For patients in the 30–40% range, the increase was approximately 13%, while smaller but still significant gains were noted in higher LVEF groups. Additionally, functional capacity improved significantly, as measured by metabolic equivalents (METs) during the rehabilitation program’s treadmill testing. METs increased from 6.7 ±1.7 to 8.5 ±1.5 (p < 0.001). These improvements are clinically meaningful, as a 1-unit increase in METs correlates with a 19% reduction in cardiovascular mortality and a 17% reduction in all-cause mortality [26].

Despite some achievements, several parameters exhibited less consistent progress. In the overall cohort, the mean HbA1c at the last visit was 6.15 ±1.13%, with an average glucose concentration of 132.35±31.8 mg/dl. These values suggest partial improvement in glycemic control; however, a closer look at the subgroup with diabetes (n = 57; 21.8% of the study population) reveals that only 49% of those patients reached an HbA1c level below 7%. This highlights the necessity for more focused interventions in this at-risk population. A similar pattern was observed in blood pressure control. At the final follow-up, only 30% of patients achieved values below 140/90 mm Hg. While white-coat hypertension might have contributed to these results, the well-established risks associated with inadequate blood pressure management underscore the urgent need for more effective strategies. Therefore, regular monitoring and individualized treatment adjustments are essential to bridging these gaps in care.

Lifestyle interventions demonstrated both achievements and ongoing challenges. While smoking cessation indicated promising results, with 54% of smokers quitting successfully – a significant outcome that showcases the program’s influence on behavior – there were no notable decreases in BMI. This highlights the necessity for more organized and rigorous approaches to tackling obesity, which is a critical modifiable risk factor population.

These findings highlight the need for a more precise and multifaceted approach to secondary prevention. Education and targeted prevention efforts are among the most effective and economical strategies for reducing the burden of cardiovascular diseases [27]. Similar conclusions were drawn by Banach et al., who emphasized the importance of addressing multiple risk factors simultaneously, including lipid levels, glucose control, blood pressure, and smoking cessation. Advancements in innovative therapies and digital health tools present valuable opportunities to enhance patient adherence and optimize outcomes. While these approaches align with the broader objectives of the KOS-MI program, there remains significant room for improvement, particularly in secondary prevention. Refining and expanding these initiatives is essential to ensure effective management of diverse risk factors and meaningfully reduce cardiovascular disease burden [28].

A key factor in the program’s success was the high rate of participation in rehabilitation. Our previous analysis revealed that 90% of KOS-MI participants engaged in rehabilitation, while the control group had only 22.7% participation (p < 0.001) [10]. This significant difference highlights the KOS-MI program’s comprehensive approach, where rehabilitation is treated as an essential element rather than just an optional aspect of post-MI care. By incorporating structured rehabilitation into the patient pathway, the program has greatly improved clinical outcomes and helped patients attain meaningful enhancements in their quality of life. However, despite this overall success, certain challenges affecting participation were observed. Among patients who discontinued the program, the most common reasons included failure to attend scheduled follow-up visits, often without providing a specific explanation. In some cases, participation in cardiac rehabilitation was limited by logistical barriers, such as lack of transportation or limited availability of nearby facilities. These difficulties emphasize the importance of addressing structural and organizational factors when evaluating the feasibility and broader implementation of the program.

Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System (AOTMiT) findings underscore the significance of the KOS-MI program. Their 2016 report, “Care after Myocardial Infarction” (No. AOTMiT – WT-553-13/2015), analyzed data from 28 countries, representing a total population of approximately 600 million. The report highlighted notable disparities in cardiac rehabilitation programs, noting that only 14 countries, including Poland, provided both inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation in the early post-hospitalization phase [29, 30]. Initiatives such as KOS-MI seek to address these gaps by integrating medical management, rehabilitation, and psychosocial support to improve overall care outcomes.

Patient feedback highlights the KOS-MI program’s success in enhancing health and wellness overall. The program achieved an impressive 100% adherence to medication and led to improved patient outcomes through ongoing medical care, consistent interaction with healthcare providers, and psychological support during rehabilitation. A survey conducted by Feusette et al. with 150 participants revealed that 50.6% rated their health as “very good”, while 74.7% reported positive health effects from participating in the program [31]. These findings emphasize the program’s holistic approach in tackling both physical and emotional aspects of recovery. Previous research has consistently shown that cardiac rehabilitation and outpatient care are essential for improving prognosis, reducing cardiovascular risks, and enhancing life quality for patients following a myocardial infarction [9, 10].

When the KOS-MI program was first implemented in Poland, it was available in 42 centers. That number has since increased to 68 [32]. Despite this growth, availability remains limited, particularly as the incidence of acute coronary syndrome rises. Data from the NFZ show an increase in acute coronary syndrome cases from 69,500 in 2016 to 76,000 in 2019.

This study has several limitations. As a single-arm, observational analysis, it does not allow for causal inference; observed improvements in LDL cholesterol and LVEF, particularly in patients with initially low values, should be interpreted with caution, as they may result from natural variation or unmeasured factors. The absence of a control group – due to the program’s integration into routine care – further limits the ability to isolate the effect of the intervention. Additionally, the small sample size and short follow-up reduce the generalizability of the findings and prevent conclusions about long-term outcomes. Despite these constraints, the results offer meaningful real-world insights and highlight areas for future, controlled research.

Conclusions

The KOS-MI Program demonstrated effectiveness in post-MI care, with low rates of adverse events at one and 3 years and notable improvements in LVEF, particularly in patients with baseline values below 30%. However, despite a significant reduction in LDL levels, 80.9% of patients failed to meet target values, highlighting the need for more effective lipid-lowering strategies. Some clinical parameters showed less consistent progress, suggesting areas that require further refinement. To optimize long-term outcomes, future efforts should focus on improving patient adherence, addressing barriers to engagement, and implementing personalized interventions based on individual risk profiles.