Introduction

Cardiac tamponade is a pericardial syndrome characterized by diastolic impairment due to the accumulation of pericardial fluid under pressure [1]. Clinical signs of cardiac tamponade (CT) include tachycardia, hypotension, pulsus paradoxus, raised jugular venous pressure, muffled heart sounds, and decreased electrocardiographic voltage with electrical alternans. The occurrence of hemodynamic abnormalities and clinical symptoms depends on the rate of fluid accumulation relative to pericardial stretch and the effectiveness of compensatory mechanisms [2]. CT may be an acute life-threatening condition (e.g. CT by hemopericardium), or may present as a subacute condition allowing in some cases delayed treatment. The causes of cardiac tamponade are various: iatrogenic factors, postpericardiotomy syndrome, malignancies, uremia, heart rupture as complication in case of myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, hypothyroidism, idiopathic linked to inflammatory or immune processes, drug side effects etc. [1, 3, 4].

In a patient with clinical suspicion of cardiac tamponade, ECG and echocardiography are primary tools for CT diagnosis, and to a lesser extent computed tomography. The treatment of CT involves usually drainage of the pericardial fluid, preferably by needle pericardiocentesis (PCC) or a surgical approach [4].

Aim

Studies on the etiology of CT are scarce and usually include selected groups of patients. The aim of this study was to analyze all etiologies of CT in patients treated in the tertiary hospital with cardiology, cardiac surgery and intensive care departments. Additionally, for each group of main etiologies we determined the basic characteristics, in-hospital management, in-hospital and up to 2-year mortality.

Material and methods

The study was carried out in the Silesian Centre for Heart Diseases (SCCS) in Zabrze, Poland, which is tertiary clinical hospital having cardiac surgery, two cardiology and two intensive cardiology care departments. We analyzed retrospectively hospital databases and medical records of all patients older than 18 years with clinical and echocardiographic signs of cardiac tamponade who required pericardiocentesis or pericardiotomy treatment, between January 2008 and December 2018. Five patients with diagnosed CT requiring only conservative treatment as well as all patients whose medical history was not available or were lost to follow-up were excluded. For each of 340 enrolled patients with CT, we established the final etiological diagnoses based on the clinical history, serum biomarkers, pericardial fluid culture, cytology and biochemistry analysis, results of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, as well as pericardial biopsy, if available. For each group with more than 5 patients, the baseline characteristics, length of hospital stay, in-hospital management and long term follow-up were analyzed.

Iatrogenic etiology was divided upon early onset (up to 48 hours after invasive cardiac (IC) or cardiac surgery procedure (iatrogenic cardiac surgery – ICS)) or late onset (> 7 days), which was considered as a separate postpericardiotomy syndrome group (PCT). The invasive cardiac procedures concerning iatrogenic CT performed in our center were: atrial fibrillation ablation, percutaneous coronary intervention, cardiovascular implantable electronic device, temporary pacing electrode, left atrial appendage closure, transcatheter aortic valve implantation and endomyocardial biopsy.

Neoplastic etiology of CT was assigned in case of neoplastic cells in pericardial fluid or presence of concomitant malignant disease. All patients with diagnosed CT caused by connective tissue diseases, infectious or non-infectious pericarditis were assigned to the inflammatory exudative pericarditis group. Uremic CT was established in patients with end stage renal failure in dialysis or predialysis in which other causes were excluded.

Data on long-term follow-up/mortality for all patients were obtained from the Silesian Cardiovascular Base formed as a result of an agreement between the 3rd Department of Cardiology, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Zabrze, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, the SCCS and the Regional-Silesian Branch of the National Health Fund in Katowice.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of continuous variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. None of the variables had a normal distribution. Continuous variables were presented in the form of median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as percentages. In-hospital and post-discharge mortality was presented as the all-cause crude death rate since hospital admission. Statistica 13.1 from TIBCO Inc. and Microsoft Excel were used for statistical and graphic data processing.

Results

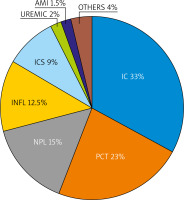

Over an 11-year period 340 patients with CT were diagnosed and treated in our cardiac center, of whom 56% were men. The total median hospital stay was 10 [14] days. Among particular etiologies 8 main subgroups were identified and 7 (beside OTHER group) were further analyzed: iatrogenic group after invasive cardiac procedures, iatrogenic after cardiac surgery procedures, postpericardiotomy syndrome group, neoplastic (NPL), inflammatory (INFL), uremic (UREMIC), acute myocardial infarction complication (AMI) group. In the group of OTHER (n = 13) the following etiologies were included: aortic dissection (4 patients), right sided heart failure with restriction (2 patients), postmyocardial infarction syndrome (1 patient), postradiation (1 patient), trauma with chest perforation (1 patient), coagulation abnormality (1 patient), unknown etiology (3 patients). The proportion of particular groups of etiologies are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Particular groups of etiologies of 340 cardiac tamponades diagnosed and treated between January 2008 and December 2018

AMI – acute myocardial infarction complication, IC – iatrogenic after invasive cardiac procedures, ICS – iatrogenic after cardiac surgery procedures, PCT – postpericardiotomy syndrome, NPL – neoplastic, INFL – inflammatory.

