Introduction

Malignant tumors constitute a growing social, health and economic problem for Polish society. The scale of the problem is reflected in the numbers of new cases (167,500), deaths (101,400) and over 1,170,000 people living with cancer at the end of the second decade of the 21st century. It is expected that for every 100,000 inhabitants of the Polish population in 2018, 436 people were diagnosed with cancer and 3051 were living with a cancer diagnosis in the previous 10 years [1].

In 2019, the National Cancer Registry received 85,559 reports of malignant tumors in men, and 85,659 in women [2]. The most common cancers in men in 2020 were: prostate (20%), lung (16%), colon (7%) and bladder cancers (7%). In women, these were: breast (24%), lung (10%), corpus uteri (7%), colon (6%), ovarian (4%) and thyroid cancers (4%) [3, 4].

Currently, it is estimated that 2/3 of patients with a cancer diagnosis are eligible for systemic treatment. Therefore, ensuring proper intravenous access becomes an important element of chemotherapy as most drugs are administered parenterally and are locally irritating and toxic [5]. Extravasation refers to the accidental leakage of a drug from the blood vessel into the surrounding tissues during intravenous administration. It can indeed cause localized pain, swelling, erythema (redness), and in severe cases it may lead to skin damage such as blackening or blistering, as well as the formation of ulcers [6–8].

Chemotherapy drugs are known for their potential to cause tissue damage if they escape the blood vessels. When extravasation occurs, it can result in serious complications, and managing these cases may involve surgical procedures such as debridement (removal of damaged tissue) and skin grafting to promote healing and prevent infection [9].

To address the challenges associated with chemotherapy and the potential complications of extravasation, the use of central venous access devices, such as ports, is often considered. These devices provide a more reliable and long-term solution for administering intravenous infusions [10, 11].

A port is a small medical device implanted under the skin, usually in the chest area. It is connected to a catheter that is inserted into a large vein, allowing healthcare providers to access the bloodstream for the administration of medications, such as chemotherapy, without relying on peripheral veins. Ports are particularly useful when peripheral vein access becomes difficult, as is common in patients undergoing repeated or prolonged treatments.

The decision to insert a port is typically made after considering a range of factors, including the type and duration of treatment, the patient’s overall health, and the feasibility of using peripheral veins. While ports offer advantages in terms of safety and convenience, their insertion involves a minor surgical procedure and care.

Ultimately, the choice of intravenous access depends on the specific circumstances of each patient and their treatment plan, with the goal of providing the most effective and least invasive method for administering medications while minimizing potential complications [12, 13].

Objective, research questions and hypotheses

The objective of the work was an analysis of the reasons for removing vascular ports in patients hospitalized in the departments of Surgery, Chemotherapy and Gynecological Oncology in Poznań, Poland. Oncological patients treated over a 24-month period were analyzed from the point of view of the number of ports inserted and complications related to oncological treatment.

The basic research questions concerned the locations of cancers and the reasons for removing a port. In order to answer these questions, several research hypotheses were put forward. Pursuant to the standard inferential statistics principles, the assumption of no effect (no statistically significant difference) of the analyzed variables was adopted as a null hypothesis. Thus, each of the research hypotheses is accompanied by a corresponding null hypothesis that assumes no statistically significant association/difference. In the cases with statistical significance at p < 0.05, the null hypothesis was rejected, supporting the research hypothesis. In the cases where p ≥ 0.05, the null hypothesis was not rejected, indicating no significant relationship and thus not supporting the research hypothesis.

The following research questions and hypotheses were formulated:

Did patient age determine the location of cancers in the patients in the surgical department (excluding gynecology) in 2021 and 2022?

H0. Patient age determined the location of cancers in the patients in the surgical department (excluding gynecology) in 2021 and 2022.

Did patient gender determine the location of cancers in the patients in the surgical department (excluding gynecology) in 2021 and 2022?

H0. Patient gender determined the location of cancers in the patients in the surgical department (excluding gynecology) in 2021 and 2022.

Did patient place of residence determine the location of cancers in the patients in the surgical department (excluding gynecology) in 2021 and 2022?

H0. Patient place of residence determined the location of cancers in the patients in the surgical department (excluding gynecology) in 2021 and 2022.

