Introduction

One of the global health challenges are the antibiotics resistance, it includes the relationship between bacterial genes and environment. Despite the many obstacles to the flow of genes and bacteria, due to the low protective ability of bacterial infections and treatment resulting from the acquisition of pathogens, there are new resistance factors of other types [1, 2].

It is necessary to prevent infectious diseases because pollution and the incorrect use of antibiotics causes an increase in the incidence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial (ARB) strains. Nature has provided solutions for every disease facing humanity. Plants and their biologically active substances play an important role in treating many diseases [3].

Several critical illnesses are brought on by multidrug-resistant strains of pathogens such as Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [4–6]. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria strains can cause various infections, such as gastritis, food poisoning, urinary tract infections, and encephalitis [7, 8].

Due to the current constraints in treating these conditions with available medications, it is estimated that they will surpass cancer as the primary cause of death by the year 2050. This is because conventional antibiotics may not effectively combat infections caused by ARB [9]. Antimicrobial resistance has been recognised as an important threat to public health systems worldwide, not just in developing countries. Drug-resistant microbial infections cause 23,000 deaths worldwide every year, including in developed countries like the United States. Similar facts exist in Europe, but they are much greater in developing countries of Asia, such as India, Latin America, and Africa [10].

Due to diminishing antimicrobial discoveries by the major pharmaceutical companies, the development of new antibiotics has been declining rapidly over the past few decades. Finding new alternatives, such as those derived from medicinal plants, is therefore of interest. Beneficial phytochemicals found in medicinal plants can be utilised in the prevention of disease and treatment of various ailments across the globe [11]. In addition, around three-quarters (80%) of the Arab population uses herbal medicine for treatment and prevention [12].

The bioactive compounds in plants generally have anti-inflammatory [13], cardioprotective, anti-carcinogenic [14], antioxidant [15], antiseptic, antibacterial, and antifungal properties [16].

Artemisia herba-alba (AHA) (“desert wormwood” in English; “sheeh” in Arabic) is a medicinal and highly aromatic dwarf shrub that is typical of the steppes and deserts of North Africa (Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco), the Middle East (Egypt and Jordan), and Southern Europe (Spain), and it extends into the Northwestern Himalayas. Artemisia herba-alba plant extract has long been utilised extensively in different countries as traditional medicine, as soup or tea, to treat a variety of illnesses such as colds, coughing, intestinal disturbances, bronchitis, diarrhoea, and neuralgias arterial hypertension, and to reduce blood glucose levels [17] and inflammations caused by fungal, bacterial, or viral infections [18–21]. Due to its diverse pharmacological and biological properties, AHA exhibits various beneficial effects, including its potential in antidiabetic [22], antimicrobial [23], antitumour [24], antimalarial, antioxidant [25], insecticidal, and neurological activities [26].

This study aims to examine the antibacterial properties of various extracts (including ethanol, n-hexane, ethyl acetate, and Distell Water) from AHA, focusing on their effectiveness against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Furthermore, the study assesses their anticancer potential against breast carcinoma cell line (MCF-7).

Material and methods

Chemicals and reagents

The chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade: ethyl acetate, ethanol, and n-hexane, Mueller Hinton broth, nutrient agar, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), erythromycin, and cefotaxime, purchased from Merck (Sentmenat/Spain) and (Mireck/USA).

Collection and identification of plant material

Fresh plant AHA was harvested in Waist city between January and February 2024. The herbarium specimen was verified by Prof. Dr. Nisreen Sabbar Hishaim from the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, at the University of Diyala, Iraq.

Sample extraction

The procedure of extraction was carried out according to Ogbiko et al. [27]. The whole plant of AHA was rinsed with running water, dried under shade for 21 days, and pulverised by electric blender into powder. Then it was extracted by Soxhlet apparatus using 250 g of dried and finely ground plant in 2500 ml of solvents (ethanol, n-hexane, and ethyl acetate) at a ratio of 1 : 10 [28]. Following adding solvents, the boiling flask was placed on a hot plate at 79°C. The duration of the solvent extraction was fixed at for 72 hours, 8 hours a day. Subsequently, the extracts underwent filtering and oven drying at 45°. The dried extract was filtered, diluted in DMSO, and stored at 4°C for subsequent use.

Antibacterial activity of different solvents extracts of Artemisia herba-alba

Bacterial isolates

In this study, the antibacterial properites of AHA extract was investigated against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa American type culture collection (ATCC) 25922.