In our study cohort the highest median values of age 74 (20) and 70 (16.6) were found in AMI and IC groups respectively. The lowest median values of age 57–58 were reported in NPL, INFL and PCT groups. The longest hospital stay was typical for the ICS group, 25 (13) days, and 16 (17) days for the INFL group, in contrast to 6 (8) days for NPL and 6 (5) days in the PCT group. Women were in a majority in the NPL (66%) and IC group (52%). Median APTT ratio (coagulation time of test-to-reference plasma) values (normal range: 26–40 s) were high in the UREMIC group, 42.1 s (12.6). High median prothrombic time and international normalized ratio were found in the PCT group (22.5 s and 1.99 respectively). At hospital admission, anemia was present in PCT patients and the sign of renal impairment renal impairment with the lowest glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was especially found in UREMIC and AMI groups. The AMI patients were additionally burdened with leukocytosis. The UREMIC, PCT and both IC and ICS groups were the most disease burdened groups of patients. All baseline characteristics, laboratory parameters and data on comorbidities are summarized in Table I.

Table I

Baseline characteristics, disease burden and laboratory parameters of patients with different etiologies of cardiac tamponade hospitalized between January 2008 and December 2018

[i] AMI – acute myocardial infarction, NPL – neoplasm, IC – iatrogenic after invasive cardiac procedures, ICS – iatrogenic after cardiosurgery procedures, PCT – postpericardiotomy syndrome, AF – atrial fibrillation, APTT – activated partial thromboplastin time, CAD – coronary artery disease, CHF – chronic heart failure, CKD – chronic kidney disease, CS – cardiac surgery, GFR – glomerular filtration rate, HCT – hematocrit, HGB hemoglobin, INR – international normalized ratio, CREAT – creatinine, MI – myocardial infarction, PAD – peripheral artery disease, PLT – platelets, PT – prothrombin time, RBC – red blood cells, WBC – white blood cells.

The majority of pericardial fluid drainages were performed by pericardiocentesis (PCC); however, 52% of patients from the ICS group underwent PCC and 48% of them required surgery (Table II). Three of 50 patients and 3 of 43 patients from NPL and INFL groups respectively required fenestration of the pericardial sac. The highest total volume of pericardial fluid was drained after AMI (median of 1500 (1900) ml), UREMIC (1140 (500) ml) and NPL (910 (710) ml) etiologies of CT. The lowest volumes of fluid were drained in the IC group (median of 390 (460) ml).

Table II

In-hospital management of patients with different etiologies of cardiac tamponade hospitalized between January 2008 and December 2018

[i] AMI – acute myocardial infarction complication, IC – iatrogenic after invasive cardiac procedures, ICS – iatrogenic after cardiosurgery procedures, MVS – mechanical ventilation support, NPL – neoplasm, PCT – postpericardiotomy syndrome, inotropes – sympathomimetic amine therapy, PCC – pericardiocentesis.

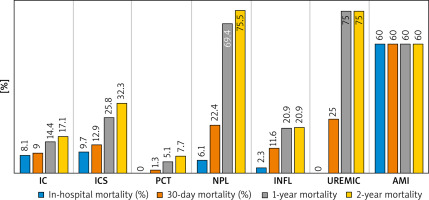

Inotropes together with mechanical ventilation support were used in a high percentage in AMI patients (80%, 60% respectively), then in ICS (29%, 13% respectively) and IC patients (28%, 15% respectively). The lowest frequency of such treatment was required in the PCT group. The type of treatment and in-hospital management data for all etiologies are summarized in Table II. In-hospital, annual and 2-year mortality rates for different etiology groups are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2

In-hospital, 30-day, 1-year and 2-year mortality for different etiology groups of patients with cardiac tamponade, hospitalized between January 2008 and December 2018. In-hospital and post-discharge mortality is presented as all-cause crude death rate since hospital admission. For that reason, 30-day, 1-year and 2-year mortality in AMI group remained high

AMI – acute myocardial infarction, CT – cardiac tamponade, NPL – neoplasm, IC – iatrogenic after invasive cardiac procedures, ICS – iatrogenic after cardiac surgery procedures, INFL – inflammatory, PCT – postpericardiotomy syndrome.

Discussion

We present the largest contemporary study on CT assessing 340 consecutive patients diagnosed and treated for CT over an 11-year period. Before the era of percutaneous invasive cardiac procedures, malignancy (primarily lung and breast cancer) was the leading cause of CT [5, 6]. Our series from a tertiary care cardiology hospital confirms the iatrogenic cause as the predominant one (42%) and our observations are in line with a recent study by Orbach et al. [7].

