Summary

Cardiac involvement in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a major contributor to adverse outcomes, yet its detection at a subclinical stage remains challenging. This study demonstrated that patients with AAV exhibit impaired strain in both ventricles and increased left ventricular dyssynchrony as assessed by speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE). These findings highlight the value of STE in the early identification of subclinical myocardial dysfunction. Routine implementation of STE may improve risk stratification and support earlier clinical interventions in AAV management.

Introduction

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) are a group of autoimmune diseases that result in systemic inflammation and affect small blood vessels [1]. The three main clinical subtypes of AAV are granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) [2]. The confirmation of a diagnosis is achieved through the presence of either MPO or PR3 antibodies. While renal and pulmonary systems are commonly affected, cardiac manifestations can progress without noticeable symptoms. However, recent studies have indicated that patients with AAV who have cardiac involvement experience significantly higher rates of mortality and morbidity [3].

AAV is associated with a wide range of cardiac issues, including coronary artery disease, pericarditis, myocarditis, endocarditis and myocardial infarction [4–6]. However, these cardiac manifestations may occur at a subclinical level, making them difficult to detect with conventional echocardiography. As a result, advanced imaging techniques have become increasingly important for the early and accurate detection of myocardial involvement. Speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) may be a reliable tool for detecting subclinical myocardial dysfunction [7]. Previous studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of silent cardiac involvement in AAV patients [8–10]. Despite these findings, no study to date has systematically evaluated, in detail, both left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) strain parameters using STE in patients with AAV. Furthermore, although LV dyssynchrony assessed by LV peak systolic dispersion (PSD) measured via STE is an emerging marker of electrical and contractile heterogeneity [11], its role in AAV-related cardiac involvement has not been thoroughly investigated.

Aim

The aim of this study is to evaluate LV and RV function, as well as LV dyssynchrony, using STE in patients diagnosed with AAV, with a particular focus on detecting subclinical myocardial dysfunction. We hypothesized that patients with AAV might have impaired ventricular strain parameters and increased LV dyssynchrony as assessed by STE.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study included 39 consecutive patients with a confirmed diagnosis of AAV without cardiac symptoms, and 44 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. The patient group was selected from ambulatory, clinically stable patients who had been under regular follow-up at the nephrology and/or rheumatology clinics for at least 1 year. Exclusion criteria were presence of coronary artery disease (patients with angina, documented ischemia with exercise stress testing or myocardial perfusion scan, coronary stenosis documented by coronary angiography, or previous coronary revascularization history), bundle branch block (QRS > 120 ms), congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, essential hypertension, diabetes mellitus, active infection, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of malignancy and poor echocardiographic image quality. The control group was screened with a clinical examination to exclude AAV and similar systemic autoimmune diseases.

The baseline characteristics, detailed medical history, comorbidities and cardiac symptoms of all participants were thoroughly assessed. Body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), and a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) were recorded prior to echocardiographic examination. Blood samples were collected after at least 8 h of fasting, and routine biochemical tests including lipid profile, creatinine, inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), as well as a complete blood count, were analyzed using automated standard laboratory methods. The antibodies of the patients were assessed before echocardiographic examination and patients were categorized according to antibody subtypes (MPO or PR3).

Echocardiographic measurements

All participants underwent echocardiographic assessment using a GE Vivid E95 (Horten, Norway) device. Measurements were performed by an experienced cardiologist using the same device. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed by a single experienced echocardiography specialist who was blinded to the participants’ AAV diagnosis.

Participants were assessed in the left lateral decubitus position. Conventional echocardiographic measurements included standard LV dimensions, ejection fraction (EF), diastolic function parameters (E/A ratio, eʹ velocity, E/eʹ), and RV function indices such as tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), RV systolic velocity (RVsʹ) and tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV).

STE was performed in all patients and controls in addition to conventional echocardiographic assessment, and analyses were conducted using the dedicated software of the ultrasound system. Global longitudinal strain (GLS) was assessed using well-standardized automated function imaging (AFI) software (GE Healthcare). Measurements for STE analysis were recorded using ECG monitoring of three consecutive beats in sinus rhythm. LV GLS analysis was conducted using images obtained from apical four-chamber (A4C), two-chamber (A2C), and three-chamber (A3C) views. Figure 1 illustrates the strain analysis derived from the A4C view. The software automatically tracked the endocardial contour for analysis, with manual adjustments made for segments with poor tracking quality. Patients with inadequate tracking in two or more segments were excluded from the study. The GLS values obtained from A4C, A3C, and A2C images were recorded and a 17-segment bull’s-eye plot was generated. LV PSD was assessed using the standard deviation of time to peak longitudinal strain in 17 myocardial segments, automatically calculated by the STE software (Figure 2). RV GLS and RV free wall strain (RV FWS) were also measured from RV dedicated A4C views with STE.