Antibacterial screening

Agar well diffusion method

The antibacterial activity of ethanol, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane extracts were tested using the agar well diffusion method according to Bauer et al. [29] against G – ve and G + ve isolates. Using a sterile swab, 100 µl of each test bacteria was briefly inoculated on Muller Hilton Agar, equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard. The wells were created using a sterilised corn borer (6 mm in diameter) into agar plates after 10 minutes of spreading. After 24 hours of incubation at 37°C. Dimethyl sulfoxide was employed as the negative control.

In vitro cytotoxicity evaluation

Cell culture

The breast carcinoma cell line (MCF-7-) and human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) purchased from the ATCC were used for the cytotoxic assay. These cells were cultured in minimum essential medium, supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml of penicillin, 100 mg/ml of streptomycin, and 2 M L-glutamine. The cultures were maintained in a controlled environment with a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C and subculture every 2 weeks.

(3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay for cell viability

The cytotoxicity of the plant extract was established using 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The cells were exposed to varying concentrations of plant extracts (0, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 µg/ml) and allowed to incubate for 24 hours. After the incubation period, test samples were extracted from the wells and replaced with 200 µl of fresh medium. Subsequently, 10 µl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline) was added and incubated for 3 hours. At the end of the incubation period, the medium in each well was aspirated, and the formazan crystals that had formed were dissolved by adding 100 µl of DMSO to each well on the plates. The plates were gently agitated until the crystals were fully dissolved. The degree of MTT reduction was promptly determined by measuring the absorbance at 570 nm [30]. The human foreskin fibroblast umbilical cell line was used as a normal cell line to assess the selectivity of extracts against these different cell lines. The cell viability percentage was calculated using the following formula:

% cell viability = (A – B)/(C – B) × 100%

where: A = absorbance of the test extract, B = blank absorbance, C = absorbance of the control.

The IC50 values, which signify the concentration at which 50% of the cells were eradicated, were derived through the examination of linear regression plots. These graphical representations illustrated the concentration of the test sample necessary to achieve a 50% reduction in absorbance in comparison to untreated cells.

Results

Effects of various solvents on extraction yield

The impact of different polarity solvents including nonpolar (n-hexane), medium-polar (ethyl acetate), and polar (ethanol) on the AHA extraction rate was studied, and the results are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1

The correlation between the zone of inhibition (mm) of American type culture collection, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, and extraction method agents

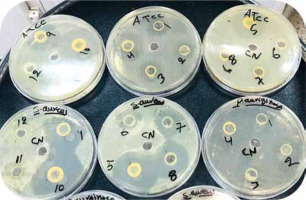

Fig. 1

Antibacterial activity of ethanol, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane extracts on different types of bacteria

Overall, the antibacterial values of tested AHA extracts against pathogenic bacterial isolates showed significant antibacterial activity. Figure 1 shows the various inhibition zones recorded on the plate. In general, different inhibition zones were recorded; however, the antibacterial activity of different fractions of AHA extracts were also tested by disc diffusion method against same 5 bacterial isolates. Based on the results shown in Table 1, these extracts exhibited antibacterial activities against most bacterial isolates.

Cytotoxicity of the plant extracts against MCF-7 and human foreskin fibroblasts cell lines

To assess the effect of ethanol extract against a human breast carcinoma cell line (MCF-7) in comparison to the HFF cell line, cytotoxic effects were assessed by MTT assay with concentrations of 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 µg/ml ethanol extract of AHA at 48 hours.

As depicted in Table 2, it is evident that the extract exhibited potential anticancer activity in a dose-dependent manner following a 48-h treatment; the results are expressed as % inhibition. Table 2 illustrates the results of cytotoxic effects (IC50) of different extracts on MCF-7 and HFF cell lines. It shows notable variations among the examined extracts, with the ethanol fraction showing IC50 546.75 ±16.00 at 31.5 µg/ml of extract concentration, compared with the HFF cell line.

Table 2

Cytotoxic effects of ethanoic extracts on MCF-7 and normal cell line (human foreskin fibroblasts)

Discussion

Recently, the study of the effects of combined treatments has increased because it has proven to be an alternative therapeutic outcome [31].

