Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic, progressive inflammatory disorder of the liver with an unknown etiology, characterized by polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia and the presence of circulating autoantibodies [1, 2]. AIH pathomechanisms involve interactions between genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and immune disorders [2, 3]. The estimated incidence of AIH in Europe is 15-25/100,000 population. The disease occurs at all ages, from early childhood to old age, among all ethnic groups, with a significant predominance of women (F : M 3-4 : 1) and with two peaks of incidence: around the age of 20 and between the fourth and sixth decades of life. AIH is clinically and pathologically heterogeneous; hence, diagnostic scales that have been updated over the years are used [1, 3]. Histopathological examination of a liver biopsy is necessary to obtain a diagnosis in the context of comprehensive clinical and serological data. The treatment is long-term immunosuppressive therapy, which in some patients must be continued for life [2, 4].

Liver biopsy and histopathological methodology

Clinical data are necessary for the correct histopathological assessment of liver biopsies due to the similarities in the histopathological picture between many diseases with different etiology and treatment methods [4-7].

The need to perform a liver biopsy in order to diagnose AIH may be a problem among patients with advanced cirrhosis due to the risk of bleeding or significant ascites. Moreover, in cirrhotic patients with advanced fibrosis, the histopathological picture may appear non-specific for AIH. The most important absolute contraindications to biopsy include: lack of patient cooperation, platelet count < 70,000, prothrombin time > 4 s above normal values, use of anticoagulants within 7 days before biopsy and massive ascites. Before performing a liver biopsy, the patient’s blood group, blood count, and blood clotting times (prothrombin time [PT] with international normalized ratio [INR], activated partial thromboplastin time [APTT]) should be determined. Additionally, antiplatelet drugs should be temporarily discontinued 10 days before the biopsy, warfarin should be stopped 5 days before, and heparin should be stopped 24 hours before. After the procedure, antiplatelet drugs are started after 48 hours at the earliest, and warfarin after 24 hours [8]. If there is a high risk of bleeding, a biopsy can be performed via transvenous access, which does not involve damage to the liver capsule, and therefore the risk of bleeding is lower. However, when this method is used, the amount of material collected for testing is often smaller than with the standard procedure. Transvenous biopsy may also be considered in patients with massive ascites or in people with obesity [8, 9]. The most common complications of liver biopsy include pain around the biopsy site, radiating to the diaphragm and right shoulder, and subcapsular and/or interstitial hematomas. Significant hemorrhage, which is the most serious complication, is rarely observed (0.4%). Additionally, pneumothorax, hemothorax or bleeding into the bile ducts may occur [8].

It is important to properly complete the referral form for histopathological examination, providing key clinical data from the interview, symptomatology and serology. It is recommended to use a needle of at least 16 G, as thinner needles are inappropriate and provide material that is too small in diameter. Biopsies should be a minimum length of 1.5 cm, although longer biopsies (> 2.5 cm) provide additional benefits, especially when assessing the degree of fibrosis [6]. A suboptimal biopsy sample may cause diagnostic limitations. A tissue roll containing 10-12 portal areas is considered a representative liver biopsy. For the histopathological evaluation of liver biopsy to be reliable, the content of at least 8 portal spaces is required. This allows for a full assessment of inflammatory activity, fibrosis and architectural relationships between tissue structures [6, 9, 10].

Liver biopsy samples should be immediately fixed in buffered formalin and sent to the pathology department. In the pathology department, the biopsy specimen is described macroscopically, placed in a cassette and subjected to routine histotechnological processes. The paraffin block containing the biopsy specimen is cut on microtome and placed on a glass slide (2-3 sections per slide) and stained using a basic histopathological method, hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining [9]. Additional histochemical methods in each case include connective tissue markers useful for an assessment of the severity and extent of fibrosis, such as Masson or van Gieson, Sirius red, and Gomori staining [6, 7]. Copper staining (rubeanic acid, rhodanine) is used to differentiate AIH from Wilson’s disease and diseases primarily affecting the bile ducts [5], and to distinguish cholestatic from hepatic damage. Other methods used include Perls iron staining, and PAS staining to visualize possible protein deposits. The choice of staining methods depends on the experience and protocols in a given center [6, 7, 11, 12].

The most frequently used immunohistochemical staining in the diagnosis of AIH is CK7, which allows the visualization of cells with biliary differentiation, but staining for plasma cells, such as MUM1, CD138, is also practicized [5, 10].

