Introduction

Olfaction – its role and mechanism

The human olfaction apparatus is located in the upper part of the nasal cavity – the fornix. Adult human olfactory epithelium consists of 5 million receptor cells on 5 cm2 [1]. Air breathed in is firstly heated, secondly some of it does not get into the respiratory tract, but it stays in the olfactory area making whirl currents [2]. Epithelium contains bipolar cells and supporting cells and basal cells. Bipolar cells work as receptors and they are the first neuron in the olfactory tract. Every bipolar cell has between 8 and 20 cilia, which are directed towards the nasal cavity and immersed in mucus. This is the only place in a human body where sense cells have direct contact with the external environment. In the watery layer of mucus fragrance hydrophobic molecules dissolve, which increases their concentration. Supporting exocrine cells contain, beside mucopolysaccharides, lipids and phosphate protein binding fragrant substances (they become accessible to the receptor located on cilia) [2]. A neural-sensual olfactory cell is a neural cell with two appendages [3, 4]. One of the appendages ends with a sac covered with olfactory tentacles located between basal cells over the surface of epithelium. The second appendage transmits impulses from the cell body – working as an axon. Neural-sensual cells are neurons with a double role: they are chemoreceptors and impulse transmitting cells [3, 4].

Olfaction was appreciated especially after a Noble Prize in physiology and medicine was awarded to Richard Axel and Linda Buck for pioneering research in identification and memorizing fragrances [3]. Olfaction plays a significant role in a human’s life. Immediately after birth olfaction allows a neonate to identify the mother and takes part in initiation of suction [2]. Olfaction is mainly associated with fragrance detection, estimating fragrance intensity, identifying fragrance. Additionally it allows fragrances to be distinguished and fragrant impressions to be memorized, also imparting an appropriate emotional tinge [2, 5]. In daily life olfaction warns against dangerous substances nearby, the location of danger. It has a significant role in taste perception, and influences saliva and gastric acid production [6]. We should not minimize olfaction’s role in sexual life as well. Many people feel attracted by another person’s smell, or it may work the opposite way.

Olfaction is a significant sense of a human. Its loss or damage is painful and may negatively affect daily life, the more so that the smell functions include [3, 6]:

Warning against dangerous substances nearby, that put life and health in danger (smoke, poisonous gas), locating source of danger or unpleasant smell.

Selection of the right food (quantity and freshness) and keeping appetite at a safe level.

Participation in saliva and gastric acid production according to pleasant fragrances.

Important role in taste impression perception.

Creating full psychological comfort.

Influencing standard of life by sensing and evaluation of fragrances around in the natural environment.

Source of esthetic impressions, emotional and sexual behaviors.

Self-inspection in terms of hygienic state (smell of excrements and perspiration, etc.).

Important social information identification (identifying mother, child, suction).

Significant role in doing certain jobs (sommelier, chefs, pharmacists, firefighters, laboratory workers) [3].

Olfaction after total laryngectomy

In the last few years, a decreasing tendency has been observed in the quality of life area due to laryngeal cancer [7]. It is important to emphasize this, even more so after the continuously recorded increase in cases in the 80s and 90s of the last age [8]. In the example of Poland according to the latest National Cancer Registry, laryngeal cancer in 2015 was diagnosed in 2,171 men and 355 women [9]. This is a great achievement of early medical diagnosis and treatment [8]. This means that the number of people saved and the number of people with disabilities who are disabled are increasing. These people, as a result of treatment, will need help in, among other things, speech learning and olfactory therapy.

The role of olfaction is sometimes underappreciated, and problems with olfaction tend to be ignored. Healthy olfaction is rarely noticed [3]. Olfaction disorder though may be the first symptom of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson or Alzheimer, at times the only symptom of tumors in the frontal region [2]. The most common disorders are hyposmia – honed olfaction, parosmia, cacosmia – sensing abnormal fragrance, hyposmia – disability, weakening olfaction, and anosmia – loss of olfaction [6].

After total laryngectomy respiratory tract changes cause disability of nasal reflexes, including olfaction. Air flow through the nose in permanently moved to the tracheostoma, restricting contact between fragrant molecules and the nasal cavity, which may affect olfactory and taste perception [10]. Disorder or loss of olfaction after larynx resection causes a lower life standard and makes daily life more difficult [11].

According to comparative research in a group of patients after total laryngectomy (n = 25) and a group after treatment (n = 25) more patients with hyposmia were noted (88%, p < 0.001). Patients after treatment were weaker at detecting warnings and food fragrance [10].

There was also research on demonstrating whether total laryngectomy damages the olfactory epithelium. A group of people after treatment was gathered (n = 10) and one with people with a larynx. Both had olfactory tests, and a histological test was carried out afterwards. The test result showed a significant reduction in fragrance perception for people after laryngectomy. The histological test on the mucous membrane did not show any significant differences between people after and without laryngectomy. It was observed that patients with the larynx removed more frequently had inflammation of the olfactory epithelium [12].

