Introduction

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a complex genetic disorder, characterised by neonatal hypotonia, leading to sucking difficulties. Its evolution is characterised during childhood by a delay in psychomotor acquisition, hyperphagia, and weight gain. It is considered as a rare disease, due to a defect in chromosome 15, specifically the 15q11-q13 region. Deletion affecting the paternal chromosome region is the most common anomaly, leading to a loss of function [1].

This genetic anomaly can be isolated or associated with other chromosomal abnormalities, such as in our case. To the best of our knowledge, we report the first case of an association of parental 15q11-q13 region deletion and ring chromosome 18. Ring chromosome 18 syndrome is another rare genetic disorder. It is due to chromosome 18q deletion, which is usually characterised by growth retardation, hypotonia, mental retardation, and other manifestations depending on the point of rupture and therefore on the quantity of lost genetic material [2].

In this paper, we aimed to describe the clinical and biological profile, challenges, and the role of growth hormone (GH) therapy in the first described association of Prader-Willi and ring chromosome 18 syndrome in a child.

Bioethical standards

The endocrine research carried out in the Department of Endocrinology-Diabetology and Nutrition, University of Mohammed First in Oujda is registered in the Research Registry under the number research registry 7745, and under reference number 22/2020, titled Evaluation of the epidemiological diagnostic, therapeutic, and evolution profile of endocrine pathologies, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Mohammed First in Oujda (Morocco).

The parents of the patient provided explicit, written consent for the publication of the case report and for the use of the photographs in the manuscript. This consent has been documented and is available upon request. The patient’s identity has been fully anonymised to ensure confidentiality. This consent has been documented and is available upon request.

The research was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Case report

We report the case of a 9-year-old girl who had a history of neonatal hypotonia with sucking disorder. She was the daughter of a third-degree consanguineous marriage and was the eldest of 3 healthy sisters. She had delayed education and learning difficulties. During early childhood, she exhibited psychomotor retardation. She began to sit at the age of one year and started walking without any support at 2 years old. Additionally, the parents noticed hyperphagia with excessive weight gain.

The diagnosis of Prader-Willi syndrome with ring chromosome 18 was established using CGH ARRAY technique. It showed the absence of expression of paternal chromosome 15 in the 15q11-q13 region, and a karyotype showing a ring chromosome 18 according to the formula: 46. XX (37)/46.XX r(18) (p11.3; q23) (27).

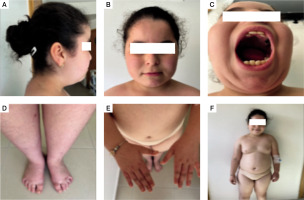

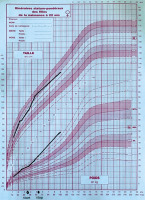

At admission, the first clinical assessment revealed a dysmorphic syndrome: Almond-shaped eyes, acromicria, low implanted hair and ears and overlapping teeth, and thin upper lip (Fig. 1). The patient had a height of 135 cm (+1.4 SD), a weight of 48 kg (+5.3 SD), and grade 2 obesity, with a body mass index of 26.33 kg/m2 (+5.8 SD) (Fig. 2). The patient was in prepubertal in Tanner stage one, with severe hypoplasia of the labia minora and clitoris. Bioelectrical impedance analysis showed 45.4% of body fat and an estimated muscle mass of 51.7%. Bone age was estimated to be around 7 years and 10 months for a corresponding chronological age of 8 years 6 months. The biological evaluation revealed a normal hormonal profile and no abnormalities in the metabolic parameters, and renal and liver function tests (Table I).

Figure 1

Growth chart showing changes in weight, and height before, during and after treatment with growth hormone

Figure 2

The dysmorphic syndrome symptoms observed in our patient: A, B, C) characteristic facial features; D, E) acromicria; F) dysmorphic syndrome

Table I

Results of the blood workup

Clinical and ultrasound cardiac assessment was normal. The abdominopelvic ultrasound showed no abnormalities. The patient also suffered from nocturnal snoring. The polysomnography revealed severe combined sleep apnoea syndrome with an AHI of 31.8/h including hypopnoea (15.8/h) and central apnoea (15.2/h), which will be treated with continuous positive airway pressure. A scoliotic attitude was also noted. Full-spine radiography (frontal and lateral acquisitions) showed a discrete coronal lumbar tilt (L1–L5), with a Cobb angle measured at 2.49°. Consequently, rehabilitation sessions were prescribed. The ophthalmological assessment showed a decrease in visual acuity, so a prescription of corrective eyeglasses was made.

The patient was treated with GH replacement therapy at the age of 3.5 years. The initial dose was 0.035 mg/kg/day, but treatment was stopped at the age of 5 years and 3 months due to financial difficulties [3]. The parents also reported an improvement of their child’s behaviour and learning problems during treatment.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, we have described the first case of a child with associated mosaic ring chromosome 18 and Prader-Willi syndrome. This unique association might be sporadic. The clinical features could also result from these 2 chromosomal abnormalities. These syndromes combine several malformative, metabolic, endocrine, and psychiatric disorders.