Histopathological diagnosis should include information on the diagnosticity of the material, as interpretation of the image depends on the amount and integrity of tissue available for assessment [5, 6, 9]. The pathological report of the biopsy specimen should include information about changes in individual structural elements – portal spaces, lobules, sinuses, central veins. It is also necessary to describe the degree of fibrosis – its location, severity and maturity [6]. There is no single, universal system of morphological assessment. Histopathologists most often prefere 3-4 scales for inflammation and fibrosis, including Scheuer, METAVIR, and Ishak scoring systems [5, 7]. When choosing the scale, the guidelines and experience of a given center should be taken into account. The terminology currently recommended in AIH includes the following terms: unlikely, possible, or likely AIH [6]. The interpretation of changes in liver biopsy specimens is also important in assessing the response to treatment and in the diagnosis of changes coexisting with AIH. Additionally, the presence and extent of hepatocyte steatosis and other lesions are taken into account [4-7].

Clinical picture

The clinical picture of AIH is multifaced on physical examination. The course of the disease, usually chronic, may be asymptomatic or mild, which is why some patients are diagnosed in the stage of liver cirrhosis [2, 4]. Most patients (85%) experience fatigue. Other common non-specific long-term symptoms are weakness, abdominal pain, weight loss, nausea, itching, loss of appetite, and polyarthralgia, mainly affecting small joints. Various degrees of jaundice and symptoms of endocrinopathy, e.g., amenorrhea, may occur. In some patients, AIH presents as acute liver damage or failure or exacerbation of chronic, low symptomatic disease [13, 14]. In many patients, no abnormalities are detected in the physical and laboratory examination, despite the presence of active hepatitis in the liver biopsy. In children and adolescents, the course of AIH is more aggressive than in adults and it can be diagnosed in the acute phase. Typically, the activity of a chronic disease fluctuates, with periods of exacerbations and remissions, but also, less often, it may be constant. In untreated patients, decompensated liver cirrhosis develops in over 80% of cases [2]. In Europe, AIH accounts for 2-3% of indications for liver transplantation. AIH may co-occur with other autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto’s disease, type 1 diabetes, Graves’ disease, IBD, celiac disease, psoriasis, RA and other connective tissue diseases [2, 4, 15].

Regardless of the presence and severity of clinical symptoms, laboratory tests in patients with AIH show varying degrees of elevation of liver transaminase activity, with alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) activity predominating. These values may remain slightly above the normal range for a long time, while in the case of acute AIH, ALAT and aspartate aminotransferase (ASPAT) activities may be very high, reaching > 10 times the upper limit of normal. Cholestatic enzyme levels may remain within normal limits or be slightly elevated. In patients with increased alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP) activity, the potential coexistence of other biliary diseases/overlap syndromes should be considered. Hypergammaglobulinemia and/or increased immunoglobulin (Ig)G levels are observed in 85% of patients, rarely accompanied by increased IgM antibodies. Elevated IgM levels should raise the suspicion of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC).

Routinely, the first step in autoantibody diagnostics includes testing for antinuclear (ANA), anti-smooth muscle (ASMA) and anti-liver-kidney microsomal antigen 1 (LKM-1) antibodies [2, 4]. Other non-standard antibodies that may be present include soluble liver antigen (SLA, highly specific for AIH), atypical anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic ANCA antibodies (atypical pANCA), and anti-liver cytosolic antibodies. In an acute phase, the absence of autoantibodies and normal concentrations of gamma globulins and IgG are often observed. In an exacerbation of AIH, which overlaps with a pre-existing chronic liver disease, hypergammaglobulinemia and increased IgG levels are more common, and there are indicators of the chronicity of the process in the liver biopsy [2, 13].

