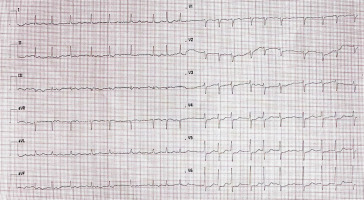

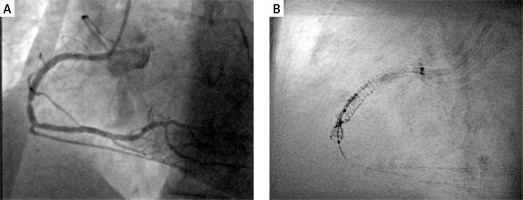

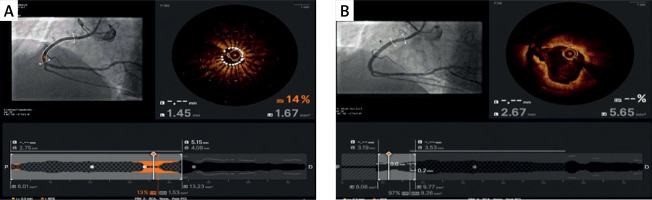

A 75-year-old woman was admitted to the cardiology department for optimization of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within the right coronary artery (RCA). Five days prior, she had been diagnosed with unstable angina and underwent coronary angiography, which confirmed severe coronary stenosis within the RCA. PCI with rotational atherectomy was performed; however, underexpansion of the stent was observed (Figures 1 A, B). Her medical history included arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes mellitus. On admission, she was hemodynamically stable with sinus rhythm on electrocardiogram (Figure 2). She had neither a history of palpitations nor prior documentation of atrial fibrillation (AF). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed preserved left ventricular ejection fraction of 65% with segmental contractility disorders. A hybrid coating guidewire was advanced to the distal part of the RCA using a 6F JR4.0 guiding catheter. Pre-PCI optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirmed underexpansion of the stent with a minimum lumen area of 1.67 mm2 (Figure 3 A). Additionally, significant stenosis was observed in the proximal part of the RCA (Figure 3 B). Given the severe calcific nature of the RCA lesions, the decision was made to use coronary shockwave intravascular lithotripsy (S-IVL). Pre-dilation with a 3.5 × 12 mm non-compliant balloon to 20 atm (Figure 4) facilitated positioning of the S-IVL 2.5 × 12 mm balloon (Shockwave C2+, Shockwave Medical, Santa Clara, CA, USA). A total of 6 cycles of 10 pulses were delivered to the middle and proximal segments of the RCA. Subsequent inflations of a non-compliant balloon 4.0 × 20 mm to 20–26 atm were performed (Figure 5). A drug-eluting stent (4.0 × 18 mm) was implanted in the proximal RCA at 16 atm. The technique resulted in successful treatment of the coronary lesions (Figure 6), confirmed by OCT. A few hours later, the patient reported chest pain and dyspnea. An electrocardiogram revealed AF (Figure 7). Sinus rhythm was restored with amiodarone infusion. After modification of anticoagulant treatment, she was discharged home in good general condition.

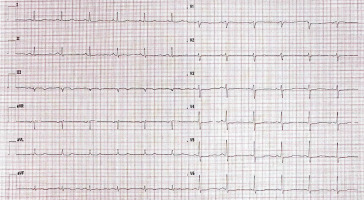

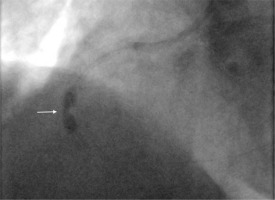

Figure 1

A, B – Coronary angiogram showing underexpansion of the stent in the middle segment of the right coronary artery (RCA, arrows)

Figure 3

Optical coherence tomography showing underexpansion of the stent in the middle segment of the RCA (A) and narrowing in the proximal segment of the RCA (B)

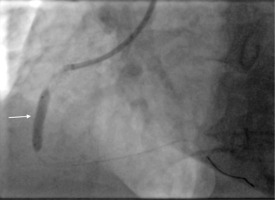

Figure 4

Pre-dilation with a 3.5 × 12 mm compliant balloon within the underexpanded stent with a marked waist caused by a nondilatable calcific lesion (arrow)

Figure 5

Complete non-compliant balloon 4.0 × 20 mm opening within the RCA following shockwave intravascular lithotripsy application (arrow)

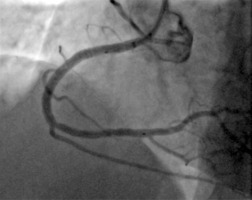

Figure 6

Final coronary angiogram showing successful treatment of the coronary lesions within the RCA

Coronary calcifications encountered during PCI increases the probability of unsuccessful procedures. Heavy calcification may lead to difficulty in catheter transition, problems with balloon dilatation, and suboptimal stent expansion. As a result, it may increase the risk of stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis. Recently, S-IVL has been used to help defragment calcium deposits in coronary arteries and facilitate PCI [1]. The lithotripsy device generates pulsatile mechanical energy that disrupts calcium at the target site, allowing optimal dilation of calcified coronary lesions [1]. However, this energy can trigger cardiac depolarization and arrhythmia [2], as demonstrated in patients undergoing lithotripsy for renal stones [3]. Arrhythmias caused by S-IVL are very rare, with only sporadic case reports confirming both supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias during impulse delivery [2, 4, 5]. In our case, AF appeared several hours after the procedure, suggesting a different arrhythmia mechanism. The delayed AF could be attributed to ischemic damage during PCI or electrolyte disturbances. Nonetheless, physicians should be aware of the risk of cardiac arrhythmias when using S-IVL, including those that may present in a delayed fashion. However, the observed benefits of this technique appear to clearly outweigh these risks.