Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) infection remains one of the most prevalent chronic liver disease worldwide. It is estimated to be the major cause of liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver transplantation [1]. CHC treatment has improved with the introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). A sustained virological response (SVR) can be achieved at high rates for CHC patients receiving DAAs, regardless of genotype and patients’ clinical characteristics [2]. SVR has been associated with lower risk of liver decompensation, the need for liver transplantation, liver-related events, and overall mortality. However, even small subsets of patients achieving SVR still have a risk of developing HCC. Patients with SVR are at risk of developing HCC, with a 3-year cumulative incidence of 4.9% [2]. An effort to identify factors contributing to the heightened risk of developing de novo HCC after SVR is urgently needed.

Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is rising in prevalence. It is associated with increased risk of HCC. Metabolic dysfunctions, such as diabetes mellitus and obesity, are reported to be risk factors of HCC after hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication. A new fatty liver definition, MAFLD, has been proposed by an expert panel, characterized by inclusion criteria of metabolic abnormalities. The term MAFLD can be used regardless of the status of viral infection. MAFLD is strongly associated with liver-related outcomes and provides better prognostic value than the previous term, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [3, 4].

We aimed to summarize the effect of MAFLD on HCC development in CHC patients, even after achieving SVR.

Material and methods

Study selection

Our meta-analysis adhered to PRISMA guidelines. Three independent investigators conducted a literature search in PubMed and Google Scholar from inception to July 7, 2024, restricting the search to studies involving humans and articles published in English. We used Medical Subject Headings and free-text terms for the keywords, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Search strategy

Eligibility criteria

We included studies if they met the following criteria: 1) the study was a cohort study, 2) the study estimated the association between the presence of MAFLD or metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) or NAFLD and HCC risk in CHC patients who achieved a sustained virological response, 3) the study reported hazard ratios (HRs) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or presented raw data. When the study carried out analyses with adjustment for confounding factors, we chose the adjusted over unadjusted HR. The following literature was excluded: 1) short communication, correspondence, letter to the editor, conference abstracts, review, or case reports, 2) desirable data could not be retrieved, 3) full-text articles were not available 4) non-English articles.

Assessment of bias risk

The risk of bias of included studies was separately assessed by two investigators using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Studies with an NOS score < 7 were considered to have a high risk of bias, whereas those with a score ≥ 7 were considered to have a low risk of bias.

Data extraction

The same two investigators independently extracted the following data from each study using a prespecified form: author, year, study design, country, sample size, follow-up year, MAFLD/MASLD/NAFLD diagnosis criteria, outcome – HCC diagnosis criteria, and adjustment used. We contacted authors for additional data or clarification when needed.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the impact of liver steatosis on HCC development in CHC patients with SVR through pooled HRs with their corresponding 95% CIs. Data were pooled based on fixed-effects or random-effects assumptions. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. The Higgins’ I 2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity. If the value of I 2 was < 50%, a fixed-effect model was applied. Otherwise, a random effects model was used. We planned to assess publication bias through a funnel plot if included studies reached the minimum number of 10. An asymmetric plot would suggest publication bias. All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager version 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration).

Results

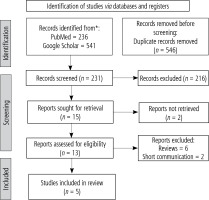

After deleting duplicates and reviewing titles and abstracts for eligibility, 231 of the 777 potential records identified by the search approach were excluded. Five studies were found to be eligible for qualitative and quantitative synthesis after additional full-text inspections for 13 articles (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the five studies are summarized in Table 2. The studies involved 7,034 patients, ranging from 924 to 2611 patients in each study, originating from 4 different countries. Studies were published between 2017 and 2024. The diagnosis criteria for steatosis/NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD and HCC and CHC treatment varied across studies, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Study characteristics

[i] AFP – a-fetoprotein, APASL – Asia Pacific Association Study of the Liver, BMI – body mass index, CHC – chronic hepatitis C, DAA – direct-acting antivirals, DM – diabetes mellitus, EASL – European Association Study of the Liver, HCC – hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV – hepatitis C virus, NA – not available, NAFLD – non-alcoholic associated fatty liver disease, MAFLD – metabolic associated fatty liver disease, MASLD – metabolic associated steatosis liver disease, MRI – magnetic resonance imaging, SVR – sustained virological response, US – ultrasonography

Quality of included studies

The study quality ranged from 6 to 8, as shown in Table 3. Two studies were found to have a high risk of bias, whereas three were found to have a low risk of bias.

Publication bias

We were not able to conduct publication bias assessment through a funnel plot as the number of studies included in the subgroup analysis did not reach 10.