Our patient presented with severe neonatal hypotonia, a universal feature, and the first alarming symptom. It is described in both syndromes [1, 4]. She had multiple admissions in a Neonatology Department for sucking and feeding difficulties that improved after initiation of GH treatment. This evolution is in accordance with available data in the literature on mosaic ring chromosome 18 [5]. Later, the patient suffered from hyperphagia and grade II obesity. The pathophysiology of abnormal eating habits in patients with this syndrome is poorly elucidated, manifesting as constant demand for food, uncontrollable hunger, and reduced satiety, which may later be complicated by morbid obesity and type 2 diabetes [1, 6].

Mentally, most children with these 2 syndromes show a degree of variability, ranging from borderline intelligence to severe mental retardation [5, 7]. In the case of ring chromosome 18, it depends on whether the deletion is distal or proximal to 18q [8]. Our patient, who has a more distal deletion, has a moderate degree of cognitive impairment, confirmed by a neurologist using the mini mental state examination. Indeed, some studies have shown severe degrees of mental retardation in patients with proximal deletions of gene 18 and milder forms in patients with distal deletions of 18q [8].

In terms of facial dysmorphism, this patient had a moderate dysmorphic syndrome with almond-shaped eyes, thin upper lip, low hair and ear implantation, overlapping teeth, acromicria, and gonadal hypoplasia. The patient therefore exhibited a dysmorphism made up of a mixture of the 2 syndromes, but predominantly of Prader-Willi syndrome, with a minority of ring chromosome 18, more specifically the deletion of 18q. A particular feature of our patient is the absence of microcephaly, which is a very frequent malformation in ring chromosome 18 deletion. Table II compares the features usually found in both syndromes and the ones found in our patient.

Table II

Clinical comparison between previously reported 18q and 18p deletion syndrome in ring 18 syndrome and our case [1, 3, 11, 16]

Other endocrine disorders frequently associated with hypothalamic-pituitary abnormalities are also part of the clinical picture. Growth retardation due to growth hormone deficiency is often described in ring chromosome 18 syndrome [5]. Our patient was always of average height, and at the age of 3 years and 6 months she benefited from growth hormone treatment. Early initiation of GH therapy in these children is recommended, with the main aim of modifying body composition, improving lipid profile and glucose metabolism, and consequently preventing morbid obesity and its complications, as well as improving cognition in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome at a young age [9, 10]. GH therapy in people with 18q deletions can also increase linear growth and improve their intelligence quotient (IQ) [11]. Our patient’s mother reported a marked improvement in her daughter’s speech, walking, and eating disorders under GH treatment, as well as an improvement in her weight. This finding is in line with the reports that have demonstrated the efficacy GH therapy in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome [6, 9, 12].

Several anomalies overlap between the 2 syndromes (Table II). A higher risk of scoliosis has been described in both syndromes (around 5 times more frequent than in the general population) [1, 4, 13]. Our patient had mild scoliosis that needed several rehabilitation sessions. In terms of sleep quality, there are disturbances to the sleep cycle and/or excessive daytime sleepiness, and nocturnal respiratory disorders with obstructive apnoea even in the absence of obesity [1, 2]. Our patient had severe obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Autoimmune diseases and auditory, cardiac, and cerebral malformations are also very common in ring chromosome 18, but fortunately they were not found in our patient, which eased her prognosis [2, 4, 15].

Prader-Willi syndrome and mosaic ring chromosome 18 also have several endocrine and metabolic abnormalities in common. Despite the presence of these abnormalities in both syndromes, the degree of severity of these disorders has not changed or may even be less intense in our patient compared to previously described case [1, 16, 17]. This observation could be due to the early initiation of GH treatment because we examined the patient after GH therapy discontinuation, or this fortuitous association is simply responsible for a less intense clinical profile and manifestations, taking into consideration the importance of deleted regions of chromosome 18.

To date, there is no specific treatment for both syndromes, only treatments aimed at controlling symptoms and preventing complications, such as GH therapy, balanced nutrition, and physical activity. Obesity in these patients remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality; hence, the importance of preventing it. The diagnosis and management of this complex association require a multidisciplinary approach.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our case contributes to a better understanding of the clinical presentation of complex aberrations of chromosome 18 and that of Prader-Willi syndrome. It was also possible for us to compare endocrine and metabolic parameters in the 2 syndromes. The main common clinical features of this association were a moderate dysmorphic syndrome, hypotonia, grade II obesity with severe OSA, mild cognitive deficit with learning difficulties, and discreet scoliosis. However, statural retardation, autoimmune diseases, and auditory, cardiac, and cerebral malformations are also very common, but fortunately they were not found in our patient, which eased her prognosis.

Diagnosis and management of this complex disorder require a multidisciplinary approach. The primary focus for those patients is to enhance their quality of life and prevent any potential complications. They must be accompanied into society with average abilities in a specific field through special education programs. Controlling their dietary environment is mandatory. Moreover, we believe that the early administration of growth hormone before a definitive prognosis is determined can be beneficial for their overall health and well-being.

POLSKI

POLSKI