Did the specific type of the department (and thus the kind of cancer) determine the reason for removing the port in 2021 and 2022?

H0. The specific type of the department (and thus the kind of cancer) determined the reason for removing the port in 2021 and 2022.

Did patient place of residence determine the location of cancers in the patients in the gynecological department in 2021 and 2022?

H0. Patient place of residence determined the location of cancers in the patients in the gynecological department in 2021 and 2022.

Material and methods

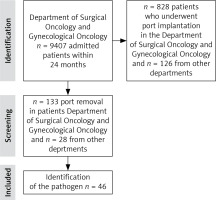

The Surgical Oncology and Gynecological Oncology departments received 9,407 patients over a 24-month period. The port insertion procedure was performed in 828 (8.8%) admitted patients. Patients after port implantation were observed for complications during the administration of systemic treatment with cytostatics at the Chemotherapy and Gynecology departments. Patients were deemed eligible for the port implantation procedure based on Polish Union of Oncology guidelines (Fig. 1).

First, the number of patients who had undergone port implantation was obtained from the procedure code in the IT database. In this way, 954 patients were identified. The results were then analyzed in terms of indications for the procedure, the department where the procedure was performed, gender, and reasons for removing the port.

All the oncological patients had been deemed eligible for implantation due to their long-term oncological treatment, to protect peripheral veins and ensure better comfort of treatment. The patients from other departments were deemed eligible for this procedure due to the specific character of the treatment, e.g. pulmonary indications, parenteral nutrition, and other.

At the next stage, those patients who had undergone port removal were identified based on the same database procedure code, providing 313 patients from the chemotherapy and oncology departments and 28 patients from other departments. Then, medical histories of all the patients were verified in the IT system, and the records from the hospital Microbiology Laboratory were analyzed to identify pathogens that had been isolated from the port tip following its removal.

The microbiological examination was aimed at detecting the pathogenic microorganism in the clinical material and determining its sensitivity to antibiotics (antibiogram). Microbiological testing is a multi-stage process. The first stage of the study was cultivation of the microorganism. Most aerobic microorganisms need 18–24 hours of incubation to grow; however, anaerobic bacteria, fungi, and some aerobic bacteria may require prolonged incubation, up to 48–96 hours or even several weeks (dermatophytes). The second stage of the study included the isolation and identification of the microorganism using manual, semi-automatic or automatic tests. The purpose of the third stage of the test is to determine the microorganism’s sensitivity to drugs, classifying the microorganism into one of three categories: sensitive, moderately sensitive, and resistant. The final positive test result is issued when the process of identifying the microorganism and its sensitivity to drugs is completed, while the final negative test result covers the time in incubation when no microbial growth is observed (usually 24–48 hours).

The analysis identified 46 vascular port infections over the two years.

Depending on the nature of the variables and the sample size, the contingency coefficient was used as a measure of the strength of the relationship. To test differences in means, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used, along with determining the statistical significance of the obtained results.

All analyses were performed using the statistical program SPSS v28.

Examinations were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and accepted by the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Poznań. They were registered under the number 904//23.

Results

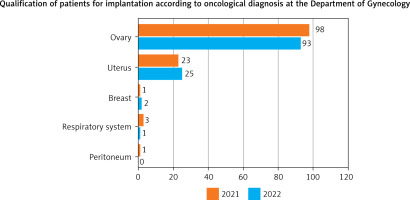

Figure 2 shows the percentage of admissions to individual departments in 2021–2022. Overall, 77% were admissions to the Department of Gynecology, which reflects the specific focus of the department, while 23% were admissions to the Department of Surgical Oncology.

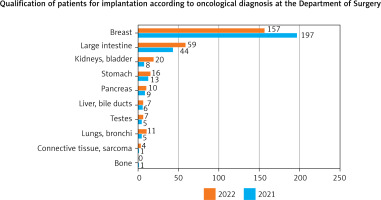

Figure 3 illustrates the proportion of patients admitted to the Department of Surgery with particular types of tumors over a 24-month period.