In 2002 Frans Hilgers with his partners from the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam published an article paper which was a turning point in the attitude to complex rehabilitation after total laryngectomy. It was emphasized that rehabilitation should include respiratory system training as well as olfaction and taste. In 2010 it was also mentioned after an experiment in a group of patients after larynx removal that olfaction therapy should be included in complex rehabilitation [13].

It is proved that arousing olfaction after larynx removal is possible in research from 2008 [14]. 80 people after total laryngectomy were tested. The aim of the research was to estimate olfactory apparatus efficiency and analyze the process and results of rehabilitation during postoperative care. A survey, laryngological test and rehabilitation directed to force airflow in the nasal cavity were conducted. The exercise was carried out in therapeutic groups for 15 days of specialist rehabilitation sessions for patients after laryngectomy. There were conducted 1 hour classes with speech therapists for the whole group and also individual sessions with psychologists. Olfaction rehabilitation was conducted every day during group classes. Patients were also encouraged to do individual exercises according to a given instruction. Olfactory exercises took 15 min daily on average. Rehabilitation was carried out by qualified speech therapists and physiotherapists. The exercise involved causing airflow in the nasal cavity, which enabled fragrant molecules to get to the olfactory area. The following exercises were conducted:

Chewing with mouth closed.

Yawning with mouth closed.

With ala of nose squeezed, breathing in the air by movement of the soft palate through the nose and then releasing.

The exercise was done for both left and right sides. The research showed that 72 patients (90% of those tested) experienced damage or lack of olfaction after laryngectomy. After rehabilitation 35 patients (43.8%) experienced improvement of olfaction. No impact of age, gender or way of voice rehabilitation or chemotherapy on the results was noted. Negative factors for the rehabilitation were radiotherapy and time period after the operation [14].

Similar results were presented in 2010 [15]. The research was conducted in a group on 39 men and two women after larynx removal, which aimed to analyze olfaction function and evaluation of results of rehabilitation with induced airflow in the nose. All the people were rehabilitated with the induced airflow in nose technique, then their olfaction was tested again and the results were compared to the previous ones. Out of 41 patients taking part in the research 9 had olfactory perception before rehabilitation according to the first olfaction test. Using airflow turnup in the nose resulted in recovery or improvement of olfaction for 90.24% of patients. The research showed that using the technique of induced airflow in the nose enables significant recovery or improvement of olfaction and taste after total laryngectomy [15].

Unfortunately olfaction therapy is rarely included in rehabilitation after total laryngectomy [12].

Material and methods

The subject of the study was the effectiveness of using olfactory maneuvers in people after laryngectomy.

Purpose of the research

The aim of the study was to show the subjective effectiveness of use of olfactory maneuvers by people after laryngectomy.

Material

During the rehabilitation session, which aimed to teach and improve esophageal speech for people after larynx removal, fragrance smelling exercise therapy was included. The session took place in June 2018 by the seaside, and lasted two weeks; participants were members of the Polish Society of People after Laryngectomy. There were 2 people. The rehabilitation included the following daily activities:

From 7:00 till 8:00 group physical classes on the beach using Nordic walking sticks.

Between 9:00 and 15:00 each participant had two individual physiotherapeutic treatments (mostly whirl bath or inhalation.

Between 9:00 and 14:00 speech therapy in pairs, 30 minutes each class.

From 14:00 to 14:30 group speech therapy classes for volunteers.

An olfaction test was taken by 19 people, at the age of 65 on average (between 47 and 78). The average period of time after larynx removal was 6.4 years (between 1 and 28). There were 6 women at the average age of 63 (between 47 and 70) and 13 men at the average age of 66 (between 52 and 78). Every participant had follow-up radiotherapy. Everyone took part in natural strategy logopedic treatment based on learning and improving esophageal speech: 4 people used pseudo whisper, 5 people beginner esophageal speech, 5 good esophageal speech and 5 very good. Only one person had not smoked cigarettes before larynx removal.

A test on olfaction was conducted on the 7th day of rehabilitation. Participants were divided into 2–3 person groups. Every participant signed an agreement to take part in the test and sessions. Every person was interested in the exercise, and was happy about doing the exercise, because they admitted that loss of olfaction after total laryngectomy is very painful. Instruction was presented.

There were 10 products with intensive fragrance used in the research: cold strong mint tea, orange skin, strawberry jelly dessert, paprikash, vinegar, sour cabbage, horseradish, mustard, coffee, and sour cucumber. Every product was paced in a separate brown, non-transparent mug. The meeting took place as follows:

Mugs were placed on the table and products were listed.