The basic immunological technique for screening is indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) on rat sections (rodent IIF), which enables the detection of ANA, AMA, SMA, LKM-1, LC-1, and AMA antibodies. In clinical practice, only the determination of anti-SLA antibodies requires the use of molecular techniques (ELISA or blot) [15]. It is not recommended to use IIF methods on Hep-2 cells as the first diagnostic method (screening) due to false positive results at low antibody titers. The IIF Hep-2 method is recommended for use as the second stage of immunological diagnostics when the presence of ANA antibodies is confirmed in a significant titer (≥ 1 : 40 adults, ≥ 1 : 20 children). The larger nuclei of Hep-2 cells enable precise determination of the type of antibody fluorescence [15]. The most common types of ANA antibody fluorescence in patients with AIH are homogeneous and speckled. At the same time, in the case of using Hep-2 cells in IIF, it is possible to detect the types of fluorescence characteristic of ANA antibodies specific for PBC: anti-sp100 with the multiple nuclear dots fluorescence type and anti-gp210 antibodies with the rim-like fluorescence type [15, 16]. The detection of anti-SMA antibodies is strongly influenced by the type of fluorescence: vascular and glomerular (VG; arterial wall and glomeruli) and vascular, glomerular, and tubular (VGT; arterial wall, glomeruli and tubuli), which are found almost only in sera of patients with AIH. The V pattern of staining (only arterial walls) anti-SMA antibodies is not specific for AIH and is detectable in a variety of diseases. Table 1 presents basic information on other autoantibodies used in the diagnosis of AIH. There are two basic serological types of AIH. Type 1 AIH, in which ANA and/or SMA autoantibodies are present, affects 90% of cases, and patients usually respond well to the typical treatment. Type 2 AIH, in which LKM-1 antibodies are detected, occurs mainly in younger patients and is characterized by a worse response to treatment [3, 13, 14]. Antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) prevalence is 5.1% of patients with AIH [17]. The presence of AMA antibodies may suggest AIH/PBC overlap syndrome [18, 19].

Table 1

[i] ANA – antinuclear-antibody, AIH – autoimmune hepatitis, IIF – indirect immunofluorescence, SMA – smooth-muscle antibody, LKM – liver kidney microsomal, LC – liver microsomal, SLA – soluble liver antigen, pANCA – peripheral antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, AMA – antimitochondrial antibody, IBD – inflammatory bowel disease, ASC – autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis, PSC – primary sclerosing cholangitis, PBC – primary biliary cholangitis

Table 2

The overall goal of AIH treatment is to achieve both clinical and biochemical remission, where normalization of transaminase activity and IgG level is a laboratory criterion for disease remission. However, this does not mean the remission of the inflammation at the tissue level. An attempt to discontinue treatment can be made after at least 2 years of biochemical remission and confirmation of no signs of active inflammation or only minimal hepatitis in a liver biopsy [4, 15]. In patients without liver cirrhosis, serum transaminases and IgG levels within the normal ranges define complete biochemical remission and are considered laboratory markers of low histological disease activity. Unfortunately, in patients with developed liver cirrhosis, the assessment of histological disease activity based on the assessment of ALT activity and IgG serum concentration is insufficient. Histopathological examination confirmed low disease activity in only about 30% of patients with normal values for both ALT activity and IgG level in blood [20]. In recent years, numerous biomarkers – e.g. adenosine deaminase (ADA), cytokeratin-18 death marker m65, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β1), tumor necrosis factor family B-cell activating factor (BAFF), anti-asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR), forkhead box P3(FOXP3)/retinoid-related orphan receptor gamma t(RORgt) ratio, deoxyribonuclease (DNase 1), ferritin, CD74:macrophage migration inhibitor factor (MIF) ratio, and the vitamin D receptor – have been proposed for the assessment of severity and prognosis at the different stages of AIH (induction therapy, remission, drug-withdrawal, relapse), but further research in this direction with validation studies is necessary [21].

Histopathology and diagnostic scales in AIH

According to the guidelines, a definite diagnosis of AIH cannot be made without performing a liver biopsy [4-8]. Histopathological examination enables the assessment of inflammatory activity and staging, and supports therapeutic decisions. A biopsy should be performed before immunosuppressive treatment is initiated. Pathological examination of the liver biopsy plays an important role in initial diagnosis of AIH, and the termination of immunosuppressive treatment [1, 11, 22-24].

Although there are no pathognomonic morphological features for AIH, there is a set of characteristic lesions indicative of AIH. Typically, chronic active severe portal/periportal and lobular inflammation with destruction of hepatocytes is observed [5].