Metabolic dysfunction and HCC risk after SVR

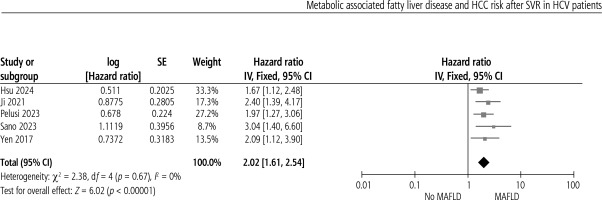

Metabolic dysfunction is associated with increased risk of HCC after SVR in CHC patients (HR = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.61-2.54, p < 0.00). No heterogeneity was present, as shown in Figure 2.

Discussion

Interpretation

The current research summarized the association between liver steatosis/NAFLD/MAFLD and risk of HCC after SVR in CHC patients from 5 observational studies. From our pooled results, metabolic dysfunction is associated with increased risk of HCC development in CHC patients with SVR. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the determined prevalence of NAFLD in CHC patients in each study varied greatly, from 5.9% to 57.6%, with 1 included study unavailable for analysis. The variation may be due to differences in diagnosis criteria used for NAFLD/MAFLD/metabolic dysfunction in each study. The HCC cumulative incidence rate was also found to vary, from 4.35% to 14.36%. Follow-up duration differences across study may influence the variation of cumulative incidence rate. Nonetheless, despite variation across studies, the pooled data showed a significant correlation between presence of metabolic dysfunction and increased risk of HCC in CHC patients after SVR.

Influence of viral proteins in HCV-mediated steatosis

The underlying mechanism has now been actively studied. CHC presents with not only intra-hepatic manifestations, but also extra-hepatic manifestations, such as lymphoma, autoimmune disease, vasculitis, and cardiometabolic diseases. Some of these signs are consistent with host metabolic dysfunction occurring concurrently with or in reaction to HCV infection.

HCV proteins, especially in genotype 3, directly disturb the host’s metabolism on four levels: a) By activating several transcription factors related to lipid metabolism, HCV promotes de novo lipidogenesis, which in turn aids the assembly of HCV lipid and viral particles [5-7]; b) HCV stimulates the production of lipotoxic ceramides, phospholipids, and sphingomyelins, all of which are crucial for viral replication and HCV assembly [8]; c) HCV prevents the oxidation of mitochondrial fatty acids [5, 9]; d) lipoviroparticle formation obstructs the very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion pathway, preventing VLDL from assembling and being exported [10]. Indirectly, HCV alters hepatic metabolism through peripheral insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperglycemia [11].

HCV-mediated steatosis: the role of host obesity and adipose tissue dysfunction

Obesity is described as increased energy uptake and/or decreased energy expenditure, resulting in adipose tissue (AT) dysfunction leading to metabolic syndrome [12]. Metabolic dysfunction occurs when adipose tissues exceeds its expandability limit [13]. However, obesity definition is not limited according to body mass index, as lean CHC patients can also develop AT dysfunction [14, 15]. Thus, it is imperative to find another marker apart from body mass index (BMI) to define metabolic dysfunction in this subgroup of patients. During the interferon era, obesity is closely related to SVR; thus, weight reduction plays a role in the management of patients [16]. However, SVR during DAA does not depend on BMI [17]. An interesting finding is that the subgroup of patients who achieved SVR during DAA gained weight along with an improvement in quality of life as well as improvement of intake after SVR [18]. This is why a weight gain might explain the blunted clinical response even after SVR. However, it is still debated, because DAA improves extrahepatic insulin sensitivity after SVR.

Precancerous niche in CHC

Effect of virus

HCV is an RNA virus whose existence is limited in the cytoplasm; hence it does not possess the ability to integrate with the host’s genome [19]. However, HCV protein promotes cell proliferation, mesenchymal epithelial transition as well as angiogenesis through modulation of the signaling cascade [20], thus reflecting metabolism dysregulation.

Lipotoxicity

Metabolism dysregulation in hepatic cells will result in an accumulation of toxic lipid; hence, lipotoxicity occurs, leading to cell dysfunction and injury. HCV core protein can increase the reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, directly through increased production of NOX1 and NOX4 and indirectly through mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress and an impaired antioxidant mechanism [21-24]. Lipotoxicity drives cell death and activates the chronic process of wound healing, thus promoting progression of CHC to HCC.

Immunosurveillance dysfunction

In eliminating HCV, the innate immune system and adaptive immune system are needed [25]. In the majority of patients, the immune system is unable to eradicate the virus, hence resulting in a chronic infection state. Immunosurveillance, the ability to identify and eliminate the virus, is impaired in HCV, even after undergoing DAA therapy [26]. CD8+ T cells are major immune cells responsible for eliminating HCV. However, in HCV-infected patients, CD8+ T cells experience progressive exhaustion, with features of impaired cytotoxic activity and anti-tumoral activity, hence predisposing to HCC [27-30]. CD4+ T cells are required to maintain the antivirus activity of CD8+ T cells, but their ability to do so is also impaired in HCV infection [31]. Natural killer (NK) cell levels in HCV-infected patients decrease even after a complete course of DAA therapy, hence contributing to the more impaired immunosurveillance function [32, 33].