The leading person covered the participant’s eyes before product presentation and let them smell, putting the mugs with fragrance close to the nose and lips, allowing them to “breath in” and “smell” in any individual way.

After presenting the fragrance the participant’s eyes were uncovered and the answer was written and read by the participant or their representative in case of lack of ability to speak.

Next, after the presentation, the therapist demonstrated an exercise aiming to improve olfaction. Every participant learned it by repeating for about 15 minutes.

Fragrance presentation was repeated. This time every participant did the recommended “maneuvers” as long as they nodded that they knew the answer.

Fragrances at the second time were presented in a different order. Participants did not consult the answers.

The exercise called “airflow-inducing maneuvers” involved doing the following actions:

Open mouth wide, gathering as much air inside as possible, close mouth.

Cover the right nostril and try to breath in as much air as possible with the mouth closed through the left nostril.

Cover the left nostril and try to breath in as much air as possible with the mouth closed through the right nostril.

Take air into the mouth again, close it and move the jaws round, with suction moves in order to move the air to the nasal cavity.

The procedure was repeated many times during 15 minutes.

Results

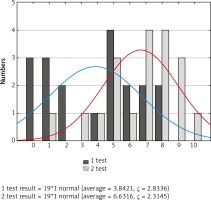

19 people completed the research. The were two surveys conducted – immediately before learning maneuvers and after using them. At the beginning it was verified how many people recognized fragrances without using any assisting moves. Next it was checked how many fragrances were recognized by each participant after the second exposure using airflow-inducing maneuvers (Fig. 1). Analysis of the results showed that there were: 3 people who did not sense any fragrance, 3 people sensing 1 fragrance, 2 people sensing two fragrances, 1 person sensing 4 fragrances, 4 people sensing 5 fragrances and 2 people sensing 6, 7 and 8 fragrances. After the second test there was no person who did not recognize any fragrance and there was no person whose olfaction deteriorated.

Results of using airflow-inducing maneuvers are as follows:

2 participants did not recognize any more fragrances than before,

6 participants recognized one more fragrance,

3 participants recognized 2 more fragrances,

1 participant recognized 3 more fragrances,

3 participants recognized 4 more fragrances,

2 participants recognized 6 more fragrances,

2 participants recognized 7 more fragrances.

Before using airflow-inducing maneuvers the average result of fragrance recognition after the first test was 3.84, after the second test 6.63. The average effect is 2.78 with standard deviation 2.32 (Table 1).

Table 1

Descriptive statistics for results of olfaction test

| Result | n | Average | Min | Max | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After 1 test | 19 | 3.842105 | 0.000000 | 8.00000 | 2.833591 |

| After 2 test | 19 | 6.631579 | 1.000000 | 10.00000 | 2.314460 |

| Effect | 19 | 2.789474 | 0.000000 | 7.00000 | 2.323287 |

It was decided to measure the association between therapy effects (dependent variable) and age and period of time after larynx removal (independent variable).

After using Student’s t-test it was found that there was an association between olfaction therapy effects and participants’ age. The result is statistically significant: t = 33.9 with p < 0.05. No association between number of years after the operation and effects of maneuvers was discovered (Table 2).

Table 2

Student’s t-test for age and number of years after total laryngectomy vs. therapy effects

Discussion

Olfaction training was included in rehabilitation for the first time in 2002 by the team of Hilgers from the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam. Based on conducted research it was proved that 30-minute olfaction exercise for people after larynx removal may arouse sensing fragrances.

A team of researchers from the Head and Neck Cancer Surgery Clinic of the Medical University of Lodz led by Zimmer-Nowicka based on Hilgers and his team’s achievements conducted such research in a group of people after total laryngectomy, where they found that using airflow-inducing maneuvers, effects were recognizable immediately after learning them. Test results presented in the article confirm the achievements of researchers from Łódź, because the presented group of 19 people after total laryngectomy got their results immediately after short olfaction training. Every participant stated that they had not had any olfaction training until that time, which encouraged interest and engagement during the classes. According to the conducted research using airflow-inducing maneuvers patients after total laryngectomy can sense fragrances significantly better.

Unfortunately it appears that not many people after larynx loss include use of airflow-inducing maneuvers in their daily life. This may come from acceptance of disability or lack of olfaction or lack of instruction on how to improve olfaction.

Conclusions

Olfaction rehabilitation for patients after laryngectomy should be an obligatory part of complex rehabilitation. Based on the example of the Netherlands Cancer Institute, the therapy in conducted by speech therapists. It has been described in Poland since 2012 in publications on the new specialization oncologopedics, specialization working on speech disorder, communication primary actions with an oncological background [16]. Based on the conducted research it is recommended to include speech therapists in specialist teams treating patients with cancer, because they are in the closest contact with patients after total laryngectomy later because of the speech learning process.