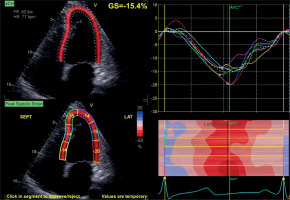

Figure 1

Apical four-chamber view showing LV longitudinal strain analysis using Automated Function Imaging (AFI) by speckle-tracking echocardiography. Global longitudinal strain (GLS) is –15.4%, with segmental strain curves and a color-coded strain map displayed

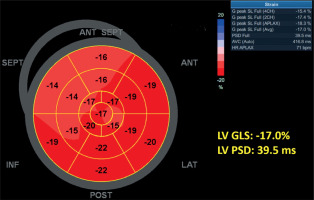

Figure 2

Bull’s-eye plot of left ventricular longitudinal strain derived from apical views using speckle-tracking echocardiography. The global longitudinal strain (LV GLS) is –17.0%, and peak systolic dispersion (LV PSD) is 39.5 ms, automatically calculated by the software

To enhance measurement reliability, optimal image quality was ensured, the frame rate was adjusted between 50 and 80 frames per second (fps) for conventional echocardiographic measures, and all images were meticulously reviewed to exclude low-quality recordings from the analysis. The frame rate was maintained between 30 and 40 fps for optimal speckle tracking.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approval was obtained from the relevant local ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 27.0). Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Independent t-tests were used for normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test and expressed as counts and percentages n (%). Normally distributed continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas non-normally distributed data were presented as median (interquartile range). The correlation between LV GLS, LV PSD and other continuous clinical parameters was assessed by Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis, depending on the data distribution. Linear regression analysis was performed to identify independent associations with LV GLS and LV PSD. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

The study included 39 consecutive patients with AAV (mean age: 52.9 ±12.8 years, 19 male sex) and 44 healthy controls (mean age: 50.2 ±8.7 years, 28 male sex). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients and controls are shown in Table I. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of age, sex, BMI, and systolic and diastolic BP.

Table I

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between AAV patients and controls

[i] Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as number (%). AAV – ANCA-associated vasculitis, ANCA – anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, BMI – body mass index, BP – blood pressure, CRP – C-reactive protein, ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate, HDL-C – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, MPO – myeloperoxidase, NA – not applicable, PR3 – proteinase 3, WBC – white blood cells.

The conventional echocardiographic parameters of the AAV patients and controls are presented in Table II. Although LV EF was similar between AAV patients and controls, AAV patients had significantly lower early diastolic mitral inflow velocity, early diastolic lateral mitral annular velocity, and a significantly higher E/eʹ ratio and TRV.

Table II

Conventional echocardiographic parameters of the AAV patients and controls

[i] Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. AAV – anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated vasculitis, A – late diastolic mitral inflow velocity, A – lat – lateral mitral annular late diastolic velocity, DT – deceleration time, E – early diastolic mitral inflow velocity, E – lat – lateral mitral annular early diastolic velocity, E/e’ lat – ratio of early mitral inflow, IVS – interventricular septum thickness, LA – left atrium, LVEDD – left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, LVESD – left ventricular end-systolic diameter, PW – posterior wall thickness, S – lat – Lateral mitral annular systolic velocity to lateral annular velocity, RVs – – right ventricular systolic velocity, TAPSE – tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, TRV – tricuspid regurgitation velocity.

The 2D STE parameters of AAV patients and healthy controls are summarized in Table III. The LV GLS was also significantly reduced in AAV patients (–16.6 ±2.2% vs. –19.6 ±2.0%, p < 0.001). LV dyssynchrony measured by LV PSD was significantly higher in AAV patients than controls (54.9 ±14.8 ms vs. 43.9 ±11.8 ms, p < 0.001). RV GLS and RV FWS were significantly lower in AAV patients compared to controls (RV GLS: –19.2 ±2.7% vs. –20.6 ±2.8%, p = 0.024; RV FWS: –21.6 ±3.7% vs. –23.9 ±3.5%, p = 0.004). Additionally, there were no statistically significant differences between the MPO and PR3 subtypes in LV GLS (MPO: –16.97 ±2.41% vs. PR3: –16.27 ±1.90; p = 0.325), LV PSD (MPO: 55.70 ±15.91 ms vs. PR3: 53.98 ±13.93 ms; p = 0.724), or RV GLS (MPO: –19.77 ±2.55 vs. PR3: –18.71 ±2.89; p = 0.233) values.