Senescence

Oxidative stress can cause chronic injury, thus resulting in an increase of compensatory proliferation and further raising the risk of telomere shortening and senescence [34, 35]. Impaired immunosurveillance will be unable to eliminate senescent cells, hence leading to genomic instability, which further raises the possibility of cancer clone formation [36]. Senescence induces a precancerous environment through senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) formation, which in turn induces adjoining cells to become senescent. SASP is profoundly pro-inflammatory as it induces further telomere shortening [37, 38]. Senescence causes systemic and hepatic metabolic dysfunction, which later provokes worsening of steatosis, creating a vicious cycle [35]. Senescence is an attempt to limit the development of cancer clones, but it can also cause metabolic dysfunction and increase the risk of HCC in the long term.

Chronic inflammation and fibrosis

Fibrosis of the liver is the most important clinical entity in liver disease as it is the strongest predictor of overall mortality [39]. The presence of liver fibrosis creates a precancerous environment. Fibrosis formation is mediated by activation of liver stellate cells, which produce collagen as a response to injury. Activated myofibroblasts, a product of liver stellate cells which undergo differentiation, release cytokines such as transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which impair immunosurveillance and promote angiogenesis and tumoral invasion and proliferation [40].

The systemic metabolic profile has the ability to promote fibrosis and activation of myofibroblasts through metabolic reprogramming [41]. Myofibroblast activation can be disturbed by conditions related to metabolic disease: a) in hyperinsulinemia and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), myofibroblasts express insulin receptor and upregulate TGF-β and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), which increase fibrogenesis; b) myofibroblasts express functional leptin receptor and promote myofibroblast proliferation, collagen secretion, and apoptosis inhibition [42-44].

Implications for strategies: preventing HCC development and follow-up after SVR

Diet and exercise

Several studies have shown an inverse correlation between physical activity and risk of HCC, not specific to HCV-infected patients [44]. The Mediterranean diet has been shown to be protective against HCC, especially in the CHC subgroup, through reduced steatotic burden, slower progression of liver disease, limited consumption of foods with a refined carbohydrate content, and decreased metabolic pressure on cell proliferation caused by insulin signaling [45]. Dietary cholesterol is associated with an increased risk of disease progression in patients with CHC and advanced fibrosis [46].

Pharmacological management

Novel studies investigating the pharmacological interventions aimed at reducing the fibrotic progression of CHC to HCC are still new, with the introduction of statins, metformin and aspirin. Lipophilic statins lower the risk of CHC in HCC patients through modulating cholesterol synthesis. Studies have shown that statins also reduce the risk of fibrotic progression [47]. Metformin, despite its limited use in the type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) subgroup, has been shown to be useful in CHC and T2DM, as it reduces the risk of HCC development and lowers the risk of liver-related mortality [48-50]. Aspirin may be beneficial as it reduces systemic inflammation through inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase 2 and diminishes the recruitment of immune cells to the liver [51]. Newer drugs which are now still underdeveloped include glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) agonists and farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonists. Clinical data have indicated that GLP1 agonists may possess potential protection against progression of NASH to HCC [52-54]. FXR indirectly inhibits sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP), de novo lipogenesis, and accumulation of lipid in the liver, through the expression of small protein 1 [55]. Obeticholic acid is the most promising FXR agonist, currently in a phase III clinical trial. It prevents the development of HCC in cholestasis rat models and NASH by preventing fibrotic progression through the activation of intestinal/systemic FXR [56]. Acetyl co-enzyme A carboxylase (ACC) inhibitors may show promising benefit in NASH as well as CHC patients who have achieved SVR, as they inhibit de novo lipogenesis, thus improving steatosis and slowing down the rate of fibrotic progression [57, 58].

Surveillance

Current guidelines recommend surveillance in HCC patients with cirrhosis after SVR as well as the subgroup of patients with advanced fibrosis [59]. However, the cost-effectiveness regarding this approach in patients with advanced fibrosis is still under debate [60]. Obesity, liver steatosis, and T2DM were correlated with increased risk of liver-related mortality, particularly highlighting HCC development after achieving SVR [61, 62]. Future clinical studies that develop clinical scoring systems including those metabolic comorbidities are warranted, to better identify which subsets of patients may benefit from the surveillance.

Strengths and limitations

Our study summarized the novel evidence of an association between the presence of metabolic dysfunction and risk of HCC progression in CHC patients who have achieved SVR. This is the first study to do so, with a limited number of included studies. These data can aid a subset of CHC patients who have achieved SVR to be managed in a different way through additional interventions such as dietary and exercise intervention, pharmacotherapy modifying metabolic properties, as well as thorough but also cost-effective surveillance. However, our study has some limitations. We found significant heterogeneity of the definition of metabolic dysfunction used in the included studies. All the studies were observational, so a potential cause-and-effect relationship could not be determined. These data still need to be confirmed with further interventional studies, incorporating metabolic dysfunction management.