Characteristics of the inflammatory process in AIH

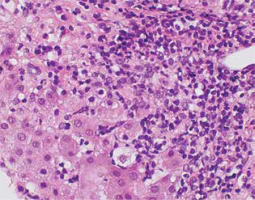

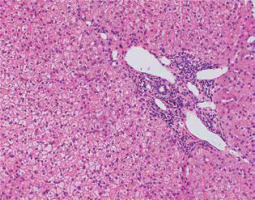

Portal inflammation – the inflammatory infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells, mainly lymphocytes, with an admixture of plasma cells in various amounts. The infiltrate can also contain sparse granulocytes – eosinophils and neutrophils. Plasmacytes are considered typical inflammatory cells for AIH, but their number may vary from be abundant to absent (up to 35% of cases) (Fig. 1) [3, 5]. Plasmacytes forming clusters are highly suggestive of AIH; it is even recommended to count plasma cells [5, 6, 25]. Lymphoplasia with lymphoid nodule formation occurs in AIH, but is not common [6, 7].

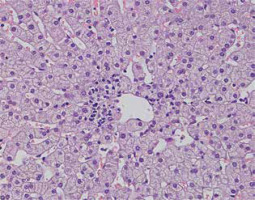

Fig. 1

Active AIH: Intense portal/periportal inflammation with multiple plasmacytes, high lobular activity and degeneration of hepatocytes (HE, 400×). Copyright Prof. Ewa Iżycka-Świeszewska

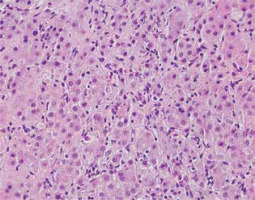

Interface hepatitis – the inflammatory infiltrate crossing the limiting plate, penetrating the lobules with active destruction – is one of the typical features [6, 7]. Usually, intense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate extends into the lobule towards the limiting plate, causing various degrees of periportal hepatocyte necrosis, degeneration and regeneration of hepatocytes, and active proliferation of the connective tissue [5, 7, 19]. The presence of interface hepatitis, even as an isolated feature, can support AIH diagnosis (Fig. 2) [5].

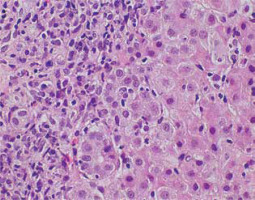

Fig. 2

Active AIH: High lobular inflammation with scattered hepatocyte necrosis (HE, 400×). Copyright Prof. Ewa Iżycka-Świeszewska

Inflammatory lesions within the lobules include an inflammatory-necrotic process, from spotty lesions to diffuse necrosis [22, 26]. Pyknotic changes in hepatocytes, apoptotic bodies and degenerative lesions such as edema and ballooning, as well as loosening of the trabecular structure and sinusoidal inflammation, are common [19, 26]. In some cases, bridging necrosis (portal-portal, portal-central) is found. Pericentral inflammation and necrosis may coexist with the portal/periportal activity. The isolated form without a portal component indicates an early, acute phase of the disease (Figs. 3, 4) [4, 14].

Biliary changes

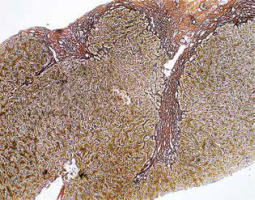

Cholestasis is usually not observed, but mild changes in the bile ducts may be present. Ductal/ductular reaction – an increase in the number of small intrahepatic bile ducts/cholangioles – is a non-specific form of regeneration with bidirectional differentiation of hepatic stem cells, accompanied by increased inflammation and fibrosis (Figs. 5, 6) [5, 7].

Fig. 5

Active AIH: Advanced fibrosis counterstained with Gomori reticulin method (100×). Copyright Prof. Ewa Iżycka-Świeszewska

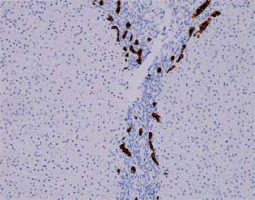

Fig. 6

Active AIH: Ductular reaction accompanying advanced hepatic fibrosis in course of AIH (IHC cytokeratin 7, 200×). Copyright Prof. Ewa Iżycka-Świeszewska

Bile duct injury is observed quite often in AIH, and in some cases the lesions can resemble PBC with varying degrees of severity. This type of lesion should be clinically differentiated from overlap syndromes [18, 19]. Probably, the autoimmune inflammatory reaction also affects the ducts, although destruction (ductopenia) does not occur in the course of AIH [4, 7]. Damage to the bile ducts depends on the intensity of portal inflammation. In the differential diagnosis, immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) is suitable. CK7 expression in periportal hepatocytes indicates chronic cholestasis; however, such an interpretation should be excluded in cases with significant fibrosis, > 2 according to the Batts-Ludwig scale [5, 7].