Fig. 3

Division of tumors in patients qualified for a vascular port in Department of Surgical Oncology (n = 580)

The most dominant reason for port removal is the conclusion of systemic therapy using cytostatics, in which case, after the decision of the attending physician, patients were referred to the ward for port removal, comprising 82.7% of all removals. More of these procedures were performed in 2022 with 163 cases on all of the wards combined, while the previous year had only 119 port removals. The remaining removals were related to: obstruction, incorrect insertion technique, suspicion of infection and thrombosis, or suspicion of hematoma, as well as in some cases the exclusion of infection, which was very important in patients treated in the transplant (bone marrow) department of the local hospital from the point of view of further therapy (Table 1).

Table 1

Number of vascular ports removed in 2021–2022

Table 2 shows the pathogens cultured from material collected from patients reporting adverse symptoms during therapy. The greatest number of cultures, as many as 24, contained microorganisms of the genus Staphylococcus spp. (52.2% of all infections), followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa with 4 cultures (8.7%), and 5 cultures (10.8%) were bacteria from the Klebsiella genus, cultured from the material that was delivered to the laboratory. Two cases of each were cultured: Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, Citrobacter (freundii + koseri) and Corynebacterium bovis (4.3% of all infections each).

Table 2

Types of microorganisms cultured from microbiological cultures

In the last row of the table, a negative culture was entered. Although the clinical picture of the patient indicated sepsis, the attending physician decided to remove the implant for the sake of the patient being treated in the transplant unit, and this case was classified as an infection.

The result of the contingency coefficient is statistically significant. This means the presence of a statistically significant relationship between the analyzed variables. The main reason for port removal in the chemotherapy department was completion of treatment. The main reason for port removal in the gynecology ward was infection (Table 3).

Table 3

Reasons for vascular port removal in 2021–2022 by department

Table 4 lists the main symptoms that occurred during systemic therapy and that resulted in the removal of the implants. The main symptom in 10 patients was fever and chills, with simultaneous purulent discharge from the wound and redness around the implant – the causes of complications related to the procedure of therapy using an intravascular port.

Table 4

Symptoms and causes of vascular port removal

The number of irregularities observed in 2021 is noteworthy in comparison with 2022. This is due to the fact that the information for this study was collected from nursing and medical descriptions contained in the hospital Esculap system.

The average age of the patients in 2021 was 58.76 with a standard deviation above 22% of the average value, which indicates an average diversity of age. The highest average age was recorded among patients diagnosed with kidney cancer (mean ±SD [72.22 ±2.682]), liver cancer (mean ±SD [68.40 ±5.550]) and rectal cancer (mean ±SD [67.26 ±10.700]). For 2022, the average age of patients was 58.94 with a standard deviation above 21% of the average value, which indicates an average diversity of age. The highest mean age was recorded among patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer (mean ±SD [69.50 ±6.916]). The differences were statistically significant (p = 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5

Cross tabulation group age of patients vs. diagnosed tumor site

In the case of women treated in the surgical oncology department, the average age in 2021 was 77.23 and in 2022 61.63. The most frequently diagnosed cancer in both 2021 and 2022 was ovarian cancer (mean ±SD [81.06 ±198.645] and mean ±SD [62.01 ±13.165], respectively). The differences were not statistically significant (Table 6).

Table 6

Age vs. tumor site in gynecological surgical departments in 2021 and 2022

The place of residence determined the tumor site in gynecological surgical departments in 2021 (Table 7).

Table 7

Place of residence vs. tumor site in gynecological surgical departments in 2021 and 2022

The result of the contingency coefficient is statistically significant. This means the presence of a statistically significant association between the analyzed variables. The differences are mainly related to tumors in the rectum, pancreas and stomach in men, and in the breast in women (Table 8).

Discussion

The use of vascular port implantation in oncological patients has made a significant positive impact on their comfort and overall quality of life during systemic treatment [14, 15]. Patients presenting to hospital wards for subsequent chemotherapy courses do not have to be subjected to painful and difficult installations of peripheral cannulas on blood vessels already damaged by chemotherapy treatment.