Table III

Speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) measures of AAV patients and controls

[i] Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. AAV – anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis, FWS – free-wall strain, GLS – global longitudinal strain, LV – left ventricle, RV – right ventricle, PSD – peak systolic dispersion, 4Ch – 4 chamber view, 3Ch – 3 chamber view, 2Ch – 2 chamber view.

LV GLS of the AAV patients showed a weak but significant negative correlation with CRP (r = –0.334, p = 0.038), but did not show significant correlations with most clinical variables, including age, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, creatinine, and WBC count (Table IV). LV PSD was not significantly correlated with any of the evaluated clinical variables.

Table IV

Correlation analysis between LV GLS, LV PSD, and other clinical variables in patients with AAV

[i] Data are presented as Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and p values. AAV – anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis, BMI – body mass index, BP – blood pressure, CRP – C-reactive protein, ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate, LV GLS – left ventricular global longitudinal strain, LV PSD – left ventricular peak systolic dispersion, WBC – white blood cells.

Multivariable linear regression analysis demonstrated that the presence of AAV was independently associated with both LV GLS (β = –2.930, 95% CI [–3.987 – –1.873], p < 0.001) and LV PSD (β = 7.819, 95% CI [1.367–14.270], p = 0.018). Additionally, older age was independently associated with LV PSD (β = 0.284, 95% CI [0.012–0.557], p = 0.041), whereas no significant associations were observed for sex or serum creatinine levels with either LV GLS or LV PSD in the multivariable model (Table V).

Table V

Multivariable linear regression analysis for LV GLS and LV PSD

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively assessed cardiac function and LV dyssynchrony using two-dimensional STE in patients with AAV. Our findings showed a significant reduction in LV GLS among AAV patients, indicating the presence of subclinical LV dysfunction despite a normal EF. Additionally, elevated LV PSD values, which reflect LV dyssynchrony, suggest notable intraventricular mechanical heterogeneity. RV GLS values were also significantly lower compared to the control group, implying that AAV may also impact the RV. In addition, several indices of LV diastolic function were found to be impaired, suggesting that diastolic dysfunction may also be present in patients with AAV. Furthermore, we found that the presence of AAV was independently associated with impaired LV GLS and increased LV PSD.

The pathogenesis of AAV involves a complex interaction of multiple mechanisms, including necrotizing vasculitis targeting small vessels, endothelial injury, immune complex deposition, and the impact of inflammatory mediators [12]. This cascade can lead to myocardial fibrosis, microvascular ischemia, and ventricular remodeling, ultimately resulting in subclinical cardiac dysfunction. Miszalski-Jamka et al. identified LV systolic abnormalities in 73% of patients with GPA using STE, despite normal EF [13]. Izgi et al. demonstrated significantly reduced LV GLS and RV GLS in patients with AAV [14]. In our study, the decreased LV GLS and RV GLS indicates subtle myocardial impairment. Pugnet et al. reported silent cardiac involvement in 61% of GPA patients, as evidenced by late gadolinium enhancement and segmental wall motion abnormalities on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [10]. Sartorelli et al. also demonstrated a high prevalence of cardiomyopathy in EGPA, attributed to eosinophilic myocardial infiltration [15]. Ahn et al. reported elevated TRV in AAV patients, indicative of potential pulmonary hypertension (PH) [16]. Similarly, Baqir et al. reported a PH prevalence of 14.8% in patients with AAV, which was most commonly associated with left heart or chronic lung disease [17]. However, in our study, the TRV values, although slightly higher compared to controls, were still within normal limits. This mild elevation suggests that RV dysfunction observed in our cohort is likely due to direct myocardial involvement related to AAV itself, rather than significant secondary PH.

LV PSD, derived from STE, quantifies the variability in timing of peak myocardial contraction across segments and reflects mechanical dyssynchrony [18]. Although no prior study has systematically evaluated LV dyssynchrony (LV PSD) in AAV, its clinical significance has been demonstrated in related inflammatory conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Luo et al. found that drug-naive patients with new-onset SLE exhibited increased LV PSD, indicating subclinical LV dyssynchrony [19]. Similarly, mechanical dyssynchrony has been investigated in patients with systemic sclerosis, further supporting the concept that dispersion-based deformation parameters are sensitive to myocardial involvement in rheumatologic diseases [20]. Consistently, our study demonstrated significantly increased LV PSD in AAV patients despite preserved EF, implying the presence of subtle mechanical incoordination that is not detectable by conventional echocardiography. Although LV PSD was higher in AAV patients, the increase was modest, and values largely remained within a range of uncertain clinical significance. This should be interpreted cautiously, as there is no widely accepted reference value for PSD [21].