Other changes

Hepatocytic rosettes (arrangements of cells around spaces with an identifiable lumen) have been previously considered characteristic for AIH, but are now interpreted as a manifestation of non-specific damage and regeneration [5-7].

Emperipolesis is another lesion considered typical of AIH. It means the presence of mononuclear cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells) in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (65-78% of cases). This lesion is currently not considered a specific marker of AIH [5-7, 22].

Giant cell transformation of hepatocytes in adults – postinfantile giant cell hepatitis – indicating degeneration/reaction in various types of hepatitis, is most common in the course of AIH, although it is not a pathognomonic finding [5, 27].

Recently, it has been suggested that the presence of PAS-positive hyaline deposits in Browicz-Kupffer cells, corresponding to Russel bodies, may be specific for AIH and is an additional helpful diagnostic feature [11, 28, 29]. Another feature is the presence of apoptotic lymphocytes in the portal areas, which is a proposed new, quite specific marker of AIH [10].

Autoimmune hepatitis is most often a chronic inflammatory condition (Figs. 7, 8). The acute presentation of AIH may be an exacerbation of subclinical AIH or de novo AIH. It is not possible to clinically distinguish acute AIH from other acute hepatitides, and, paradoxically, there may be no typical abnormalities in the blood serum [5, 13, 15, 29]. In the case of the acute presentation of AIH, centrilobular necrosis may be the only histopathological symptom [11]. Additional criteria supporting AIH in the acute presentation include central perivenulitis, bridging or even panlobular necrosis involving multiple lobules, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with lymphoplasia [29, 30].

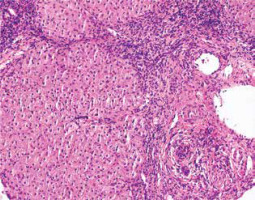

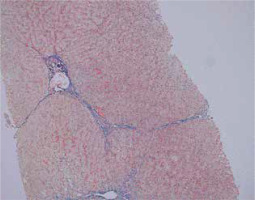

Fig. 7

Remission of AIH: With mild portal lymphocytic reaction (HE, 200×). Copyright Prof. Ewa Iżycka-Świeszewska

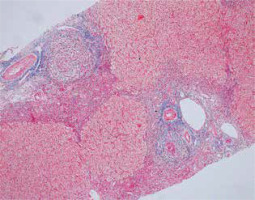

Fig. 8

Remission of AIH: Inactive process but in stage of cirrhosis (Masson, 100×). Copyright Prof. Ewa Iżycka-Świeszewska

Autoimmune hepatitis in the acute phase is diagnosed more often in children and adolescents, and it is mostly type 2 AIH, with a more aggressive morphological picture than usually in adults [4, 15]. No current scoring system is fully appropriate for the juvenile form of the disease, and there is no diagnostic algorithm to differentiate between AIH and autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis (ASC) [4, 30]. ASC is serologically (ANA/SMA+) and histologically similar to AIH-1; therefore it is necessary to perform cholangiography at the time of disease presentation [30, 31]. Another diagnostic problem is posed by the de novo diagnosis of AIH in patients after liver transplantation [3, 31].

Grading and staging

Systems used for grading and staging in hepatitis assess the severity of the disease and the extent of liver injury based on specific criteria and scoring scales and provide important information for clinical management, including the decision on immunosuppressive treatment. These systems rely on the subjective assessment of histological features, and the consistency/reproducibility of the results may vary [5, 12]. In AIH, grading (referring to the extent of inflammatory activity) and staging (the degree of fibrosis) are determined according to various classifications used in chronic viral hepatitis [5, 7].

The classification of inflammatory activity by Scheuer (1991) categorizes inflammatory infiltration in the portal areas as: G0 – absent, G1 – minimal, G2 – occupying < 50% of the portal area, G3 – occupying more than 50% of the portal area and/or around the limiting plate, G4 – intense inflammatory infiltration around the limiting plate, portal-portal inflammatory bridges [32, 33].