It is very important in the process of oncological treatment that therapy using cyclic intravenous infusions is carried out safely using an access that will be optimal for the patient [16, 17]. A patient undergoing debilitating cancer therapy should experience only minimal discomfort from the insertion and removal of the Huber port needle during a long period of treatment counting at 2–3-week intervals in cycles of 10 or even 15 times. Any stress and pain associated with oncological therapy should be minimized, which is why installing an implant during therapy is very effective and important at the beginning of treatment. The physician planning the therapy should, immediately after making the decision about oncological treatment, propose or convince an undecided patient to consider a variant of therapy using an implant, as a better solution for both the patient and nursing staff.

Some cytostatic group drugs require administration of long-term intravenous infusions, even for several days. Fluorouracil is an excellent example of such treatment, which lasts up to three or four days at a time, meaning that administration of the drug requires hospitalization. An alternative is to use a so-called infusor with the drug, which is inserted into the established port access, allowing the patient to stay at home while the drug is being administered [18].

Available literature shows that researchers are focusing more often on the medical and economic evaluation of the use of ports in therapy [19, 20]. Publications are more often concerned with factors such as complications, infections and costs, but in recent years there has been increasing interest in the opinions and experiences of using implants from the perspective of the patients themselves [21]. Assessing patients’ knowledge of care, guided drug infusion, or level of satisfaction with regard to the use of the implant vs. with a peripheral cannula are increasingly being studied [22].

Similar conclusions confirm the results of a study published by Babiarczyk et al. [23] on a group of 112 patients undergoing oncology treatment. The study found a 67.9% high level of satisfaction and 27.7% medium level of satisfaction with individual satisfaction characteristics of vascular port use.

Education of patients by nursing staff is very important in the treatment of patients in wards and clinics where cytostatic treatment is administered. They can learn and dispel any doubts regarding the therapy during numerous and lengthy visits. Patients who are in the wards or in outpatient clinics very often exchange insights with other patients, so it is very important to properly educate the patients who are at the beginning of their journey to be able to count not only on the support of the doctor who provides therapy, nurses who perform the ordered treatment, and also other patients who are often treated for the same disease. Support and education at the beginning of therapy can be very important and crucial in forming a positive outlook in further treatment.

Another key and important aspect in the treatment of vascular port implantation in patients qualified for this procedure is the scheduling order of the procedure in the operating theater. A patient who is admitted to the ward for implant placement should be scheduled first, before other procedures. This is very difficult from the point of view of operating theater logistics, which poses huge challenges for management. The technique of implant insertion for the operator, if not facing technical difficulties, is quite simple, and the dexterity of those involved in the procedure is the basis of preventing later infections.

An in-house study was conducted to test and evaluate at what level infections associated with implant therapy occur. The medical records of patients who had undergone implantation in the Esculap hospital IT system over a period of 24 months were analyzed. The study included 954 patients by the department from which they were referred for the procedure and 341 patients who had their implants removed.

The study showed that in 82.7% of cases, the reason for removing the ports within two years was completion of the treatment, and in 13.5% it was due to infections. The remaining reasons for implant removal ranged 1.2–0.3% and included catheter occlusion, incorrect insertion, thrombosis, suspected infection or hematoma. A similar study Barwińska-Pobłocka et al. was conducted in the Department of Gynecological Oncology and Gynecological Endocrinology at the Medical University of Gdansk [24]; however, the study included 83 patients over a period of 53 months, and studied the duration of port maintenance and the incidence of early and late complications. The researchers identified 7 cases of bacteremia, constituting 8.43% of all complications.

A study was performed by Paleczny et al. [25] at the Bielsko-Biala City Hospital, where 220 ports were inserted over a 5-year period (2008–2013). The authors cite technical difficulties during insertion as the most common early complication (5.7%), with bacteremia (1.5%) being one of the complications found at this hospital.

Other publications Nicpoń et al. [26] indicate implant infection at the level of 4.1% of all late complications. The authors indicated that about 60% of infections are caused by skin-colonizing bacteria, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella spp., Acinetobacter spp., which partly coincides with the results of the study cited in the authors’ own paper. The cultured microorganisms come from the skin, and colonize the port area, which can in turn cause infection by too short a time between disinfection and the insertion of the Huber needle into the port. The second cause could be microorganisms colonizing the skin of the hands. Staff may not have properly disinfected their hands, and by touching the port tip, may have contributed to the transmission of bacteria to the port.