Our findings may be attributed to subclinical inflammation or fibrosis of the myocardium, which could disrupt the pathways for conduction within the ventricles and lead to mechanical dispersion. Furthermore, localized myocardial damage, as opposed to widespread damage, may cause delays in regional contraction and result in LV dyssynchrony, even when there are no visible abnormalities in the conduction system. Moreover, in AAV patients, elevated LV PSD correlated with higher disease activity and CRP, suggesting that LV dyssynchrony assessed by STE may serve as an early marker of myocardial electrical and mechanical heterogeneity with potential prognostic implications in AAV.

Diastolic dysfunction may also occur in patients with AAV. A previous study demonstrated a significantly higher E/eʹ ratio, as well as increased A and a lower eʹ velocity, in patients with AAV compared to controls, indicating impaired LV relaxation and elevated filling pressures near the time of diagnosis [16]. Consistent with these findings, our study also revealed significant diastolic abnormalities in AAV patients, including reduced early diastolic mitral inflow velocity (E), increased A-wave velocity, prolonged deceleration time, and reduced lateral eʹ velocities. Although the E/eʹ ratio was slightly increased in our AAV patients, it remained within normal limits, suggesting only mild alterations in LV filling pressures without clinically significant diastolic dysfunction.

Inflammation in AAV has a complex impact on the cardiovascular system, with CRP serving as a key mediator in this pathological process. In our study, a weak but significant negative correlation was observed between CRP levels and LV GLS, suggesting that inflammation may impair the LV myocardium at a subclinical level, even when EF is normal. Booth et al. found a significant relationship between CRP levels and arterial stiffness in patients with active AAV, indicating that CRP may act not only as a marker of inflammation but also as an independent contributor to increased vascular stiffness [22]. Similarly, Wu et al. demonstrated that monomeric CRP (mCRP) was more strongly associated with cardiovascular complications in AAV than conventional CRP [23]. Moreover, Da Silva Domingues et al. reported significantly higher CRP levels in PR3-ANCA positive patients compared to MPO-ANCA positive individuals, suggesting a greater inflammatory burden in the PR3-positive subgroup [24]. A previous study also linked PR3-ANCA positivity to more frequent relapses and higher long-term mortality, underscoring the need for closer cardiac monitoring in this subgroup [3]. However, in our study, no significant differences were observed in LV GLS or LV PSD values between MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA positive patients. This finding may reflect the subclinical nature of myocardial involvement at the time of evaluation or the potential effect of immunosuppressive therapy in attenuating differences between ANCA subtypes.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate LV dyssynchrony in patients with AAV, highlighting its novel contribution to the field. Furthermore, the presence of significant impairments in both LV GLS and RV GLS suggests that subclinical involvement may affect both ventricles simultaneously. The lack of significant differences in strain parameters between ANCA subtypes (MPO vs. PR3) also implies that subclinical cardiac dysfunction may develop independently of ANCA phenotype, thereby offering a new perspective to the existing literature. In contrast to previous studies focusing on individual AAV subtypes such as GPA or EGPA, our inclusion of all AAV phenotypes enhances the generalizability of the findings. This comprehensive approach reflects real-world clinical practice and supports the notion that early cardiac involvement may be a common feature across the AAV spectrum, regardless of subtype. While STE may provide valuable insights into subclinical cardiac involvement, routine screening of all AAV patients is not yet recommended. Further studies with larger cohorts and long-term follow-up are necessary to identify the high-risk subgroup.

This study has several limitations. The relatively small sample size may have limited the statistical power, particularly in comparisons between ANCA subtypes. Additionally, CMR, the gold standard for assessing myocardial fibrosis and structural changes, was not performed, limiting the evaluation of such alterations. We excluded patients with known coronary artery disease, as it might affect strain measures. However, we did not perform specific tests for unknown/subclinical coronary artery disease. Finally, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study and lack of prospective clinical follow-up, the prognostic significance of reduced GLS and increased LV PSD regarding important clinical outcomes such as the development of arrhythmias, incidence of hospitalization due to cardiac events, and overall cardiovascular mortality could not be established.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that patients with AAV exhibit reduced GLS and increased LV PSD, suggesting myocardial involvement and LV dyssynchrony despite normal EF. These findings emphasize the presence of subclinical myocardial dysfunction, which can be assessed with STE. However, the increase in PSD was modest, and its clinical relevance remains uncertain in the absence of universally accepted reference values. Our results also revealed RV involvement, indicating that cardiac dysfunction in AAV is not limited to the LV. Incorporating STE into routine clinical practice for initial screening and periodic follow-up of AAV patients may facilitate the early detection of subclinical cardiac involvement and improve risk stratification, allowing timely intervention even in asymptomatic individuals. Prospective studies with rhythm monitoring and long-term follow-up are needed to clarify the prognostic significance of dyssynchrony in this population.