Iatrogenic CT is a rare but life-threatening complication [8]. The risk of iatrogenic CT or pericardial effusion increases with the need for transseptal puncture and intraprocedural anticoagulation [9]. In our study, among 340 included patients, 112 (33%) after IC procedures and 31 (9%) after ICS procedures were identified. In the group of IC the lowest total pericardial volume was drained. It shows that iatrogenic CT is more likely to develop rapidly with coexistence of relatively small pericardial hemorrhages. In 82% of IC patients PCC was used as a successful emergency treatment, and 18% required thoracotomy. After the AMI group, IC as well as ICS patients had the highest need for advanced treatment and higher in-hospital mortality among all studied patients. However, overall mortality up to 2 years was definitely superior in the ICS group in comparison to CTs after IC procedures (Figure 2). Additionally, ICS patients had the longest hospital stay among all analyzed groups (median: 25 days) and 42% required reoperation. The data on drained volumes are not satisfactory in the ICS group, mostly because of the urgent need for surgical decompression and the lack of such information in patients’ histories.

The study results concerning CT after defined percutaneous invasive cardiac procedures performed in our clinical center between 2006 and 2018 have been recently published [10].

The postpericardiotomy syndrome occurs mostly 1 to 6 weeks after cardiac surgery, but clinical symptoms may occur as late as several weeks to months after surgery and may be associated with significant morbidity. It is believed that PCT results from a heightened immune response to injury following cardiothoracic surgery [11, 12]. Incidence of PCT is close to 10% but varies among studies from 2% to 30%, as well as according to type of cardiac surgery performed [13]. Although most patients have an uncomplicated clinical course with good prognosis after standard pharmacological treatment, some studies report cases of patients with late diagnosis that required pericardial drainage or even redo surgery [11]. In our study cohort, PCT syndrome was the second most frequent etiology of the CT (78 of 340), although with the shortest hospital stay, the lowest need for advanced therapy and with the best prognosis.

In our 340 consecutive patients 50 (15%) of them were assigned to the NPL group. Cardiac tamponade in case of the NPL process was present in 50/96 (52%) in a study by Navarette et al. [5], 74/114 (65%) by Cornily et al. [14] and 43/136 (32%) by Sánchez-Enrique et al. [6]. In-hospital stay for the NPL group was short, mostly because of patients being referred to our center for diagnostic and therapeutic PCC. In only 2% of them pericardiotomy was additionally performed as PCC was not satisfactory. Only 6% of them required advanced treatment. Although the in-hospital mortality was not high, the annual and 2-year mortality was significant, reaching 2-year mortality of up to 75%. Nevertheless, such high mortality may be consequence of primary disease, not CT alone.

In our analysis, all causes, infectious or noninfectious, as well as collagen disease inflammatory exudative pericarditis, were united together in the INFL group. The purpose was to define a bigger group to obtain reliable statistical results. The INFL group consisted of 43 (12.5%) patients, 6 with a diagnosis of viral, 6 of bacterial (2 tuberculosis), 6 of collagen disease, 1 toxoplasmosis and 25 of unknown inflammatory etiology. Most previous publications focused on individual and different inflammatory etiologies, so the nomenclature, in our opinion, is not consistent. INFL was one of the youngest groups, with mean age of 57.5 (26), with the second longest median hospital stay. Concerning in-hospital management and long-term mortality, this group was in the middle position among all groups.

Uremic pericarditis typically occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease [15]. Cardiac tamponade, a further complication of uremic pericarditis, is more common in dialyzed than in non-dialyzed patients with chronic renal failure, and must be in most cases treated by pericardiocentesis [16]. Some studies defined the number of uremic CTs as 12 of 96 patients (12.5 %) [5] or 11/50 (20%) [17]. Our UREMIC group consisted of 8 patients with end-stage renal disease, of whom 70% were men. It was the group of patients with the highest percent of co-morbidities, and although in-hospital mortality was 0%, annual and 2-year mortality was equal to the NPL group. Such high mortality may be a consequence of primary disease, not CT alone.

Cardiac tamponade during myocardial infarction is mainly due to heart rupture, or more rarely to hemorrhagic evolution of post-myocardial infarction pericarditis [1]. In our analysis there were only 8 patients with CT as a complication of myocardial infarction. Such a small number of wall perforations during AMI is most likely due to the implementation of more precise diagnostic methods and more effective treatments, including invasive interventions [18]. It was group with the highest total volume of drained pericardial fluid, the highest percentage of required intensive care therapy (80% of patients with inotropes and 60% with mechanical ventilatory support) and the highest in-hospital mortality of about 60%. It may be obviously explained mostly by rupture of the heart and massive hemorrhage.

Conclusions

Most CTs are observed after invasive cardiac procedures, following by postpericardiotomy syndrome, neoplasm, cardiac surgery procedures, inflammatory, uremic and acute myocardial infarction complications. Pericardiocentesis was used as successful first-line emergency treatment in the majority of cases. The worst in-hospital prognosis was noted for CT following acute myocardial infarction complications and both invasive cardiac and cardiac surgery iatrogenic CTs. The highest annual and 2-year mortality was recorded for UREMIC and NPL groups, which is most likely the result of the underlying disease.