Medicinal plants are a useful strategy in treatment, with proven therapeutic effects in many areas, including antimicrobial and anticancer effects. The increase in the incidence of various types of cancer creates a need for new anticancer drugs that are toxic to cancer cells [32].

The reports from the World Health Organisation highlighting the growing prevalence of ARB have intensified the exploration of plant extracts with antibacterial properties for therapeutic purposes [33]. As a member of the Asteraceae family, Artemisia is among several genera known for its richness in secondary metabolites and essential oils, which possess valuable therapeutic applications. In this aspect, AHA extracts have shown a broad antibacterial action [34, 35].

The presence of active entities that elicit a primary biological response in the plant was detected using phytochemical analysis in both qualitative and quantitative terms. The presence of various bioactive secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, tannins, glycosides, saponins, phenolics, and flavonoids, but not Tri-Tribounds, was discovered during the preliminary phytochemical screening of AHA plant [36].

Noticeably, the increase of microbial resistance to antibiotics created several difficulties [37]. The severity of multidrug resistance is aggravated by the fact that there are no new antibiotics being discovered. The scientific and medical community should turn their efforts to find alternatives to antibiotics. One of the most common approaches is the search for the easiest and the safest to humans, which is medicinal plants. Plant extracts do not pose selective pressure issues and are unlikely cause resistance problems. One reason for choosing plants is that they are readily available [38]. The presence of alkaloids plays an important and effective role in antibacterial activity [39].

It may be the reason why these plants are used as anti-microbial presence Glycosides in AHA. So, it may be what made these plants make Staphylococcus aureus sensitive to other extracts is because glycosides. It consists of two parts: the first is sugar soluble in water and the second is non-sugar soluble in alcohol [40]. As for the phenols, their presence is due to the ability of these plants to kill and inhibit many microorganisms [41].

The results showed that methanol, being the most polar solvent, yielded a higher extraction quantity compared to n-hexane, which is less polar in nature. On the other hand, the results suggest that AHA contains substances with higher polarity than the others, which aligns with the findings of Benmeziane et al. [42], who noted that the extraction rate is influenced by the polarity of solvents.

In general, gram-positive bacterial strains were inhibited by all extracts while gram-negative bacteria were inhibited only by n-hexane and dichloromethane extracts. This result is consistent with other studies, which showed that n-hexane-based plant extracts had higher antibacterial activity compared to the extracts of other solvents [43]. Also, this result is consistent with those of the previous investigations of Mohammed et al. [25]. Ahameethunisa et al. [44] studied the antimicrobial activity of n-hexane extracts of Artemisia parviflora, which showed maximum activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumonia. This study demonstrated that Klebsiella pneumonia and Escherichia coli were resistant to AHA ethyl acetate extract. In a previous study, 6 organic Artemisia nilagirica solvents were tested against 15 phytopathogens and clinically significant standard reference bacterial strains. The results revealed that all the extracts had inhibitory activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, with the exceptions of Klebsiella pneumonia, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus aureus, which showed that these bacteria were resistant to Artemisia nilagiricais extracts. In research by Hussain et al. [43] (2022), it was shown that Artemisia rutifolia extracts in methanol, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane are rich in flavonoids and phenols, and that all the studied extracts effectively inhibited the development of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria across a broad spectrum.

Consequently, n-hexane was more effective against all the tested bacteria. This could be because the active chemicals are more soluble in hexane, which is in line with the observations of [20]. There have been several studies on the antibacterial and antioxidant properties of Artemisia species across the world. It is assumed that these plants produce important secondary metabolites that have therapeutic benefits against illness [45, 46]. Hexane extract is a very effective inhibitor for clinical pathogenic bacteria, as shown by the results of the zone of inhibition and MIC investigations [44].

The continuous search for new natural anticancer compounds within medicine plants and traditional foods is a promising strategy for discovering a new anticancer agent that is safe and capable of overcoming the multidrug resistance to conventional chemotherapy. Accordingly, the present research assessed the cytotoxic effects of AHA extracts against barest carcinoma cell lines (MCF-7).

Conclusions

Ethanol extract exhibited the most potent effects against pathogenic bacteria and MCF-7. Future research efforts should emphasise the isolation of particular chemical constituents from AHA and give priority to assessing their cytotoxic effects on mammalian cells. If certain elements prove to be safe, it would be intriguing to explore their potential therapeutic roles in addressing specific diseases, potentially combining traditional remedies with pharmaceutical treatments.