The most commonly used classification – Batts-Ludwig (1995) – uses the following scale to assess the activity of portal/periportal inflammation: 0 – none or minimal in the portal areas, 1 – minimal, focal inflammatory infiltrates within the limiting plate, 2 – mild inflammatory infiltrates within the limiting plate in some or all portal areas, 3 – moderate inflammatory infiltrates within the limiting plate in all portal areas, 4 – intense inflammatory infiltrates within the limiting plate with bridging necrosis. Lobular activity is categorized as follows: 0 – no inflammation, 1 – minimal: single foci of necrosis (1-2 dead hepatocytes in the biopsy specimen), 2 – mild: scattered necrotic hepatocytes, 3 – moderate: confluent necrosis (groups of dead hepatocytes), 4 – severe: bridging necrosis [12, 34].

The most frequently used fibrosis scales include those proposed by Scheuer (1998), Metavir (1994), and Ishak (1995). Ishak’s scale is most commonly used, dividing fibrotic process into six stages: 0 points – no fibrosis, 1 point – fibrosis in some portal areas, with or without short septa, 2 points – fibrosis in most portal areas, with or without short septa, 3 points – fibrosis is present in most of the portal areas, with a few portal-portal bridges and short septa, 4 points – portal fibrosis with numerous portal-portal and portal-central bridges, 5 points – numerous portal-portal and portal-central bridges with a few regenerative nodules (incomplete cirrhosis), 6 points – complete nodular transformation [12, 32-34] (Figs. 5, 6).

Clinicopathological diagnostic scales for AIH

In 1993, the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) developed a diagnostic scale, which was revised in 1999 and then simplified in 2008 [1, 3]. Currently, the most frequently used criteria are the 2008 IAIHG, classifying AIH as definite, probable or unlikely. In this system, a score of 6 points means probable and 7-8 points is definite AIH. Histopathologically, according to this scale, there is a typical image for AIH (inflammation within the limiting plate with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates penetrating the lobules, emperipolesis and rosettes) – 2 points, an image corresponding to AIH – 1 point, and an image atypical of AIH – 0 points [22, 30]. One point is given when the ANA or SMA antibody titer ≥ 1 : 40, 2 points when the ANA or SMA antibody titer ≥ 1 : 80, or the anti-LKM1 antibody titer ≥ 1 : 40, or anti-SLA/LP is positive. IgG levels are also tested, with 1 point being given when they exceed the upper normal level (16 g/l), 2 points when the upper normal level is exceeded by more than 1.1 times. After summing up all the points, AIH can be described as probable (6 points) or definite (7-8 points).

In recent years, it has been found that some elements of the histopathological assessment are not reflected in practice, and the criteria are not adequate in acute AIH, overlap syndromes and AIH coexisting with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [6, 11, 15, 29].

In 2017, Balitzer et al. proposed new criteria for the simplified IAIHG system in order to increase diagnostic sensitivity (Table 3) [7]. They modified criteria of the activity of hepatitis, number of plasma cells and presence/absence of biliary features. To assess the damage to the bile ducts, they suggested staining for copper and CK7, as negative CK7 and copper staining with biliary features support AIH. Inflammatory activity was graded according to the modified Ishak scale (mHAI), where category A refers to periportal or periseptal interface hepatitis, B refers to diffuse necrosis, and C describes focal, spotty necrosis, apoptosis and inflammation. Category D refers to portal inflammation [7, 33].

Table 3

Proposed criteria for scoring histopathological changes (according to Balitzer et al., 2017); *when no bridging fibrosis is present, ** 1 and 2 necessary to assign 1 point, except acute presentation

Balitzer et al. used the following scale to count plasma cells: none, few (< 2), medium number (2-4), abundant (> 5) within the lobular or portal area. Moreover, they considered > 5 plasma cells in one visual field to be a cluster pathognomonic for AIH. The analysis also showed that emperipolesis and rosettes, previously considered to be characteristic criteria for AIH, are a non-specific marker of the severity of inflammation and renewal processes. They are highly specific but not very sensitive, and the use of these criteria leads to underdiagnosis in many cases of AIH [7, 29].

The latest update of histopathological guidelines is the 2022 Consensus of the European Reference Network for Hepatological Diseases, International AIH Pathology Group and ECP. [6]. A team of experts analyzed the standards, diagnostic criteria and grading of AIH with acute and chronic presentation. Recommendations were developed regarding the minimum requirements for establishing the diagnosis, terminology for the probability of AIH diagnosis, histological criteria and scales for assessing disease activity and progression. The criteria are presented in Table 4. The 2022 consensus’ terminology is divided into: AIH unlikely, AIH possible, AIH likely. Inflammatory activity was graded according to the modified Ishak scale (mHAI), while the authors pointed out that other classifications can also be used [6].