Moreover, it should be emphasized that the pathogenic factors of infections may differ between individual medical facilities. It is absolutely necessary to constantly monitor infections related to the performance of specific procedures, register the occurrence of alarm microorganisms in a given ward, and cooperate with the clinical microbiology department in order to determine the profile and drug susceptibility of pathogens [27–29].

The publication by Misiak [30] drew attention to routine antibiotic prophylaxis administered before or after the implantation procedure, and noted that it is not necessary, as the results of its administration in the perioperative period are questionable. The author highlighted the problem of increasing resistance as well as the risk of side effects to the drug used, and therefore concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis should be used only in exceptional cases, e.g. in patients with low leukocyte counts.

The examined period considered in the study includes the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was a difficult period not only for patients treated in health care facilities, but also for staff working in the departments, because on one hand, procedures were introduced to prevent the spread of COVID-19, thus contributing to an intensified regime, while on the other, the pandemic caused an absence of medical staff, which could have contributed to reduced vigilance caused by fatigue and overwork in individual departments. The study did not undertake an analysis of staff absenteeism during the studied period; however, the pandemic significantly affected the work of all hospital departments, but did not reduce the number of patients treated because oncological treatment was named a priority therapy.

The procedure for removing a port should be undertaken by the attending physician immediately after the completion of treatment, so that the patient returns to full function, with upper limb movement as well as aesthetic comfort, which is important not only to women. Completion of oncological therapy and implant removal will not involve a visit to the hospital or clinic to flush the vascular port, and there will be no risk or danger of infection during this procedure.

Many authors emphasize that following their own recommendations and those of societies, including the Polish Society of Epidemiological Nurses [31], has a significant impact on the awareness of preventing infections related not just to therapy using vascular ports but also to therapies that use other catheters and cannulas. All recommendations emphasize that the proper technique of inserting and guiding cannulae [32] and correct technique of disinfecting the skin before cannulation [32, 33], such as disinfecting the ends of tubing [32] and disinfecting hands before each contact during therapy, are essential [31]. This is supported by the results of a study conducted by Dziewa published in 2016, examining indicators of the quality of nursing care in the prevention of vascular line infections [34]. The author identified the causes of vascular line infections, such as insufficient/improper disinfection of the insertion site, and additional or unnecessary manipulation after disinfection.

Therefore, based on the literature reviewed, in order to reduce the incidence of treatment-related complications, it is necessary to introduce systemic measures in accordance with the principles of good practice that significantly improve the awareness and knowledge of the personnel caring for patients.

It should also be emphasized that patients living in towns or villages report to local health centers to have their ports flushed; the staff working there are usually not familiar with such a procedure or do not have Huber needles, as they are not available in pharmacies in smaller towns. It is important that the nursing staff from smaller centers working in primary care, nursing homes and others, are trained in the care of vascular ports so that flushing every 4 or 6 weeks can be performed at the patient’s place of residence. The patient would then not have to travel or be transported to the facility for such procedures [35, 36].

Vascular ports play a key role in therapy, especially among patients with an oncological diagnosis and scheduled for lengthy chemotherapy treatment. The use of this type of solution for patients undergoing oncological treatment makes it possible to reduce the risk of complications related to the therapy, which is not only painful but also irritating to venous vessels, especially peripheral ones. A properly cared for vascular port makes it possible to avoid painful complications that can significantly prolong therapy.

Conclusions

In the period January 1, 2021 – December 31, 2022, 828 vascular ports were inserted in 9407 patients in the departments of Surgery and Gynecological Oncology, accounting for 8.8% of hospitalizations in these departments.

During the period under study, 46 complications related to oncological treatment caused by microorganisms were found, which contributed to the removal of the ports because of the cause of symptoms of infection.

Over the course of the two years, ports were found to be contaminated by pathogenic microorganisms living mainly on the patients’ skin as well as on the hands of the staff inserting the Huber needle into the port and administering systemic treatment.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strengths of the study are the large number of patients who were analyzed and the extension of corroborating experience useful for establishing scientific evidence. On the other hand, the authors did not make any comparisons with results from other leading health care institutions (including foreign institutions). The next step in future research will be to pursue changes, including education, to improve patient safety and reduce infection rates. In addition, the authors will compare infection rates between ports in hospital and outpatient settings.