Table 4

Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune hepatitis in the course of both lobular and periportal hepatitis (Lohse et al.) [6]

According to the above guidelines, periportal infiltrate indicates probable AIH if:

it is accompanied by mild or severe lobular infiltration and no changes typical of other liver diseases are present;

there is no lobular infiltration, but also no differentiating symptoms;

if the lobular infiltration is accompanied by changes indicating other inflammatory liver diseases, AIH cannot be ruled out anyway.

Periportal infiltration should be moderate, with centrilobular necrosis and:

lymphocytic infiltration, or

interface hepatitis – inflammatory infiltrate on the border of the lobule and zone 3,

fibrosis in the portal areas, or

no other possible causes.

The differential diagnosis of AIH includes viral hepatitis (acute viral hepatitis A-E, chronic viral hepatitis B and C), alcoholic liver disease (AFLD) and NAFLD, as well as other autoimmune diseases of the liver and biliary tract: primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), IgG4-related cholangitis, and so-called overlap syndromes, e.g. overlap syndrome AIH + PBC/PSC/viral hepatitis. Metabolic diseases such as hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, α1-antitrypsin deficiency and drug-induced/toxic liver injury should also be taken into account [4, 5, 10, 18].

Below, the problems of differentiating AIH from DILI and overlap syndromes are highlighted.

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI)

The differential diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury and drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis (DIAIH) is difficult, both at the clinical and histological level [30, 31]. The drugs most frequently inducing AIH are minocycline and nitrofurantoin, but theoretically any drug can trigger an autoimmune reaction [2, 30, 31]. A thorough medical interview plays a key role in the differential diagnosis. Monitoring the response after glucocorticoid therapy (GCS) is also helpful. In both DILI and DIAIH, improvement is usually observed after glucocorticoids, but in DIAIH, after reducing the dose of the drug in the following months, the disease often relapses [2]. The histopathological picture is very similar, as are the antibodies presented. The absence of cholestasis and the presence of fibrosis will indicate DIAIH, and the absence of advanced fibrosis suggests DILI [2, 5, 35, 36].

Overlap syndromes

Autoimmune hepatitis and PBC overlap syndrome tends to affect adult patients. The diagnosis is based on the presence of typical serological markers and symptoms of both AIH and PBC in biopsy: periportal inflammation, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates in the portal areas, lymphoplasia, granulomas and florid duct lesions [4, 5, 18].

Autoimmune hepatitis and PSC overlap syndrome mainly affects children, adolescents and young adults. It is a syndrome characterized by cholangiographic and histological features typical of PSC: periductal concentric fibrosis and portal lymphocytic infiltration, along with severe features of AIH, simultaneously or subsequently (Figs. 9, 10) [4, 18, 19]. PSC is strongly associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and the incidence of IBD in patients with AIH-PSC overlap is higher than in patients with AIH alone and is consistent with the incidence in isolated PSC. Sclerosing cholangitis in developmental age is often referred to as PSC, according to the adult terminology, but there are differences between PSC and juvenile autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis (ASC) [4, 31]. The term “primary” refers to an undetermined pathogenesis, while in pediatrics there are defined forms of sclerosing cholangitis, such as biliary atresia and autosomal recessive neonatal sclerosing cholangitis. Other congenital conditions include defects in the ABCB4 (MDR3) gene, causing small duct sclerosing cholangitis in children and adults. Sclerosing cholangitis may also be a complication of various diseases – primary and secondary immunodeficiencies, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, psoriasis, cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia [18, 19, 31]. The overlap syndrome of AIH and ASC in children is included in the terminology as a separate disease [30].

Conclusions

Interpretation of liver biopsy images, especially in cases of suspected AIH, requires close correlation with clinical data and constant communication between the hepatologist and pathologist. The use of current diagnostic guidelines makes it possible to objectify the morphological assessment and improve diagnostic accuracy for autoimmune hepatitis and related pathologies. However, further research is needed to identify convenient and accurate biomarkers of AIH to determine the most optimal method and time of treatment.